1 Failed Filibusters: the Kemper Rebellion, the Burr Conspiracy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Wilkinson and John Brown Letters to James Morrison

James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Brown, John, 1757-1837. Creator: Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Title: James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Dates: 1808-1818 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0577 Biographical/Historical Note James Morrison (1755-1823) was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as a navy agent and officer for the Quartermaster general. In 1791 he married Esther Montgomery; reportedly they had no children. In 1792 Morrison moved to Kentucky where he became wealthy as a manufacturer and merchant of hemp. He bequeathed money for the founding of Transylvania University in Kentucky. John Brown (1757 -1837), American lawyer and statesman heavily involved with creating the State of Kentucky. James Wilkinson (1757-1825). Following the Revolutionary War, Wilkinson moved to Kentucky, where he worked to gain its statehood. In 1787 Wilkinson became a traitor and began a long-lasting relationship as a secret agent of Spain. After Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, Wilkinson was named territorial governor of northern Louisiana. He also served as the commander in chief of the U.S. Army. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of two unrelated letters addressed to James Morrison, the first from James Wilkinson, the second is believed to be from John Brown. Index Terms Brown, John, 1757-1837. Land tenure. Letters (correspondence) Morrison, James. United States. Army. Quartermaster's Department. Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Administrative Information Custodial History Unknown. Preferred Citation [item identification], James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to John Morrison, MS 577, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia. -

Historical Background of Florida Law James Milton Carson

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Miami School of Law University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Law Review 2-1-1949 Historical Background of Florida Law James Milton Carson Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation James Milton Carson, Historical Background of Florida Law, 3 U. Miami L. Rev. 254 (1949) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol3/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF FLORIDA LAW* * JAMES MILTON CARSON ' I THE NATURE AND ORIGIN OF LAW All law must derive from the psychology of the people of each particular jurisdiction, and when we speak of the psychology of the people we mean the controlling, or "mass," or "mob" psychology of the people in any particular jurisdiction. Clarence Darrow in an.article in the American Mercury,1 went very deeply into the history of the influence of the masses of the people upon laws sought to be imposed from above, and demonstrated that even in countries whose governments are considered despotic or monarchical, the people them- selves must support the laws, or else they fall into disuse and are finally re- pealed. Since law must depend upon the psychology of the people in the particular jurisdiction, it becomes essential in trying to trace the development of law in a state such as Florida to consider the different influences which enter into the formation of the so-called "mob" psychology of the people. -

Early Understandings of the "Judicial Power" in Statutory Interpretation

ARTICLE ALL ABOUT WORDS: EARLY UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE 'JUDICIAL POWER" IN STATUTORY INTERPRETATION, 1776-1806 William N. Eskridge, Jr.* What understandingof the 'judicial Power" would the Founders and their immediate successors possess in regard to statutory interpretation? In this Article, ProfessorEskridge explores the background understandingof the judiciary's role in the interpretationof legislative texts, and answers earlier work by scholars like ProfessorJohn Manning who have suggested that the separation of powers adopted in the U.S. Constitution mandate an interpre- tive methodology similar to today's textualism. Reviewing sources such as English precedents, early state court practices, ratifying debates, and the Marshall Court's practices, Eskridge demonstrates that while early statutory interpretationbegan with the words of the text, it by no means confined its searchfor meaning to the plain text. He concludes that the early practices, especially the methodology ofJohn Marshall,provide a powerful model, not of an anticipatory textualism, but rather of a sophisticated methodology that knit together text, context, purpose, and democratic and constitutionalnorms in the service of carrying out the judiciary's constitutional role. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................... 991 I. Three Nontextualist Powers Assumed by English Judges, 1500-1800 ............................................... 998 A. The Ameliorative Power .............................. 999 B. Suppletive Power (and More on the Ameliorative Pow er) .............................................. 1003 C. Voidance Power ..................................... 1005 II. Statutory Interpretation During the Founding Period, 1776-1791 ............................................... 1009 * John A. Garver Professor ofJurisprudence, Yale Law School. I am indebted toJohn Manning for sharing his thoughts about the founding and consolidating periods; although we interpret the materials differently, I have learned a lot from his research and arguments. -

