Mars Effect’: Anatomy of a Pseudo-Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yjyjjgl^Ji^Jihildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? the Claims of Aroma .••

NOVA EXAMINES ALIEN ABDUCTIONS • THE WEIRD WORLD WEB • DEBUNKING THE MYSTICAL IN INDIA yjyjjgl^ji^JiHildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? The Claims of Aroma .•• Fun and Fallacies with Numbers I by Marilyn vos Savant le Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT IHf CENIK FOR INQUKY (ADJACENT IO IME MATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director Lee Nisbet. Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock.* psychologist, York Murray Gell-Mann. professor of physics, H. Narasimhaiah, physicist, president, Univ., Toronto Santa Fe Institute; Nobel Prize laureate Bangalore Science Forum, India Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Dorothy Nelkin. sociologist. New York Univ. Albany, Oregon Univ. Joe Nickell.* senior research fellow, CSICOP Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Henry Gordon, magician, columnist. Lee Nisbet.* philosopher, Medaille College Toronto Kentucky James E. Oberg, science writer Stephen Barrett. M.D., psychiatrist, Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Health Sciences Univ. Pa. C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Mark Plummer, lawyer, Australia Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., AI Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Canada Laboratory W. V. Quine, philosopher. Harvard Univ. Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Chicago Southern California understanding and cognitive science, Carl Sagan, astronomer. -

CFI-Annual-Report-2018.Pdf

Message from the President and CEO Last year was another banner year for the Center the interests of people who embrace reason, for Inquiry. We worked our secular magic in a science, and humanism—the principles of the vast variety of ways: from saving lives of secular Enlightenment. activists around the world who are threatened It is no secret that these powerful ideas like with violence and persecution to taking the no others have advanced humankind by nation’s largest drugstore chain, CVS, to court unlocking human potential, promoting goodness, for marketing homeopathic snake oil as if it’s real and exposing the true nature of reality. If you medicine. are looking for humanity’s true salvation, CFI stands up for reason and science in a way no look no further. other organization in the country does, because This past year we sought to export those ideas to we promote secular and humanist values as well places where they have yet to penetrate. as scientific skepticism and critical thinking. The Translations Project has taken the influential But you likely already know that if you are reading evolutionary biology and atheism books of this report, as it is designed with our supporters in Richard Dawkins and translated them into four mind. We want you not only to be informed about languages dominant in the Muslim world: Arabic, where your investment is going; we want you to Urdu, Indonesian, and Farsi. They are available for take pride in what we have achieved together. free download on a special website. It is just one When I meet people who are not familiar with CFI, of many such projects aimed at educating people they often ask what it is we do. -

De Kruidenelixers Van Jan Smit Uit Veendam

K Nederlands Tijdschrift td tegen de NT Kwakzalverij JAARGANG 125 | 2014 | 4 Kackadorisprijs Jan Smit Zien en niet zien Het Nederlands Tijdschrift tegen de Kwakzalverij (v/h Actieblad, v/h Maandblad tegen de Kwakzalverij) is een uitgave van de Vereniging tegen de Kwakzalverij, vereniging tot evaluatie van alternatieve behandelmethoden en tot bestrijding van kwakzalverij ADVIESRAAD Prof. dr. J. A. den Boer, hoogleraar biologische psychiatrie Prof. dr. P. Borst, emeritus hoogleraar klinische biochemie Prof. dr. D. D. Breimer, emeritus hoogleraar farmacologie Prof. dr. W. M. J. Levelt, emeritus hoogleraar psycholinguïstiek Prof. dr. A. Rijnberk, emeritus hoogleraar interne geneeskunde gezelschapsdieren REDACTIE B. van Dien, [email protected] Aanleveren van kopij, maximaal 1500 woorden, in Word. Afbeeldingen dienen als aparte bestanden aangeleverd te worden, elektronische figuren tif- of jpeg-format, minimaal 600 pixels. De redactie behoudt zich het recht voor artikelen en brieven te redigeren en in te korten. De auteurs verlenen impliciet toestemming voor openbaarmaking van hun bijdrage in de elektroni- sche uitgave van het Nederlands Tijdschrift tegen de Kwakzalverij. Jaarabonnement: e 37,50 Losse nummers: e 9,50 ISSN: 1571-5469 Omslagtekening: VolZicht door Peter Welleman Vereniging tegen de Kwakzalverij opgericht 1 januari 1881 Correspondentieadres: Harmoniehof 65, 1071 TD Amsterdam tel: 0620616743, e-mail: [email protected] BESTUUR Voorzitter: mw. C. J. de Jong, anesthesiologe, Amsterdam Secretaris: prof. dr. F. S. A. M. van Dam, psycholoog, Amsterdam Penningmeester: drs. R. Giebels, econoom, Amsterdam LEDEN G. R. van den Berg, psychiater, Amsterdam Dr. M. J. ter Borg, MDL-arts, Veldhoven Dr. T. P. C. Dorlo, farmacoloog, Amsterdam Mr. Th. J. Douma, oud-advocaat, Leiden Prof. -

