Basketry of the Wabanaki Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Passamaquoddy, They Speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (Also Known As Maliseet- Passamaquoddy

1.1 Passamaquoddy, they speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also known as Maliseet- Passamaquoddy. It is an endangered language from the Algonquian language family (1) 1.2 Pqm (2) 1.3 45.3,-66.656 (3) 1.4 The Passamaquoddy tribe belonged to the loose confederation of eastern American Indians known as the Wabanaki Alliance, together with the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes. Today most Passamaquoddy people live in Maine, in two communities along the Passamaquoddy Bay that bears their name. However, there is also a band of a few hundred Passamaquoddy people in New Brunswick. The French referred to both the Passamaquoddy and their Maliseet kinfolk by the same name, "Etchimins." They were closely related peoples who shared a common language, but the two tribes have always considered themselves politically independent. Smallpox and other European diseases took a heavy toll on the Passamaquoddy tribe, which was reduced from at least 20,000 people to no more than 4000. Pressured by European and Iroquois aggression, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy banded together with their neighbors the Abenakis, Penobscots, and Micmacs into the short-lived but formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. This confederacy was no more than a loose alliance, however, and neither the Maliseet nor the Passamaquoddy nation ever gave up their sovereignty. Today the Passamaquoddy live primarily in the United States and the Maliseet in Canada, but the distinction between the two is not imposed by those governments--the two tribes have always been politically distinct entities. (4) 1.5 After working with the French and joining the Abnaki confederation against the English, many converted to Catholicism. -

Kit List for Canoe / Kayak Trip If You Are Unsure Please Don't Hesitate to Ask!

Kit List for Canoe / Kayak Trip Tips for your trip To Wear: Old trainers or similar (something you can swim in and will stay on your feet) Waterproofs (at least an anorak in case it rains, ideally waterproof trousers too) Warm top (even in summer, if the sun goes in it can get cold) Warm trousers (avoid jeans if possible) Hat (in summer a baseball cap or similar and if cold a woolly hat) Gloves (in cold weather) To take (dry barrel for canoeing/dry bag for kayaking): Spare clothes Towel Drink (soft drink or water. For full day trips at least 1 litre per person) Food (biscuits etc are good. Try to avoid fresh items like chicken, fish etc that could spoil in the hot sun). We can supply ration packs if required. Any medication and allergy medicine (i.e. inhalers, epipens etc) Spare trainers or boots (for after the activity) We provide dry barrels/bags and dry bags so you can keep your spare kit dry. If possible avoid wearing wellington boots (difficult to swim in). If you wear glasses it’s a good idea to tie some string to them. If it’s summer, then sun screen is a good idea. Avoid taking expensive electronic devices or jewellery in the canoe. There is limited room in a kayak to put KIT in so think carefully what you want to take. If you are unsure please don’t hesitate to ask! 01600 890027 or email [email protected] Wye Canoes Ltd Company No: 07161792 Registered Office: Hillcrest, Symonds Yat, Ross-on-Wye, HR9 6BN . -

A Report on Indian Township Passamaquoddy Tribal Lands In

A REPORT ON INDIAN TOWNSHIP PASSAMAQUODDY TRIBAL LANDS IN THE VICINITY OF PRINCETON, MAINE Anthony J. Kaliss 1971 Introduction to 1971 Printing Over two years have passed since I completed the research work for this report and during those years first one thing and ttan another prevented its final completion and printing. The main credit for the final preparation and printing goes to the Division of Indian Services of the Catholic Diocese of Portland and the American Civil Liberities Union of Maine. The Dioscese provided general assistance from its office staff headed by Louis Doyle and particular thanks is due to Erline Paul of Indian Island who did a really excellent job of typing more than 50 stencils of title abstracts, by their nature a real nuisance to type. The American Civil Liberities Union contrib uted greatly by undertaking to print the report Xtfhich will come to some 130 pages. Finally another excellent typist must be thanked and that is Edward Hinckley former Commissioner of Indian Affairs who also did up some 50 stencils It is my feeling that this report is more timely than ever. The Indian land problems have still not been resolved, but more and more concern is being expressed by Indians and non-Indians that something be done. Hopefully the appearance of this report at this time will help lead to some definite action whether in or out of the courts. Further research on Indian lands and trust funds remains to be done. The material, I believe, is available and it is my hope that this report will stimulate someone to undertake the necessary work. -

