The Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A'v':;:':It''iislili'i» -"^Ppi9"^A

-"^pPi 9"^ A ;Jlii'i> •• "' •% ' .V ( . i i''Yt« '-f,'I'1'' a'v':;:':i t''iiSlili'i» (kJ p. Throokmorton, "Thirty-threa Centuries under the Sea," National GeoKraphio, Llay 1960 (Vol.117, no.5), pp.682-703. x- . 5ed on a parent's mbling insect wings he adult's face. |to the Other, Free Ride scus fry instmc- melike secretion es. Microscopic •" V:k coating comes the epidermis. Fi a nonbreeding k-dwelling Sym- pliysodou soon cognize its owner. But if disturbed, the captive dashes madly about the aquarium and may even kill itself by banging its nose against the glass. Fish fanciers pay up to $10 for a young discus; mated pairs sell for as much as $350. 681 trolled by hormones, as is the milk production of a mammalian female. Among vertebrates, this "lactation" of both male and female is possibly unique. Un til research explains the full significance of the phenomenon, the discus—the fish that "nurses" its young—stands as a small but arresting biological wonder. W' •, * 1 y. 4JJmik •• Piggyback passengers feed on a parent's V secreted "milk." Fins resembling insect wings lend a whiskered look to the adult's face. Darting From One Parent to the Other, Babies Gain Lunch and a Free Ride As soon as they can swim, discus fry instinc tively begin to feed on a slimelike secretion that covers the parents' bodies. Microscopic examination shows that this coating comes from large mucous cells in the epidermis. Smaller cells on the body of a nonbreeding discus appear less productive. -

La Chasse Aux Trésors Subaquatiques. Portait D'une Industrie Marginale À L

Université de Montréal La chasse aux trésors subaquatiques. Portait d’une industrie marginale à l’ère de l’internet Par Stéphanie Courchesne Département d’anthropologie Faculté des Arts et des Sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des Arts et des Sciences En vue de l’obtention du grade de M. Sc. En Anthropologie Option Archéologie Décembre 2011 © Stéphanie Courchesne, 2011 ii IDENTIFICATION DU JURY Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales Ce mémoire intitulé : La chasse aux trésors subaquatiques : Portrait d’une industrie marginale à l’ère de l’internet Présenté par : Stéphanie Courchesne a été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Adrian Burke président-rapporteur Brad Loewen directeur de recherche Pierre Desrosiers membre du jury iii Résumé et mots-clés français En marge des recherches archéologiques traditionnelles, nous retrouvons aujourd’hui des compagnies privées qui contractent des accords et obtiennent des permis leur donnant le droit de prélever des objets à des fins lucratives sur les vestiges archéologiques submergés. Ces pratiques commerciales causent une controverse vive et enflammée au sein du monde archéologique. Le principal point de litiges concerne la mise en vente des objets extraits lors de fouille. La mise en marché du patrimoine archéologique éveille les fibres protectionnistes. Cela incite certains organismes à poser des gestes pour la protection du patrimoine. C’est le cas pour l’UNESCO qui fait la promotion depuis 2001 d’une Convention pour la protection du patrimoine submergé. Malgré tous les arguments à l’encontre des compagnies de « chasse aux trésors », cette Convention est loin de faire l’unanimité des gouvernements à travers le monde, qui ne semblent pas prêts à rendre ces pratiques illégales. -

Raisign the Dead: Improving the Recovery and Management of Historic Shipwrecks, 5 Ocean & Coastal L.J

Ocean and Coastal Law Journal Volume 5 | Number 2 Article 5 2000 Raisign The eD ad: Improving The Recovery And Management Of Historic Shipwrecks Jeffrey T. Scrimo University of Maine School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj Recommended Citation Jeffrey T. Scrimo, Raisign The Dead: Improving The Recovery And Management Of Historic Shipwrecks, 5 Ocean & Coastal L.J. (2000). Available at: http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj/vol5/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ocean and Coastal Law Journal by an authorized administrator of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RAISING THE DEAD: IMPROVING THE RECOVERY AND MANAGEMENT OF HISTORIC SHIPWRECKS Jeffrey T Scrimo* I. INTRODUCTION Dead men tell no tales at the bottom of the sea. For thousands of years, this truth remained unalterable; but now, the rapid development of underwater technology is prying open the once impenetrable realm of Davy Jones's locker. This technology gives us access to the seas darkest secrets, and opens new windows to our past. Indeed, what once only lingered at the edge of dreams is now a reality. The sea has stubbornly begun to yield its treasures to those brave enough to search. In recent years, enterprising adventurers have reclaimed pirates' gold,' discovered the riches of past empires,' and peered23 into the ironic serenity of disaster.3 Bringing these * University of Maine School of Law, Class of 2000. -

