Panton, the Spanish Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY: FLORIDA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH By ROGER C. SMITH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Roger C. Smith 2 To my mother, who generated my fascination for all things historical 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Jon Sensbach and Jessica Harland-Jacobs for their patience and edification throughout the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Ida Altman, Jack Davis, and Richmond Brown for holding my feet to the path and making me a better historian. I owe a special debt to Jim Cusack, John Nemmers, and the rest of the staff at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History and Special Collections at the University of Florida for introducing me to this topic and allowing me the freedom to haunt their facilities and guide me through so many stages of my research. I would be sorely remiss if I did not thank Steve Noll for his efforts in promoting the University of Florida’s history honors program, Phi Alpha Theta; without which I may never have met Jim Cusick. Most recently I have been humbled by the outpouring of appreciation and friendship from the wonderful people of St. Augustine, Florida, particularly the National Association of Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Women’s Exchange, and my colleagues at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum and the First America Foundation, who have all become cherished advocates of this project. -

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXIX Fall/Winter 2017 No. 3 and No. 4 CONTENTS Death on a Summer Night: Faulkner at Byhalia 101 By Jack D. Elliott, Jr. and Sidney W. Bondurant The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, 137 and Slavery: 1848–1860 By Elias J. Baker William Leon Higgs: Mississippi Radical 163 By Charles Dollar 2017 Mississippi Historical Society Award Winners 189 Program of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 193 Annual Meeting By Brother Rogers Minutes of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 197 Business Meeting By Elbert R. Hilliard COVER IMAGE —William Faulkner on horseback. Courtesy of the Ed Meek digital photograph collection, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. UNIV. OF MISS., THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STUDENTS, AND SLAVERY 137 The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, and Slavery: 1848-1860 by Elias J. Baker The ongoing public and scholarly discussions about many Americans’ widespread ambivalence toward the nation’s relationship to slavery and persistent racial discrimination have connected pundits and observers from an array of fields and institutions. As the authors of Brown University’s report on slavery and justice suggest, however, there is an increasing recognition that universities and colleges must provide the leadership for efforts to increase understanding of the connections between state institutions of higher learning and slavery.1 To participate in this vital process the University of Mississippi needs a foundation of research about the school’s own participation in slavery and racial injustice. The visible legacies of the school’s Confederate past are plenty, including monuments, statues, building names, and even a cemetery. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820 Christian Pinnen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen May 2012 “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720- 1820,” examines how slaves and colonists weathered the economic and political upheavals that rocked the Lower Mississippi Valley. The study focuses on the fitful— and often futile—efforts of the French, the English, the Spanish, and the Americans to establish plantation agriculture in Natchez and its environs, a district that emerged as the heart of the “Cotton Kingdom” in the decades following the American Revolution. -

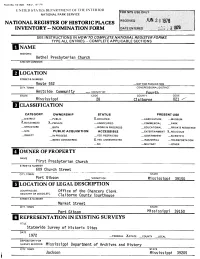

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

A Study of the Acquisition of Florida Mary Theodora Stromberg Loyola University Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1947 A Study of the Acquisition of Florida Mary Theodora Stromberg Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Stromberg, Mary Theodora, "A Study of the Acquisition of Florida" (1947). Master's Theses. Paper 381. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1947 Mary Theodora Stromberg A STUDY OF THE ACQUISITION OF FLORIDA by Sister Mary Theodora Stromberg, S.S.N.D. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master · of Arts in Loyola University February 1947 VITA Sister 1\lary Theodora Stromberg is a member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame whose principal American Motherhouse is in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She received her early education in the Milwaukee Parochial Schools, attended Notre Dame High School, and later Mount Mary Col lege of Milwaukee. There she received her Bachelor of Arts Degree in January 1937 with majors in English and History. Sister has been on the faculty of the Academy of Our Lady, Longwood, for the past nine years. Since 1943, she has been at tending the Graduate.School of Loyola Uni versity, Chicago, Illinois. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Florida, Object of Desire • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Reasons Why the United States Coveted the Floridas - Early History of the Colony - First Efforts to Acquire the Floridas - Suspension of Diplomatic Relations with Spain II. -

