Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Carolina V. North Carolina - Some Problems Arising in an Easy Coast Water Dispute

Wyoming Law Review Volume 12 Number 1 Article 1 January 2012 South Carolina v. North Carolina - Some Problems Arising in an Easy Coast Water Dispute Kristin Linsley Myles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlr Recommended Citation Myles, Kristin Linsley (2012) "South Carolina v. North Carolina - Some Problems Arising in an Easy Coast Water Dispute," Wyoming Law Review: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlr/vol12/iss1/1 This Special Section is brought to you for free and open access by Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wyoming Law Review by an authorized editor of Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. Myles: South Carolina v. North Carolina - Some Problems Arising in an Ea WYOMING LAW REVIEW VOLUME 12 2012 NUMBER 1 COMMENTARY SOUTH CAROLINA V. NORTH CAROLINA— SOME PROBLEMS ARISING IN AN EAST COAST WATER DISPUTE Kristin Linsley Myles* INTRODUCTION In June 2007, South Carolina sought leave from the Supreme Court of the United States to file an original bill of complaint. South Carolina asserted that North Carolina was using more than its share of the waters of the Catawba River, which flows from the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina past Charlotte and into South Carolina at Lake Wylie. Among other things, South Carolina claimed that North Carolina had improperly approved inter-basin transfers of water from the Catawba into other river systems. South Carolina sought an equitable apportionment of the waters of the Catawba, and an injunction against further transfers. North Carolina opposed the filing of the complaint on the ground that the issue of the flow and usage of the Catawba already was the subject of a proceeding before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) on an application by Duke Energy to renew its fifty-year license for eleven power plants along the Catawba. -

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXIX Fall/Winter 2017 No. 3 and No. 4 CONTENTS Death on a Summer Night: Faulkner at Byhalia 101 By Jack D. Elliott, Jr. and Sidney W. Bondurant The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, 137 and Slavery: 1848–1860 By Elias J. Baker William Leon Higgs: Mississippi Radical 163 By Charles Dollar 2017 Mississippi Historical Society Award Winners 189 Program of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 193 Annual Meeting By Brother Rogers Minutes of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 197 Business Meeting By Elbert R. Hilliard COVER IMAGE —William Faulkner on horseback. Courtesy of the Ed Meek digital photograph collection, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. UNIV. OF MISS., THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STUDENTS, AND SLAVERY 137 The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, and Slavery: 1848-1860 by Elias J. Baker The ongoing public and scholarly discussions about many Americans’ widespread ambivalence toward the nation’s relationship to slavery and persistent racial discrimination have connected pundits and observers from an array of fields and institutions. As the authors of Brown University’s report on slavery and justice suggest, however, there is an increasing recognition that universities and colleges must provide the leadership for efforts to increase understanding of the connections between state institutions of higher learning and slavery.1 To participate in this vital process the University of Mississippi needs a foundation of research about the school’s own participation in slavery and racial injustice. The visible legacies of the school’s Confederate past are plenty, including monuments, statues, building names, and even a cemetery. -

Mississippi-State of the Union

MISSISSIPPI-STATE OF THE UNION DURING THE PAST several years in which the struggle for human rights rights in our country has reached a crescendo level, the state of ~ississippi has periodically been a focal point of national interest. The murder of young Emmett Till, the lynching of Charles Mack Parker in the "moderate" Gulf section of Mississippi, the "freedom rides" to Jackson, the events at Oxford, Mississippi, and the triple lynching of the martyred Civil Rights workers, Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, have, figuratively, imprinted Mississippi on the national conscience. In response to the national concern arising from such events, most writings about Mississippi have been in the nature of reporting, with emotional appeal and shock-value being the chief characteristics of such writing. FREEDOMWAYS is publishing this special issue on Mississippi to fill a need both for the Freedom Movement and the country. The need is for an in-depth analysis of Mississippi; of the political, economic and cultural factors which have historically served to institutionalize racism in this state. The purpose of such an analysis is perhaps best expressed in the theme that we have chosen: "Opening Up the Closed Society"; the purpose being to provide new insights rather than merely repeating well-known facts about Mississippi. The shock and embarrassment which events in Mississippi have sometimes caused the nation has also led to the popular notion that Mississippi is some kind of oddity, a freak in the American scheme-of-things. How many Civil Rights demonstrations have seen signs proclaiming-"bring Mississippi back into the Union." This is a well-intentioned but misleading slogan. -

