109 I. INTRODUCTION the Strategikon Is a Roman Military

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combat Motivation and Cohesion in the Age of Justinian by Conor Whately, University of Winnipeg

Combat Motivation and Cohesion in the Age of Justinian By Conor Whately, University of Winnipeg One topic that regularly recurs in the scholarship on modern warfare is combat cohesion and motivation. Many volumes have been published on these topics, and there is no sign that this interest might abate any time soon. That interest has only rarely filtered down to scholarship of the ancient and late antique worlds, however. 1 The sixth century is well suited to analyses of these issues given the abundance of varied and high quality evidence, despite the lack of attention given the subject by modern scholars. This chapter seeks to remedy this by offering an introduction to combat cohesion and motivation in the sixth century. It forms the second half of a two-part project on the subject, and the core this project is the evidence of Procopius. 2 Procopius describes more than thirty battles or sieges from the age of Justinian,3 and his battle narratives have been the subject of a good deal of research. 4 Yet there is much more work to do on sixth-century combat and our understanding Procopius’ value as a source for military history. By introducing the subject of combat cohesion and motivation in the sixth century, this paper seeks to move the discussion forward. 5 The first part of this paper will be concerned with motivation, and will explore the much discussed “ratio of fire” and its applicability in an ancient context, the presumed bellicosity of some soldiers that many of our sources hint at, and the role of fear in motivating soldiers to fight and to maintain their cohesion. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1 Institute of Archaeology Belgrade, Serbia 24. LIMES CONGRESS Serbia 02-09 September 2018 Belgrade - Viminacium BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER Institute of Archaeology Kneza Mihaila 35/IV 11000 Belgrade http://www.ai.ac.rs [email protected] Tel. +381 11 2637-191 EDITOR IN CHIEF Miomir Korać Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade EDITORS Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade Nemanja Mrđić Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade GRAPHIC DESIGN Nemanja Mrđić PRINTED BY DigitalArt Beograd PRINTED IN 500 copies ISBN 979-86-6439-039-2 4 CONGRESS COMMITTEES Scientific committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology Miroslav Vujović, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology Stefan Pop-Lazić, Institute of Archaeology Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology Nemanja Mrđić, Institute of Archaeology International Advisory Committee David Breeze, Durham University, Historic Scotland Rebecca Jones, Historic Environment Scotland Andreas Thiel, Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Esslingen Nigel Mills, Heritage Consultant, Interpretation, Strategic Planning, Sustainable Development Sebastian Sommer, Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Lydmil Vagalinski, National Archaeological Institute with Museum – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Mirjana Sanader, Odsjek za arheologiju Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Organization committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology -

Bullard Eva 2013 MA.Pdf

Marcomannia in the making. by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Eva Bullard 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Marcomannia in the making by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member During the last stages of the Marcommani Wars in the late second century A.D., Roman literary sources recorded that the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was planning to annex the Germanic territory of the Marcomannic and Quadic tribes. This work will propose that Marcus Aurelius was going to create a province called Marcomannia. The thesis will be supported by archaeological data originating from excavations in the Roman installation at Mušov, Moravia, Czech Republic. The investigation will examine the history of the non-Roman region beyond the northern Danubian frontier, the character of Roman occupation and creation of other Roman provinces on the Danube, and consult primary sources and modern research on the topic of Roman expansion and empire building during the principate. iv Table of Contents Supervisory Committee ..................................................................................................... -

Constantinopolitan Charioteers and Their Supporters

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2084-140X.01.08 Studia Ceranea 1, 2011, p. 127-142 Teresa Wolińska (Łódź) Constantinopolitan Charioteers and Their Supporters So engrossed were they in the wild passion that the entire city was filled with their voices and wild screaming. (...) Some perched higher behaving in decorously, others located in the market shouted at the horsemen, applauded them and screamed more than others.1 The above characteristics of the Byzantine supporters, recorded in the fourth century by the bishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, could as well, after minor adjustments, be applied to describe today’s football fans .Support in sport is certainly one of the oldest human passions. It is only the disciplines captivating audiences that change. In the ancient Roman Empire, bloody spectacles had the same role as today’s world league games – gladiatorial combat and fights withwild animals2. However, they were incompatible with Christian morality, and as such, they were gradually eliminated as the Christianization progressed3 .Their place was taken by hippodrome racing, particularly chariot racing . Residents of the imperial capital cheered the chariot drivers, whose colourful outfits signaled their membership in a particular circus faction . In the empire, there were four factions (demes), named after the colours of their outfits worn by runners and drivers representing them, the Blues, Greens, Whites and Reds4 .Each faction had 1 Joannes Chrysostomos, Homilia adversus eos qui ecclesia relicta ad circenses ludos et theatra transfugerunt, 1, [in:] PG, vol . LVI, col . 263 . 2 H .G . Saradi, The Byzantine City in the Sixth Century . Literary Images and Historical Reality, Athens 2006, p . -

