Chpater Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combat Motivation and Cohesion in the Age of Justinian by Conor Whately, University of Winnipeg

Combat Motivation and Cohesion in the Age of Justinian By Conor Whately, University of Winnipeg One topic that regularly recurs in the scholarship on modern warfare is combat cohesion and motivation. Many volumes have been published on these topics, and there is no sign that this interest might abate any time soon. That interest has only rarely filtered down to scholarship of the ancient and late antique worlds, however. 1 The sixth century is well suited to analyses of these issues given the abundance of varied and high quality evidence, despite the lack of attention given the subject by modern scholars. This chapter seeks to remedy this by offering an introduction to combat cohesion and motivation in the sixth century. It forms the second half of a two-part project on the subject, and the core this project is the evidence of Procopius. 2 Procopius describes more than thirty battles or sieges from the age of Justinian,3 and his battle narratives have been the subject of a good deal of research. 4 Yet there is much more work to do on sixth-century combat and our understanding Procopius’ value as a source for military history. By introducing the subject of combat cohesion and motivation in the sixth century, this paper seeks to move the discussion forward. 5 The first part of this paper will be concerned with motivation, and will explore the much discussed “ratio of fire” and its applicability in an ancient context, the presumed bellicosity of some soldiers that many of our sources hint at, and the role of fear in motivating soldiers to fight and to maintain their cohesion. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

109 I. INTRODUCTION the Strategikon Is a Roman Military

A C T A AThe R SCTra HT egikonA E Oa S La SOource G I —C SlavA SC andA Ra varP SA… T H I C109 A VOL. LII, 2017 PL ISSN 0001-5229 ŁUKASZ Różycki THE STRATEGIKON AS A SOURCE — SLAVS AND AVARS IN THE EYES OF PSEUDO-MAURICE, CURRENT STATE OF RESEARCH AND FUTURE RESEARCH PERSPECTIVES ABSTRACT Ł. Różycki 2017. The Strategikon as a source — Slavs and Avars in the eyes of Pseudo-Maurice, current state of research and future research perspectives, AAC 52:109–131. The purpose of the piece The Strategikon as a source — Slavs and Avars in the eyes of Pseudo- Maurice, current state of research and future research perspectives is to demonstrate what the author of Strategikon knew about the Slavs and Avars and review the state of research on the chapter of the treatise that deals with these two barbarian ethnicities. As a side note to the de- scription of contemporary studies of Strategikon, the piece also lists promising areas of research, which have not yet received proper attention from scholars. K e y w o r d s: Migration Period; Early Middle Ages; Balkans; Byzantium; Strategicon; Strategikon; Emperor Maurice; Slavs; Avars Received: 15.03.2017; Revised: 30.07.2017; Revised: 19.10.2017; Revised: 29.10.2017; Accepted: 30.10.2017 I. INTRODUCTION The Strategikon is a Roman military treatise, written at the end of the 6th or the beginning of the 7th century. It is one of the seminal sources not only on East Roman military history but also on the Slavs, the Avars and other peoples neighboring the Empire at the onset of the Middle Ages. -

Constantinopolitan Charioteers and Their Supporters

http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2084-140X.01.08 Studia Ceranea 1, 2011, p. 127-142 Teresa Wolińska (Łódź) Constantinopolitan Charioteers and Their Supporters So engrossed were they in the wild passion that the entire city was filled with their voices and wild screaming. (...) Some perched higher behaving in decorously, others located in the market shouted at the horsemen, applauded them and screamed more than others.1 The above characteristics of the Byzantine supporters, recorded in the fourth century by the bishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, could as well, after minor adjustments, be applied to describe today’s football fans .Support in sport is certainly one of the oldest human passions. It is only the disciplines captivating audiences that change. In the ancient Roman Empire, bloody spectacles had the same role as today’s world league games – gladiatorial combat and fights withwild animals2. However, they were incompatible with Christian morality, and as such, they were gradually eliminated as the Christianization progressed3 .Their place was taken by hippodrome racing, particularly chariot racing . Residents of the imperial capital cheered the chariot drivers, whose colourful outfits signaled their membership in a particular circus faction . In the empire, there were four factions (demes), named after the colours of their outfits worn by runners and drivers representing them, the Blues, Greens, Whites and Reds4 .Each faction had 1 Joannes Chrysostomos, Homilia adversus eos qui ecclesia relicta ad circenses ludos et theatra transfugerunt, 1, [in:] PG, vol . LVI, col . 263 . 2 H .G . Saradi, The Byzantine City in the Sixth Century . Literary Images and Historical Reality, Athens 2006, p . -