Volume II: Rights and Liberties Howard Gillman, Mark A. Graber

AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM Volume II: Rights and Liberties Howard Gillman, Mark A. Graber, and Keith E. Whittington INDEX OF MATERIALS ARCHIVE 1. Introduction 2. The Colonial Era: Before 1776 I. Introduction II. Foundations A. Sources i. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties B. Principles i. Winthrop, “Little Speech on Liberty” ii. Locke, “The Second Treatise of Civil Government” iii. The Putney Debates iv. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” v. Judicial Review 1. Bonham’s Case 2. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” C. Scope i. Introduction III. Individual Rights A. Property B. Religion i. Establishment 1. John Witherspoon, The Dominion of Providence over the Passions of Man ii. Free Exercise 1. Ward, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America 2. Penn, “The Great Case of Liberty of Conscience” C. Guns i. Guns Introduction D. Personal Freedom and Public Morality i. Personal Freedom and Public Morality Introduction ii. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” IV. Democratic Rights A. Free Speech B. Voting i. Voting Introduction C. Citizenship i. Calvin’s Case V. Equality A. Equality under Law i. Equality under Law Introduction B. Race C. Gender GGW 9/5/2019 D. Native Americans VI. Criminal Justice A. Due Process and Habeas Corpus i. Due Process Introduction B. Search and Seizure i. Wilkes v. Wood ii. Otis, “Against ‘Writs of Assistance’” C. Interrogations i. Interrogations Introduction D. Juries and Lawyers E. Punishments i. Punishments Introduction 3. The Founding Era: 1776–1791 I. Introduction II. Foundations A. Sources i. Constitutions and Amendments 1. The Ratification Debates over the National Bill of Rights a. -

Just Because John Marshall Said It, Doesn't Make It So: Ex Parte

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2000 Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789 Eric M. Freedman Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Eric M. Freedman, Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789, 51 Ala. L. Rev. 531 (2000) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MILESTONES IN HABEAS CORPUS: PART I JUST BECAUSE JOHN MARSHALL SAID IT, DOESN'T MAKE IT So: Ex PARTE BoLLMAN AND THE ILLUSORY PROHIBITION ON THE FEDERAL WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS FOR STATE PRISONERS IN THE JUDIcIARY ACT OF 1789 Eric M. Freedman* * Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law ([email protected]). BA 1975, Yale University;, MA 1977, Victoria University of Wellington (New Zea- land); J.D. 1979, Yale University. This work is copyrighted by the author, who retains all rights thereto. -

Early 19C America: Cultural Nationalism

OPENING- SAFE PLANS Study for Ch. 10 Quiz! • Jefferson (Democratic • Hamilton (Federalists) Republicans) • S-Strict Interpretation • P-Propertied and rich (State’s Rights men • A-Agriculture (Farmers) • L-Loose Interpretation • F-France over Great Britain • A-Army • E-Educated and common • N-National Bank man • S-Strong central government Jeffersonian Republic 1800-1812 The Big Ideas Of This Chapter 1. Jefferson’s effective, pragmatic policies strengthened the principles of two-party republican gov’t - even though Jeffersonian “revolution” caused sharp partisan battles 2. Despite his intentions, Jefferson became deeply entangled in the foreign-policy conflicts of the Napoleonic era, leading to a highly unpopular and failed embargo that revived the moribund Federalist Party 3. James Madison fell into an international trap, set by Napoleon, that Jefferson had avoided. The country went to war against Britain. Western War Hawks’ enthusiasm for a war with Britain was matched by New Englanders’ hostility. “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists” Is that true? Economically? Some historians say they are the same b/w Jefferson and Hamilton both dealt with rich people - be they merchants or southern planters Some historians say they are the same b/c Jefferson did not hold to his “Strict Constructionist” theory because 1. Louisiana purchase 2. Allowing the Nat’l bank Charter to expire rather than “destroying it” as soon as he took office 1800 Election Results 1800 Election Results (16 states in the Union) Thomas Democratic Virginia 73 52.9% -

Indiana Magazine of History

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY VOLUMEXXV DECEMBER, 1929 NUMBER4 The Burr Conspiracy In Indiana* By ISAACJ. Cox Indiana in the days of the Burr Conspiracy embraced a much larger area than today-at least technically. It extend- ed westward from the boundary of the recently-created state of Ohio to the Mississippi. The white settlements within this area were, it is true, few and scattering. The occasional clearings within the forests were almost wholly occupied by Indians slowly receding before the advance of a civilization that was too powerful for them. But sparse as was the popu- lation of the frontier territory when first created, its infini- tesimal average per square mile had been greatly lowered in 1804, for Congress had bestowed upon its governor the ad- ministration of that part of Louisiana that lay above the thirty-third parallel. As thus constituted, it was a region of boundless aspira- tions-a fitting stage for two distinguished travelers who journeyed through it the following year. Within its extended confines near the mouth of the Ohio lay Fort Massac, where in June, '1805, Burr held his mysterious interview with Wilkinson,' and also the cluster of French settlements from which William Morrison, the year before, had attempted to open trading relations with Santa Fe2-a project in which Wilkinson was to follow him. It was here that Willrinson, the second of this sinister pair, received from his predecessor a letter warning him against political factions in his new juris- diction.a By this act Governor Harrison emphasized not only his own personal experiences, but also the essential connection of the area with Hoosierdom. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Ambition Graphic Organizer