VIVERE MILITARE EST from Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier Volume I

VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier Volume I BELGRADE 2018 VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY MONOGRAPHIES No. 68/1 VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier VOM LU E I Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER PROOFREADING Institute of Archaeology Dave Calcutt Kneza Mihaila 35/IV Ranko Bugarski 11000 Belgrade Jelena Vitezović http://www.ai.ac.rs Tamara Rodwell-Jovanović [email protected] Rajka Marinković Tel. +381 11 2637-191 GRAPHIC DESIGN MONOGRAPHIES 68/1 Nemanja Mrđić EDITOR IN CHIEF PRINTED BY Miomir Korać DigitalArt Beograd Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade PRINTED IN EDITORS 500 copies Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade COVER PAGE Nemanja Mrđić Tabula Traiana, Iron Gate Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade REVIEWERS EDITORiaL BOARD Diliana Angelova, Departments of History of Art Bojan Ðurić, University of Ljubljana, Faculty and History Berkeley University, Berkeley; Vesna of Arts, Ljubljana; Cristian Gazdac, Faculty of Dimitrijević, Faculty of Philosophy, University History and Philosophy University of Cluj-Napoca of Belgrade, Belgrade; Erik Hrnčiarik, Faculty of and Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford; Philosophy and Arts, Trnava University, Trnava; Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade; Kristina Jelinčić Vučković, Institute of Archaeology, Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade; Zagreb; Mario Novak, Institute for Anthropological Ioan Piso, Faculty of History and Philosophy Research, -

09. Ch. 6 Huitink-Rood

Histos Supplement ( ) – SUBORDINATE OFFICERS IN XENOPHON’S ANABASIS * Luuk Huitink and Tim Rood Abstract : This chapter focuses on Xenophon’s treatment of divisions within the command structure presented in the Anabasis , and in particular on three military positions that are briefly mentioned—the taxiarch, ὑποστράτηγος , and ὑπολόχαγος . Arguing against the prescriptive military hierarchies proposed in earlier scholarship, it suggests that ‘taxiarch’ should be understood fluidly and that the appearance of both the ὑποστράτηγος and the ὑπολόχαγος may be due to interpolation. The chapter also includes discussion of two types of comparative material: procedures for replacing dead, absent, or deposed generals at Athens and Sparta in the Classical period, and the lexical development of subordinate positions with the prefix ὑπο -. Keywords : Xenophon, Anabasis , subordinate commanders, taxiarch, ὑποστράτηγος , ὑπολόχαγος . enophon’s Anabasis has more often been broadly eulogised for its supposed depiction of the X democratic spirit of the Greek mercenaries whose adventures are recounted than analysed closely for the details it o?ers about the command structure of this ‘wandering republic’. 1 When Xenophon’s presentation of * References are to Xenophon’s Anabasis unless otherwise specified. Translations are adapted from the Loeb edition of Brownson and Dillery. We are grateful to Peter Rhodes for advice and to Simon Hornblower, Nick Stylianou, David Thomas, the editor, and the anonymous referee of Histos for comments on the whole article. Luuk Huitink’s work on this paper was made possible by ERC Grant Agreement n. B B (AncNar). 1 Krüger (E ) (‘civitatem peregrinantem’). On the command structure see Nussbaum (F) ‒E; Roy (F) EF‒; Lee ( F) ‒ , ‒ . -

Slavs and Avars (500–800)

