Growing Together Articulates a Number of Proposals That Can Help the Region Exploit Its Huge Untapped Potential for Regional Economic Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

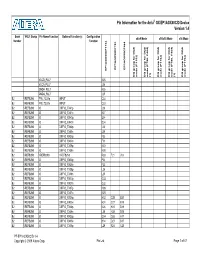

Pin-Outs (PDF)

Pin Information for the Arria® GX EP1AGX50C/D Device Version 1.4 Bank VREF Group Pin Name/Function Optional Function(s) Configuration x8/x9 Mode x16/x18 Mode x36 Mode Number Function EP1AGX50DF780 EP1AGX50CF484 EP1AGX50DF1152 DQ group for DQS DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode DQS for group DQ (F780, F484) mode (1) DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode DQS for group DQ (F780, F484) mode (1) DQS for group DQ (F1152) mode VCCD_PLL7 K25 VCCA_PLL7 J26 GNDA_PLL7 K26 GNDA_PLL7 J25 B2 VREFB2N0 FPLL7CLKp INPUT C34 B2 VREFB2N0 FPLL7CLKn INPUT C33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX41p J28 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX41n K27 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX40p E34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX40n D34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX40p J30 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX40n J29 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX39p F32 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX39n F31 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX39p K30 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX39n K29 B2 VREFB2N0 VREFB2N0 VREFB2N0 R30 T21 J18 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX38p F34 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX38n F33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX38p L26 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX38n L25 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX37p G33 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX37n G32 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX37p M26 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX37n M25 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX36p H32 C28 B20 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX36n H31 C27 B19 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX36p K28 H23 D19 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX36n L28 H22 D18 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX35p G34 D28 A17 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_RX35n H34 D27 B17 B2 VREFB2N0 IO DIFFIO_TX35p L29 F24 C20 PT-EP1AGX50C/D-1.4 Copyright © 2009 Altera Corp. Pin List Page 1 of 47 Pin Information for the Arria® GX EP1AGX50C/D Device Version -

AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health www.racgp.org.au Healthy Profession. Healthy Australia. AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health Disclaimer The information set out in this publication is current at the date of first publication and is intended for use as a guide of a general nature only and may or may not be relevant to particular patients or circumstances. Nor is this publication exhaustive of the subject matter. Persons implementing any recommendations contained in this publication must exercise their own independent skill or judgement or seek appropriate professional advice relevant to their own particular circumstances when so doing. Compliance with any recommendations cannot of itself guarantee discharge of the duty of care owed to patients and others coming into contact with the health professional and the premises from which the health professional operates. Accordingly, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and its employees and agents shall have no liability (including without limitation liability by reason of negligence) to any users of the information contained in this publication for any loss or damage (consequential or otherwise), cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information contained in this publication and whether caused by reason of any error, negligent act, omission or misrepresentation in the information. Recommended citation The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Curriculum for Australian General Practice 2016 – AH16 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2016. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 100 Wellington Parade East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Australia Tel 03 8699 0510 Fax 03 9696 7511 www.racgp.org.au Published May 2016 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners We recognise the traditional custodians of the land and sea on which we work and live. -

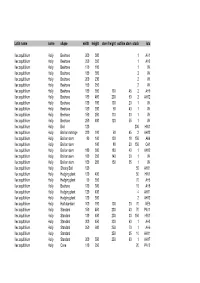

Ilex Specifications

Latin name name shape width height stem height outline stem stock lots Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 200 300 1 AH1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 250 350 1 AH2 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 170 180 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 350 2 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 200 230 2 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 150 250 2 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 350 130 45 2 AH9 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 450 200 60 2 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 130 180 100 20 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 180 200 50 40 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 150 250 110 30 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 250 400 120 55 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball 120 200 HW1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on mini tige 220 180 60 45 2 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 80 160 100 18 150 AK4 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 160 80 20 150 CA1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 180 300 180 40 1 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 180 250 140 30 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Ball on stem 150 250 150 35 1 VK Ilex aquifolium Holly Shruby Ball 120 55 AH11 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 120 400 50 HW1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 60 350 70 AH5 Ilex aquifolium Holly Beehave 130 300 15 AH6 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 120 400 4 AH11 Ilex aquifolium Holly Hedging plant 120 350 2 AH12 Ilex aquifolium Holly Half standard 100 180 100 20 70 NE5 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 150 450 200 40 70 PA11 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 130 450 200 30 150 HW1 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 300 450 200 60 1 AH3 Ilex aquifolium Holly Standard 350 600 -

