Sneak Preview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cliff Palace Teacher Resource

Teacher Resource Set Title Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park Developed by Laura Douglas, Education ala Carte Grade Level 3 – 4 Essential Questions How can primary sources help us learn about the past and how the people lived at Cliff Palace in what is now Mesa Verde National Park? What natural resources were used by the Ancestral Puebloan people that lived at Cliff Palace? How did the natural environment effect the way in which Ancestral Puebloan built their shelters? Why did the Ancestral Puebloan people migrate from Cliff Palace? Contextual Paragraph Mesa Verde National Park is located in Montezuma County, Colorado in the southwestern corner of the state. As of its nomination to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 it had more than 800 archaeological sites recorded or in the process of inventory. Today there are nearly 5,000 documented sites including about 600 cliff dwellings. Mesa Verde, which means, “green table” was inhabited by Ancestral Puebloans, a branch of the San Juan Anasazi Indians, from about 580 CE to 1300 CE. Today it is the most extensive and well-developed example of prehistoric cliff dwellings. For in depth information about Mesa Verde National Park visit the Colorado Encyclopedia at: https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/mesa-verde-national-park. Archaeologists have identified distinct periods during Mesa Verde’s habitation based on artifacts and ruins discovered there. The Cliff Palace was constructed during the Pueblo III period. According to dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), Cliff Palace construction and refurbishment happened from 1190 CE – 1260 CE, although most was done during a 20- year span. -

Sacred Smoking

FLORIDA’SBANNER INDIAN BANNER HERITAGE BANNER TRAIL •• BANNERPALEO-INDIAN BANNER ROCK BANNER ART? • • THE BANNER IMPORTANCE BANNER OF SALT american archaeologySUMMER 2014 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 SACRED SMOKING $3.95 $3.95 SUMMER 2014 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 12 HOLY SMOKE ON BY DAVID MALAKOFF M A H Archaeologists are examining the pivitol role tobacco has played in Native American culture. HLEE AS 19 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SALT BY TAMARA STEWART , PHOTO BY BY , PHOTO M By considering ethnographic evidence, researchers EU S have arrived at a new interpretation of archaeological data from the Verde Salt Mine, which speaks of the importance of salt to Native Americans. 25 ON THE TRAIL OF FLORIDA’S INDIAN HERITAGE TION, SOUTH FLORIDA MU TION, SOUTH FLORIDA C BY SUSAN LADIKA A trip through the Tampa Bay area reveals some of Florida’s rich history. ALLANT COLLE ALLANT T 25 33 ROCK ART REVELATIONS? BY ALEXANDRA WITZE Can rock art tell us as much about the first Americans as stone tools? 38 THE HERO TWINS IN THE MIMBRES REGION BY MARC THOMPSON, PATRICIA A. GILMAN, AND KRISTINA C. WYCKOFF Researchers believe the Mimbres people of the Southwest painted images from a Mesoamerican creation story on their pottery. 44 new acquisition A PRESERVATION COLLABORATION The Conservancy joins forces with several other preservation groups to save an ancient earthwork complex. 46 new acquisition SAVING UTAH’S PAST The Conservancy obtains two preserves in southern Utah. 48 point acquisition A TIME OF CONFLICT The Parkin phase of the Mississippian period was marked by warfare. -

Architecture of the Anasazi Pueblo Culture

~RCrnTECTUH.E of the ~ :~~§ ;'}"Z j [ PUEBLO CUL'J'U~ RE Charles L. n,u .IA Every story must have a beginning. This one Much work has been done in past decades to begins many centuries ago during the last stages of learn about these people thro ugh diggings, but it was the Pleistocene age. Although the North American not until 1927, when a group of archaeologists met continent was generally glaciated during this period at Pecos, New Mexico, that a uniform method of clas man y open areas occurred. Among these open areas sifying the developm ent of the cultures of the south were the lowlands bordering the Bering Sea and the west was agreed upon. The original classification un Arctic coast, the grea t central plain in Alaska, and derwent changes and modifications as it was applied parts of the main North American continent. These by various archaeo logists with many sub-classifica unglaciated avenues made possible the migration of tions used by indivduals in their own work. To solid men across Siberia, over the Berin g Strait, and onto ify the concept and to insert some uniformity into the North American continent. Moving south along archaeological work, Roberts in 1935 sugges ted some the Rocky Mountains and dispersing eastward and revisions to the original classifica tions. His revisions westwa rd in the mountain valleys to establish popula have subsequently been acce pted by many archae tion centers over the continent, a steady influx of ologists and they provide the parameter for this study. Asiatic people expanded continuously southward in Basketmaker BC·450 AD replaced Basketmaker 11 search of new land s. -