De Duiding Ontraadseld: Naar De Kern Van De Horoscopie

De duiding ontraadseld Naar de kern van de horoscopie Jan Kampherbeek Colofon Gepubliceerd door Dutch2000. ISBN/EAN: 978-90-819417-1-6. http://jankampherbeek.nl/duiding. Ontwerp voorkant Jan Kampherbeek. Dutch2000, Enschede, september 2012. Copyright 2012 Jan Kampherbeek. Dit e-boek is niet beschermd tegen kopiëren. Je mag het op meerdere apparaten installeren. Ik heb de prijs bewust laag gehouden, daarom is het prettig als je dit boek niet kopieert voor derden. Inhoud • Inleiding • Dank • Noten en referenties • Deel 1. Antwoorden en vragen • De eerste vraag: Hoe kan het dat astrologen verschillende en vaak tegenstrijdige technieken gebruiken? • Technieken die door een deel van de astrologen worden gebruikt • Tegenstrijdige technieken • De tweede vraag: Waarom zijn er zoveel astrologische technieken zonder astronomische grondslag? • Progressieve astrologie • De derde vraag: Verkeerde of zelfs fictieve geboortetijden leiden vaak tot goede duidingen. Hoe is dat te verklaren? • De vierde vraag: Astrologie werkt, maar waarom blijft astrologie in wetenschappelijk onderzoek bijna nooit overeind? • Veel gemaakte fouten • Niet te bewijzen • En tóch werkt het • Deel 2 - Astrologische benaderingen • Rationele en causale astrologie • Michel Gauquelin • Geen antwoorden • Theosofische en esoterische astrologie • Geen verklaring • Psychologische astrologie • Geen verklaring • Synchroniciteit • Een eerste poging tot verklaring • Symbolische astrologie • Een deelverklaring • Welke vragen resteren? • Deel 3 - De bronnen van de astrologie • Voortekenen -

