Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden's Three Day Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’S Three Day Road Neta Gordon

Document generated on 09/27/2021 11:01 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Neta Gordon Volume 33, Number 1, 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl33_1art06 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gordon, N. (2008). Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 33(1), 118–135. All rights reserved © Management Futures, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Time Structures and the Healing Aesthetic of Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Neta Gordon ore than three-quarters of the way through Three Day Road, a novel portraying the fictional experiences of two Cree men fighting for Canada during the Great War, the historicalM figure Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwe soldier known for his success as a World War One sniper, finally makes an appearance. Rumours of Pegahmagabow’s feats -

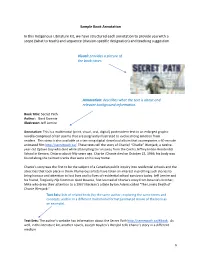

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Use of Canadian Books in Ontario Public and Catholic Intermediate and Secondary English Departments: Results of a Survey of Teachers of Grades 7 Through 12

Use of Canadian Books in Ontario Public and Catholic Intermediate and Secondary English Departments: Results of a Survey of Teachers of Grades 7 through 12 Catherine M.F. Bates 18 June 2017 [email protected] The Use of Canadian Books in Ontario Public and Catholic Intermediate and Secondary English Departments 1 Contents Contents ......................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................... 2 Research Methodology .................................................. 2 Findings .......................................................................... 3 Results of Book Inventory .............................................. 3 Additional Analysis of Canadian Works in the Sample ... 6 Types of Works ............................................................... 8 Selection Process and Resources ................................... 9 Opinions on Importance ............................................... 13 Conclusion .................................................................... 14 References .................................................................... 15 Annex A: Inventory of Books Taught in Grade 7-12 English Classes in Ontario 16 Funding for this study was provided by Ontario Media Development Corporation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ontario Media Development Corporation or the Government of Ontario. The Government -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

The Windigo in Joseph Boyden's Three Day Road

Culturally Conceptualizing Trauma: The Windigo in Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road Vikki Visvis nfluential trauma theorist Cathy Caruth suggests that “trauma itself may provide the very link between cultures ” (Trauma 11). However, despite Caruth’s optimistic vision of psychopathol- Iogy as a vehicle for cross-cultural dialogue, the theoretical formula- tions of trauma in current theories tend to privilege Eurocentric dis- courses and thus are inherently founded on a principle of elision. This Eurocentric perspective is apparent in the works of individual critics such as Cathy Caruth and Judith Herman, both of whom rely on a Western psychoanalytic tradition. Caruth is heavily indebted to Sigmund Freud’s insights in Beyond the Pleasure Principle while Herman’s work is par- ticularly informed by the theories of Pierre Janet. This commitment to Western psychoanalytic paradigms is apparent not only in the works of individual critics but also in those of theorists who have historicized the concept of trauma. Ruth Leys’s genealogy of trauma and testimony is exclusively informed by concepts derived from Western psychoanalysis, medicine, and literary theory. Similarly, Allan Young’s Foucauldian approach to trauma, which historicizes the specific discourses from which various psychological forms of trauma have been constructed, relies exclusively on North American and European paradigms. Patrick J. Bracken points to this tendency in current discourses of trauma, rec- ognizing that the “supposition is that the forms of mental disorder that have been found in the West, and described by Western psychiatry, are basically the same as those found elsewhere” (41). He posits that “in non-Western settings, idioms of distress are likely to be quite differ- ent” (55) and ultimately encourages a deconstructive hermeneutics that reveals discourses of trauma as forms of “ethnopsychiatry: a particu- lar, culturally based way of thinking about and responding to states of madness and distress” (40). -

The Dominance of White Authors in Canadian Literary Awards

White Voices: The Dominance of White Authors in Canadian Literary Awards Kara Locke Abstract An analysis of the past winners of Canada's three largest English-language fiction awards, as well as the non-fiction award with the largest monetary prize. This article examines the ratio of white authors to those of visible racial minority, and considers the cultural and economic impacts of awarding primarily white authors in a racially diverse country. Keywords: Literary Awards Literary awards have long been a way to shine a spotlight on exceptional authors and stories. A combination of attributed prestige, exposure and monetary reward, winning one of these awards can drastically alter the career of a writer. By effectively amplifying the voices of the authors who are awarded, these prizes select what and who Canadians will be reading, and contribute to the shaping of what we recognize as Canadian culture. Canada is known for being multicultural, a diverse mix of the different peoples who have come to inhabit the land, so it stands to reason that our list of award winning authors would reflect that. It does not. The archive of past winners is overwhelmingly white. The oldest award in Canada is the Governor General’s Award for English- language fiction, created in 1936 by the Canadian Author’s Association, and taken over by the Canada Council for the Arts in 1959 (ggbooks.ca/about) . The winner receives a $25,000 prize. The deliberation process is carried out through peer evaluation, with other authors, often past winners themselves, choosing a winner of the finalists. -