Ambition Graphic Organizer Directions: Make a list of three examples in stories or movies of characters who were ambitious to serve the larger good and three who pursued their own self-interested ambition. Then complete the rest of the chart. Self-Sacrificing or Self-Serving Evidence Character Movie/Book/Story Ambition? (What did they do?) 1. Self-Sacrificing 2. Self-Sacrificing 3. Self-Sacrificing 1. Self-Serving 2. Self-Serving 3. Self-Serving HEROES & VILLAINS: THE QUEST FOR CIVIC VIRTUE AMBITION Aaron Burr and Ambition any historical figures, and characters in son, the commander of the U.S. Army and a se- Mfiction, have demonstrated great ambition cret double-agent in the pay of the king of Spain. and risen to become important leaders as in politics, The two met privately in Burr’s boardinghouse and the military, and civil society. Some people such as pored over maps of the West. They planned to in- Roman statesman, Cicero, George Washington, and vade and conquer Spanish territories. Martin Luther King, Jr., were interested in using The duplicitous Burr also met secretly with British their position of authority to serve the republic, minister Anthony Merry to discuss a proposal to promote justice, and advance the common good separate the Louisiana Territory and western states with a strong moral vision. Others, such as Julius from the Union, and form an independent western Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Adolf Hitler were confederacy. Though he feared “the profligacy of often swept up in their ambitions to serve their own Mr. Burr’s character,” Merry was intrigued by the needs of seizing power and keeping it, personal proposal since the British sought the failure of the glory, and their own self-interest. -

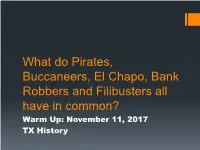

Filibusters All Have in Common? Warm Up: November 11, 2017 TX History

What do Pirates, Buccaneers, El Chapo, Bank Robbers and Filibusters all have in common? Warm Up: November 11, 2017 TX History FILIBUSTER .A person who wages an unofficial war on a country. They act on their own benefit. They don’t carry out the plan of any government. (FORTUNE SEEKERS-CRIMINALS) OTHER NAMES FOR FILIBUSTERS: •IN OTHER COUNTRIES, FILIBUSTERS ARE KNOWN BY OTHER NAMES: •BUCCANEER-----FRENCH •PIRATES----------SPANISH •FREE-BOOTERS--BRITISH Philip Nolan . Horse trader from the U.S. Claimed he was in Texas to buy and sell horses for Spain . Spain thought he was working for U.S. as a spy . Nolan explored and made maps of Texas . The Spanish ambushed him and killed him near Waco Double-Agent .A person who is hired to spy on one country but is secretly spying on the country that hired him. General James Wilkinson .U.S. General hired by Spain as a double- agent .Hired to take Louisiana and Kentucky from U.S. .Plotted with former U.S. VP Aaron Burr to take those lands for themselves General James Wilkinson . Double crosses Burr and testifies against him . Orders Zebulon Pike to explore Spanish New Mexico . Helped settle a border dispute between Texas and Louisiana . The Neutral Ground Agreement Augustus Magee . U.S. Army Lieutenant sent to Neutral Zone to catch criminals . Angry that he did not get a promised promotion . Joins up with a rebel named Bernardo Gutierrez to free Mexico from Spanish rule . Both men decide to wage war against Spanish rule Gutierrez-Magee Expedition . Gutierrez-Magee attack and capture Nacogdoches in 1812 . -

Popular Impressions of Antebellum Filibusters: Support and Opposition

POPULAR IMPRESSIONS OF ANTEBELLUM FILIBUSTERS: SUPPORT AND OPPOSITION IN THE MEDIA _____________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University Dominguez Hills ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in The Humanities _______________________ by Robert H. Zorn Summer 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TITLE PAGE ……………………………………………………………………………...i TABLE OF CONTENTS ………………………………………………………………...ii LIST OF FIGURES ……………………………………………………………………...iii ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………………..iv CHAPTER 1. THE FILIBUSTER IDEOLOGY …………………………….......................................1 2. WILLIAM WALKER AND HENRY CRABB, EXCEPTIONAL AMERICANS …...12 3. THE IMPACT OF THE PRESS ON PUBLIC PERCEPTION ………………………26 4. NON-FICTION’S ROLE IN SUPPORTING THE FILIBUSTER IDENTITY ……...39 5. DEPICTIONS OF FILIBUSTERS IN FICTION AND ART ………...….………….. 47 6. AN AMBIGUOUS LEGACY ……………………………………….……...……….. 56 WORKS CITED ………………………………………………………………………... 64 ii LIST OF FIGURES PAGE 1. National Monument in San Jose Costa Rica Depicting the Defeat of William Walker................................................................53 2. Playbill of 1857 Featuring an Original Musical Theatre Production Based on William Walker .......................................................55 iii ABSTRACT The term “filibuster” in the 1800s was nearly synonymous with, and a variation of, the word “freebooter;” pirate to some, liberator to others. Prompted by the belief in Manifest Destiny, increased tensions regarding slavery, -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary.