A History of the Ancient Southwest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. Murphy4 1 Department of Anthropology and Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB # 3115, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA, [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Archaeobotanical Consultant, 2837 E. Beverly Dr., Tucson, AZ 85716, USA 3 Consulting Archaeopalynologist, 8875 Carefree Ave., Flagstaff, AZ 86004, USA 4 Department of Plant Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Little Barley Grass (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) is a well-known native food do- mesticated in the U.S. -

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXIX Fall/Winter 2017 No. 3 and No. 4 CONTENTS Death on a Summer Night: Faulkner at Byhalia 101 By Jack D. Elliott, Jr. and Sidney W. Bondurant The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, 137 and Slavery: 1848–1860 By Elias J. Baker William Leon Higgs: Mississippi Radical 163 By Charles Dollar 2017 Mississippi Historical Society Award Winners 189 Program of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 193 Annual Meeting By Brother Rogers Minutes of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 197 Business Meeting By Elbert R. Hilliard COVER IMAGE —William Faulkner on horseback. Courtesy of the Ed Meek digital photograph collection, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. UNIV. OF MISS., THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STUDENTS, AND SLAVERY 137 The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, and Slavery: 1848-1860 by Elias J. Baker The ongoing public and scholarly discussions about many Americans’ widespread ambivalence toward the nation’s relationship to slavery and persistent racial discrimination have connected pundits and observers from an array of fields and institutions. As the authors of Brown University’s report on slavery and justice suggest, however, there is an increasing recognition that universities and colleges must provide the leadership for efforts to increase understanding of the connections between state institutions of higher learning and slavery.1 To participate in this vital process the University of Mississippi needs a foundation of research about the school’s own participation in slavery and racial injustice. The visible legacies of the school’s Confederate past are plenty, including monuments, statues, building names, and even a cemetery. -

Tribal Perspectives on the Hohokam

Bulletin of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Tucson, Arizona December 2009 Number 60 Michael Hampshire’s artist rendition of Pueblo Grande platform mound (right); post-excavation view of compound area northwest of Pueblo Grande platform mound (above) TRIBAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE HOHOKAM Donald Bahr, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, Arizona State University The archaeologists’ name for the principal pre-European culture of southern Arizona is Hohokam, a word they adopted from the O’odham (formerly Pima-Papago). I am not sure which archaeologist first used that word. It seems that the first documented but unpublished use is from 1874 or 1875 (Haury 1976:5). In any case, since around then archaeologists have used their methods to define and explain the origin, development, geographic extent, and end of the Hohokam culture. This article is not about the archaeologists’ Hohokam, but about the stories and explanations of past peoples as told by the three Native American tribes who either grew from or replaced the archaeologists’ Hohokam on former Hohokam land. These are the O’odham, of course, but also the Maricopa and Yavapai. The Maricopa during European times (since about 1550) lived on lands previously occupied by the Hohokam and Patayan archaeological cultures, and the Yavapai lived on lands of the older Hohokam, Patayan, Hakataya, Salado, and Western Anasazi cultures – to use all of the names that have been used, sometimes overlappingly, for previous cultures of the region. The Stories The O’odham word huhugkam means “something that is used up or finished.” The word consists of the verb huhug, which means “to be used up or finished,” and the suffix “-kam,” which means “something that is this way.” Huhug is generally, and perhaps only, used as an intransitive, not a transitive, verb. -

Struggle for North America Prepare to Read

0120_wh09MODte_ch03s3_s.fm Page 120 Monday, June 4, 2007 10:26WH09MOD_se_CH03_S03_s.fm AM Page 120 Monday, April 9, 2007 10:44 AM Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION 3 Instruction 3 A Piece of the Past In 1867, a Canadian farmer of English Objectives descent was cutting logs on his property As you teach this section, keep students with his fourteen-year-old son. As they focused on the following objectives to help used their oxen to pull away a large log, a them answer the Section Focus Question piece of turf came up to reveal a round, and master core content. 3 yellow object. The elaborately engraved 3 object they found, dated 1603, was an ■ Explain why the colony of New France astrolabe that had belonged to French grew slowly. explorer Samuel de Champlain. This ■ Analyze the establishment and growth astrolabe was a piece of the story of the of the English colonies. European exploration of Canada and the A statue of Samuel de Champlain French-British rivalry that followed. ■ Understand why Europeans competed holding up an astrolabe overlooks Focus Question How did European for power in North America and how the Ottawa River in Canada (right). their struggle affected Native Ameri- Champlain’s astrolabe appears struggles for power shape the North cans. above. American continent? Struggle for North America Prepare to Read Objectives In the 1600s, France, the Netherlands, England, and Sweden Build Background Knowledge L3 • Explain why the colony of New France grew joined Spain in settling North America. North America did not Given what they know about the ancient slowly. -