Pre-Contact North America

Pre-contact North America Colin C. Calloway, First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, 3rd Ed. (Boston and New York: Bedford/ St. Martin’s, 2008.), 20. Mesa Verde Cliff Palace:150 rooms, 23 kivas, approximately 100 people Photo by National Park Service/Flint Boardman http://www.nps.gov/meve/photosmultimedia/cultural_sites.htm Mesa Verde Small villages existed at Mesa Verde (in current-day southeastern Colorado) by AD 700 and by 1150 people were building larger cliff houses located in the canyon walls for protection from attacks. At its peak, Mesa Verde may have included 500- 1,000 cliff houses, many of which contained 1-5 rooms each (the majority are one- roomed). Visit: http://www.nps.gov/meve/historyculture/cliff_dwelli ngs_home.htm Chaco Canyon and Pueblo Bonito -Chaco Canyon was a center of trade from c. 900-1200 of the Anasazi people Photo Credit: Brad Shattuck-National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/chcu/planyourvisit/pueblo- bonito.htm Pueblo Bonito was the largest town in Chaco Canyon (current-day New Mexico) with more than 350 ground floor rooms (650-800 rooms, total), 32 kivas, and 3 great kivas (kiva-structure used for religious purposes). It was built between AD 919 and 1085 and probably inhabited into the early 12th century. Both Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon had a mixed economy of corn agriculture. Visit following link and read first two paragraphs for more information: http://www.chacoarchive.org/cra/chaco-sites/pueblo-bonito/ Cahokia circa AD 1100- 1500 (Artists rendering) Art: Greg Harlin. Sources: Bill Iseminger and Mark Esarey, Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site; John Kelly, Washington University in St. -

Cliff Palace Mesa Verde National Park

CLIFF PALACE MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK oday only swifts and swallows and insects inhabit the airy Talcove that protects Cliff Palace. But 800 years ago the dwelling was bustling with human activity. In this stunning community deep in the heart of Mesa Verde, Ancestral Pueblo people carried on the routine of their daily lives. This was also an important location within their world. Archeological research in the late 1990s reveals that Cliff Palace is different from most other sites at Mesa Verde, both in how it was built and in how it was used. A ranger-led walk down into Cliff Palace provides a closer look at the layout and con- struction of the building, and gives tantalizing hints at what makes this site unique. The one hour guided walk requires a ticket. You will descend uneven stone steps and climb four ladders for a 100 foot vertical climb. Total distance is about ¼ mile round trip (.4 km). The crown jewel of Mesa Verde National Park and an architectural masterpiece by any standard, Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America. From the rimtop overlooks, the collection of rooms, plazas, and towers fits perfectly into the sweeping sandstone overhang that has largely protected it, unpeopled and silent, since the thirteenth century. It’s impossible to be certain why Ancestral Pueblo people decided to move into the cliff-side alcoves about AD 1200 and build elaborate and expensive struc- tures like Cliff Palace. However, the sciences of archeology, ethnography, dendrochronology and a host of other disciplines offer us insights into this era in our region’s history. -

1 Ancient America and Africa

NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 2 CHAPTER 1 Ancient America and Africa Portuguese troops storm Tangiers in Morocco in 1471 as part of the ongoing struggle between Christianity and Islam in the mid-fifteenth century Mediterranean world. (The Art Archive/Pastrana Church, Spain/Dagli Orti) American Stories Four Women’s Lives Highlight the Convergence of Three Continents In what historians call the “early modern period” of world history—roughly the fif- teenth to the seventeenth century, when peoples from different regions of the earth came into close contact with each other—four women played key roles in the con- vergence and clash of societies from Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Their lives highlight some of this chapter’s major themes, which developed in an era when the people of three continents began to encounter each other and the shape of the mod- ern world began to take form. 2 NASH.7654.cp01.p002-035.vpdf 9/1/05 2:49 PM Page 3 CHAPTER OUTLINE Born in 1451, Isabella of Castile was a banner bearer for reconquista—the cen- The Peoples of America turies-long Christian crusade to expel the Muslim rulers who had controlled Spain for Before Columbus centuries. Pious and charitable, the queen of Castile married Ferdinand, the king of Migration to the Americas Aragon, in 1469.The union of their kingdoms forged a stronger Christian Spain now Hunters, Farmers, and prepared to realize a new religious and military vision. Eleven years later, after ending Environmental Factors hostilities with Portugal, Isabella and Ferdinand began consolidating their power. -