The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820 Christian Pinnen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen May 2012 “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720- 1820,” examines how slaves and colonists weathered the economic and political upheavals that rocked the Lower Mississippi Valley. The study focuses on the fitful— and often futile—efforts of the French, the English, the Spanish, and the Americans to establish plantation agriculture in Natchez and its environs, a district that emerged as the heart of the “Cotton Kingdom” in the decades following the American Revolution. -

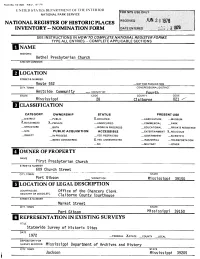

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

County Government in Mississippi Fifth Edition

County Government in Mississippi FIFTH EDITION County Government in Mississippi Fifth Edition Sumner Davis and Janet P. Baird, Editors Contributors Michael T. Allen Roberto Gallardo Kenneth M. Murphree Janet Baird Heath Hillman James L. Roberts, Jr. Tim Barnard Tom Hood Jonathan M. Shook David Brinton Samuel W. Keyes, Jr. W. Edward Smith Michael Caples Michael Keys Derrick Surrette Brad Davis Michael Lanford H. Carey Webb Sumner Davis Frank McCain Randall B. Wall Gary E. Friedman Jerry L. Mills Joe B. Young Judy Mooney With forewords by Gary Jackson, PhD, and Derrick Surrette © 2015 Center for Government & Community Development Mississippi State University Extension Service Mississippi State, Mississippi 39762 © 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the Center for Government & Community Development, Mississippi State University Extension Service. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the organization and operation of county government in Mississippi. It is distributed with the understanding that the editors, the individual authors, and the Center for Government & Community Development in the Mississippi State University Extension Service are not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required by the readers, the services of the Office of the Attorney General of Mississippi, the Office of the State Auditor of Mississippi, a county attorney, or some other competent professional should be sought. FOREWORD FROM THE MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION SERVICE The Mississippi State University Extension Service is a vital, unbiased, research-based, client- driven organization. -

Monck's Corner, Berkeley County, South Carolina

Monck's Corner, Berkeley County, South Carolina by Maxwell Clayton Orvin, 1951 In Memoriam John Wesley Orvin, first Mayor of Moncks Corner, S.C., b. March 13, 1854, d. December 17, 1916.He was the son of John Riley Orvin, a Confederate States Soldier in Co. E., Fifth S.C. Cavalry and Salena Louise Huffman, South Carolina. Transcribed by D. Whitesell for South Carolina Genealogy Trails PREFACE The text of this little book is based on matter compiled for a general history of Berkeley County, and is presented in advance of that unfinished undertaking at the request of several persons interested in the early history of the county seat and its predecessor. Recorded in this volume are facts gleaned from newspaper articles, official documents, and hitherto unpublished data vouched for by persons of undoubted veracity. Newspapers might well be termed the backbone of history, but unfortunately few issues of newspapers published in Berkeley County between 1882 and 1936 can now be found, and there was a dearth of persons interested in ''sending pieces" to the daily papers outside the county. Thus much valuable information about the county at large and the county seat has been lost. A complete file of The Berkeley Democrat since 1936 has been preserved by Editor Herbert Hucks, for which he will undoubtedly receive the blessings of the historically minded. Pursuing the self-imposed task of compiling material for a history of the county, and for this volume, I contacted many people, both by letter and in person, and I sincerely appreciate the encouragement and help given me by practically every one consulted. -

Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan for Southwest Mississippi