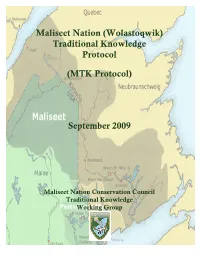

Traditional Knowledge Protocol

Maliseet Nation (Wolastoqwik) Traditional Knowledge Protocol (MTK Protocol) September 2009 Maliseet Nation Conservation Council Traditional Knowledge Working Group Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… i 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 2.0 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 2 3.0 Interpretation ………………………………………………………………… 3 4.0 MTK Methodology …………………………………………………………… 4 I Project Planning ………………………………………………………… 5 II Delivery and Implementation ……………………………………………… 6 III Finalizing Report and Disclosure ………………………………………… 7 5.0 Amendments …………………………………………………………………… 7 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………… 8 Maliseet Leadership Proclamation / Resolution …………………………… 9 Draft Maliseet Ethics Guidelines ……………………………………… 10 Foreword Development of the Maliseet Nation Traditional Knowledge (MTK) Protocol highlights the recognition of the importance of Aboriginal traditional knowledge in relation to the environmental issues facing Maliseet traditional territory, the Saint John River (Wolustok) watershed1. The protection of such knowledge has been identified by the Maliseet Chiefs as a crucial component for future relations with non-Aboriginals, as increasing development activity continues to cause concern for all parties on the best way to proceed, in the spirit of cooperation and with due respect for Maliseet Aboriginal and Treaty rights2. The protocol also addresses past problems with research projects such as lack of consultation of Maliseet people, lack of meaningful community involvement, lack of benefit from research, lack of informed consent, lack of community ownership of data (including analysis, interpretation, recording or access), and lack of respect of our culture and beliefs by outside researchers. Initiated by the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and produced through the combined efforts of informed Maliseet Elders, leaders, committees and grassroots volunteers, this protocol identifies the methods developed by the Maliseet Nation for the proper and thorough collection and use of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). -

A Chapter in Penobscot History

The Rebirth of a Nation? A Chapter in Penobscot History NICHOLAS N. SMITH Brunswick, Maine THE EARLIEST PERIOD The first treaty of peace between the Maine Indians and the English came to a successful close in 1676 (Williamson 1832.1:519), and it was quickly followed by a second with other Indians further upriver. On 28 April 1678, the Androscoggin, Kennebec, Saco and Penobscot went to Casco Bay and signed a peace treaty with commissioners from Massachusetts. By 1752 no fewer than 13 treaties were signed between Maine Indians negotiating with commissioners representing the Colony of Massachu setts, who in turn represented the English Crown. In 1754, George II of England, defining Indian tribes as "independent nations under the protec tion of the Crown," declared that henceforth only the Crown itself would make treaties with Indians. In 1701 Maine Indians signed the Great Peace of Montreal (Havard [1992]: 138); in short, the French, too, recognized the Maine tribes as sov ereign entities with treaty-making powers. In 1776 the colonies declared their independence, terminating the Crown's regulation of treaties with Maine Indians; beween 1754 and 1776 no treaties had been made between the Penobscot and England. On 19 July 1776 the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Micmac Indi ans acknowledged the independence of the American colonies, when a delegation from the tribes went to George Washington's headquarters to declare their allegiance to him and offered to fight for his cause. John Allan, given a Colonel's rank, was the agent for the Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Micmac, but refused to work with the Penobscot, .. -

A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Maine The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1977 A Brief History of the Passamaquoddy Indians Susan M. Stevens Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revised 1/77 A BRIEF HISTORY Pamp 4401 of the c.l PASSAMAQUODDY INDIANS By Susan M. Stevens - 1972 The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine are located today on two State Reservations about 50 miles apart. One is on Passamaquoddy Bay, near Eastport (Pleasant Point Reservation); the other is near Princeton, Maine in a woods and lake region (Indian Township Reservation). Populations vary with seasonal jobs, but Pleasant Point averages about 400-450 residents and Indian Township averages about 300- 350 residents. If all known Passamaquoddies both on and off the reservations were counted, they would number around 1300. The Passamaquoddy speak a language of the larger Algonkian stock, known as Passamaquoddy-Malecite. The Malecite of New Brunswick are their close relatives and speak a slightly different dialect. The Micmacs in Nova Scotia speak the next most related language, but the difference is great enough to cause difficulty in understanding. The Passamaquoddy were members at one time of the Wabanaki (or Abnaki) Confederacy, which included most of Maine, New Hampshire, and Maritime Indians. -