Books Change People's Lives

Books change people’s lives They educate, inspire and simply put smiles on kids’ faces. Webcom is honoured to be part of this thrilling experience, providing the community with the best quality books. Webcom is proud to be the official Our innovative program BookFWD™ print provider of The Word On The gives publishers flexibility to order only Street Festival Program and KidStreet what they need, when they need it. Festival Guide. With 35 years of experience and over 10,000 book orders annually, Webcom partners with publishers to deliver complete business solutions. Map out your Festival Make planning fun and easy. An interactive festival map and event program, powered by Webview, are available online: www.thewordonthestreet.ca/wots/toronto To find out more, please visit www.webcomlink.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Words of Welcome 6 Behind the Curtain HOW TO USE THIS 7 Literacy Comes Alive PROGRAM 8 Festival Partners Review the Festival at a Glance on 10 Festival at a Glance pages 10 - 14, or go directly to the 16 Official Booksellers venue descriptions 17 Bestsellers Stage 23 Great Books Marquee 31 Nothing But The Truth Tent 38 The Remarkable Reads Tent 45 This Is Not The Shakespeare Stage 53 Toronto Book Awards Tent 59 Toronto Star Tent 62 Vibrant Voices of Ontario Tent 69 Wordshop Marquee 74 Exhibitor Listings 78 Festival Special Listings 82 Festival Map Illustration: Dave Murray Program Design: Gary Taugher Design Co. WORDS OF WELCOME Festival Greetings from The Word On The Street! Welcome to this year’s festival! On behalf of the Board of Directors, staff and volunteers, we are pleased to celebrate the best in Canadian writing and the importance of reading in the lives of all Torontonians. -

The Orenda Joseph Boyden

The Orenda Joseph Boyden Discussion Questions 1. The Orenda is told from the alternating perspective of three narrators, but is periodically punctuated by the voice of an omniscient narrator. Discuss the significance of this voice. Who or what does this represent? Com- pare the passage that begins the book with the one at the end of the novel. What do these passages assert about the legacy of the Huron people? The influence of the Jesuits? 2. Discuss the Jesuit’s mission to bring Christianity to the New World. Are Christophe’s intentions pure? Would you classify his attempts at converting the Hurons as successful? What tensions arose in the community be- cause of his efforts? 3. How does the Jesuit’s mission to bring Christianity to the New World coincide with Champlain’s vision for con- quering the area? How does it conflict? 4. The relationship between Bird and Snow Falls fully evolves over the course of The Orenda. When it begins, Snow Falls’ hatred of Bird is unabashed, yet by the end of the novel she thinks of him as her father. How does this change occur? What challenges did their relationship face before Snow Falls came to terms with her role as daughter? 5. The Orenda takes place over the course of several years, showcasing Snow Falls’ development from pre- pubescence to motherhood. How is womanhood marked in the Huron culture? How do other women in the vil- lage help to guide her? 6. How does the relationship between Bird and Christophe evolve over time? Do you think the men respect each other, despite their differences? 7. -

University of Alberta the Im/Possibility of Recovery in Native North

University of Alberta The Im/possibility of Recovery in Native North American Literatures by Nancy Lynn Van Styvendale A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Nancy Lynn Van Styvendale Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Teresa Zackodnik, English and Film Studies Daphne Read, English and Film Studies Stephen Slemon, English and Film Studies Chris Andersen, Native Studies Shari Huhndorf, Ethnic Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies, University of Oregon Dedication To Aloys Neil Mark Fleischmann, for love, cats, dinners and questions, always the questions. Abstract Recovery is a ubiquitous theme in Native North American literature, as well as a repeated topic in the criticism on this literature, but the particulars of its meaning, mechanics, and ideological implications have yet to be explored by critics in any detail.