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

Homeopathie - Wikipedia

21-6-2020 Homeopathie - Wikipedia Homeopathie Neem het voorbehoud bij medische informatie in acht. Raadpleeg bij gezondheidsklachten een arts. Homeopathie (Oud Grieks: ὅμοιος, homoios, gelijksoortig en πάθος, pathos, lijden of ziekte) is een pseudowetenschappelijke therapie gebaseerd op de ideeën van de Duitse arts Samuel Hahnemann. Het belangrijkste daarvan is het gelijksoortigheidsbeginsel, dat inhoudt dat een homeopathisch geneesmiddel volgens Hahnemann geschikt is voor de behandeling van een ziekte als het middel bij een gezond persoon dezelfde ziekteverschijnselen opwekt als die waaraan de zieke lijdt. Homeopathische middelen De homeopathische behandeling bestaat uit het voorschrijven van homeopathica, dat wil zeggen potentiëringen (stapsgewijze sterke verdunningen in combinatie met schudden) van stoffen die in pure vorm dezelfde symptomen als de te bestrijden ziekte zouden oproepen. Hoewel homeopathie een van de meest onderzochte alternatieve geneeswijzen is, wordt de toegeschreven klinische werkzaamheid niet ondersteund door wetenschappelijk bewijs. De werking van homeopathie is niet groter dan die van placebo's.[1][2][3][4][5][6] Homeopathie wordt daarom tot de pseudowetenschappen gerekend.[7][8] Inhoud Principe Stromingen Klassieke homeopathie Uitgangspunten Klinische homeopathie Complexe homeopathie Geschiedenis Leerlingen Homeopathische behandelwijze Bereiding van homeopathische middelen Simplex- en complexmiddelen Gebruik van homeopathische middelen Beschouwing van ziekte en genezing Interactie tussen ziektes Minimale dosis -

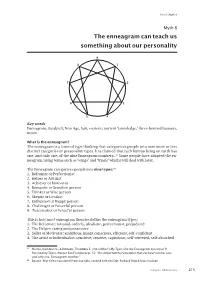

The Enneagram Can Teach Us Something About Our Personality

Part III | Myth 8 Myth 8 The enneagram can teach us something about our personality 9 8 1 7 2 6 3 5 4 Key words Enneagram, Gurdjieff, New Age, Sufi, esoteric, ancient ‘knowledge,’ three-brained humans, moon. What is the enneagram? The enneagram is a form of type thinking that categorizes people into nine more or less distinct categories or personality types. It is claimed that each human being on earth has one, and only one, of the nine Enneagram numbers..93 Some people have adapted the en- neagram, using terms such as ‘wings’ and ‘triads’ which I will deal with later. The Enneagram categorizes people into nine types:94 1. Reformer or Perfectionist 2. Helper or Altruist 3. Achiever or Motivator 4. Romantic or Sensitive person 5. Thinker or Wise person 6. Skeptic or Loyalist 7. Enthusiast or Happy person 8. Challenger or Powerful person 9. Peacemaker or Peaceful person This is how most enneagram theories define the enneagram types: 1. The Reformer: rational, orderly, idealistic, perfectionist, prejudiced 2. The Helper: caring and possessive 3. Seller or Motivator: ambitious, image conscious, efficient, self-confident 4. The artist or Individualist: sensitive, creative, capricious, self-centered, self-absorbed 93 Hurley, Kathleen V., & Dobson, Theodore E. (1991) What’s My Type: Use the Enneagram System of 9 Personality Types. Harper San Francisco: p. 15: "It is important to remember that each person has one, and only one, Enneagram number." 94 Source: first titles translated from Luc Sala, second titles by Don Richard Riso & Russ Hudson. A skeptic’s HR Dictionary 215 5. -

Clever Hans's Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers' Cognitive Dissonance Csicon Nashville Highlights

SI March April 13 cover_SI JF 10 V1 1/31/13 10:54 AM Page 2 Scotland Mysteries | Herbs Are Drugs | The Pseudoscience Wars | Psi Replication Failure | Morality Innate? the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 37 No. 2 | March/April 2013 ON INVISIBLE BEINGS Clever Hans’s Successors Testing Indian Astrology Believers’ Cognitive Dissonance CSICon Nashville Highlights Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry March April 13 *_SI new design masters 1/31/13 9:52 AM Page 2 AT THE CEN TERFOR IN QUIRY –TRANSNATIONAL Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Robert L. Park,professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; of breast surgery section, Wayne State University Observatory, Williams College Newton, MA School of Medicine. John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, Clifford A. -