chapter 4 East European Dark Ages: Slavs and Avars (500–800) In response to repeated raids into their lands “on the far side of the river” Danube, the Slavs, thought it over among themselves, and said: “These Romani, now that they have crossed over and found booty, will in the future not cease com- ing over against us, and so we will devise a plan against them.” And so, therefore, the Slavs, or Avars, took counsel, and on one occasion when the Romani had crossed over, they laid ambushes and attacked and defeat- ed them. The aforesaid Slavs took the Roman arms and the rest of their military insignia and crossed the river and came to the frontier pass, and when the Romani who were there saw them and beheld the standards and accouterments of their own men they thought they were their own men, and so, when the aforesaid Slavs reached the pass, they let them through. Once through, they instantly expelled the Romani and took pos- session of the aforesaid city of Salona. There they settled and thereafter began gradually to make plundering raids and destroyed the Romani who dwelt in the plains and on the higher ground and took possession of their lands.1 Thus described Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, in the mid-10th century, the migration of the Slavs from their lands to the Balkans. The story is placed chronologically “once upon a time,” at some point between the reigns of Emperors Diocletian, who brought the “Romani” to Dalmatia, and Heraclius. There is no reason to treat the story as a trustworthy historical account, but it is clear that it is meant to explain the particular situation of Salona and the former province of Dalmatia.2 No historian seems to have noticed so far that Emperor Constantine VII’s account is, after all, the only written testimony of 1 Constantine Porphyrogenitus, On the Administration of the Empire 29, pp. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405129992_6_ind.qxd 16/06/2009 12:11 Page 203 Index Acanthus, 130 Aetolian League, 162, 163, 166, Acarnanians, 137 178, 179 Achaea/Achaean(s), 31–2, 79, 123, Agamemnon, 51 160, 177 Agasicles (king of Sparta), 95 Achaean League: Agis IV and, agathoergoi, 174 166; as ally of Rome, 178–9; Age grades: see names of individual Cleomenes III and, 175; invasion grades of Laconia by, 177; Nabis and, Agesilaus (ephor), 166 178; as protector of perioecic Agesilaus II (king of Sparta), cities, 179; Sparta’s membership 135–47; at battle of Mantinea in, 15, 111, 179, 181–2 (362 B.C.E.), 146; campaign of, in Achaean War, 182 Asia Minor, 132–3, 136; capture acropolis, 130, 187–8, 192, 193, of Phlius by, 138; citizen training 194; see also Athena Chalcioecus, system and, 135; conspiracies sanctuary of after battle of Leuctra and, 144–5, Acrotatus (king of Sparta), 163, 158; conspiracy of Cinadon 164 and, 135–6; death of, 147; Acrotatus, 161 Epaminondas and, 142–3; Actium, battle of, 184 execution of women by, 168; Aegaleus, Mount, 65 foreign policy of, 132, 139–40, Aegiae (Laconian), 91 146–7; gift of, 101; helots and, Aegimius, 22 84; in Boeotia, 141; in Thessaly, Aegina (island)/Aeginetans: Delian 136; influence of, at Sparta, 142; League and,COPYRIGHTED 117; Lysander and, lameness MATERIAL of, 135; lance of, 189; 127, 129; pro-Persian party on, Life of, by Plutarch, 17; Lysander 59, 60; refugees from, 89 and, 12, 132–3; as mercenary, Aegospotami, battle of, 128, 130 146, 147; Phoebidas affair and, Aeimnestos, 69 102, 139; Spartan politics and, Aeolians, -

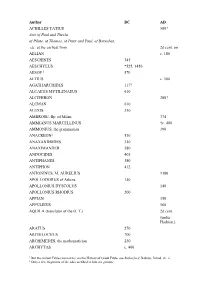

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Estancia News-Herald, 06-04-1914 J

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Estancia News, 1904-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-4-1914 Estancia News-Herald, 06-04-1914 J. A. Constant Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/estancia_news Recommended Citation Constant, J. A.. "Estancia News-Herald, 06-04-1914." (1914). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/estancia_news/121 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Estancia News, 1904-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTANCIA NEWS-HERAL- D New EsUblished 11)04 EBtancia, Herald KBtabliBhed 1908 Torrance County, New Mexico, Thursday, June 4, 1914 Volume X No. 31 and spent a few days visiting in Sunday E E LUCIA from Santa Rosa where IDLER DECIDES the vicinity. he has been teaching the past A great many people from Mc- Special Correspondence. eight months. FOR SALAS TO TEACHERS FOR THE VALLEY intosh, Estancia, Cedar Grove, A nice slow rain Sunday eve- V. I. Strickland was over from New Home and many other ning which was very encourag Albuquerque Monday, accom points attended the play at this ing and farmers are smiling over panied by two cattlemen who place. The State Board of r the garden and crop prospects, were looking at land here and Santa Fe, June 2 Judge Ed Education During the past week there Estancia, N. M. May 28, 1914. has conceded to val- Mrs. Chas. Clark spent a few Quite Estancia. -

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3 Sasanika Sources History of Menander the Guardsman (Menander Protector) was written at the end of the sixth century CE by a minor official of the Roman/Byzantine court. The original text is in Greek, but has survived only in a fragmentary form, quoted in compilations and other historical writings. The author, Menander, was a native of Constantinople, seemingly from a lowly class and initially himself not worthy of note. In a significant introductory passage, he courageously admits to having undertaken the writing of his History (’ st a) as a way of becoming more respectable and forging himself a career. He certainly was a contemporary and probably an acquaintance of the historian Theophylact Simocatta and worked within the same court of Emperor Maurice. His title of “Protector” seems to suggest a military position, but most scholars suspect that this was only an honorary title without any real responsibilities. Menander’s history claims to continue the work of Agathias and so starts from the date that Agathias left off, namely AD 557. His style of presentation, if not his actual writing style, are thus influenced by Agathias, although he seems much less partial than the former in presentation of the events. He seems to have had access to imperial archives and reports and consequently presents us with a seemingly accurate version of the events, although at time he might be exaggerating some of his facts. The following is R. C. Blockley’s English translation of the fragments 6.1-3 of Menander Protector’s History, which deals directly with the Sasanian-Roman peace treaty of 562 and provides us with much information about the details of negotiations that took place around this treaty.