University of Alberta the Im/Possibility of Recovery in Native North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature in Canada 1967-1972: Part One1

H ARTMUT L UTZ The Beginnings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature in Canada 1967-1972: Part One1 _____________________ Zusammenfassung Die Feiern zum hundertjährigen Jubiläum des Staates Kanada im Jahre 1967 boten zwei indianischen Künstlern Gelegenheit, Auszüge ihrer Literatur dem nationalen Publi- kum vorzustellen. Erst 1961 bzw. 1962 waren Erste Nationen und Inuit zu wahlberechtig- ten Bürgern Kanadas geworden, doch innerhalb des anglokanadischen Kulturnationa- lismus blieben ihre Stimmen bis in die 1980er Jahre ungehört. 1967 markiert somit zwar einen Beginn, bedeutete jedoch noch keinen Durchbruch. In Werken kanonisierter anglokanadischer Autorinnen und Autoren jener Jahre sind indigene Figuren überwie- gend Projektionsflächen ohne Subjektcharakter. Der Erfolg indianischer Literatur in den USA (1969 Pulitzer-Preis an N. Scott Momaday) hatte keine Auswirkungen auf die litera- rische Szene in Kanada, doch änderte sich nach Bürgerrechts-, Hippie- und Anti- Vietnamkriegsbewegung allmählich auch hier das kulturelle Klima. Von nicht-indigenen Herausgebern edierte Sammlungen „indianischer Märchen und Fabeln“ bleiben in den 1960ern zumeist von unreflektierter kolonialistischer Hybris geprägt, wogegen erste Gemeinschaftsarbeiten von indigenen und nicht-indigenen Autoren Teile der oralen Traditionen indigener Völker Kanadas „unzensiert“ präsentierten. Damit bereiteten sie allmählich das kanadische Lesepublikum auf die Veröffentlichung indigener Texte in modernen literarischen Gattungen vor. Résumé À l’occasion des festivités entourant le centenaire du Canada, en 1967, deux artistes autochtones purent présenter des extraits de leur littérature au public national. En 1961, les membres des Premières Nations avaient obtenu le droit de vote en tant que citoyens canadiens (pour les Inuits, en 1962 seulement), mais au sein de la culture nationale anglo-canadienne, leur voix ne fut guère entendue jusqu’aux années 1980. -

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden's Three Day Road

Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Neta Gordon ore than three-quarters of the way through Three Day Road, a novel portraying the fictional experiences of two Cree men fighting for Canada during the Great War, the historicalM figure Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwe soldier known for his success as a World War One sniper, finally makes an appearance. Rumours of Pegahmagabow’s feats have reached Boyden’s protagonist, Xavier Bird, and his best friend, Elijah Whiskeyjack; Elijah in particu- lar is keen to compare exploits with “Peggy,” especially to weigh his own kills against those of the infamous “Indian,” rumoured to be “the best hunter of us all” (187).1 An important objective of this encounter between fictional and historical figures is to emphasize an extratextual function of Three Day Road, which Boyden explicitly delineates in his acknowledgements: “I wish to honour the Native soldiers who fought in the Great War, and in all wars in which they so overwhelmingly vol- unteered. Your bravery and skill do not go unnoticed” (353). Boyden’s use here of a helping verb phrase of negation — “do not” — draws special attention to the main part of the predicate “go unnoticed,” and thus reveals the irony of his claim; the scene featuring Peggy proposes that Aboriginal soldiers were not at all “honoured” for their service in the Great War, and that this service in fact went quite aggressively “unnoticed.” As Boyden himself admits in a recent interview with Herb Wyile, “I think my acknowledgements were more wishful thinking than anything” (222). -

Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’S Three Day Road Neta Gordon

Document generated on 09/27/2021 11:01 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Neta Gordon Volume 33, Number 1, 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl33_1art06 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gordon, N. (2008). Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 33(1), 118–135. All rights reserved © Management Futures, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Neta Gordon ore than three-quarters of the way through Three Day Road, a novel portraying the fictional experiences of two Cree men fighting for Canada during the Great War, the historicalM figure Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwe soldier known for his success as a World War One sniper, finally makes an appearance. Rumours of Pegahmagabow’s feats -

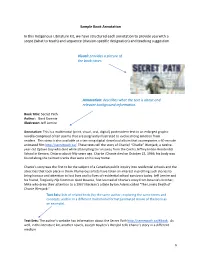

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Use of Canadian Books in Ontario Public and Catholic Intermediate and Secondary English Departments: Results of a Survey of Teachers of Grades 7 Through 12

Use of Canadian Books in Ontario Public and Catholic Intermediate and Secondary English Departments: Results of a Survey of Teachers of Grades 7 through 12 Catherine M.F. Bates 18 June 2017 [email protected] The Use of Canadian Books in Ontario Public and Catholic Intermediate and Secondary English Departments 1 Contents Contents ......................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................... 2 Research Methodology .................................................. 2 Findings .......................................................................... 3 Results of Book Inventory .............................................. 3 Additional Analysis of Canadian Works in the Sample ... 6 Types of Works ............................................................... 8 Selection Process and Resources ................................... 9 Opinions on Importance ............................................... 13 Conclusion .................................................................... 14 References .................................................................... 15 Annex A: Inventory of Books Taught in Grade 7-12 English Classes in Ontario 16 Funding for this study was provided by Ontario Media Development Corporation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ontario Media Development Corporation or the Government of Ontario. The Government -

