Asia-Europe Connectivity Vision 2025

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Dr Nguyen Phuong Binh IIR, Vietnam Introdu

SESSION SEVEN Mapping the Second Decade of East Asian Community Building (Draft only) Dr Nguyen Phuong Binh IIR, Vietnam Introduction: East Asia has become an increasingly significant region for trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) penetration. Among the top 10 global trading economies (with EU 27 counted as one), half are from East Asia. China, Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore are respectively, the world’s third, fourth, sixth, seventh and ninth biggest traders. East Asia’s new influence is not only being felt in the global economy, but also in politics, culture and technology. The region’s economic weight gives it a voice and a role in Asia - Pacific and the world stage. With the first ASEAN plus 3 (China, Japan and South Korea) informal meeting in Kuala Lumpur in December 1997 and the first East Asia Summit in 2005, the ASEAN plus 3 process has been under way and the East Asian Community building (ASEAN plus 3 plus Australia, New Zealand and India) is evolving. Directions and suggestions for mapping the second decade of East Asian Community building will be partly discussed in this paper. Reviewing East Asia Cooperation Process: In the past ten years, many cooperation mechanisms have been set up and consolidated by regional countries. In political and security cooperation: East Asian summit, ASEAN Plus Three cooperation, Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC), ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), etc. In economic and financial cooperation: East Asian Finance Ministers’ Meeting, currency swap and bond market, Asian currency unit, GMS, and East Asian Economic Community, etc. These cooperation mechanisms not only brought about mutual benefits to participating states, but also forged better understanding and closer relations among them in spite of their differences as to the levels of economic development, political regime, religion and culture. -

REDEFINING EUROPE-AFRICA RELATIONS Contents

The European Union’s relations with the African continent are facing distinct challenges, with the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic making it all the more evident that the prevail- ing asymmetry is no longer REDEFINING acceptable as we move into the future. EUROPE-AFRICA This analysis takes a closer RELATIONS look at economic relations between the European Union Robert Kappel and Africa, which for some time now have been on a January 2021 downward trajectory, and addresses the impact of the global pandemic at the same time. Additionally, the paper outlines the current political cooperation between the two continents and evaluates the EU’s recent strategy pro- posal. Lastly, the key aspects of more comprehensive stra- tegic cooperation between Europe and Africa are iden tified. REDEFINING EUROPE-AFRICA RELATIONS Contents Summary 2 1 EU-AFRICAN ECONOMIC RELATIONS 3 2 EFFECTS OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON AFRICAN ECONOMIES 14 3 COOPERATION WITH AFRICA: FROM LOMÉ TO A COMPREHENSIVE STRATEGY WITH AFRICA 18 4 FORGING A STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION 20 Résumé: Paving the Way for a New Africa-Europe Partnership 28 Literature 30 1 FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – REDEFINING EUROPE-AFRICA RELATIONS Summary The European Union’s (EU) relations with the African conti- This paper begins by describing the EU’s current economic nent are facing a distinct set of challenges. Contrary to the relations with Africa (Chapter 1), which have been on a expectations of both African and European governments, downward trajectory for quite some time already. The ef- the pending negotiations between the partners are now fects of the Covid-19 pandemic are then outlined in Chap- being put to the test like never before. -

Opening up Europe's Public Data

The European Data Portal: Opening up Europe’s public data data.europa.eu/europeandataportal it available in the first place? What we do And in what domains, or A third of European across domains and across More and more volumes of countries are leading the countries? Also in what data are published every day, way with solid policies, language should the data be every hour, every minute, every licensing norms, good available? second. In every domain. portal traffic and many local Across every geography, small initiatives and events Value focuses on purpose, or big. The amount of data re-use and economic gains of across the world is increasing Open Data. Is there a societal exponentially. A substantial gain? Or perhaps a demo- amount of this data is cratic gain? How many new collected by governments. Public Sector Information jobs are created? What is the is information held by the critical mass? Value is there. The European Data Portal public sector. The EU Directive The question is how big? harvests the metadata on the re-use of Public (data about the data) of Sector Information provides Public Sector Information a common legal framework The Portal available on public data and for a European market for geospatial portals across government-held data. It is The first official version of European countries. Portals built around the key pillars of the European Data Portal is can be national, regional, the internal market: free flow available since February 2016. local or domain specific. of data, transparency and fair Within the Portal, sections are They cover the EU Member competition. -

Realizing the Low-Carbon Future

GLOBAL SOLUTIONS JOURNAL ∙ ISSUE 5 BEYOND GREENWASHING: INSTRUMENTS TO FIGHT CLIMATE CHANGE AND PROTECT THE PLANET’S RESOURCES cording to 2017 data, the US still produces that a low-carbon transition could require Realizing the twice as much as carbon dioxide per capita $3.5 trillion in energy sector investments as China and nearly nine times as much every year for decades – twice the current as India, highlighting the increased envi- rate. Under the agency’s scenario, in order low-carbon future ronmental impact of higher standards of for carbon emissions to stabilize by 2050, living. All of this means the Paris Climate nearly 95% of the electricity supply must Agreement’s goal of limiting the global be low carbon, 70% of new cars must be What role for central banks and monetary temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Cel- electric, and the carbon-dioxide intensity sius could be a pipe dream if energy in- of the building sector must fall by 80%. authorities? vestments worldwide do not change. For markets to anticipate and smooth The economy-wide changes needed to the transition to a low-carbon world, they attain a low-carbon future are enormous: need information, proper risk manage- a massive reallocation of capital is need- ment and coherent, credible public-policy The author: ABSTRACT ed, which presents unprecedent risks and frameworks. That could be strengthened Placing both advanced and developing opportunities to the financial system. The by central banks and monetary authori- Venkatachalam countries on a low-carbon path requires International Energy Agency estimates ties. Anbumozhi an unprecedented shift in private invest- Senior Energy Economist, ments and new financing models. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

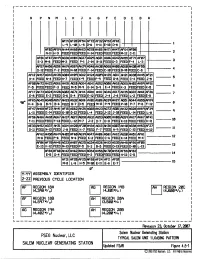

Salem Generating Station, Units 1 & 2, Revision 29 to Updated Final Safety Analysis Report, Chapter 4, Figures 4.5-1 to 4.5

r------------------------------------------- 1 I p M J B I R N L K H G F E D c A I I I I I Af'Jq AF20 AF54 AF72 32 AF52 AF18 I L-q L-10 L-15 D-6 -11 E-10 D-8 l I AF03 Af't;qAH44 AH60 AH63 AG70 AH65 AH7l AH47 AFS4 AF08 I N-ll H-3 FEED FEED FEED H-14 FEED FEED FEED M-12 C-11 2 I AF67 AH4q AH04 AG27 AG2<i' AG21 AG16 AG42 AF71 AF07 AF01 AG36 AH!5!5 3 I E-3 M-6 FEED M-3 FEED P-1 J-14 B-11 FEED D-3 FEED F-4 L-3 I AF67 AH5S AG56 Atflq AGsq AH2<1' AG48 AH30 AG68 AH08 AG60 AH30 AF55 I D-12 FEED F-2 FEED N-11 FEED F-14 FEED C-11 FEED B-11 FEED C-8 4 I AF12 AH57 AG43 AH38 AHtiJq AG12 AH24 AGfR AH25 AGil AG31 AH45 AF21 AGlM AH21 5 I H~4 FEED N-4 FEED H-7 FEED K~q FEED F-q FEED G-8 FEED C-4 FEED J-15 I AF50 AH72 AH22 AGS6 AH15 AGll.lAG64 AG41 AG52 AG88 AH18 AG65 AHIJ2 AH5q AF51 I F-5 FEED FEED F-3 FEED M-5 r+q G-14 o-q E-4 FEED K-3 FEED FEED K-5 6 I f:Fl7 AH73 AG24 AH28 AG82 AG71 AH14 AG18 AHil AG46 AG17 AH35 AG22 AH61 AF26 7 I E-8 FEED E-2 FEED G-6 G-4 FEED E-12 FEED J-4 J-6 FEED L-2 FEED E-5 I Af&q I qeo AF65 AG45 AtM0 AG57 AH33 AG32 AG16 AH01 AGI6 AG3<1' AH27 AG51 AG44 AG55 K-4 B-8 e-q B-6 FEED B-7 P-5 FEEC M-11 P-q FEED P-11 P-7 P-8 F-12 8 I AF47 AH68 AF23 AH41 AF1!5 AG62 AH26 AG03 AH23 AH32 AG28 AHsq AF3<1' q I L-U FEED E-14 FEED G-10 G-12 FEED L-4 FEED FEED L-14 FEED L-8 I ~~ AF66 AH66 AH10 AG67 AH37 AGJq AG68 AG3l AG63 AG05 AH08 AG5q AH17 AH67 AF41 I F-11 FEED FEED F-13 FEED L-12 M-7 J-2 D-7 D-11 FEED K-13 FEED FEED K-11 10 I AE33 AH!52 AG37 AH31 AG14 AH20 AF20 AH34 AG13 AH36 AG07 AH40 AG38 AH!53 AF27 I G-ll FEED N-12 FEED J-8 FEED K-7 FEED -

The EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy and Its Impact on Asia-Europe Relations

The EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy and Its Impact on Asia-Europe Relations Bart Gaens INTRODUCTION The EU is gradually adapting to a more uncertain world marked by increasing geo- political as well as geo-economic competition. Global power relations are in a state of flux, and in Asia an increasingly assertive and self-confident China poses a chal- lenge to US hegemony. The transatlantic relationship is weakening, and question marks are being placed on the future of multilateralism, the liberal world order and the rules-based global system. At least as importantly, China is launching vast con- nectivity and infrastructure development projects throughout Eurasia, sometimes interpreted as a geostrategic attempt to re-establish a Sinocentric regional order. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in particular, focussing on infrastructure devel- opment and investments in over 80 countries, including some within Europe, has been causing concern at regional as well as global levels. At the most recent BRI summit in April 2019 Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China had signed new deals amounting to 64 billion USD, underscoring Beijing’s continuing cheque book diplomacy.1 It is clear that these ongoing dynamics potentially have important ramifica- tions for Europe’s own prosperity, in terms of trade and economy but also security. Overall however, the EU has been slow to react, in particular in formulating a re- sponse to connectivity challenges. In September 2018 the EU published its first coordinated attempt to formulate the European vision on connectivity and infra- structure development, in the form of a European connectivity strategy for Asia, officially entitled a Joint Communication on “Connecting Europe and Asia – building blocks for an EU strategy”. -

Kazakhstan Missile Chronology

Kazakhstan Missile Chronology Last update: May 2010 As of May 2010, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the Kazakhstan Missile Overview. This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2009-1947 March 2009 On 4 March 2009, Kazakhstan signed a contract to purchase S-300 air defense missile systems from Russia. According to Ministry of Defense officials, Kazakhstan plans to purchase 10 batteries of S-300PS by 2011. Kazakhstan's Air Defense Commander Aleksandr Sorokin mentioned, however, that the 10 batteries would still not be enough to shield all the most vital" facilities designated earlier by a presidential decree. The export version of S- 300PS (NATO designation SA-10C Grumble) has a maximum range of 75 km and can hit targets moving at up to 1200 m/s at a minimum altitude of 25 meters. -

ชื่อจังหวัด อำเภอ ตำบล เขต และแขวง Changwat, Khet and Amphoe Directory

ชื่อจังหวัด อ ำเภอ ต ำบล เขต และแขวง CHANGWAT, KHET AND AMPHOE DIRECTORY กรุงเทพมหำนคร เขตพระนคร Khet Phra Nakhon KRUNG THEP MAHA แขวงชนะสงครำม Khwaeng Chana Songkhram NAKHON (BANGKOK) แขวงตลำดยอด Khwaeng Talat Yot แขวงบวรนิเวศ Khwaeng Bowon Niwet แขวงบำงขุนพรหม Khwaeng Bang Khun Phrom แขวงบ้ำนพำนถม Khwaeng Ban Phan Thom แขวงพระบรมมหำรำชวัง Khwaeng Phra Borom Maha Ratchawang แขวงวังบูรพำภิรมย์ Khwaeng Wang Burapha Phirom แขวงวัดรำชบพิธ Khwaeng Wat Ratchabophit แขวงวัดสำมพระยำ Khwaeng Wat Sam Phraya แขวงศำลเจ้ำพ่อเสือ Khwaeng San Chao Pho Suea แขวงส ำรำญรำษฎร์ Khwaeng Samran Rat แขวงเสำชิงช้ำ Khwaeng Sao Chingcha กรุงเทพมหำนคร เขตคลองเตย Khet Khlong Toei KRUNG THEP MAHA แขวงคลองตัน Khwaeng Khlong Tan NAKHON (BANGKOK) แขวงคลองเตย Khwaeng Khlong Toei แขวงพระโขนง Khwaeng Phra Khanong กรุงเทพมหำนคร เขตคลองสำน Khet Khlong San แขวงคลองต้นไทร Khwaeng Khlong Ton Sai แขวงคลองสำน Khwaeng Khlong San แขวงบำงล ำพูล่ำง Khwaeng Bang Lamphu Lang แขวงสมเด็จเจ้ำพระยำ Khwaeng Somdet Chao Phraya กรุงเทพมหำนคร เขตคลองสำมวำ Khet Khlong Sam Wa แขวงทรำยกองดิน Khwaeng Sai Kong Din แขวงทรำยกองดินใต้ Khwaeng Sai Kong Din Tai แขวงบำงชัน Khwaeng Bang Chan แขวงสำมวำตะวันตก Khwaeng Sam Wa Tawan Tok แขวงสำมวำตะวันออก Khwaeng Sam Wa Tawan Ok กรุงเทพมหำนคร เขตคันนำยำว Khet Khan Na Yao ส ำนักงำนรำชบัณฑิตยสภำ ข้อมูล ณ วันที่ ๒๒ กุมภำพันธ์ ๒๕๖๐ ๒ แขวงคันนำยำว Khwaeng Khan Na Yao แขวงรำมอินทรำ Khwaeng Ram Inthra กรุงเทพมหำนคร เขตจตุจักร Khet Chatuchak แขวงจตุจักร Khwaeng Chatuchak แขวงจอมพล Khwaeng Chom Phon แขวงจันทรเกษม Khwaeng Chan Kasem แขวงลำดยำว Khwaeng Lat Yao แขวงเสนำนิคม -

The Transport Trend of Thailand and Malaysia

Executive Summary Report The Potential Assessment and Readiness of Transport Infrastructure and Services in Thailand for ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Content Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Rationales 1 1.2 Objectives of Study 1 1.3 Scopes of Study 2 1.4 Methodology of Study 4 2. Current Status of Thailand Transport System in Line with Transport Agreement of ASEAN Community 2.1 Master Plan and Agreement on Transport System in ASEAN 5 2.2 Major Transport Systems for ASEAN Economic Community 7 2.2.1 ASEAN Highway Network 7 2.2.2 Major Railway Network for ASEAN Economic Community 9 2.2.3 Main Land Border Passes for ASEAN Economic Community 10 2.2.4 Main Ports for ASEAN Economic Community 11 2.2.5 Main Airports for ASEAN Economic Community 12 2.3 Efficiency of Current Transport System for ASEAN Economic Community 12 3. Performance of Thailand Economy and Transport Trend after the Beginning of ASEAN Economic Community 3.1 Factors Affecting Cross-Border Trade and Transit 14 3.2 Economic Development for Production Base Thriving in Thailand 15 3.2.1 The analysis of International Economic and Trade of Thailand and ASEAN 15 3.2.2 Major Production Bases and Commodity Flow of Prospect Products 16 3.2.3 Selection of Potential Industries to be the Common Production Bases of Thailand 17 and ASEAN 3.2.4 Current Situation of Targeted Industries 18 3.2.5 Linkage of Targeted Industries at Border Areas, Important Production Bases, 19 and Inner Domestic Areas TransConsult Co., Ltd. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi 2T Consulting and Management Co., Ltd. -

Europe-Africa Fixed Link Through the Strait of Gibraltar

ECOSOC Resolution 2007/16 Europe-Africa fixed link through the Strait of Gibraltar The Economic and Social Council, Recalling its resolutions 1982/57 of 30 July 1982, 1983/62 of 29 July 1983, 1984/75 of 27 July 1984, 1985/70 of 26 July 1985, 1987/69 of 8 July 1987, 1989/119 of 28 July 1989, 1991/74 of 26 July 1991, 1993/60 of 30 July 1993, 1995/48 of 27 July 1995, 1997/48 of 22 July 1997, 1999/37 of 28 July 1999, 2001/29 of 26 July 2001, 2003/52 of 24 July 2003 and 2005/34 of 26 July 2005, Referring to resolution 912 (1989), adopted on 1 February 1989 by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe,1 regarding measures to encourage the construction of a major traffic artery in south-western Europe and to study thoroughly the possibility of a fixed link through the Strait of Gibraltar, Referring also to the Declaration and work programme adopted at the Euro -Mediterranean Ministerial Conference, held in Barcelona, Spain, in November 1995 and aimed at connecting the Mediterranean transport networks to the trans-European network so as to ensure their interoperability, Referring fu rther to the plan of action adopted at the Summit marking the tenth anniversary of the Euro -Mediterranean Partnership, held in Barcelona in November 2005, which encouraged the adoption, at the first Euro -Mediterranean Ministerial Conference on Transport, held in Marrakech, Morocco, on 15 December 2005, of recommendations for furthering cooperation in the field of transport, Referring to the Lisbon Declaration adopted at the Conference on Transport in the