Conservation of Underwater Archaeological Organic Materials)

UNIVERSIDADE AUTÓNOMA DE LISBOA LUIS DE CAMÕES Departamento de História Tese de Doutoramento em História Conservação de Materiais Orgânicos Arqueológicos Subaquáticos (Conservation of Underwater Archaeological Organic Materials) Tese apresentada para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em História Orientador: Adolfo Silveira Martins Co-orientador: Donny L. Hamilton Doutoranda: Andreia Ribeiro Romão Veliça Machado Junho, 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here would not have been possible without the help and collaboration of a group of people I would like to thank. To start with, the members of my committee, Prof. Adolfo Silveira Martins and Prof. Donny L. Hamilton. They kindly accepted me as their student and since then have been most supportive and helpful. Enough cannot be said about the help I received from Helen Dewolf, at the Conservation Research Laboratory, and also Dr. Wayne Smith. They were willing to teach me everything that they knew, get me any supplies and samples that I needed and they were always there to check my work and to guide me when needed. Deep gratitude is reserved for Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH / BD / 49007 / 2008), to Dr. Jorge Campos of the Câmara Municipal de Portimão , without whose interest in supporting me, this research would not have been accomplished. A thank you to Madalena Mira, Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa Library Director, and to Doctors Mike Pendleton and Ann Ellis from the Microscopy & Imaging Center, at Texas A&M. Another word of appreciation to Dr. Adolfo Miguel Martins and Dr. João Coelho from DANS, for the enlightening conversations and help during the research. -

Third Quarter 2016 • Volume 24 • Number 88

The Journal of Diving History, Volume 24, Issue 3 (Number 88), 2016 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 04/10/2021 13:18:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35937 Third Quarter 2016 • Volume 24 • Number 88 The Anthony and Yvonne Pardoe Collection Auction | Bob Kendall’s Macro Camera | Under The Sea on a Glider Conshelf: The Story of Cousteau and his future vision Continental Shelf Stations IV, V, and VI SAVE THE DATE 25th Anniversary Conference 1992 - 2017 September 15 - 16, 2017 Santa Barbara Maritime Museum DEMA 2016 WEEK EVENTS honoring NOGI historical recipients: diving society PIONEER Stephen Frink award (arts) TO BE PRESENTED Mike Cochran TO (science) Jack W. Lavanchy (posthumously) Bob Croft (sports/ education) and presenting the ZALE PARRY Bonnie Toth (distinguished scholarship service) to Angela Zepp Hardy Jones (environment) THE 56th ANNUAL NOGI AWARDS GALA the academy of underwater arts and sciences november 17, 2016 • 6 pm Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino RESERVATIONS & INFORMATION: www.auas-nogi.org/gala.html Join Us at the DAN Party Attend the DAN Party at DEMA to enjoy an evening of conversation, drinks and fun. As your dive safety organization, we know how much you do to keep your divers safe, and we would like to raise a glass to all of the individuals who work year-round to promote dive safety. Date & Time Location Wednesday, November 16th Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino 6:30pm - 8:30pm Ballroom B 3000 Paradise Road Las Vegas, NV DAN.org Third Quarter 2016, Volume 24, Number 88 The Journal of Diving History 1 DAN_DEMA_HDS_ad.indd 1 10/7/16 5:14 PM THE JOURNAL OF DIVING HISTORY THIRD QUARTER 2016 • VOLUME 24 • NUMBER 88 ISSN 1094-4516 FEATURES The Lost Treasure of Captain Sorcho The Anthony and Yvonne Pardoe By Jerry Kuntz Collection Auction 9 The career of Captain Louis Sorcho has been featured numerous times in 28 By Leslie Leaney prior issues of the Journal. -