Slavs and Avars (500–800)

chapter 4 East European Dark Ages: Slavs and Avars (500–800) In response to repeated raids into their lands “on the far side of the river” Danube, the Slavs, thought it over among themselves, and said: “These Romani, now that they have crossed over and found booty, will in the future not cease com- ing over against us, and so we will devise a plan against them.” And so, therefore, the Slavs, or Avars, took counsel, and on one occasion when the Romani had crossed over, they laid ambushes and attacked and defeat- ed them. The aforesaid Slavs took the Roman arms and the rest of their military insignia and crossed the river and came to the frontier pass, and when the Romani who were there saw them and beheld the standards and accouterments of their own men they thought they were their own men, and so, when the aforesaid Slavs reached the pass, they let them through. Once through, they instantly expelled the Romani and took pos- session of the aforesaid city of Salona. There they settled and thereafter began gradually to make plundering raids and destroyed the Romani who dwelt in the plains and on the higher ground and took possession of their lands.1 Thus described Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, in the mid-10th century, the migration of the Slavs from their lands to the Balkans. The story is placed chronologically “once upon a time,” at some point between the reigns of Emperors Diocletian, who brought the “Romani” to Dalmatia, and Heraclius. There is no reason to treat the story as a trustworthy historical account, but it is clear that it is meant to explain the particular situation of Salona and the former province of Dalmatia.2 No historian seems to have noticed so far that Emperor Constantine VII’s account is, after all, the only written testimony of 1 Constantine Porphyrogenitus, On the Administration of the Empire 29, pp. -

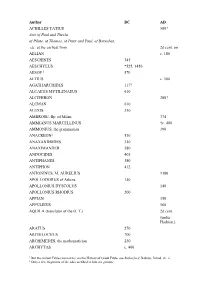

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3

Menander Protector, Fragments 6.1-3 Sasanika Sources History of Menander the Guardsman (Menander Protector) was written at the end of the sixth century CE by a minor official of the Roman/Byzantine court. The original text is in Greek, but has survived only in a fragmentary form, quoted in compilations and other historical writings. The author, Menander, was a native of Constantinople, seemingly from a lowly class and initially himself not worthy of note. In a significant introductory passage, he courageously admits to having undertaken the writing of his History (’ st a) as a way of becoming more respectable and forging himself a career. He certainly was a contemporary and probably an acquaintance of the historian Theophylact Simocatta and worked within the same court of Emperor Maurice. His title of “Protector” seems to suggest a military position, but most scholars suspect that this was only an honorary title without any real responsibilities. Menander’s history claims to continue the work of Agathias and so starts from the date that Agathias left off, namely AD 557. His style of presentation, if not his actual writing style, are thus influenced by Agathias, although he seems much less partial than the former in presentation of the events. He seems to have had access to imperial archives and reports and consequently presents us with a seemingly accurate version of the events, although at time he might be exaggerating some of his facts. The following is R. C. Blockley’s English translation of the fragments 6.1-3 of Menander Protector’s History, which deals directly with the Sasanian-Roman peace treaty of 562 and provides us with much information about the details of negotiations that took place around this treaty. -

The Geopolitics on the Silk Road

109 The Geopolitics on the Silk Road: Resurveying the Relationship of the Western Türks with Byzantium through Their Diplomatic Communications Li Qiang, Stefanos Kordosis* The geopolitics pertaining to the Silk Road network in the period from the 6th to the 7th cen- tury (the final, albeit important, period of Late Antiquity) was intertwined with highly strate- gic dimensions.1 The frequent arrival of hoards of nomadic peoples from inner Eurasia at the borders of the existing sedentary empires and their encounters and interactions formed the complicated political ecology of the period. These empires attempted to take advantage of the newly shaped situation arising after such great movements strategically, each in their own interest. How did they achieve their goals and what problems were they confronted with? In this paper, I will focus on the relations the Western Türks had with Byzantium and use it as an example in order to resurvey these complicated geopolitics. In the first part, attention will be given to the collection of Byzantine literature concerning the Western Türks. Then, on the basis of the sources, the four main exchanges of delegations between the Western Türks and Byzantium will be discussed, in which the important status of the 563 embassy – as it was the first Türk delegation sent to Byzantium – will be emphasized. The possible motives behind the dispatch of the delegations and the repercussions they had will be presented. Finally, through reviewing the diplomatic communication between the Western Türks and Byzantium, attention will be turned to the general picture of geopolitics along the Silk Road, claiming that the great empire of the West – similar to today’s superpowers – by means of their resources (mainly diplomacy) manipulated the geopolitics on the Silk Road, especially the nomadic people pursuing their own survival and interests, who were only treated as piec- es on a chessboard for keeping the balance with the rest of the superpowers. -

Studies in Theophanes

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 19 studies in theophanes edited by Marek Jankowiak & Federico Montinaro Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2015 INTRODUCTION by Marek Jankowiak & Federico Montinaro This book presents the proceedings of the conference “The Chronicle of Theophanes: sources, composition, transmission,” organized by the editors in Paris in September 2012. The Chronicle attributed to Theophanes the Confessor († 817 or 818) is an annalistic compilation continuing the world chronicle of George Synkellos and spanning more than five hundred years of Byzantine history, from Diocletian’s accession to the eve of the second Iconoclasm (ad 284–813). It stands as the major Greek source on Byzantium’s “Dark Centuries,” for which its author relied on now lost sources covering, notably, the Arab conquest, the Monothelete controversy, the emergence of Bulgaria, and the first Iconoclasm. It seemed to us in 2012 that the fifteen years of research since C. Mango and R. Scott’s ground-breaking English translation1 had witnessed steady advances in the understanding of the manuscript tradition as well as in the identification and assessment of the Chronicle’s individual sources. In this regard, one source of the Chronicle, clearly related to the Western Syriac tradition, had received a particularly large share of attention. It also seemed to us, however, that on this and other matters opinions differed, while numerous questions, concerning for example the author’s method and biases, the early manuscripts, or the Latin adaptation by Anastasius, Librarian of the Roman Church († c. -