Guide to MS 4408 Jesse Walter Fewkes Papers, 1873-1927

Guide to MS 4408 Jesse Walter Fewkes papers, 1873-1927 Margaret C. Blaker and NAA Staff 2017 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Correspondence, 1873-1927.................................................................... 4 Series 2: Field Diaries, Notebooks, and Maps, 1873-1927.................................... 11 Series 3: Lectures and Articles, mostly unpublished, circa 1907-1926, undated................................................................................................................... 21 Series 4: Manuscripts by -

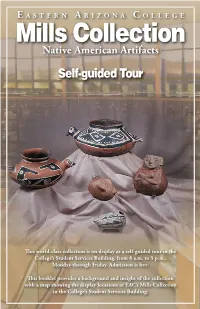

Mills Collection Native American Artifacts Self-Guided Tour

E ASTE RN A RIZONA C OLLEGE Mills Collection Native American Artifacts Self-guided Tour This world-class collection is on display as a self-guided tour in the College’s Student Services Building, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Admission is free. This booklet provides a background and insight of the collection with a map showing the display locations of EAC’s Mills Collection in the College’s Student Services Building. MillsHistory Collection of the rdent avocational archaeologists Jack Aand Vera Mills conducted extensive excavations on archaeological sites in Southeastern Arizona and Western New Mexico from the 1940s through the 1970s. They restored numerous pottery vessels and amassed more than 600 whole and restored pots, as well as over 5,000 other artifacts. Most of their work was carried out on private land in southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico. Towards the end of their archaeological careers, Jack and Vera Mills wished to have their collection kept intact and exhibited in a local facility. After extensive negotiations, the Eastern Arizona College Foundation acquired the collection, agreeing to place it on public display. Showcasing the Mills Collection was a weighty consideration when the new Student Services building at Eastern Arizona College was being planned. In fact, the building, and particularly the atrium area of the lobby, was designed with the Collection in mind. The public is invited to view the display. Admission is free and is open for self-guided tours during regular business hours, Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. -

Anasazi Ruins

AAnN archaeologicalASAZI and Cultural R DiscoveryUINS of the American Southwest September 11-19, 2020 An excellent introduction to the prehistoric Anasazi •Canyon de Chelly – called Tsegi, “rock canyon,” ruins, Hopi and Navajo people, and the natural history by the Navajo. Magnificent Canyon de Chelly of the American Southwest, this 9-day expedition actually includes two adjoining canyons, Canyon offers an opportunity to explore the archaeological del Muerto to the north and Canyon de Chelly to wonders and cultural heritage of the ancient peoples the south. In the canyon’s walls rising to heights of of the Southwest, plus striking scenic areas. over a thousand feet are houses built in open caves The Itinerary includes: by early Anasazi people. • Santa Fe – one of America’s oldest cities with adobe •• Hubbell – the Navajo people have come to Hubbell walkways, central plaza, mission, galleries, and Trading Post for years to trade for supplies. museums. • Hopi Mesas – an enclave in the enormous Navajo Reservation, the Hopi Cultural Center and Museum • Bandelier National Monument – a prehistoric Anasazi site in wooded canyon country which at Second Mesa will provide an interesting and contains many cliff and open pueblo ruins. informative picture of Indian life. • Chaco Canyon – one of the most important centers • Hovenweep National Monument – the site of of commerce and culture in the prehistoric ancient astronomers quest to understand the Southwest. Many consider Chaco to be the movement of the stars and provide meaning to architectural peak of the Anasazi culture. their people. During the Expedition, the Southwest’s • Aztec Ruins National Monument – a three-story, impressive Native American heritage, natural 500-room dwelling built over 850 years ago. -

