AVAILABLE from Jamaica Plains, MA 02130

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Passamaquoddy, They Speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (Also Known As Maliseet- Passamaquoddy

1.1 Passamaquoddy, they speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also known as Maliseet- Passamaquoddy. It is an endangered language from the Algonquian language family (1) 1.2 Pqm (2) 1.3 45.3,-66.656 (3) 1.4 The Passamaquoddy tribe belonged to the loose confederation of eastern American Indians known as the Wabanaki Alliance, together with the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes. Today most Passamaquoddy people live in Maine, in two communities along the Passamaquoddy Bay that bears their name. However, there is also a band of a few hundred Passamaquoddy people in New Brunswick. The French referred to both the Passamaquoddy and their Maliseet kinfolk by the same name, "Etchimins." They were closely related peoples who shared a common language, but the two tribes have always considered themselves politically independent. Smallpox and other European diseases took a heavy toll on the Passamaquoddy tribe, which was reduced from at least 20,000 people to no more than 4000. Pressured by European and Iroquois aggression, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy banded together with their neighbors the Abenakis, Penobscots, and Micmacs into the short-lived but formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. This confederacy was no more than a loose alliance, however, and neither the Maliseet nor the Passamaquoddy nation ever gave up their sovereignty. Today the Passamaquoddy live primarily in the United States and the Maliseet in Canada, but the distinction between the two is not imposed by those governments--the two tribes have always been politically distinct entities. (4) 1.5 After working with the French and joining the Abnaki confederation against the English, many converted to Catholicism. -

A Report on Indian Township Passamaquoddy Tribal Lands In

A REPORT ON INDIAN TOWNSHIP PASSAMAQUODDY TRIBAL LANDS IN THE VICINITY OF PRINCETON, MAINE Anthony J. Kaliss 1971 Introduction to 1971 Printing Over two years have passed since I completed the research work for this report and during those years first one thing and ttan another prevented its final completion and printing. The main credit for the final preparation and printing goes to the Division of Indian Services of the Catholic Diocese of Portland and the American Civil Liberities Union of Maine. The Dioscese provided general assistance from its office staff headed by Louis Doyle and particular thanks is due to Erline Paul of Indian Island who did a really excellent job of typing more than 50 stencils of title abstracts, by their nature a real nuisance to type. The American Civil Liberities Union contrib uted greatly by undertaking to print the report Xtfhich will come to some 130 pages. Finally another excellent typist must be thanked and that is Edward Hinckley former Commissioner of Indian Affairs who also did up some 50 stencils It is my feeling that this report is more timely than ever. The Indian land problems have still not been resolved, but more and more concern is being expressed by Indians and non-Indians that something be done. Hopefully the appearance of this report at this time will help lead to some definite action whether in or out of the courts. Further research on Indian lands and trust funds remains to be done. The material, I believe, is available and it is my hope that this report will stimulate someone to undertake the necessary work. -

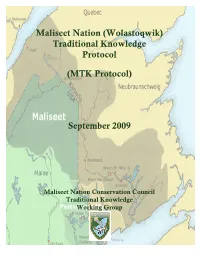

Traditional Knowledge Protocol

Maliseet Nation (Wolastoqwik) Traditional Knowledge Protocol (MTK Protocol) September 2009 Maliseet Nation Conservation Council Traditional Knowledge Working Group Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… i 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 2.0 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 2 3.0 Interpretation ………………………………………………………………… 3 4.0 MTK Methodology …………………………………………………………… 4 I Project Planning ………………………………………………………… 5 II Delivery and Implementation ……………………………………………… 6 III Finalizing Report and Disclosure ………………………………………… 7 5.0 Amendments …………………………………………………………………… 7 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………… 8 Maliseet Leadership Proclamation / Resolution …………………………… 9 Draft Maliseet Ethics Guidelines ……………………………………… 10 Foreword Development of the Maliseet Nation Traditional Knowledge (MTK) Protocol highlights the recognition of the importance of Aboriginal traditional knowledge in relation to the environmental issues facing Maliseet traditional territory, the Saint John River (Wolustok) watershed1. The protection of such knowledge has been identified by the Maliseet Chiefs as a crucial component for future relations with non-Aboriginals, as increasing development activity continues to cause concern for all parties on the best way to proceed, in the spirit of cooperation and with due respect for Maliseet Aboriginal and Treaty rights2. The protocol also addresses past problems with research projects such as lack of consultation of Maliseet people, lack of meaningful community involvement, lack of benefit from research, lack of informed consent, lack of community ownership of data (including analysis, interpretation, recording or access), and lack of respect of our culture and beliefs by outside researchers. Initiated by the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and produced through the combined efforts of informed Maliseet Elders, leaders, committees and grassroots volunteers, this protocol identifies the methods developed by the Maliseet Nation for the proper and thorough collection and use of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). -