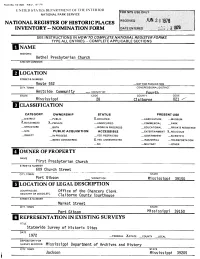

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture

9 The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture A Cosmological Expression Anna Sofaer TUDIES BY THE SOLSTICE PROJECT indicate that the solar-and-lunar regional pattern that is symmetri- Smajor buildings of the ancient Chacoan culture cally ordered about Chaco Canyon’s central com- of New Mexico contain solar and lunar cosmology plex of large ceremonial buildings (Sofaer, Sinclair, in three separate articulations: their orientations, and Williams 1987). These findings suggest a cos- internal geometry, and geographic interrelation- mological purpose motivating and directing the ships were developed in relationship to the cycles construction and the orientation, internal geome- of the sun and moon. try, and interrelationships of the primary Chacoan From approximately 900 to 1130, the Chacoan architecture. society, a prehistoric Pueblo culture, constructed This essay presents a synthesis of the results of numerous multistoried buildings and extensive several studies by the Solstice Project between 1984 roads throughout the eighty thousand square kilo- and 1997 and hypotheses about the conceptual meters of the arid San Juan Basin of northwestern and symbolic meaning of the Chacoan astronomi- New Mexico (Cordell 1984; Lekson et al. 1988; cal achievements. For certain details of Solstice Pro- Marshall et al. 1979; Vivian 1990) (Figure 9.1). ject studies, the reader is referred to several earlier Evidence suggests that expressions of the Chacoan published papers.1 culture extended over a region two to four times the size of the San Juan Basin (Fowler and Stein Background 1992; Lekson et al. 1988). Chaco Canyon, where most of the largest buildings were constructed, was The Chacoan buildings were of a huge scale and the center of the culture (Figures 9.2 and 9.3). -

Ancient Maize from Chacoan Great Houses: Where Was It Grown?

Ancient maize from Chacoan great houses: Where was it grown? Larry Benson*†, Linda Cordell‡, Kirk Vincent*, Howard Taylor*, John Stein§, G. Lang Farmer¶, and Kiyoto Futaʈ *U.S. Geological Survey, Boulder, CO 80303; ‡University Museum and ¶Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; §Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department, Chaco Protection Sites Program, P.O. Box 2469, Window Rock, AZ 86515; and ʈU.S. Geological Survey, MS 963, Denver Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225 Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved August 26, 2003 (received for review August 8, 2003) In this article, we compare chemical (87Sr͞86Sr and elemental) analyses of archaeological maize from dated contexts within Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, to potential agricul- tural sites on the periphery of the San Juan Basin. The oldest maize analyzed from Pueblo Bonito probably was grown in an area located 80 km to the west at the base of the Chuska Mountains. The youngest maize came from the San Juan or Animas river flood- plains 90 km to the north. This article demonstrates that maize, a dietary staple of southwestern Native Americans, was transported over considerable distances in pre-Columbian times, a finding fundamental to understanding the organization of pre-Columbian southwestern societies. In addition, this article provides support for the hypothesis that major construction events in Chaco Canyon were made possible because maize was brought in to support extra-local labor forces. etween the 9th and 12th centuries anno Domini (A.D.), BChaco Canyon, located near the middle of the high-desert San Juan Basin of north-central New Mexico (Fig. -

Southern Sinagua Sites Tour: Montezuma Castle, Montezuma

Information as of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center Presents: March 4, 2021 99 a.m.-5:30a.m.-5:30 p.m.p.m. SouthernSouthern SinaguaSinagua SitesSites Tour:Tour: MayMay 8,8, 20212021 MontezumaMontezuma Castle,Castle, SaturdaySaturday MontezumaMontezuma Well,Well, andand TuzigootTuzigoot $30 donation ($24 for members of Old Pueblo Archaeology Center or Friends of Pueblo Grande Museum) Donations are due 10 days after reservation request or by 5 p.m. Wednesday May 8, whichever is earlier. SEE NEXT PAGES FOR DETAILS. National Park Service photographs: Upper, Tuzigoot Pueblo near Clarkdale, Arizona Middle and lower, Montezuma Well and Montezuma Castle cliff dwelling, Camp Verde, Arizona 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday May 8: Southern Sinagua Sites Tour – Montezuma Castle, Montezuma Well, and Tuzigoot meets at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2800 Montezuma Castle Rd., Camp Verde, Arizona What is Sinagua? Named with the Spanish term sin agua (‘without water’), people of the Sinagua culture inhabited Arizona’s Middle Verde Valley and Flagstaff areas from about 6001400 CE Verde Valley cliff houses below the rim of Montezuma Well and grew corn, beans, and squash in scattered lo- cations. Their architecture included masonry-lined pithouses, surface pueblos, and cliff dwellings. Their pottery included some black-on-white ceramic vessels much like those produced elsewhere by the An- cestral Pueblo people but was mostly plain brown, and made using the paddle-and-anvil technique. Was Sinagua a separate culture from the sur- rounding Ancestral Pueblo, Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan ones? Was Sinagua a branch of one of those other cultures? Or was it a complex blending or borrowing of attributes from all of the surrounding cultures? Whatever the case might have been, today’s Hopi Indians consider the Sinagua to be ancestral to the Hopi. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT Norman, Oklahoma 2017 ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Asa Randall ______________________________ Dr. Amanda Regnier ______________________________ Dr. Scott Hammerstedt ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Bonnie Pitblado ______________________________ Dr. Michael Winston © Copyright by SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication I dedicate my dissertation to my loving grandfather, Calvin McInnish and wonderful twin sister, Kimberly Dawn Thackston. I miss and love you. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to give my sincerest gratitude to Patrick Livingood, my committee chair, who has guided me through seven years of my masters and doctoral work. I could not wish for a better committee chair. I also want to thank Amanda Regnier and Scott Hammerstedt for the tremendous amount of work they put into making me the best possible archaeologist. I would also like to thank Asa Randall. His level of theoretical insight is on another dimensional plane and his Advanced Archaeological Theory class is one of the best I ever took at the University of Oklahoma. I express appreciation to Bonnie Pitblado, not only for being on my committee but emphasizing the importance of stewardship in archaeology. -

ARIZONA INDIAN GAMING ASSOCIATION • ANNUAL REPORT FY 2006 Letter from the Chairwoman

ARIZONA INDIAN GAMING ASSOCIATION • ANNUAL REPORT FY 2006 Letter From The Chairwoman It is our pleasure to present the third Annual Report for the Arizona Indian Gaming Association (AIGA). This report celebrates the contributions that gaming tribes are making for all Arizonans. Native people have a tradition of sharing with the community, whether we are sharing our knowledge and wisdom, artistic heritage or our natural or manmade resources. This tradition of cooperation and sharing is common to all tribes and is part of our culture. In Arizona, for example, in the 1800s, when the Pima people saw the needs of the military and settlers, they willingly shared their water and food with them. Sharing is a tradition that repeats throughout our history. With the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) and the subsequent agree- ments reached with the state of Arizona for tribes to establish and continue gaming on their lands, we are now sharing the benefits from our successful enterprises with our own people and with others throughout our state. The magnitude of sharing represents a remarkable change in a very short time frame. Twenty-five years ago, no one could have imagined that Arizona tribes, always the poorest of the poor, would be contributing millions of dollars every year to support education, health care, conservation and tourism to the state of Arizona. Or 1 that hundreds of charities would be helped every year by generous grants and donations from individual tribes. While this report is a celebration of sharing, it is also a call to action. -

26064 001 Cover Page.Indd

UNIT I THE O'ODHAM O'ODHAM VILLAGE LIFE 11 Students will participate in simulated O'odham cultural activities to include an O’odham language lesson and role-playing various daily tasks such as food preparation, games, weaving and pot making. PAGE 1.7 CREATE AN O'ODHAM VILLAGE 22 Students will place a fictional O'odham village along a Santa Cruz River map while using their knowledge of cultural needs and climate restrictions. They will describe the advantages of their chosen site and draw a sketch of their village. PAGE 1.17 UNIT I - ARIZONA STATE STANDARDS - 2006 Lesson 1 - The O'odham SUBJECT STANDARD DESCRIPTION S1 C2 PO1 describe cultures of prehistoric people in the Americas S1 C2 PO2 describe cultures of Mogollon, Anasazi, Hohokam SOCIAL S1 C3 PO3 describe the location and cultural characteristics of Native STUDIES Americans S4 C5 PO1 describe human dependence on environment and resources to satisfy basic needs S1 C4 PO2 use context to determine word meaning S1 C4 PO3 determine the difference between figurative and literal language S1 C6 PO1 predict text content READING S1 C6 PO2 confirm predictions about text S2 C1 PO1 identify the conflict of a plot S2 C1 PO5 describe a character's traits S1 C1 PO1 generate ideas WRITING S1 C1 PO5 maintain record of ideas MATH S4 C1 PO2 identify a tessellation (mat weaving) SCIENCE S4 C3 PO1 describe how resources are used to meet population needs Lesson 2 - Create an O'odham Village SUBJECT STANDARD DESCRIPTION S1 C2 PO1 describe the cultures of prehistoric people in the Americas S1 C2 PO2 describe