- 1 - Table of Contents ITEM Page List of Maps 4 List of Tables 5 List of Figures 9 Introduction 10 1: Southwest District Characteristics 12 1.1: Geography 12 1.2: Demographics 17 1.3: Climate 23 1.4: Economy 23 2: Documentation of the Planning Process 25 2.1: Background 25 2.2: Plan Jurisdictions 25 2.3: Methodology 26 2.4: Roles of the Participants 26 PDD Staff 26 Jurisdictional Representatives 27 2.5: Involvement of the Public and/or Other Interested Parties 27 3: Risk Assessment 30 3.1: Organization of this Section 30 3.2: Critical Facilities 30 3.3: Hazard Identification 30 3.4: Earthquake 32 3.5: Hurricane 35 3.6: Flooding 39 Types of Flooding 39 3.7: Tornado 56 Tornado Severity 56 3.8: Dam Failure 61 3.9: Wildfire 64 3.10: Radiological Disaster 67 3.11: Winter Storm 68 3.12: Assessing Vulnerability-Overall Summary and Impact 69 4: Comprehensive Regional Hazard Mitigation Program 99 - 2 - Introduction 99 4.1: Goals and Objectives 99 Goals 99 Objectives 100 4.2: Local Capability Assessment 100 General Authorities and Programs 100 Planning and Zoning 101 Fire Codes 101 Building and Other Codes 101 Local Emergency Management 102 Water Management and Flood Control Districts 102 Flood Insurance 103 Tables of Community Mitigation Capability Assessment 103 4.3: Hazard Mitigation Strategies 106 Earthquake 107 Hurricane 120 Flooding 188 Tornado 225 Dam Failure 251 Wildfire 275 Radiological Hazard 302 Winter Storm 333 5: Plan Maintenance Process 348 5.1: Monitoring, Evaluating and Updating the Plan 348 Monitoring 348 Evaluating 348 Updating -

Cultural Resources Overview

United States Department of Agriculture Cultural Resources Overview F.orest Service National Forests in Mississippi Jackson, mMississippi CULTURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW FOR THE NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI Compiled by Mark F. DeLeon Forest Archaeologist LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI USDA Forest Service 100 West Capitol Street, Suite 1141 Jackson, Mississippi 39269 September 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures and Tables ............................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 1 Cultural Resources Cultural Resource Values Cultural Resource Management Federal Leadership for the Preservation of Cultural Resources The Development of Historic Preservation in the United States Laws and Regulations Affecting Archaeological Resources GEOGRAPHIC SETTING ................................................ 11 Forest Description and Environment PREHISTORIC OUTLINE ............................................... 17 Paleo Indian Stage Archaic Stage Poverty Point Period Woodland Stage Mississippian Stage HISTORICAL OUTLINE ................................................ 28 FOREST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ............................. 35 Timber Practices Land Exchange Program Forest Engineering Program Special Uses Recreation KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE FOREST........... 41 Bienville National Forest Delta National Forest DeSoto National Forest ii KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

Spring/Summer 2016 No

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXVIII Spring/Summer 2016 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction to Vintage Issue 1 By Dennis J. Mitchell Mississippi 1817: A Sociological and Economic 5 Analysis (1967) By W. B. Hamilton Protestantism in the Mississippi Territory (1967) 31 By Margaret DesChamps Moore The Narrative of John Hutchins (1958) 43 By John Q. Anderson Tockshish (1951) 69 By Dawson A. Phelps COVER IMAGE - Francis Shallus Map, “The State Of Mississippi and Alabama Territory,” courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The original source is the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection. Recent Manuscript Accessions at Mississippi Colleges 79 University Libraries, 2014-15 Compiled by Jennifer Ford The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. Periodicals paid at Jackson, Mississippi. Postmaster: Send address changes to the Mississippi Historical Society, P.O. Box 571, Jackson, MS 39205-0571. Email [email protected]. © 2018 Mississippi Historical Society, Jackson, Miss. The Department of Archives and History and the Mississippi Historical Society disclaim any responsibility for statements made by contributors. INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction By Dennis J. Mitchell Nearing my completion of A New History of Mississippi, I was asked to serve as editor of The Journal of Mississippi History (JMH).