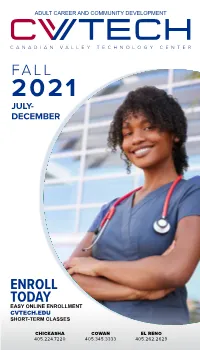

Enroll Today Easy Online Enrollment Cvtech.Edu Short-Term Classes

ADULT CAREER AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CANADIAN VALLEY TECHNOLOGY CENTER FALL 2021 JULY- DECEMBER ENROLL TODAY EASY ONLINE ENROLLMENT CVTECH.EDU SHORT-TERM CLASSES CHICKASHA COWAN EL RENO 405.224.7220 405.345.3333 405.262.2629 FALL 2021 CATALOG TABLE OF CONTENTS SHORT-TERM COURSES | JULY-DECEMBER ONLINE & BLENDED DANCING / MUSIC ....................................................4 FABRIC / YARN ...........................................................4 ALL ONLINE & BLENDED COURSES .................. 2 HEALTH / WELLNESS. ............................................. 5 BUSINESS HOME / AUTO MAINTENANCE. ........................... 5 & COMPUTERS LANGUAGE ................................................................ 5 MISCELLANEOUS .................................................... 5 ACCOUNTING / QUICKBOOKS ............................ 2 PERSONAL FINANCE. ............................................. 5 COMPUTER BASICS ................................................ 2 WRITING...................................................................... 5 COMPUTER CERTIFICATIONS .............................. 2 MICROSOFT OFFICE ............................................... 2 MODERN DESIGN / CADD ..................................2-3 TRADE, SAFETY & INDUSTRY HEALTH AUTOMOTIVE / DRIVING ....................................... 5 CPR / FIRST AID .........................................................3 ENERGY INDUSTRY ................................................. 5 DENTAL FIELD ............................................................3 -

SAARC Countries I Ii Seminar Book

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Future-of-Eco-Coop-in-SARRC- Countries Shah, Syed Akhter Hussain Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Islamabad 2014 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/59275/ MPRA Paper No. 59275, posted 30 Dec 2014 23:42 UTC Future of Economic Cooperation in SAARC Countries i ii Seminar Book Future of Economic Cooperation in SAARC Countries iii CONTENTS Acknowledgements Acronyms Introduction 1 Welcome Address 12 Ambassador (R) Sohail Amin Opening Remarks 15 Kristof W. Duwaerts Inaugural Address 18 Riaz Mohammad Khan Concluding Address 24 Dr. Ishrat Hussain Concluding Remarks 26 Kristof W. Duwaerts Vote of Thanks 27 Ambassador (R) Sohail Amin Recommendations 29 CHAPTER 1 Regional Trade — Driver for Economic Growth 37 Dr. Kamal Monnoo CHAPTER 2 Meeting Energy Requirement: Potential for Intra-regional Energy Trade 61 Dr. Janak Lal Karmacharya CHAPTER 3 Building Regional Transport and Communication Infrastructure 81 Ms. Arshi Saleem Hashmi iv Seminar Book CHAPTER 4 Developing Energy Corridor from Central and West Asia to South Asia 101 Prof. Savita Pande CHAPTER 5 The New Silk Road Initiative: Economic Dividends 119 Mr. Nabi Sroosh and Mr.Yosuf Sabir CHAPTER 6 China‟s Growing Economic Relations with South Asia 127 Dr. Liu Zongyi CHAPTER 7 Fast Tracking Economic Collaboration in SAARC Countries 146 Dr. Pervez Tahir CHAPTER 8 Towards an Asian Century: Future of Economic Cooperation in SAARC Countries: A View from FPCCI 159 Mr. Muhammad Ali CHAPTER 9 Economic Cooperation among SAARC Countries: Political Constraints 163 Dr. Rashid Ahmad Khan CHAPTER 10 Implications of Bilateral and Sub-regional Trade Agreements on Economic Cooperation: A Case Study of SAARC in South Asia 177 Dr. -

