Tourism Discourse: Languages and Banal Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

<全文>Japan Review : No.34

<全文>Japan review : No.34 journal or Japan review : Journal of the International publication title Research Center for Japanese Studies volume 34 year 2019-12 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1368/00007405/ 2019 PRINT EDITION: ISSN 0915-0986 ONLINE EDITION: ISSN 2434-3129 34 NUMBER 34 2019 JAPAN REVIEWJAPAN japan review J OURNAL OF CONTENTS THE I NTERNATIONAL Gerald GROEMER A Retiree’s Chat (Shin’ya meidan): The Recollections of the.\ǀND3RHW+H]XWVX7ǀVDNX R. Keller KIMBROUGH Pushing Filial Piety: The Twenty-Four Filial ExemplarsDQGDQ2VDND3XEOLVKHU¶V³%HQH¿FLDO%RRNVIRU:RPHQ´ R. Keller KIMBROUGH Translation: The Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars R 0,85$7DNDVKL ESEARCH 7KH)LOLDO3LHW\0RXQWDLQ.DQQR+DFKLUǀDQG7KH7KUHH7HDFKLQJV Ruselle MEADE Juvenile Science and the Japanese Nation: 6KǀQHQ¶HQDQGWKH&XOWLYDWLRQRI6FLHQWL¿F6XEMHFWV C ,66(<ǀNR ENTER 5HYLVLWLQJ7VXGD6ǀNLFKLLQ3RVWZDU-DSDQ³0LVXQGHUVWDQGLQJV´DQGWKH+LVWRULFDO)DFWVRIWKH.LNL 0DWWKHZ/$5.,1* 'HDWKDQGWKH3URVSHFWVRI8QL¿FDWLRQNihonga’s3RVWZDU5DSSURFKHPHQWVZLWK<ǀJD FOR &KXQ:D&+$1 J )UDFWXULQJ5HDOLWLHV6WDJLQJ%XGGKLVW$UWLQ'RPRQ.HQ¶V3KRWRERRN0XUǀML(1954) APANESE %22.5(9,(:6 COVER IMAGE: S *RVRNXLVKLNLVKLNL]X御即位式々図. TUDIES (In *RVRNXLGDLMǀVDLWDLWHQ]XDQ7DLVKǀQREX御即位大甞祭大典図案 大正之部, E\6KLPRPXUD7DPDKLUR 下村玉廣. 8QVǀGǀ © 2019 by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Please note that the contents of Japan Review may not be used or reproduced without the written permis- sion of the Editor, except for short quotations in scholarly publications in which quoted material is duly attributed to the author(s) and Japan Review. Japan Review Number 34, December 2019 Published by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies 3-2 Goryo Oeyama-cho, Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto 610-1192, Japan Tel. 075-335-2210 Fax 075-335-2043 Print edition: ISSN 0915-0986 Online edition: ISSN 2434-3129 japan review Journal of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies Number 34 2019 About the Journal Japan Review is a refereed journal published annually by the International Research Center for Japanese Studies since 1990. -

CAPSTONE 19-4 Indo-Pacific Field Study

CAPSTONE 19-4 Indo-Pacific Field Study Subject Page Combatant Command ................................................ 3 New Zealand .............................................................. 53 India ........................................................................... 123 China .......................................................................... 189 National Security Strategy .......................................... 267 National Defense Strategy ......................................... 319 Charting a Course, Chapter 9 (Asia Pacific) .............. 333 1 This page intentionally blank 2 U.S. INDO-PACIFIC Command Subject Page Admiral Philip S. Davidson ....................................... 4 USINDOPACOM History .......................................... 7 USINDOPACOM AOR ............................................. 9 2019 Posture Statement .......................................... 11 3 Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip S. Davidson, U.S. Navy Photos Admiral Philip S. Davidson (Photo by File Photo) Adm. Phil Davidson is the 25th Commander of United States Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM), America’s oldest and largest military combatant command, based in Hawai’i. USINDOPACOM includes 380,000 Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, Airmen, Coast Guardsmen and Department of Defense civilians and is responsible for all U.S. military activities in the Indo-Pacific, covering 36 nations, 14 time zones, and more than 50 percent of the world’s population. Prior to becoming CDRUSINDOPACOM on May 30, 2018, he served as -