Heraclius Emperor of Byzantium

HERACLIUS EMPEROR OF BYZANTIUM WALTER E. KAEGI PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB21RP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Walter E. Kaegi 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions ofrelevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction ofany part may take place without the written permission ofCambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Adobe Garamond 11/12.5 pt. System LATEX 2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Kaegi, Walter Emil. Heraclius: emperor ofByzantium / Walter E. Kaegi. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 81459 6 1. Heraclius, Emperor ofthe East, ca. 575–641. 2. Byzantine Empire–History–Heraclius, 610–641. 3. Emperors–Byzantine Empire–Biography. I. Title. DF574 .K34 2002 949.5 013 092 –dc21 [B] 2002023370 isbn 0 521 81459 6 hardback Contents List of maps page vi List of figures vii Acknowledgments viii List of abbreviations x Introduction 1 1 Armenia and Africa: the formative years 19 2 Internal and external challenges -

Breaking Silence in the Historiography of Procopius of Caesarea

DOI 10.1515/bz-2020-0042 BZ 2020; 113(3): 981–1024 Charles Pazdernik Breaking silenceinthe historiography of Procopius of Caesarea Abstract: Procopius employs the motif of “grievinginsilence” to describethe deliberations preceding Justinian’sinvasion of Vandal North Africa in 533 (Wars 3.10.7– 8) and his vendetta against the urban prefect of Constantinople in 523(HA 9.41). Theparticularity of Procopius’ languageinthese passages makes their collocation especiallypronounced. The distance between the Wars and the Secret History,which represents itself breakingthe silence between what the Wars can state publiclyand the unvarnished truth (HA 1.1–10), may be measured by two “wise advisers” who speak when others are silent: the quaestor Proclus, warmlyrememberedfor his probity,and the praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian, afigure universallyreviled.Discontinuities between the presentation of John in the Wars and the merits of the policies he endorses prob- lematize readers’ impressions of not onlyJohn but alsothe relationship between the Wars and the historical reality the work claims to represent. Adresse: Prof.Dr. Charles F. Pazdernik, Grand Valley StateUniversity,DepartmentofClassics, One Campus Drive, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] I Twointerrelated episodes in Procopius of Caesarea’s Wars and Secret History,re- spectively,present similar but incongruous images of deliberations within high councils of state in the later Romanempire. The more straightforward of the two concerns the fateofTheodotus “the Pumpkin,”¹ an urban prefect of Constantinople duringthe reign of Justin I, whose success in cracking down against the excesses of the Blue circus faction in 523CEthreatened the interests of Justin’snephew, the future emperor Justi- nian I. -

195 Theophylact Simocatta Revisited. a Response to Andreas Gkoutzioukostas

BYZANTION NEA HELLÁS Nº 35 - 2016: 195 / 209 THEOPHYLACT SIMOCATTA REVISITED. A RESPONSE TO ANDREAS GKOUTZIOUKOSTAS FLORIN CURTA University of Florida. U.S.A Abstract: In a reply to a previous article published in Byzantion Nea Hellás, the Greek historian Andreas Gkoutzioukostas has claimed that in a passage in Book VIII of Theophylact Simocatta’s History, the word Sklavinia was used as an adjective, not as a noun, and that the Byzantine historian frequently used adjectives derived from ethnic names. This article is a demonstration that both claims are in fact wrong, as Theophylact had very precise reasons for avoiding adjectives derived from ethnic names. Such reasons have much more to do with the narrative strategies that he employed than with the norms of the Greek language. His usage of Sklavinia is also mirrored by Hugeburc of Heidenheim’s transcription of St. Willbald’s account of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Keywords: Theophylact Simocatta, Slavs, ethnicity, barbarians, Vita S. Willibaldi, Theophanes TEOFILACTO SIMOCATES REVISADO. UNA RESPUESTA A ANDREAS GKOUTZIOUKOSTAS Resumen: En una respuesta a un artículo anterior publicado en Byzantion Nea Hellás, el historiador griego Andreas Gkoutzioukostas ha afirmado que en un pasaje del Libro VIII de la Historia de Teofilacto Simocates, la palabraSklavinia se usa como adjetivo, no como sustantivo, y que el historiador bizantino frecuentemente usa adjetivos derivados de nombres étnicos. Este artículo es una demostración de que ambas afirmaciones son de hecho erróneas, ya que Teofilacto tenía razones precisas para evitar adjetivos derivados de nombres étnicos. Tales razones tienen mucho más que ver con las estrategias narrativas que empleó que con las normas de la lengua griega.