Jesse Walter Fewkes 1850-1930

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XV -NINTH MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF JESSE WALTER FEWKES 1850-1930 BY WALTER HOUGH PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE AUTUMN MEETING, 1932 JESSE WALTER FEWKES 1850-1930 Jesse Walter Fewkes was born at Newton, Massachusetts, November 14, 1850, son of Jesse and Susan Emeline (Jewett) Fewkes. Both his parents were born at Ipswich, Massachu- setts. His mother's ancestry traced to the close of the 17th century in America. The primary educational opportunities of the period were given the boy with the long view that he should have an advanced education. The resources of the intellectual environment of Jesse Walter Fewkes at the period of 1850 were particularly rich in men and reasonably so as to material agencies. His family means, limited to the income of his father as a craftsman, were bud- geted unalterably as to the item of education, reflecting the early American belief in this essential feature. Thus the youth, Jesse, entered into the ways of learning through the primary schools and grades locally organized. There is no data giving a glimpse at his progress and capabili- ties in this formative period, only that a clergyman became in- terested in his education. Through this interest Fewkes was prepared for Harvard, and at 21 he entered the college with- out conditions. His course in the school may be marked by two periods, in which he essayed to find his particular bent that would develop into a life work. In the branch of physics we find him leaning toward the advancing field of electrical science under that de- partment at Harvard. -

Paleo-Environmental Investigations of a Cultural Landscape at Effigy Mounds National Monument

PALEO-ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATIONS OF A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AT EFFIGY MOUNDS NATIONAL MONUMENT By Sarah McGuire Bogen, MS and Sara C. Hotchkiss, PhD University of Wisconsin – Madison Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies Submitted 17 September 2007 National Park Service Great Lakes Northern Forest Cooperative Ecosystem Study Unit Cost Sharing Grant 144-ND24 Final Draft i Acknowledgements We would like to thank, Professor Evelyn Howell and especially Professor Sissel Schroeder, for guidance and valuable feedback. Colleagues who provided technical expertise and valuable ideas: Marjeta Jeraj, Ben Von Korf, Patricia Sanford, Michael Tweiten, Shelly Crausbay, and Jennifer Schmitz Rodney Rovang at EFMO supported this project with personnel in the field and sponsorship of the research. Additionally, funding from National Park Service Great Lakes Northern Forest Cooperative Ecosystem Study Unit Cost Sharing Grant, 144 ND24 made dating of the core possible. The Limnological Research Center at the University of Minnesota provided assistance with logging and initial descriptive studies of the core. Data from this study will be contributed to the North American Pollen Database and the Global Charcoal database. The cores will be archived at the National Lacustrine Core Repository, University of Minnesota. ii Abstract Effigy Mounds National Monument (EFMO) is a national monument that combines interpretation of Native American landscape features with natural resources management. EFMO was created to protect excellent examples of prehistoric Native American mounds that occur within its boundaries. Since its creation in 1949, EFMO has doubled in land area and the National Park Service (NPS) has become concerned with better interpretation and management of this cultural landscape. NPS desired more detailed information about the paleoenvironmental history of EFMO in order to inform management practices, aimed at reconfiguring the landscape to better imitate its look and feel during the Woodland cultural period. -

Mesa Verde U.S

National Park Service Mesa Verde U.S. Department of the Interior Mesa Verde National Park Mesa Verde National Park Timeline 1765 Don Juan Maria de Rivera, under orders from New Mexico governor Tomas Velez Cachupin, led what was possibly the first expedition of white men northwest from New Mexico. Rivera’s men saw ancient “ruins,” but made no identifiable reference to Mesa Verde in their journals. 1859 By 1859, several groups had entered the region, exploring both the north and south sides of Mesa Verde. The first European known to climb onto the mesa, was geologist Dr. John S. Newberry, a member of the 1859 San Juan Exploring Expedition. Although he didn’t record finding any archeological sites, the expedition was the first to officially use the name Mesa Verde. The manner in which it was identified, suggests the name was already in common usage. 1874 Pioneer photographer William Henry Jackson was photographing in the mountains northeast of Mesa Verde in August. There he met an old friend who introduced him to John Moss, a miner who had spent several years ranching and exploring near Mesa Verde. Moss offered to guide him to the ancient sites he and his men had found. With Moss leading the way into Mancos Canyon, Jackson entered Two Story House, and took the first photographs of a cliff dwelling in the Mesa Verde region. The photographs taken by Jackson that September helped call attention to the area. 1875 The second cliff dwelling in the Mesa Verde area to be named was Sixteen Window House. William H.