El Escéptico N. 2

el escéptico La revista para el fomento de la razón y la ciencia Publicación trimestral - Número 2 (Otoño 1998) El arca de Noé de los seres extraordinarios De Condon a Sturrock: los ovnis se estrellan con la ciencia Ascenso de lo irracional La Academia de Lagado El misterio de Rennes-le-Château el ARP - Sociedad para el Avance escéptico del Pensamiento Crítico La revista para el fomento de la razón y la ciencia PRESIDENTE DIRECCIÓN Javier E. Armentia Luis Alfonso Gámez Astrofísico, director del Planetario de Pamplona SUBDIRECCIÓN José María Bello SECRETARIO Fernando L. Frías Ferrán Tarrasa Ingeniero industrial, CONSEJO EDITORIAL Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya Félix Ares de Blas Javier E. Armentia María Teresa Giménez Barbat TESORERO Sergio López Borgoñoz Alfonso López Borgoñoz Gerente de Antares Producció i Distribució SL Borja Marcos Fernando Peregrín Oscar Soria ASESOR JURÍDICO Fernando L. Frías Carlos Tellería Abogado Victoria Toro José J. Uriarte MAQUETACIÓN Alfonso Afonso Cano SECCIONES Desde el sillón, Fernando Peregrín El circo paranormal, F.L. Frías/B. Marcos Guía digital, Ernesto J. Carmena DOCUMENTACIÓN Xabier Berdaguer RELACIÓN PARCIAL DE SOCIOS Adela G. Espelta Miguel Ángel Almodóvar (Periodista científico); Da- Adela Torres vid Alvargonzález (Filósofo, Universidad de Ovie- do); Félix Ares de Blas (Informático, Universidad TRADUCCIONES del País Vasco); (Arqueólogo, di- Iñaki Camiruaga José María Bello rector del Museo Arqueológico e Histórico de La Borja Marcos Antonio Vizcarra Coruña); Henri Broch (Físico, Universidad -

SKEPTIKKO 12/13, Syksy 1991

SKEPTIKKO Mars ja EY Hengen ja tiedon messut Psykoterapialaki? Pörssiennuste Numero 12/13 Syksy 1991 2 SKEPTIKKO 12/13, syksy 1991 Skepsiksen hallitus: Nils Mustelin (puheenjohtaja), Pekka Roponen (Skeptikon päätoimittaja, varapuheenjohtaja), Lauri Gröhn (sihteeri), Markku Javanainen (rahastonhoitaja), Ilkka Tuomi. Tieteellinen neuvottelukunta: dosentti S. Albert Kivi- nen (puheenjohtaja), professori Nils Edelman, apulaispro- fessori Kari Enqvist, amanuenssi Harry Halén, profes- sori Pertti Hemánus, dosentti Raimo Keskinen, professori Kirsti Lagerspetz, professori Raimo Lehti, professori Anto Leikola, LKT Matti A. Miettinen, professori Ilkka Niini- luoto, dosentti Heikki Oja, professori Heikki Räisänen, pro- fessori Anssi Saura, ohjelmajohtaja, FL Tytti Sutela, profes- sori Raimo Tuomela, professori Yrjö Vasari, professori Jo- han von Wright ja dosentti Risto Vuorinen. Jäsenasioista, lehtitilauksista ja muista yhdistyksen toimintaan liittyvistä kysymyksistä pyydetään neuvottelemaan sihteerin kanssa, puh. 90-538677 tai postitse: Lauri Gröhn Ojahaanpolku 8 B 17 01600 Vantaa SKEPTIKKO-lehden toimitus: päätoimittaja Pekka Ropo- nen, muut toimitusneuvoston jäsenet: Matti Virtanen ja Nils Mustelin. Päätoimittaja, puh. 918-8192609 (työ), postiosoite: Pekka Roponen Tahtikatu 3 15810 Lahti ISSN 0786-2571 SKEPTIKKO 12/13, syksy 1991 3 Sisällys 4 Usko ja tieteisusko, Pekka Roponen 5 Palvelukseen halutaan 6 Mars ja EY epäilyksen alaisina, Matti Virtanen 19 Hengen ja tiedon messut, Markku Javanainen 29 Kuka saa harjoittaa psykoterapiaa, Pekka Roponen -

