The Journal of Mississippi History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

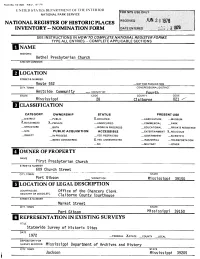

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

Buck-Horned Snakes and Possum Women: Non-White Folkore, Antebellum *Southern Literature, and Interracial Cultural Exchange

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2010 Buck-horned snakes and possum women: Non-white folkore, antebellum *Southern literature, and interracial cultural exchange John Douglas Miller College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Miller, John Douglas, "Buck-horned snakes and possum women: Non-white folkore, antebellum *Southern literature, and interracial cultural exchange" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623556. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-rw5m-5c35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. BUCK-HORNED SNAKES AND POSSUM WOMEN Non-White Folklore, Antebellum Southern Literature, and Interracial Cultural Exchange John Douglas Miller Portsmouth, Virginia Auburn University, M.A., 2002 Virginia Commonwealth University, B.A., 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January 2010 ©Copyright John D. Miller 2009 APPROVAL SHEET This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by the Committee, August 21, 2009 Professor Robert J. Scholnick, American Studies Program The College of William & Mary Professor Susan V. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Alan Gallay Lyndon B. Johnson Chair of U.S. History Tel. (817) 257-6299 Department of History and Geography Office: Reed Hall 303 Texas Christian University e-mail: [email protected] Fort Worth, TX 76129 Education Ph.D. Georgetown University, April 1986. Dissertation: “Jonathan Bryan and the Formation of a Planter Elite in South Carolina and Georgia, 1730-1780.” Awarded Distinction M.A. Georgetown University, November 1981 B.A. University of Florida, March 1978, Awarded High Honors Professional Experience Lyndon B. Johnson Chair of U.S. History, Texas Christian University, 2012- Warner R. Woodring Chair of Atlantic World and Early American History, Ohio State University, 2004- 2012 Director, The Center for Historical Research, Ohio State University, 2006-2011 Professor of History, 1995-2004; Associate Professor of History, 1991-1995, Assistant Professor of History, Western Washington University, 1988- 1991 American Heritage Association Professor for London, Fall 1996, Fall 1999 Visiting Lecturer, Department of History, University of Auckland, 1992 Visiting Professor, Departments of Afro-American Studies and History, Harvard University, 1990-1991 Visiting Assistant Professor of History and Southern Studies, University of Mississippi, 1987-1988 Visiting Assistant Professor of History, University of Notre Dame, 1986- 1987 Instructor, Georgetown University, Fall 1983; Summer 1984; Summer 1986 Instructor, Prince George’s Community College, Fall 1983 Teaching Assistant, Georgetown University, 1979-1983 1 Academic Honors Historic -

Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J. McCall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McCall, Ronald J., "Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1121. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1121 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move __________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ___________________________ by Ronald J. McCall May 2013 ________________________ Dr. Steven N. Nash, Chair Dr. Tom D. Lee Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Family History, Southern Plain Folk, Herder, Mississippi Territory ABSTRACT Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move by Ronald J. McCall This thesis explores the settlement of the Mississippi Territory through the eyes of John Hailes, a Southern yeoman farmer, from 1813 until his death in 1859. This is a family history. As such, the goal of this paper is to reconstruct John’s life to better understand who he was, why he left South Carolina, how he made a living in Mississippi, and to determine a degree of upward mobility. -

The Domestic Slave Trade

Lesson Plan: The Domestic Slave Trade Intended Audience Students in Grades 8-12 Background The importation of slaves to the United States from foreign countries was outlawed by the Act of March 2, 1807. After January 1, 1808, it was illegal to import slaves; however, the domestic slave trade thrived within the United States. With the rise of cotton in the Deep South slaves were moved and traded from state to state. Slaves were treated as commodities and listed as such on ship manifests as cargo. Slave manifests included such information as slaves’ names, ages, heights, sex and “class”. This lesson introduces students to the domestic slave trade between the states by analyzing slave manifest records of ships coming and going through the port of New Orleans, Louisiana. The Documents Slave Manifest of the Brig Algerine, March 25, 1826; Slave Manifests, 1817-1856 and 1860-1861 (E. 1630); Records of the U.S. Customs Service—New Orleans, Record Group 36; National Archives at Fort Worth. Slave Manifest of the Brig Virginia, November 18, 1823; Slave Manifests, 1817-1856 and 1860-1861 (E. 1630); Records of the U.S. Customs Service—New Orleans, Record Group 36; National Archives at Fort Worth. Standards Correlations This lesson correlates to the National History Standards. Era 4 Expansion and Reform (1801-1861) ○ Standard 2-How the industrial revolution, increasing immigration, the rapid expansion of slavery and the westward movement changed the lives of Americans and led toward regional tensions. Teaching Activities Time Required: One class period Materials Needed: Copies of the Documents Copies of the Document Analysis worksheet Analyzing the Documents Provide each student with a copy of the Written Document Analysis worksheet. -