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations February 2017 Nicole Friederichs Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro Kate Bertino Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Contact Information: 120 Tremont Street Nicole Friederichs Boston, MA 02108 Practitioner-in-Residence Tel.: 1-617-305-1682 Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic Fax: 1-617-573-8100 Suffolk University Law School Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC) is honored to offer this thorough review of the crafting of the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721-1735. In June of 2014, the MITSC completed the Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine where the MITSC offered the following framework: The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, (MICSA), was passed in October of the same year [1980]. The MICSA gave federal permission for the [state Maine Implementing Act] (MIA) to take effect while retaining intact the federal trust relationship between the federally recognized tribes of Maine and the US Congress; and placed constraints on the implementation of the MIA. Of particular interest to the inquiry into the saltwater fishery conflict between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the State of Maine are the following provisions of the federal act: 1. MICSA (25 U.S.C. § 1735 (a)) provides that “In the event a conflict of interpretation between the provisions of the Maine Implementing Act and this Act should emerge, the provisions of this Act shall govern.” The provisions of the federal MICSA thus override the MIA provisions when there is a conflict between the two. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

A Lesson in Stone: Examining Patterns of Lithic Resource Use and Craft-Learning in the Minas Basin Region of Nova Scotia By

A Lesson in Stone: Examining Patterns of Lithic Resource Use and Craft-learning in the Minas Basin Region of Nova Scotia By © Catherine L. Jalbert A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2011 St. John’s Newfoundland Abstract Examining the Late Woodland (1500-450 BP) quarry/workshop site of Davidson Cove, located in the Minas Basin region of Nova Scotia, a sample of debitage and a collection of stone implements appear to provide correlates of the novice and raw material production practices. Many researchers have hypothesized that lithic materials discovered at multiple sites within the region originated from the outcrop at Davidson Cove, however little information is available on lithic sourcing of the Minas Basin cherts. Considering the lack of archaeological knowledge concerning lithic procurement and production, patterns of resource use among the prehistoric indigenous populations in this region of Nova Scotia are established through the analysis of existing collections. By analysing the lithic materials quarried and initially reduced at the quarry/workshop with other contemporaneous assemblages from the region, an interpretation of craft-learning can be situated in the overall technological organization and subsistence strategy for the study area. ii Acknowledgements It is a pleasure to thank all those who made this thesis achievable. First and foremost, this thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and support provided by my supervisor, Dr. Michael Deal. His insight throughout the entire thesis process was invaluable. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story

Spirit Bear: Honouring Memories, Planting Dreams Based on a True Story Written by Cindy Blackstock Illustrated by Amanda Strong Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N) zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee- chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc – (N)zalkwaksten Hul’qumi’num – Oh Siem! Michif – L’oneur Mi’kmaq – Kepmite’lmanej French – Honorer Ktunaxa – Wil=il=wi.na tkil=? Muskegoinninew (Swampy Cree) – Esitawenimacik Honouring Omushkego Inninu (James Bay Cree) – Kistenee-chiikewin Maliseet – Ulasuwiyal Plains Cree – Kistanimuchick Gitxsan – Hlo’omsxw St’at’imc -

Canoe/Kayak Club

All skill levels are accommo- The CMM Canoe/Kayak Club CALVERT MARINE MUSEUM dated, with lessons in basic canoeing offers museum members an oppor- offered to beginners upon occa- tunity to explore the creeks, marshes, CANOE & KAYAK CLUB CANOE & KAYAK sion. and rivers in southern Maryland as part of an organized excursion The CMM Canoe/Kayak Club guided by a trip leader. offers free canoe rides and instruc- A trip is scheduled approxi- tions during Sharkfest and PRAD mately once a month with the em- (Patuxent River Appreciation Days). phasis on morning excursions lasting two to three hours. Most trips end at lunchtime, often in a location with a place to eat. QUESTIONS? Contact John Altomare at (410) 610-2253 or by email at [email protected]. Guests are welcome, as well as For further information on joining the paddlers wishing to learn about the Calvert Marine Museum, check the CMM club by joining a trip. website www.calvertmarinemuseum. com or call (410) 326-2042. CMM museum canoes and kayaks are available as “loaners” for members needing an extra boat. You must be a member of the P.O. Box 97, Solomons, MD 20688 Calvert Marine Museum to join the 410-326-2042 • FAX 410-326-6691 Exploring new Canoe/Kayak Club. Md Relay for Impaired Hearing or Speech: places with new Statewide Toll Free 1-800-735-2258 www.calvertmarinemuseum.com friends. QUESTIONS? Contact John Altomare at (410) 610-2253 or Accommodations will be made for individuals by email at [email protected]. with disabilities upon reasonable notice. -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work.