Kritiekloos Vaccineren Pseudowetenschap in De Psychologie

Tijdschrift België - Belgique Toelating — Gesloten Verpakking P. B. 9000 Gent — 3/430 9000 Gent 1 3/8886 wonder en is gheen wonder PSYCHOLOGIE Pseudowetenschap in de psychologie Wat is het en wat kunnen we er aan doen? GEZONDHEID Kritiekloos vaccineren Niet meer van deze tijd? INTERVIEW Oud-huisarts-epidemioloog Dick Bijl: “Veel mensen slikken medicijnen die niet werken” ESSAY Water omhoog scheppen (shovelling water uphill) Erkenningsnummer P309799 Afzendadres: Kwartaaltijdschrift - 18de jaargang, Herfstnummer 2018 Paul De Belder Afgiftekantoor 9000 Gent 1 Waversebaan 203, 3001 Heverlee wonder en is gheen wonder EDITOGeestelijke gezondheid in de kering tijdschrift voor wetenschap en rede De klinische psychologen kregen (eindelijk, na vele jaren politiek gehakketak) een wettelijke erkenning als uitvoerders van een beroep in de gezondheidszorg. Dat De titel van dit tijdschrift Wonder en is gheen Wonder opent nieuwe perspectieven voor mensen met psychische problemen die proberen heeft betrekking op de toelichting van Simon Stevin om in een versplinterd landschap van geestelijke gezondheidszorg de weg te vinden (Brugs wiskundige, natuurkundige en bouwkundige, naar de zorg of hulp die hen past. 1548-1620) onder zijn klootkransbewijs: ook wat er Huisartsen zijn nauwelijks opgeleid voor het begeleiden van mensen met kleine of vreemd uitziet kan een natuurlijke verklaring hebben. grote psychische moeilijkheden. Psychiaters zijn moeilijk bereikbare specialisten, die ook niet opgeleid zijn om eerste hulp te bieden bij emotionele kneuzingen. Die eerste hulp is nochtans cruciaal, want kleine emotionele verwondingen kunnen etterende chronische psychische problemen worden, al dan niet versterkt door emotioneel ondermijnende situaties zoals armoede, geweld of verslaving. De geestelijke gezondheidszorg is bovendien beladen met stigma en wordt daardoor Wonder en is Gheen Wonder is nog moeilijker bereikbaar. -

Universe. and Carl Sagan

GARDNER ON THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM • CURSES • GOULD'S ROCKS OF AGES Skeptical Inquire THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 23, No. 6 • November/December 1999 ^^^^HB ^J P^^^^V^^V i^r^^r^^ • ^1 IHBF .^HH BK^*HI MB&^fc*^.^jjr^ ..r — ^ i • vs 1 \ ** * • 1 r•A^'w ff *• "^1 •& 1 I ^. .»& w j i \ M MTh 8 & A •e •EsP - • ff Si ~ Hff? ^SSK&V--'' • _-• ^•^^My^w-^w B I Universe. and Carl Sagan Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL |ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nicked, Senior Research Fellow Lee Nisbet Special Projects Director Matthew Nisbet, Public Relations Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock," psychologist, York Univ., I Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Univ. Dorothy Nelkin, sociologist. New York Univ. Toronto Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Joe Nickell,* senior research fellow, CSICOP Steve Allen, comedian, author, composer, Toronto Lee Nisbet* philosopher, Medaille College pianist Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Bill Nye, science educator and television Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. host, Nye Labs Albany, Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts James E. Oberg, science writer Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Kentucky University of Miami Health Sciences Univ. Stephen Barrett M.D., psychiatrist, author, C.