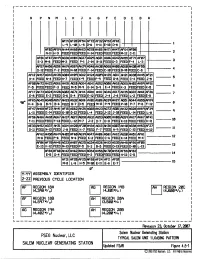

Salem Generating Station, Units 1 & 2, Revision 29 to Updated Final Safety Analysis Report, Chapter 4, Figures 4.5-1 to 4.5

r------------------------------------------- 1 I p M J B I R N L K H G F E D c A I I I I I Af'Jq AF20 AF54 AF72 32 AF52 AF18 I L-q L-10 L-15 D-6 -11 E-10 D-8 l I AF03 Af't;qAH44 AH60 AH63 AG70 AH65 AH7l AH47 AFS4 AF08 I N-ll H-3 FEED FEED FEED H-14 FEED FEED FEED M-12 C-11 2 I AF67 AH4q AH04 AG27 AG2<i' AG21 AG16 AG42 AF71 AF07 AF01 AG36 AH!5!5 3 I E-3 M-6 FEED M-3 FEED P-1 J-14 B-11 FEED D-3 FEED F-4 L-3 I AF67 AH5S AG56 Atflq AGsq AH2<1' AG48 AH30 AG68 AH08 AG60 AH30 AF55 I D-12 FEED F-2 FEED N-11 FEED F-14 FEED C-11 FEED B-11 FEED C-8 4 I AF12 AH57 AG43 AH38 AHtiJq AG12 AH24 AGfR AH25 AGil AG31 AH45 AF21 AGlM AH21 5 I H~4 FEED N-4 FEED H-7 FEED K~q FEED F-q FEED G-8 FEED C-4 FEED J-15 I AF50 AH72 AH22 AGS6 AH15 AGll.lAG64 AG41 AG52 AG88 AH18 AG65 AHIJ2 AH5q AF51 I F-5 FEED FEED F-3 FEED M-5 r+q G-14 o-q E-4 FEED K-3 FEED FEED K-5 6 I f:Fl7 AH73 AG24 AH28 AG82 AG71 AH14 AG18 AHil AG46 AG17 AH35 AG22 AH61 AF26 7 I E-8 FEED E-2 FEED G-6 G-4 FEED E-12 FEED J-4 J-6 FEED L-2 FEED E-5 I Af&q I qeo AF65 AG45 AtM0 AG57 AH33 AG32 AG16 AH01 AGI6 AG3<1' AH27 AG51 AG44 AG55 K-4 B-8 e-q B-6 FEED B-7 P-5 FEEC M-11 P-q FEED P-11 P-7 P-8 F-12 8 I AF47 AH68 AF23 AH41 AF1!5 AG62 AH26 AG03 AH23 AH32 AG28 AHsq AF3<1' q I L-U FEED E-14 FEED G-10 G-12 FEED L-4 FEED FEED L-14 FEED L-8 I ~~ AF66 AH66 AH10 AG67 AH37 AGJq AG68 AG3l AG63 AG05 AH08 AG5q AH17 AH67 AF41 I F-11 FEED FEED F-13 FEED L-12 M-7 J-2 D-7 D-11 FEED K-13 FEED FEED K-11 10 I AE33 AH!52 AG37 AH31 AG14 AH20 AF20 AH34 AG13 AH36 AG07 AH40 AG38 AH!53 AF27 I G-ll FEED N-12 FEED J-8 FEED K-7 FEED -

The Transport Trend of Thailand and Malaysia

Executive Summary Report The Potential Assessment and Readiness of Transport Infrastructure and Services in Thailand for ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Content Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Rationales 1 1.2 Objectives of Study 1 1.3 Scopes of Study 2 1.4 Methodology of Study 4 2. Current Status of Thailand Transport System in Line with Transport Agreement of ASEAN Community 2.1 Master Plan and Agreement on Transport System in ASEAN 5 2.2 Major Transport Systems for ASEAN Economic Community 7 2.2.1 ASEAN Highway Network 7 2.2.2 Major Railway Network for ASEAN Economic Community 9 2.2.3 Main Land Border Passes for ASEAN Economic Community 10 2.2.4 Main Ports for ASEAN Economic Community 11 2.2.5 Main Airports for ASEAN Economic Community 12 2.3 Efficiency of Current Transport System for ASEAN Economic Community 12 3. Performance of Thailand Economy and Transport Trend after the Beginning of ASEAN Economic Community 3.1 Factors Affecting Cross-Border Trade and Transit 14 3.2 Economic Development for Production Base Thriving in Thailand 15 3.2.1 The analysis of International Economic and Trade of Thailand and ASEAN 15 3.2.2 Major Production Bases and Commodity Flow of Prospect Products 16 3.2.3 Selection of Potential Industries to be the Common Production Bases of Thailand 17 and ASEAN 3.2.4 Current Situation of Targeted Industries 18 3.2.5 Linkage of Targeted Industries at Border Areas, Important Production Bases, 19 and Inner Domestic Areas TransConsult Co., Ltd. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi 2T Consulting and Management Co., Ltd. -