Rebellion in Spanish Louisiana During the Ulloa, O

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The poisonous wine from Catalonia: rebellion in Spanish Louisiana during the Ulloa, O'Reilly, and Carondelet administrations Timothy Paul Achee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Achee, Timothy Paul, "The poisonous wine from Catalonia: rebellion in Spanish Louisiana during the Ulloa, O'Reilly, and Carondelet administrations" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 399. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POISONOUS WINE FROM CATALONIA: REBELLION IN SPANISH LOUISIANA DURING THE ULLOA, O’REILLY, AND CARONDELET ADMINISTRATIONS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of History By Timothy Paul Achee, Jr. B.A., Louisiana State University, 2006 B.A. (art history), Louisiana State University, 2006 MLIS, Louisiana State University, 2008 May, 2010 For my father- I wish you were here ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis could not have been written without the support and patience of several people. I would like to take a moment to acknowledge some of them. Dr. Paul Hoffman provided invaluable guidance, encouragement and advice. -

Anglo-American Isthmian Diplomacy and the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-1965 Anglo-American Isthmian Diplomacy and the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty George W. Shipman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Shipman, George W., "Anglo-American Isthmian Diplomacy and the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty" (1965). Master's Theses. 3906. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3906 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLO-AMERICAN ISTHMIAN DIPLOMACY - AND THE CLAYTON-BULWER TREATY by George Shipman w. � A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 1965 ACI<NOWLEDGENiENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to Dr. Edward .N. MacConomy, Ghief of. the Stack and Reader Division of the Library of Congress, for his assistance in mastering that wonderful library. The author was saddened by the deaths of Dr. Charles C. Tansill and Mr. Donald Mugridge, both of whom rendered valuable bibliographical advice, particularly in the National Archives collections. Special thanks are due Dr. Willis F. Dunbar for his invaluable suggestions and advice on the style and content of this investigation. George w. Shipman ii Introduction The Panama Canal is one of the major commercial waterways of the world and, furthermore, it is vital to the defence of the United States. -

In the Nineteenth Century1

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 74 October 1981 759 Laennec's influence on some British physicians in the nineteenth century1 Alex Sakula MD FRCP Consultant Physician, Redhill General Hospital, Surrey The news of Laennec's invention in 1816 of the monoaural stethoscope for use in mediate auscultation spread rapidly from Paris throughout Europe. After the first edition of 'De L'Auscultation M&diate' appeared in 1819, interest in the method grew further and physicians from the major European medical centres, including Great Britain, travelled to Paris to learn this new technique of clinical diagnosis from the master himself. By the time that Laennec had produced the second edition of his great treatise in 1826, nearly three hundred foreign students had attended his lectures and demonstrations at L'Hopital Necker, at the College de France or at La Charite, and they included many British physicians (Sakula 1981a). In the preface to the second edition of 'De L'Auscultation Mediate' (1826), Laennec (Figure 1) listed the names of a number of his foreign students. He was obviously impressed by his British students, since he included no less than fourteen of them: Thomas Hodgkin, Alex Urquhart, Will Bennet, Townsend, Henry Riley, Rob MacKinnel, Crawfort (probably a mis-spelling of Crawford), Jones, Edwin Harrison, Patrick Scott, Cullen, James Gregory and C J B Williams. He also referred to a visit by Sir James McGrigor (1771-1858), the pioneer Director-General of Medical Services in the British army, who promised Laennec that British army surgeons and physicians would be provided with stethoscopes and would be asked to report the results of their researches with the instrument. -