Aboriginal Literatures in Canada: a Teacher's Resource Guide

Aboriginal Literatures in Canada A Teacher’s Resource Guide Renate Eigenbrod, Georgina Kakegamic and Josias Fiddler Acknowledgments We want to thank all the people who were willing to contribute to this resource through interviews. Further we wish to acknowledge the help of Peter Hill from the Six Nations Polytechnic; Jim Hollander, Curriculum Coordinator for the Ojibway and Cree Cultural Centre; Patrick Johnson, Director of the Mi’kmaq Resource Centre; Rainford Cornish, librarian at the Sandy Lake high school; Sara Carswell, a student at Acadia University who transcribed the interviews; and the Department of English at Acadia University which provided office facilities for the last stage of this project. The Curriculum Services Canada Foundation provided financial support to the writers of this resource through its Grants Program for Teachers. Preface Renate Eigenbrod has been teaching Aboriginal literatures at the postsecondary level (mainly at Lakehead University, Thunder Bay) since 1986 and became increasingly concerned about the lack of knowledge of these literatures among her Native and non- Native students. With very few exceptions, English curricula in secondary schools in Ontario do not include First Nations literatures and although students may take course offerings in Native Studies, these works could also be part of the English courses so that students can learn about First Nations voices. When Eigenbrod’s teaching brought her to the Sandy Lake Reserve in Northwest Ontario, she decided, together with two Anishnaabe teachers, to create a Resource Guide, which would encourage English high school teachers across the country to include Aboriginal literatures in their courses. The writing for this Resource Guide is sustained by Eigenbrod’s work with Aboriginal students, writers, artists, and community workers over many years and, in particular, on the Sandy Lake Reserve with the high school teachers at the Thomas Fiddler Memorial High School, Georgina Kakegamic and Josias Fiddler. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT TITEL DER DIPLOMARBEIT “The Politics of Storytelling”: Reflections on Native Activism and the Quest for Identity in First Nations Literature: Jeannette Armstrong’s Slash, Thomas King’s Medicine River, and Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach. VERFASSERIN Agnes Zinöcker ANGESTREBTER AKADEMISCHER GRAD Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, im Mai 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz Acknowledgements To begin with, I owe a debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz. He supported me in stressful times and patiently helped me to sort out my ideas about and reflections on Canadian literature. He introducing me to the vast field of First Nations literature, shared his insights and provided me with his advice and encouragements to develop the skills necessary for literary analysis. I am further indebted to express thanks to the ‘DLE Forschungsservice und Internationale Beziehungen’, who helped me complete my degree by attributing some funding to do research at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. I also wish to address special thanks to Prof. Misao Dean from the University of Victoria for letting me join some inspiring discussions in her ‘Core Seminar on Literatures of the West Coast’, which gave me the opportunity to exchange ideas with other students working in the field of Canadian literature. Lastly, I warmly thank my parents Dr. Hubert and Anna Zinöcker for their devoted emotional support and advice, and for sharing their knowledge and experience with me throughout my education. -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

The Windigo in Joseph Boyden's Three Day Road

Culturally Conceptualizing Trauma: The Windigo in Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Vikki Visvis nfluential trauma theorist Cathy Caruth suggests that “trauma itself may provide the very link between cultures ” (Trauma 11). However, despite Caruth’s optimistic vision of psychopathol- Iogy as a vehicle for cross-cultural dialogue, the theoretical formula- tions of trauma in current theories tend to privilege Eurocentric dis- courses and thus are inherently founded on a principle of elision. This Eurocentric perspective is apparent in the works of individual critics such as Cathy Caruth and Judith Herman, both of whom rely on a Western psychoanalytic tradition. Caruth is heavily indebted to Sigmund Freud’s insights in Beyond the Pleasure Principle while Herman’s work is par- ticularly informed by the theories of Pierre Janet. This commitment to Western psychoanalytic paradigms is apparent not only in the works of individual critics but also in those of theorists who have historicized the concept of trauma. Ruth Leys’s genealogy of trauma and testimony is exclusively informed by concepts derived from Western psychoanalysis, medicine, and literary theory. Similarly, Allan Young’s Foucauldian approach to trauma, which historicizes the specific discourses from which various psychological forms of trauma have been constructed, relies exclusively on North American and European paradigms. Patrick J. Bracken points to this tendency in current discourses of trauma, rec- ognizing that the “supposition is that the forms of mental disorder that have been found in the West, and described by Western psychiatry, are basically the same as those found elsewhere” (41). He posits that “in non-Western settings, idioms of distress are likely to be quite differ- ent” (55) and ultimately encourages a deconstructive hermeneutics that reveals discourses of trauma as forms of “ethnopsychiatry: a particu- lar, culturally based way of thinking about and responding to states of madness and distress” (40).