British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Florida Frontier, 1783-1803

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 44 Number 4 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 44, Article 3 Number 4 1965 British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Florida Frontier, 1783-1803 J. Leitch Wright, Jr. Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wright, Jr., J. Leitch (1965) "British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Florida Frontier, 1783-1803," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 44 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol44/iss4/3 Wright, Jr.: British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Flo BRITISH DESIGNS ON THE OLD SOUTHWEST: FOREIGN INTRIGUE ON THE FLORIDA FRONTIER, 1783-1803 by J. LEITCH WRIGHT, JR. T IS WIDELY recognized that for years after the American Rev- olution Britain played an important role in the affairs of the Old Northwest. In spite of the peace treaty’s provisions, she con- tinued to occupy military posts ceded to the United States. Using these posts as centers, Canadian traders continued to monopolize most of the Indian commerce north of the Ohio, and the Indians in this vast region still looked to Detroit, Niagara, and Quebec, rather than to New York, Pittsburgh, or Philadelphia for com- mercial and political leadership. -

Railroad Era Resources of Southwest Arkansas, 1870-1945

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB Wo. 7 024-00/8 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior 'A'i*~~ RECEIVED 2280 National Park Service •> '..- National Register of Historic Places M&Y - 6 B96 Multiple Property Documentation Form NA1.REGISTER OF HISTORIC PUiICES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ________________ Railroad Era Resources Of Southwest Arkansas, 1870-1945 B. Associated Historic Contexts Railroad Era Resources Of Southwest Arkansas (Lafayette, Little River, Miller and Sevier Counties). 1870-1945_______________________ C. Geographical Data Legal Boundaries of Lafayette, Little River, Miller and Sevier Counties, Arkansas I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date Arkansas Historic Preservation Program State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for eva^ting related properties jor listing in the National Register. -

Panton, the Spanish Years

MERCHANT ADVENTURER IN THE OLD SOUTHWEST: WILLIAM PANTON, THE SPANISH YEARS, 1783-1801 by THOMAS DAVIS WATSON, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Annented August, 1972 13 NO'*^ PREFACE Cf The American Revolution suddenly intensified Spain's perennial problem of guarding the approaches to its vast New World empire. By war's end the United States occupied only a relatively narrow strip of land along the Atlantic coast, though its boundaries stretched westward to the Mississippi and southward to Spanish Florida. The new nation soon proved to be a restless, expansive neighbor and a threat to the tenuous Spanish hold on the North Amer ican continent. Spanish policymakers, of course, had anticipated this development long before the end of the revolution. Yet Spanish diplomacy failed to prevent the Americans from acquiring territory in the Mississippi Valley and in the Old Southwest. In the postwar years Spain endeavor? d to keep the United States from realizing its interior claims. Spanish governors of Louisiana alternately intrigued with American frontiersmen in promoting separatist movements, encouraged them to settle in Louisiana and West t'iorida, and subjected them to harassment by limiting their use of the Mississippi They attempted also to extend the northern limits of West Florida well beyond the thirty-first parallel, the boundary established in the British-American peace settlement of 11 Ill 1783. The key to success in this latter undertaking lay in the ability of Spain to deny the United States control over the southern Indians. -

The Intersection of Kinship, Diplomacy, and Trade on the Trans- Montane Backcountry, 1600-1800