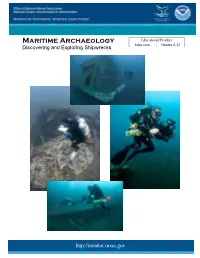

Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Educational Product Maritime Archaeology Educators Grades 6-12 Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Acknowledgement This educator guide was developed by NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. This guide is in the public domain and cannot be used for commercial purposes. Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction, without alteration, of this guide on the condition its source is acknowledged. When reproducing this guide or any portion of it, please cite NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary as the source, and provide the following URL for more information: http://monitor.noaa.gov/education. If you have any questions or need additional information, email [email protected]. Cover Photo: All photos were taken off North Carolina’s coast as maritime archaeologists surveyed World War II shipwrecks during NOAA’s Battle of the Atlantic Expeditions. Clockwise: E.M. Clark, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Dixie Arrow, Photo: Greg McFall, NOAA; Manuela, Photo: Joseph Hoyt, NOAA; Keshena, Photo: NOAA Inside Cover Photo: USS Monitor drawing, Courtesy Joe Hines http://monitor.noaa.gov Monitor National Marine Sanctuary: Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and Exploring Shipwrecks Monitor National Marine Sanctuary Maritime Archaeology—Discovering and exploring Shipwrecks _____________________________________________________________________ An Educator -

DEGUWA Annual Meeting on Underwater Archaeology in POSEIDON’S REALM XXVI Safety and Waterways

DEGUWA Annual Meeting on Underwater Archaeology IN POSEIDON’S REALM XXVI Safety and Waterways from May 8, 2021 through May 9, 2021 Online Conference in Cooperation with the TRANSMARE Institut of the University of Trier Under the Patronage of the President Prof. Dr. Michael Jäckel VICTORIA and LUSORIA RHENANA at joint patrol on the “Haltener See” Photo: transmare institut Stand: 19.04.2021 Organizing Committee: Julian Heinz , Ralph Kunz, Katharina Meyer -Regenhardt, Georg Osterfeld, Thomas Reiser, Christoph Schäfer, Peter Winterstein Scientific Committee: Ronald Bockius, Christoph Eger, Winfried Held, Marcus Nenninger, Christoph Schäfer, Peter Winterstein Executive Committee: Julian Heinz , Ralph Kunz, Katharina Meyer -Regenhardt, Patrick Reinard, Christian Rollinger, Christoph Schäfer, Birgit Sommer, Piotr Wozniczka, Page 2 | 25 Program Saturday, May 8, 2021 Lectures I Instructions Chair Schäfer, Christoph Time: 09.15-09.30 a.m. Opening and Greetings Winfried Held, President of the DEGUWA Michael Jäckel, President of the University Trier Time: 09.30-10.30 a.m. Spanos, Stefanos Schiffsdarstellungen auf Mykenischer Keramik. Die seltsame Darstellung eines Schiffswracks von Koukounaries auf Paros Coffee break Time: 10.30-11.00 a.m. Lectures I (cont.) Chair: Reiser, Thomas Time: 11.00-12.30 p.m. Reich, Alexander Terra et aqua. - Untersuchung der Hafenbecken Milets unter nautischen Gesichtspunkten Auriemma, Rita et al. The underwater archaeology tells of Salento: Recent research in the Adriatic and Ionian seas Auriemma, Rita et al. Shipwrecks stories in a “trap bay”: Research and valorization in Torre S. Sabina (Brindisi, Italy) Discussion Time: 12.30-1.00 p.m. Lunch break Time: 1.00-2.30 p.m. -

George F. Bass Underwater Archaeology Papers 1054 Finding Aid Prepared by Jody Rodgers

George F. Bass Underwater Archaeology papers 1054 Finding aid prepared by Jody Rodgers. Last updated on March 02, 2017. University of Pennsylvania, Penn Museum Archives 3/14/11 George F. Bass Underwater Archaeology papers Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 8 Correspondence.......................................................................................................................................8 Expedition records............................................................................................................................... -

Maritime Archaeology: Challenges for the New Millennium

1 World Archaeological Congress 4 University of Cape Town 10th - 14th January 1999 Symposium: Maritime archaeology: challenges for the new millennium Underwater Archaeology in Greece: Past, Present, and Future Eleftheria Mantzouka-Syson Greece’s importance and role in the heavy maritime traffic plowing the Eastern Mediterranean Sea since times immemorial is well known. The country is surrounded by and shares with her neighboring countries three major bodies of water, the Ionian, the Aegean, and the Libyan Seas. These waters have become the receptacle of an amazing number of human remains, which are part of one of the most significant chapters of the Greek history: her maritime cultural heritage. This heritage has also been a part of other peoples’ history and culture interacting in numerous ways across this blue whimsical sea. And that is what enhances the significance of Greece’s maritime history and underwater cultural heritage: her multi-faceted international character that demands intense study and active protection. The Greek archaeological legislation in relation to underwater heritage In Greece, awareness about the importance of and protection for the national cultural heritage on land and its submerged counterpart came as early as the emergence and formation of the new independent state in the late 1820s-early 1830s. In 1828, Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias issued the order 2400/12.5.1828 addressed to 2 the temporary Commissaries throughout the Aegean Sea, which forbade the export of any archaeological remains from the Greek State.i An official provision, in regards to the protection of antiquities found underwater, is embedded in the first comprehensive legal text of the national antiquities law of 1834 (10/22.5.1834). -