A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1977 A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians Susan M. Stevens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revised 1/77 A BRIEF HISTORY Pamp 4401 of the c.l PASSAMAQUODDY INDIANS By Susan M. Stevens - 1972 The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine are located today on two State Reservations about 50 miles apart. One is on Passamaquoddy Bay, near Eastport (Pleasant Point Reservation); the other is near Princeton, Maine in a woods and lake region (Indian Township Reservation). Populations vary with seasonal jobs, but Pleasant Point averages about 400-450 residents and Indian Township averages about 300- 350 residents. If all known Passamaquoddies both on and off the reservations were counted, they would number around 1300. The Passamaquoddy speak a language of the larger Algonkian stock, known as Passamaquoddy-Malecite. The Malecite of New Brunswick are their close relatives and speak a slightly different dialect. The Micmacs in Nova Scotia speak the next most related language, but the difference is great enough to cause difficulty in understanding. The Passamaquoddy were members at one time of the Wabanaki (or Abnaki) Confederacy, which included most of Maine, New Hampshire, and Maritime Indians. -

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations February 2017 Nicole Friederichs Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro Kate Bertino Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Contact Information: 120 Tremont Street Nicole Friederichs Boston, MA 02108 Practitioner-in-Residence Tel.: 1-617-305-1682 Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic Fax: 1-617-573-8100 Suffolk University Law School Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC) is honored to offer this thorough review of the crafting of the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721-1735. In June of 2014, the MITSC completed the Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine where the MITSC offered the following framework: The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, (MICSA), was passed in October of the same year [1980]. The MICSA gave federal permission for the [state Maine Implementing Act] (MIA) to take effect while retaining intact the federal trust relationship between the federally recognized tribes of Maine and the US Congress; and placed constraints on the implementation of the MIA. Of particular interest to the inquiry into the saltwater fishery conflict between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the State of Maine are the following provisions of the federal act: 1. MICSA (25 U.S.C. § 1735 (a)) provides that “In the event a conflict of interpretation between the provisions of the Maine Implementing Act and this Act should emerge, the provisions of this Act shall govern.” The provisions of the federal MICSA thus override the MIA provisions when there is a conflict between the two. -

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story Written by Cindy Blackstock Illustrated by Amanda Strong Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N) zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee- chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc -

Aboriginal Place Names Rimouski: (Quebec) This Is a Word of Mi’Kmaq Or Contribute to a Rich Tapestry

Pamphlet # 24 Ontario: This Huron name, first applied to the lake, the Chipewyan people, and means "pointed skins," a may be a corruption of onitariio, meaning "beautiful Cree reference to the way the Chipewyan prepared lake," or kanadario, which translates as "sparkling" or beaver pelts. Aboriginal Peoples Contributions to "beautiful" water. Place Names in Canada Medicine Hat: (Alberta) This is a translation of the Quebec: Aboriginal peoples first used the name Blackfoot word, saamis, meaning "headdress of a 1 Provinces and Territories "kebek" for the region around Québec City. It refers medicine man." According to one explanation, the to the Algonquin word for "narrow passage" or word describes a fight between the Cree and The map of Canada is a rich tapestry of place names "strait" to indicate the narrowing of the river at Cape Blackfoot, when a Cree medicine man lost his which reflect the diverse history and heritage of our Diamond. plumed hat in the river. nation. Many of the country's earliest place names draw on Aboriginal sources. Before the arrival of Yukon: This name belonged originally to the Yukon Wetaskiwin: (Alberta) This is an adaptation of the Europeans, First Nations and Inuit peoples gave river and is from a Loucheux (Dene) word, LoYu- Cree word wi-ta-ski-oo cha-ka-tin-ow, which can be names to places throughout the country to identify kun-ah, meaning "great river." translated as "place of peace" or "hill of peace." the land they knew so well and with which they had strong spiritual connections. For centuries, these Nunavut: This is the name of Canada's newest Saskatoon: (Saskatchewan) The name comes from names that described the natural features of the land, territory which came into being on April 1, 1999. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work. -