3 Cd Changer Mini Mini Component Max-S720/S720s/S725 Max-Zs720/Zs720g

3 CD CHANGER MINI MINI COMPONENT MAX-S720/S720S/S725 MAX-ZS720/ZS720G SERVICE Manual MIMI MIMI COMPONENT SYSTEM CONTENTS 1. Alignment and Adjustments 2. Exploded Views and Parts List 3. Electrical Parts List 4. Block Diagrams 5. PCB Diagrams 6. Wiring Diagram 7. Schematic Diagrams - Confidential - 1. Alignment and Adjustments 1-1. Tuner FM FM THD Adjustment Output Antenna SET GND SSG FREQ. 98 MHz Terminal Oscilloscope Adjustment FM S.S.G Input point FM DETECTOR COIL Speaker (FM DET) Terminal output Input Output 60 dB Distortion Meter Minumum Distortion (0.4% below) (Figure 1-1) Figure1-1 IF CENTER and THD Adjustment FM Search Level Adjustment FM Antenna SSG FREQ. 98 MHz 28 dB Adjustment BEACON SET point SENSITIVITY GND (SVR1) SEMI-VR(10KΩ) FM S.S.G FM IN Output 28 dB(±2dB) 20 kΩ * Adjustment Location of Tuner PCB Adjust SVR1 (Figure 1-2) *Adjust FM S.S.G level to 28dB AM(MW) OSC AM(MW) RF LW OSC LW RF ITEAM Figure1-2 FM Auto Search Level Adjustment Adjustment Adjustment Adjustment Adjustment Received FREQ. 522~1611 KHz 594 KHz 146~290 KHz 150 KHz Adjustment MO MA LO LA point AM(MW) I.F Adjustment 60cm Maximum Output 1~7.0±0.5V Maximum 2~7.0±0.5V Output(Fig1-4) Output(Fig1-4) SSG FREQ. 450 kHz AM IF Frequency 522 kHz OUTPUT AM ANT IN Adjustment point AM IF AM SSG Speaker Terminal 450KHZ Maximum output (Figure 1-3) INPUT OUTPUT VTVM Oscilloscope Figure1-3 AM I.F Adjustment Fig 1-4 OSC Voltage Samsung Electronics 1-1 Alignment and Adjustments 1-1-2 AM(MW),LW,SW1,SW2 Adjustment Circuit Measuring Instrument & Step S.S.G Radio dial Adjusting Adjust for to be Arrangement Frequency Setting Point Adjusted 1 522KHz 522KHz MW OSC Adjust for 1.0V±0.1V at the low. -

Tracer Modelling and Heat Mining Calculations for the Ahuachapan Geothermal Field El Salv Ador C.A

" Q~ The United Nations zrs: University GEOTHERMAL TRAINING PROGRAMME Reports 1996 Orkustofnun, Grensasvegur 9, Number 2 IS-108 Reykjavik, Iceland IAEA Project ELS/B/005 TRACER MODELLING AND HEAT MINING CALCULATIONS FOR THE AHUACHAPAN GEOTHERMAL FIELD EL SALV ADOR C.A. Francisco E. Montalvo L. Com isi6n Ejecutiva Hidroelectrica del Rio Lempa (C .E.L.), Centra de Investigaciones Geotermicas (C.LG.). km 11 Y2 Carretera al Puerto La Libertad, Santa Teela, La Libertad, EL SAL V ADOR C.A. ABSTRACT Nine tracer test experiments using Ill\ and one using Jl l' were carried out in the Ahuachapan geothermal field during 1987 to 1992. In only six of the tests some tracer recovery was reported ranging from 0.1 % to 28% for individual wells. In order to obtain a one-dimensional fracture flow model estimate of reservoir geometry parameters, several simulations were carried out using the TRJNV code for selected tests that show the higher tracer recovery values. The simulations provide a support for the conceptual reservoir model as the tracer velocities in the southern upflow zone of the field, are more than 10 times higher than when the tracer is injected in the north-east part, where colder downflow influences the reservoir. The results of the tracer simulations were used as input for simulating heat mining from the reservoir during long tenn injection. A reservoir parameters sensitivity study was carried out using different values of porosity, injection temperatures, formation temperatures, constant and variable injection flow rates, fracture thickness and height. Additional high pressure steam and additional thermal power recovery due to the injection were also estimated. -

Tear It up and Start Again!