An Archaeological Argument for the Inapplicability of Admiralty Law in the Disposition of Historic Shipwrecks Terence P

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 26 | Issue 2 Article 6 2000 An Archaeological Argument for the Inapplicability of Admiralty Law in the Disposition of Historic Shipwrecks Terence P. McQuown Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation McQuown, Terence P. (2000) "An Archaeological Argument for the Inapplicability of Admiralty Law in the Disposition of Historic Shipwrecks," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 26: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol26/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law McQuown: An Archaeological Argument for the Inapplicability of Admiralty L AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL ARGUMENT FOR THE INAPPLICABILITY OF ADMIRALTY LAW IN THE DISPOSITION OF HISTORIC SHIPWRECKS Terence P. McQuownt I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 289 II. THE TRADITIONAL ANARCHY ................................................. 293 A. The Law of Salvage ...................................................... 295 B. The Law of Finds ......................................................... 299 III. A MODEST PROPOSAL ............................................................. 302 IV . CONCLUSION ......................................................................... -

The Value of Maritime Archaeological Heritage

THE VALUE OF MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF THE CULTURAL CAPITAL OF SHIPWRECKS IN THE GRAVEYARD OF THE ATLANTIC by Calvin H. Mires April 2014 Director of Dissertation: Dr. Nathan Richards Ph.D. Program in Coastal Resources Management Off the coast of North Carolina’s Outer Banks are the remains of ships spanning hundreds of years of history, architecture, technology, industry, and maritime culture. Potentially more than 2,000 ships have been lost in “The Graveyard of the Atlantic” due to a combination of natural and human factors. These shipwrecks are tangible artifacts to the past and constitute important archaeological resources. They also serve as dramatic links to North Carolina’s historic maritime heritage, helping to establish a sense of identity and place within American history. While those who work, live, or visit the Outer Banks and look out on the Graveyard of the Atlantic today have inherited a maritime heritage as rich and as historic as any in the United States, there is uncertainty regarding how they perceive and value the preservation of maritime heritage resources along the Outer Banks, specifically shipwrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic. This dissertation is an exploratory study that combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies from the fields of archaeology, economics, and sociology, by engaging different populations in a series of interviews and surveys. These activities are designed to understand and evaluate the public’s current perceptions and attitudes towards maritime archaeological heritage, to estimate its willingness to pay for preservation of shipwrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, and to provide baseline data for informing future preservation, public outreach, and education efforts. -

Maritime Archaeology in the 21St Century by James P

Maritime Archaeology in the 21st Century by James P. Delgado he art and science of archaeology is now more than a century old, and the practice of it underwater and in the maritime world spans about half that time, or some fifty-five years. While antiquarian interest in maritime finds dates to the nineteenth century, with discoveries of buried ships—either in land-filled harbors, or the famous disinterment of the Gokstad and Oseberg ship burials in what is now Norway— what lay under the seas awaited a new century. The 1900 discov- ery and recovery of a trove of ancient bronze statues from a first Tcentury BC shipwreck off the Greek Aegean island of Antiky- thera sparked interest in undersea exploration. The invention of SCUBA, along with a growth in the number of divers in the 1950s and 1960s, led to the birth of archaeology practiced under water as well as underwater archaeology. The first scientific excavation of a shipwreck in its entirety from the seabed took place in 1960 when George F. Bass and Peter Throckmorton, working with Honor Frost, Frédéric Dumas, Claude Duthuit and others raised the scattered remains of a Bronze Age wreck dating to around 1200 BC from the waters of Turkey’s Cape Gelidonya. institute of nautical archaeology institute of nautical In 1960, George Bass—often referred to as the Father of Underwa- ter Archaeology—and his colleague Peter Throckmorton led a team in a full archaeological excavation of a Bronze Age shipwreck off Cape Gelidonya in Turkey. (above) Bass and Throckmorton examine bronze ingots raised from the Gelidonya wreck site.