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar History Faculty Research History 10-1-2008 Appalachia’s Borderland Brokers: The nI tersection of Kinship, Diplomacy, and Trade on the Trans- montane Backcountry, 1600-1800 Kevin T. Barksdale Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/history_faculty Part of the Native American Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Barksdale, Kevin T. "Appalachia’s Borderland Brokers: The nI t." Ohio Valley History Conference. Clarksville, TN. Oct. 2008. Address. This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Appalachia’s Borderland Brokers: The Intersection of Kinship, Diplomacy, and Trade on the Trans- montane Backcountry, 1600-1800 This paper and accompanying historical argument builds upon the presentation I made at last year’s Ohio Valley History Conference held at Western Kentucky University. In that presentation, I argued that preindustrial Appalachia was a complex and dynamic borderland region in which disparate Amerindian groups and Euroamericans engaged in a wide-range of cultural, political, economic, and familial interactions. I challenged the Turnerian frontier model that characterized the North American backcountry -

Indian Lands, ''Squatterism,'' and Slavery

Explorations in Economic History Explorations in Economic History 43 (2006) 486–504 www.elsevier.com/locate/eeh Indian lands, ‘‘Squatterism,’’ and slavery: Economic interests and the passage of the indian removal act of 1830 q Leonard A. Carlson *, Mark A. Roberts Department of Economics, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322-2240, United States Received 11 August 2004 Available online 23 September 2005 Abstract In May 1830, the U.S. House of Representatives narrowly passed the Indian Removal Act that authorized the president of the United States to exchange land west of the Mississippi River for Indian land in the east and appropriated $500,000 to assist tribes in the move west. Three days later the House also passed the Preemption Act of 1830, giving squatters a right of first refusal to purchase land they had occupied prior to its being opened for sale. In a recent paper, Kanazawa (1996) finds that the willingness of squatters to illegally occupy federal lands greatly raised the cost of enforcing property rights and this was a significant factor behind the passage of the first general Preemption Act in 1830. We build on his work to test the hypoth- esis that Congressmen who favored squattersÕ rights would also favor moving Indian tribes out of the old southwest. A logit analysis of the vote on the Removal Act of 1830 shows three sta- q This paper was first presented at the American Historical Association Meetings in Boston, January 2001 Thanks to Peter Coclchanis for organizing the session. I also thank participants in seminars at Emory University, the University of California, Riverside, and the International Economic History Association Congress, Buenos Aires, and the Southern Economics Association Meetings. -

A History of the Ancient Southwest

A HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT SOUTHWEST one Fore! — Orthodoxies Archaeologies: 1500 to 1850 Histories: “Time Immemorial” to 1500 BC This book is about southwestern archaeology and the ancient Southwest—two very different things. Archaeology is how we learn about the distant past. The ancient Southwest is what actu- ally happened way back then. Archaeology will never disclose or discover everything that happened in the ancient Southwest, but archaeology is our best scholarly way to know any- thing about that distant past. After a century of southwestern archaeology, we know a lot about what happened in the ancient Southwest. We know so much—we have such a wealth of data and information—that much of what we think we know about the Southwest has been necessarily compressed into conventions, classifications, and orthodoxies. This is particularly true of abstract concepts such as Anasazi, Hohokam, and Mogollon. A wall is a wall, a pot is a pot, but Anasazi is… what exactly? This book challenges several orthodoxies and reconfigures others in novel ways—“novel,” perhaps, like Gone with the Wind. I try to stick to the facts, but some facts won’t stick to me. These are mostly old facts—nut-hard verities of past generations. Orthodoxies, shiny from years of handling, slip through fingers and fall through screens like gizzard stones. We can work without them. We already know a few turkeys were involved in the story. Each chapter in this book tells two parallel stories: the development, personalities, and institutions of southwestern archaeology (“archaeologies”) and interpretations of what actu- ally happened in the ancient past (“histories”). -

Pioneers of the Old Southwest: a Chronicle of the Dark and Bloody Ground

Pioneers of the Old Southwest: A Chronicle of the Dark and Bloody Ground Constance Lindsay Skinner Pioneers of the Old Southwest by Constance Skinner *Gutenberg's Pioneers of the Old Southwest by Constance Skinner* Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the laws for your country before redistributing these files!!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Please do not remove this. This should be the first thing seen when anyone opens the book. Do not change or edit it without written permission. The words are carefully chosen to provide users with the information they need about what they can legally do with the texts. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a 501(c)(3). Presently, contributions are only being solicited from people in: Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, and Wyoming. As the requirements for other states are met, additions to this list will be made and fund raising will begin in the additional states. These donations should be made to: Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation PMB 113 1739 University Ave.