The Wealth of First Nations

The Wealth of First Nations Tom Flanagan Fraser Institute 2019 Copyright ©2019 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief passages quoted in critical articles and reviews. The author of this book has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, there- fore, his own and and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Board of Directors, its donors and supporters, or its staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data The Wealth of First Nations / by Tom Flanagan Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-88975-533-8. Fraser Institute ◆ fraserinstitute.org Contents Preface / v introduction —Making and Taking / 3 Part ONE—making chapter one —The Community Well-Being Index / 9 chapter two —Governance / 19 chapter three —Property / 29 chapter four —Economics / 37 chapter five —Wrapping It Up / 45 chapter six —A Case Study—The Fort McKay First Nation / 57 Part two—taking chapter seven —Government Spending / 75 chapter eight —Specific Claims—Money / 93 chapter nine —Treaty Land Entitlement / 107 chapter ten —The Duty to Consult / 117 chapter eleven —Resource Revenue Sharing / 131 conclusion —Transfers and Off Ramps / 139 References / 143 about the author / 161 acknowledgments / 162 Publishing information / 163 Purpose, funding, & independence / 164 About the Fraser Institute / 165 Peer review / 166 Editorial Advisory Board / 167 fraserinstitute.org ◆ Fraser Institute Preface The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau elected in 2015 is attempting massive policy innovations in Indigenous affairs. -

The Wabanaki Indian Collection

The Wabanaki Indian Collection Compiled by Mary B. Davis This collection contains items from the Passamaquoddy Indian Papers,#9014 and the Abenaki Language Collection, #9045 Contents … Preface … The Wabanakis, by Nicholas N. Smith … Guide to the Microfilm Text Preface The Passamaquoddy Papers, the Joseph Laurent Abenaki Language Collection, and the Micmac Manuscript comprise the Library's Wabanaki Collection. Dated documents range from 1778 to 1913; much of the material is undated. The condition of all three components of the collection is generally poor. The Passamaquoddy Papers, which document the political life for members of that nation during the 19th century, contain many fragments and partial documents impossible to put into proper context in this collection. Using information from other sources, scholars may be able to identify these materials in the future. The Abenaki Language Collection consists of bound manuscripts (and one unbound document) in the Abenaki language which largely pertain to Roman Catholic religious services. They were obtained from the Laurent family, prominent in Abenaki affairs in Odanak, Quebec, after they had sustained a fire. Many of the hand-written volumes are partially charred, resulting in losses of text which will never be retrieved. The Micmac Manuscript is written in the syllabary (sometimes called hieroglyphics) developed by Father Chretian Le Clerq in the 17th century to aid in teaching prayers to Canadian Indians. The Reverend Christian Kauder later used these same characters in his Micmac catechism published in the 1860s. This manuscript seems to be a handwritten prayer book for use in Roman Catholic services. In poor condition, it remains a link to interpreting the styles and approaches of Roman Catholic missionaries to Canadian Micmac converts. -

Timeline Leading up to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement

Timeline Leading Up to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement 1820: Maine becomes a state and assumes all duties and obligations from Massachusetts arising from treaties and otherwise, and accepts monetary compensation for doing so. 1820-1975: Maine exercises increasingly pervasive authority over tribes, approved by Maine courts, while the Federal government fails to exercise its trust responsibility to the tribes. 1873: Maine Legislature removes treaty obligations language from printed Constitution. 1892: State v. Newell- Maine Law Court holds that Tribes are fully subject to State law. 1967: Maine Indians obtain the right to vote in state elections. 1968: Governor’s Task Force on Human Rights documents condition of Maine Indians. 1968: Indian Civil Rights Act enacted by Congress. PL 280 amended to require tribal consent to expansion of state jurisdiction. 1970-Present: New federal policy adopted to promote tribal self-government. Indian Self- Determination Act and numerous other federal laws passed to support tribal self- government. 1972: Passamaquoddy v. Morton filed in federal court. 1974- Maine Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights reports on circumstances of Maine Indians. 1975: Passamaquoddy v. Morton holds that the Non-Intercourse Act applies to the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the Penobscot Nation and recognizes the trust relationship between the Tribes and the United States. 1976: After Morton decision becomes final, Federal government acknowledges Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes as federally recognized tribes. 1979: State v. Dana holds that state criminal laws are not applicable to Indians on Indian lands in Maine. “Indian Country” under Federal Indian Law. 1979: Bottomly v. Passamaquoddy Tribe holds that tribes in Maine have same tribal sovereignty as other federally recognized tribes under Federal Indian Law.