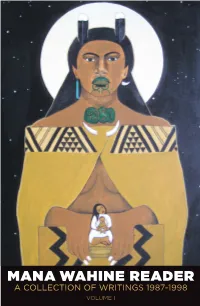

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

A Long-Forgotten Art”: Two M Ori Flutes in the Peabody Essex Museum

Lucy Mackintosh “A Long-Forgotten Art”: Two M ori Flutes in the Peabody Essex Museum Already we are boldly launched upon the deep, but soon we shall be lost in its unshored, harborless immensities. Herman Melville, 18511 In May 1807, Captain William Richardson and the crew of the Eliza sailed into the harbor at Salem, Massachusetts, after an absence of two years. The Eliza, laden with luxury goods from Canton, docked at one of the dozens of wharfs lining the harbor, alongside other trading vessels recently returned from the East Indies and China. But while most trading captains had followed the well-established trade routes to the East, Richardson had taken a longer, less familiar route, around the bottom of Australia and into Oceania. In the cargo hold of the Eliza, among the silk, cotton, tea, porcelain, and spices, lay a collec- tion of objects that Richardson had acquired on the journey. His collection, now held in the Peabody Essex Museum, contains a number of early, significant, and impressive Māori objects from New Zealand, including a pare (door lintel), papahou (treasure box), 1 2 Pūtōrino (flute), n.d. and a shark-tooth knife. But it is two small, delicate flutes that have Wood, 16 ¼ × 1 ½ in. caught and held my attention. (41.2 × 4 cm). Peabody Traders such as Richardson were among the first Americans Essex Museum, Salem, to enter the Pacific and exchange goods, objects, and ideas with Massachusetts. Gift of Captain William Polynesians, yet little is known about these early commercial voyages, Richardson, 1807, E5515. which were not as well documented as scientific expeditions to the 26 27 Pacific.3 The early experiences of these people from different worlds, separated by the vast Pacific Ocean and encountering each other for the first time, have largely vanished. -

Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender

Myths of Hakko Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Teshima, Taeko Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 21:55:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194943 MYTHS OF HAKKŌ ICHIU: NATIONALISM, LIMINALITY, AND GENDER IN OFFICIAL CEREMONIES OF MODERN JAPAN by Taeko Teshima ______________________ Copyright © Taeko Teshima 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Taeko Teshima entitled Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Barbara A. Babcock _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Philip Gabriel _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Susan Hardy Aiken Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Te Kawa Waiora Literature Review

Wairoa River Literature Review Te Kawa Waiora Working Paper 1 DATE 9 April 2021 BY Robyn Kāmira Paua Interface Ltd ON BEHALF OF Reconnecting Northland FOR Waimā, Waitai, Waiora Literature Review Te Kawa Waiora 9 April 2021 | Robyn Kāmira, Paua Interface Ltd ©Reconnecting Northland, 2021 Reconnecting Northland — Whenua ora, wai ora, tangata ora Literature Review Te Kawa Waiora 9 April 2021 | Robyn Kāmira, Paua Interface Ltd Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 This literature review . .6 1.2 Unique circumstances in 2020 . .7 1.3 Interesting examples . .8 1.4 The author. .8 2 Scope 9 2.1 Geographical scope . .9 2.2 Literature scope . 11 2.3 Key writers . 12 2.4 Māori writers and informants . 12 2.4.1 Hongi, Hāre aka Henry Matthew Stowell (1859-1944) . 12 2.4.2 Kāmira, Tākou (Himiona Tūpākihi) (~1876/7-1953) . .12 2.4.3 Kena, Paraone (Brown) (~1880?-1937) (informant) . 13 2.4.4 Marsden, Māori (1924-1993) . 13 2.4.5 Parore, Louis Wellington (1888-1953) (informant) . 13 2.4.6 Pene Hāre, Ngākuru (Te Wao) (1858-195?) . 14 2.4.7 Taonui, Aperahama aka Abraham Taonui (~1816-1882) . 14 2.5 European writers . 15 2.5.1 Buller, Rev. James (1812-1884) . .15 2.5.2 Cowan, James (1870-1943) . 15 2.5.3 Dieffenbach, Ernest (1811-1855) . .15 2.5.4 Graham, George Samuel (1874-1952) . 16 2.5.5 Halfpenny, Cyril James (1897-1927) . 16 2.5.6 Keene, Florence Myrtle QSM (1908-1988). .17 2.5.7 Polack, Joel Samuel (1807-1882) . 17 2.5.8 Smith, Stephenson Percy (1840-1922). -

Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for Staff Working in Pacific Communities Tropic of Cancer Tropique Du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS

Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for staff working in Pacific communities Tropic of Cancer Tropique du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS GUAM MARSHALL PALAU ISLANDS BELAU Pacic Ocean FEDERATED STATES Océan Pacifique OF MICRONESIA PAPUA NEW GUINEA KIRIBATI NAURU KIRIBATI KIRIBATI TUVALU SOLOMON TOKELAU ISLANDS COOK WALLIS & SAMOA ISLANDS FUTUNA AMERICA SAMOA VANUATU NEW FRENCH CALEDONIA FIJI NIUE POLYNESIA TONGA PITCAIRN ISLANDS AUSTRALIA RAPA NUI/ NORFOLK EASTER ISLAND ISLAND Tasman Sea Mer De Tasman AOTEAROA/ NEW ZEALAND Tropic of Cancer Tropique du Cancer HAWAII NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS GUAM MARSHALL PALAU ISLANDS BELAU Pacic Ocean FEDERATED STATES Océan Pacifique OF MICRONESIA PAPUA NEW GUINEA KIRIBATI NAURU KIRIBATI KIRIBATI TUVALU SOLOMON TOKELAU ISLANDS COOK WALLIS & SAMOA ISLANDS FUTUNA AMERICA SAMOA VANUATU NEW FRENCH CALEDONIA FIJI NIUE POLYNESIA TONGA PITCAIRN ISLANDS AUSTRALIA RAPA NUI/ NORFOLK EASTER ISLAND ISLAND Tasman Sea Mer De Tasman AOTEAROA/ NEW ZEALAND Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific Guidelines for staff working in Pacific communities Noumea, New Caledonia, 2020 Look out for these symbols for quick identification of areas of interest. Leadership and Protocol Daily Life Background Religion Protocol Gender Ceremonies Dress Welcoming ceremonies In the home Farewell ceremonies Out and about Kava ceremonies Greetings Other ceremonies Meals © Pacific Community (SPC) 2020 All rights for commercial/for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial/for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. -

The Reclamation of Culture Movement and NAIITS: an Indigenous Learning Community

ABSTRACT A Gifting of Sweetgrass: The Reclamation of Culture Movement and NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community Wendy L. Peterson In the mid-twentieth century the reclamation of Indigenous cultures, outlawed and otherwise suppressed through colonization, spread throughout New Zealand, United States, Canada, and elsewhere. Variously labelled as retraditionalization, revitalization, reclamation, and renaissance, it found expression in political demonstrations, public inquiries, litigation, art, music, and resistance literature. This dissertation traces the marginalization of First Peoples in their homelands triggered by the Great European Migration. Discouraged by the state of Indigenous churches and lack of discipleship, Indigenous Followers of Jesus [IFJ] joined in the reclamation of Indigenous self-identity through contextualizing the gospel and Christian culture as a means of healing social and spiritual realities. What began as local conversations grew to regional and global dialogues, resulting in a unique form of revitalization—the Reclamation of Culture Movement [ROCM]. The birth of the global ROCM is traced primarily to the Māori-led World Christian Gathering on Indigenous Peoples (1996). Employing Social Networking Theory, this work reveals the development of this movement through the global, regional, and local diffusion of the educational innovation first called the North American Institute for Theological Studies — now simply NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community. Providing a unique educational innovation for Aboriginal, -

Heuer 1966 R.Pdf

RULES ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII NOV. 8, 1955 WITH REGARD TO THE REPRODUCTION OF GRADUATE THESES (a) No person or corporation may publish or reproduce in any manner, without the consent of the Graduate School Council, a graduate thesis which has been submitted to the University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree. (b) No individual or corporation or other organization may publish quotations or excerpts from a graduate thesis without the consent of the author and of the Graduate School Council. MAORI WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL FAMILY AND TRIBAL LIFE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY JUNE 1966 By Berys N. Rose Heuer Thesis Committee: Katharine Luomala, Chairman Robert R. Jay Charles E. Osgood 677556 7? ,r*4 We certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthro pology. THESIS COMMITTEE Q — € Chairman v V c-r // U- 13*^ CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The Maori people about whom this thesis is written are xhe original Polynesian inhabitants of New Zealand, to which they Journeyed from a legendary tropical Hawaiki several cen turies ago. Canoe legends, at present being re-evaluated, and telling of Journeys from Hawaiki, have been utilized to date a major migration to the islands in the mid-fourteenth century, although its importance appears somewhat exaggerated. -

THE RISHUKYO: a Translation And

THE RISHUKYO: A Translation and Commentary in the Light of Modern Japanese (Post-Meiji) Scholarship by Ian ASTLEY Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of PhD The University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies October 1987 ABSTRACT This thesis is a translation of and commentary on the Tantric Buddh- ist Master Amoghavajra (705-74)'s Li-clki Ching gag (Japanese: Rishuky5, TaishO: 243), the Prajparamita in 150 Verses. Whilst there are some remarks of a historical and text-critical nature, the primary concern is with the text as a religious document, in the context of the scholarship and practice of the modern Japanese Shingon Sect. The Stara occupies a central position in this sect, being an integral part in its daily worship and in the academic and practical training of its priests. The Rishuky5 is extant in ten versions: a Sanskrit/Khotanese fragment (?150 verses), a Tibetan 150-verse version and six Chinese versions, one of which is a lengthy, so-called Extended Version. This last is paral- lelled by two Extended Versions in Tibetan, and, although an examination of the Tibetan sources lies outwith the scope of this study, the thesis sketches some of the possibilities for historical research into the Buddhist Tantric tradition in Central and East Asia which these three longer recensions open up. The Chinese versions -beginning with HsUan- tsang's (T.220(10))- show varying degrees of esoteric influence. This fact has significance for our understanding of Amoghavajra's version, which is a well co-ordinated ritual text. The systematic philosophical and symbolic expression of traditional Buddhist teachings which is inherent in Tantric ritual intent is the focus of this thesis. -

The Island of Alameda Has Been Home to Many Amazing and Famous People Through- out Its Long and Storied History. One of the Most

I S S U E N U m b E r 2 • A P r IL 2 0 2 0 The team poses for a portrait on the Alameda Taiiku Kai ballfield (known as the ATK Diamond) located at Clement Avenue and Walnut Street. They proudly display the ATK diamond logo on their jerseys. Japanese men built the field and in the spring they would gather to trim weeds to prepare for the upcoming season. Masted ships and wooden towers can be seen along the estuary. Images: John Towata, Jr. he island of alameda commerce with close to 900 first and Mas (Fred) Nakano, who played for Thas been home to many second generation Japanese Americans. the Alameda Taiiku Kai (ATK) team amazing and famous people through- This area was pridefully referred to for many years. Mr. Nakano explained out its long and storied history. One as Japantown. that Alameda Taiiku translated to of the most important and influential Two integral landmarks in “J-town” “Alameda Athletic Club.” groups of people has been the were the Buddhist Temple and Alameda “The roots of the ATK baseball Japanese American community Methodist South Church; two different team go back to 1913, when a team whose culture, dedication, and denominations, but one dynamic was founded by a group of Issei (first resiliency have been truly inspiring. culture who would come together generation) who brought their love In the early part of the 20th century, for “America’s pastime”...baseball! of baseball from Japan. These players Alameda was home to a unique and One of the Alameda baseball eventually formed the nucleus of flourishing region of culture and pioneers was Pacific Avenue resident Continued on page 2 .