Invoking Authority in the Chickasaw Nation, 1783–1795

"To Treat with All Nations": Invoking Authority in the Chickasaw Nation, 1783–1795 Jason Herbert Ohio Valley History, Volume 18, Number 1, Spring 2018, pp. 27-44 (Article) Published by The Filson Historical Society and Cincinnati Museum Center For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/689417 [ Access provided at 26 Sep 2021 02:59 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] “To Treat with All Nations” Invoking Authority in the Chickasaw Nation, 1783–1795 Jason Herbert gulayacabé was furious in the fall of 1796. Like many Chickasaws, he was stunned to learn of the recent treaty between the United States and Spain, which now jeopardized his nation’s sovereignty. The deal, Uwhich gave the Americans navigation rights to the Mississippi River and drew a new border along the 31st parallel, was the culmination of constant jockey- ing between the empires over land and trade routes in the Southeast since the American Revolution. However, the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also called Pinckney’s Treaty) was little different from other imperial pacts in that American Indians were not invited to the table. Nevertheless, the pact meant relations in Indian country were to be amended. At a meeting at San Fernando de las Barrancas (present-day Memphis), Ugulayacabé railed against his Spanish friends. “We see that our Father not only abandons us like small animals to the claws of tigers and the jaws of wolves.” The United States’ proclamations of friendship, he contin- ued, were like “the rattlesnake that caresses the squirrel in order to devour it.”1 Of course, not everyone shared Ugulayacabé’s frustrations. -

King of Battle

tI'1{1l1JOC 'Branch !J{istory Series KING OF BATTLE A BRANCH HISTORY OF THE U.S. ARMY'S FIELD ARTILLERY By Boyd L. Dastrup Office of the Command 9iistorian runited States !Jl.rmy rrraining and tIJoctrine Command ASS!STANT COMMANDANT US/\F/\S 11 MAR. 1992 ATTIN' II,., ..." (' '. 1\iIO.tIS ,")\,'/2tt Tech!lical librar fort SII), OK ~3503'031~ ..~ TRADOC Branch History Series KING OF BATTLE A BRANCH HISTORY OF THE U.S. ARMY'S FIELD ARTILLERY I t+ j f I by f f Boyd L. Dastrup Morris Swett T. n1 Property of' '1 seCh cal Library, USAFAS U.l• .1:ruy Office of the Command Historian United States Army Training and Doctrine Command Fort Monroe, Virginia 1992 u.s. ARMY TRAINING AND DOCTRINE COMMAND General Frederick M. Franks, Jr.. Commander M~or General Donald M. Lionetti Chief of Staff Dr. Henry O. Malone, Jr. Chief Historian Mr. John L. Romjue Chief, Historical Studies and Publication TRADOC BRANCH HISTORY SERIES Henry O. Malone and John L. Romjue, General Editors TRADOC Branch Histories are historical studies that treat the Army branches for which TRADOC has Armywide proponent responsibility. They are intended to promote professional development of Army leaders and serve a wider audience as a reference source for information on the various branches. The series presents documented, con- cise narratives on the evolution of doctrine, organization, materiel, and training in the individual Army branches to support the Command's mission of preparing the army for war and charting its future. iii Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dastrup, Boyd L. -

Waro Documents

DOCUMENTS 1) Treaty of Paris (February 10, 1763) The definitive Treaty of Peace and Friendship between his Britannick Majesty, the Most Christian King, and the King of Spain. Concluded at Paris the 10th day of February, 1763. To which the King of Portugal acceded on the same day. In the Name of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. So be it. Be it known to all those whom it shall, or may, in any manner, belong, It has pleased the Most High to diffuse the spirit of union and concord among the Princes, whose divisions had spread troubles in the four parts of the world, and to inspire them with the inclination to cause the comforts of peace to succeed to the misfortunes of a long and bloody war, which having arisen between England and France during the reign of the Most Serene and Most Potent Prince, George the Second, by the grace of God, King of Great Britain, of glorious memory, continued under the reign of the Most Serene and Most Potent Prince, George the Third, his successor, and, in its progress, communicated itself to Spain and Portugal: Consequently, the Most Serene and Most Potent Prince, George the Third, by the grace of God, King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick and Lunenbourg, Arch Treasurer and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire; the Most Serene and Most Potent Prince, Lewis the Fifteenth, by the grace of God, Most Christian King; and the Most Serene and Most Potent Prince, Charles the Third, by the grace of God, King of Spain and of the Indies, after having laid the foundations of peace in the preliminaries signed at Fontainebleau the third of November last; and the Most Serene and Most Potent Prince, Don Joseph the First, by the grace of God, King of Portugal and of the Algarves, after having acceded thereto, determined to compleat, without delay, this great and important work.