www.grapevine.is THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO LIFE, TRAVEL & ENTERTAINMENT IN ICELAND IN THE ISSUE Issue 01 • 2011 • January 7 - February 3 + COMPLETE CITY LISTINGS - INSIDE! Tear it up and start again! What happened during the last decade? How can we avoid messing up the new one? : ) Phew. New decade time. This is a joyous occasion, as the one we're leaving behind was by most accounts a failed one (although it did have some awesome bits in between). In our first issue of this shiny new decade, we consult historians, poets, CEOs, authors, politicians, artists, businessfolks, teenagers and seniors alike to try and determine just what happened, and what's in store. The Reykjavík Grapevine Issue 1 — 2011 THE REYKJAVÍK GRAPEVINE Hafnarstræti 15, 101 Reykjavík 2 www.grapevine.is [email protected] Editorial | Haukur S. Magnússon Published by Fröken ehf. www.froken.is Member of the Icelandic Travel Industry Association www.saf.is Printed by Landsprent ehf. in 25.000 copies. EDITOR: Haukur S Magnússon / [email protected] JOURNALIST: Valgerður Þóroddsdóttir / [email protected] HOPE and CHANGE and stuff EDITORIAL: +354 540 3600 / [email protected] ADVERTISING: +354 540 3605 / [email protected] PUBLISHER: Hilmar Steinn Grétarsson / [email protected] I watched the Prime Minister’s address on New +354 540 3601 / [email protected] Year’s Eve. I should not have bothered. There were CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: no surprises. It was Your Standard Prime Minister Eísabet Jökulsdóttir Of Iceland’s New Year’s Address, with no original Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson Ásmundur Ásmundsson thought (nor commentary, nor ideas, nor sign of Eiríkur Örn Norðdahl life) managing to seep through the thick cloak of Sigríður Þorgeirsdóttir mundane mediocrity that Iceland’s government Bart Cameron Kristín Eiríksdóttir seems determined to shroud itself in. -

T&B Cable Tray

T&B Cable Tray Metallic – Aluminum Table of Contents Metallic – Aluminum ................................................. A33 –A110 Overview ........................................................................................A35 Straight Lengths .................................................................... A36–A49 Fittings .................................................................................. A50–A87 Explaining the Fitting Styles ................................................... A50–A51 Horizontal Fittings Selection Guide ......................................... A53–A55 Vertical Fittings Selection Guide ............................................. A56–A59 U-Style Fittings – Horizontal Bends 90º / 60º..................................A60 H-Style Fittings – Horizontal Bends 90º / 60º .................................A61 U-Style Fittings – Horizontal Bends 45º / 30º ..................................A62 H-Style Fittings – Horizontal Bends 45º / 30º ..................................A63 U-Style Fittings – Horizontal Tee, Cross ..........................................A64 H-Style Fittings – Horizontal Tee, Cross ..........................................A65 U-Style Fittings – Horizontal Reducing Tee .....................................A66 H-Style Fittings – Horizontal Reducing Tee .....................................A67 U-Style Fittings – Horizontal Expanding Tee ....................................A68 H-Style Fittings – Horizontal Expanding Tee ....................................A69 U-Style Fittings – Horizontal -

Dating of Remains of Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens from Anatolian Region by ESR-US Combined Methods: Preliminary Results

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 5, ISSUE 05, MAY 2016 ISSN 2277-8616 Dating Of Remains Of Neanderthals And Homo Sapiens From Anatolian Region By ESR-US Combined Methods: Preliminary Results Samer Farkh, Abdallah Zaiour, Ahmad Chamseddine, Zeinab Matar, Samir Farkh, Jamal Charara, Ghayas Lakis, Bilal Houshaymi, Alaa Hamze, Sabine Azoury Abstract: We tried in the present study to apply the electron spin resonance method (ESR) combined with uranium-series method (US), for dating fossilized human teeth and found valuable archaeological sites such as Karain Cave in Anatolia. Karain Cave is a crucial site in a region that has yielded remains of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, our direct ancestors. The dating of these remains allowed us to trace the history, since the presence of man on earth. Indeed, Anatolia in Turkey is an important region of the world because it represents a passage between Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Our study was conducted on faunal teeth found near human remains. The combination of ESR and US data on the teeth provides an understanding of their complex geochemical evolution and get better estimated results. Our samples were taken from the central cutting where geological layers are divided into archaeological horizons each 10 cm. The AH4 horizon of I.3 layer, which represents the boundary between the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic, is dated to 29 ± 4 ka by the ESR-US model. Below, two horizons AH6 and AH8 in the same layer I.4 are dated respectively 40 ± 6 and 45 ± 7 ka using the ESR-US model.