Exhibition Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820 Christian Pinnen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen May 2012 “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720- 1820,” examines how slaves and colonists weathered the economic and political upheavals that rocked the Lower Mississippi Valley. The study focuses on the fitful— and often futile—efforts of the French, the English, the Spanish, and the Americans to establish plantation agriculture in Natchez and its environs, a district that emerged as the heart of the “Cotton Kingdom” in the decades following the American Revolution. -

County Government in Mississippi Fifth Edition

County Government in Mississippi FIFTH EDITION County Government in Mississippi Fifth Edition Sumner Davis and Janet P. Baird, Editors Contributors Michael T. Allen Roberto Gallardo Kenneth M. Murphree Janet Baird Heath Hillman James L. Roberts, Jr. Tim Barnard Tom Hood Jonathan M. Shook David Brinton Samuel W. Keyes, Jr. W. Edward Smith Michael Caples Michael Keys Derrick Surrette Brad Davis Michael Lanford H. Carey Webb Sumner Davis Frank McCain Randall B. Wall Gary E. Friedman Jerry L. Mills Joe B. Young Judy Mooney With forewords by Gary Jackson, PhD, and Derrick Surrette © 2015 Center for Government & Community Development Mississippi State University Extension Service Mississippi State, Mississippi 39762 © 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the Center for Government & Community Development, Mississippi State University Extension Service. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the organization and operation of county government in Mississippi. It is distributed with the understanding that the editors, the individual authors, and the Center for Government & Community Development in the Mississippi State University Extension Service are not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required by the readers, the services of the Office of the Attorney General of Mississippi, the Office of the State Auditor of Mississippi, a county attorney, or some other competent professional should be sought. FOREWORD FROM THE MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION SERVICE The Mississippi State University Extension Service is a vital, unbiased, research-based, client- driven organization. -

Spring/Summer 2016 No

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXVIII Spring/Summer 2016 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction to Vintage Issue 1 By Dennis J. Mitchell Mississippi 1817: A Sociological and Economic 5 Analysis (1967) By W. B. Hamilton Protestantism in the Mississippi Territory (1967) 31 By Margaret DesChamps Moore The Narrative of John Hutchins (1958) 43 By John Q. Anderson Tockshish (1951) 69 By Dawson A. Phelps COVER IMAGE - Francis Shallus Map, “The State Of Mississippi and Alabama Territory,” courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The original source is the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection. Recent Manuscript Accessions at Mississippi Colleges 79 University Libraries, 2014-15 Compiled by Jennifer Ford The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. Periodicals paid at Jackson, Mississippi. Postmaster: Send address changes to the Mississippi Historical Society, P.O. Box 571, Jackson, MS 39205-0571. Email [email protected]. © 2018 Mississippi Historical Society, Jackson, Miss. The Department of Archives and History and the Mississippi Historical Society disclaim any responsibility for statements made by contributors. INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction By Dennis J. Mitchell Nearing my completion of A New History of Mississippi, I was asked to serve as editor of The Journal of Mississippi History (JMH). -

3. Status of Delegates and Resident Commis

Ch. 7 § 2 DESCHLER’S PRECEDENTS § 2.24 The Senate may, by reiterated that request for the du- unanimous consent, ex- ration of the 85th Congress. change the committee senior- It was so ordered by the Senate. ity of two Senators pursuant to a request by one of them. On Feb. 23, 1955,(6) Senator § 3. Status of Delegates Styles Bridges, of New Hamp- and Resident Commis- shire, asked and obtained unani- sioner mous consent that his position as ranking minority member of the Delegates and Resident Com- Senate Armed Services Committee missioners are those statutory of- be exchanged for that of Senator Everett Saltonstall, of Massachu- ficers who represent in the House setts, the next ranking minority the constituencies of territories member of that committee, for the and properties owned by the duration of the 84th Congress, United States but not admitted to with the understanding that that statehood.(9) Although the persons arrangement was temporary in holding those offices have many of nature, and that at the expiration of the 84th Congress he would re- 9. For general discussion of the status sume his seniority rights.(7) of Delegates, see 1 Hinds’ Precedents In the succeeding Congress, on §§ 400, 421, 473; 6 Cannon’s Prece- Jan. 22, 1957,(8) Senator Bridges dents §§ 240, 243. In early Congresses, Delegates when Senator Edwin F. Ladd (N.D.) were construed only as business was not designated to the chairman- agents of chattels belonging to the ship of the Committee on Public United States, without policymaking Lands and Surveys, to which he had power (1 Hinds’ Precedents § 473), seniority under the traditional prac- and the statutes providing for Dele- tice. -

Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1939 Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Seale, Lea Leslie, "Indian Place-Names in Mississippi." (1939). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7812. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the master^ and doctorfs degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection* Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author* Bibliographical references may be noted3 but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work# A library which borrows this thesis for vise by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions, LOUISIANA. STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 119-a INDIAN PLACE-NAMES IN MISSISSIPPI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisian© State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Lea L # Seale M* A*, Louisiana State University* 1933 1 9 3 9 UMi Number: DP69190 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Historical Narrative

Historical Narrative: “Historically, there were two, possibly three, Natchez Traces, each one having a different origin and purpose...” – Dawson Phelps, author of the Natchez Trace: Indian Trail to Parkway. Trail: A trail is a marked or beaten path, as through woods or wildness; an overland route. The Natchez Trace has had many names throughout its history: Chickasaw Trace, Choctaw-Chickasaw Trail, Path to the Choctaw Nation, Natchez Road, Nashville Road, and the most well known, the Natchez Trace. No matter what its name, it was developed out of the deep forests of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee, from animal paths and well-worn American Indian footpaths. With American ownership of the Mississippi Territory, an overland route linking the area to the growing country was desperately needed for communication, trade, prosperity and defense from the Spanish and English, who were neighbors on the southwestern frontier. While river travel was desirable, a direct land route to civilization was needed from Natchez in order to bring in military troops to guard the frontier, to take things downriver that were too precious to place on a boat, to return soldiers or boatmen back to the interior of the U.S., and for mail delivery and communication. The improvement of the Natchez Trace began over the issue of mail delivery. In 1798, Governor Winthrop Sargent of the Mississippi Territory asked that “blockhouses” be created along American Indian trails to serve was stops for mail carriers and travelers since it took so long to deliver the mail or travel to Natchez. In fact, a letter from Washington D.C. -

Chapter 5 Statehood and Settlement Lesson 1 Becoming a State Mississippi Territory in 1798, the U.S

Chapter 5 Statehood and Settlement Lesson 1 Becoming a State Mississippi Territory In 1798, the U.S. Congress created the Mississippi Territory. It included the land in Mississippi and Alabama today. Many new settlers came after wars in the 1800’s. They took land from the Native Americans. Squatter A squatter is a person who settles on land without any right to do so. People hoped this would allow them to own the land when it went up for sale. Land Speculators A land speculator is a person who buys land very cheaply and then sells it for a higher price. Land speculators outside of their office Steps to Statehood The land that is Alabama was part of the Mississippi Territory. Mississippi became their own state and the land that is Alabama today became the Alabama territory. William Wyatt Bibb became governor of the Alabama Territory. A legislature was formed in the AL territory. They met in 1818 and discussed the steps Alabama could take to become a state since there were already 60,000 people living in the territory. Steps to Statehood After having 60,000 people, the legislature sent a petition, or request to Congress. Congress approved our petition and passed an enabling act that enabled Alabama to become a state. This enabling act required the Alabama Territory to hold a constitutional convention. Delegates met at the convention and wrote a constitution. We also had to survey and map out Alabama’s land. President Monroe signed the papers and we became a state on December 14, 1819. Steps to Statehood The Alabama Territory governor William Wyatt Bibb becomes the first governor of Alabama. -

Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J. McCall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McCall, Ronald J., "Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1121. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1121 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move __________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ___________________________ by Ronald J. McCall May 2013 ________________________ Dr. Steven N. Nash, Chair Dr. Tom D. Lee Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Family History, Southern Plain Folk, Herder, Mississippi Territory ABSTRACT Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move by Ronald J. McCall This thesis explores the settlement of the Mississippi Territory through the eyes of John Hailes, a Southern yeoman farmer, from 1813 until his death in 1859. This is a family history. As such, the goal of this paper is to reconstruct John’s life to better understand who he was, why he left South Carolina, how he made a living in Mississippi, and to determine a degree of upward mobility. -

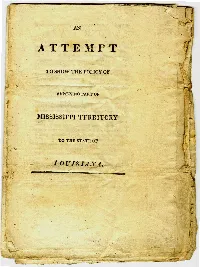

An Attempt to Show the Policy of Annexing Part of Mississippi

AN ATTEMPT TO SHOW THE POLICY OF ANNEXING PART OF MISSISSIPPI TERRITORY TO THE STATE OP I 0 l] IS I A .'-.~' ..! . {f;.":"'""".,..,.""""""""-""""""""""""".,..,., . ~ ..AN A1,TE~1P'I;, &c. , • • • ~ , # • A pe;i~ has arrived, with the return of a rr~ perous a'gricitlture and commtrce, when the: n ind . of every· Citizen must lx- more or lrss occU})i• (1 on .Yr the s\Jbject 'of extending tl:ie 'princip~s of St ·f-go Vemment in this Territory,. ·.. Within the· lim ;t ~ of the United States republican institutions havt n et with a "'success . be,·ond . the· expectation ot ll't'ir warmein1qmirers, ~nd to the utter disappointn ent of their· theoretic -opposers. ' They have becomt ~o interw·ovt>n with the sentiments habits ;md growth of the people, that· w~ have the most just expe-ctati- on thanhey will noer IX- cherished. :.. · It is; therefore-, no m~tte'r of'surprise, that the temporary · expedient· of territorial government should - ~endured wit~ some impatience, and the pu'ret principles of a permanent system sought with anxiety ·and soli('itude. But it ooght to be remem ber~d. that·the system, for which our territorial go vernment may be exchanged, will as to the limits il·may emhrace, be permanent and u"alterable. It is notconly to· affect os in· all our interests and rela tions ; b\lt posterity will· share the beneficial· effects of our ~isdom ; or regret our want of discernment. :Yb~ subject; therefore, of a change of govern ment, becomes one of vast consequence, and de serves the bt'rious and deliberate·attention of evf ry citizen. -

A GUIDE to the MAGNOLIA STATE Delbert Hosemann

A GUIDE TO THE MAGNOLIA STATE 2019 PUBLISHED BY Delbert Hosemann Secretary of State MISSISSIPPI Mississippi is the 20th state admitted to the Union. Nicknamed both “The Magnolia State” and “The Hospitality State,” Mississippi took its name from the Mississippi River which originates from the Indian word misi-ziibi, meaning “Great River” or “Father of Waters.” David Holmes was chosen as the first governor of the State. With a population of almost 3 million and a land mass of 48,434 square miles, Mississippi is the 32nd most extensive and the 31st most populous of the 50 states. The state’s density is 62.5 persons per square mile. Mississippi is heavily forested, with more than half of the state’s area covered by wild trees, including pine, cottonwood, elm, hickory, oak, pecan, sweetgum, and tupelo. The State of Mississippi is entirely composed of lowlands. Situated at 806 feet above sea level, the highest point is Woodall Mountain in the northeastern corner of the state at the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains. The lowest point is sea level at the Gulf Coast. The mean elevation in the state is 300 feet above sea level. For most of the year, the climate is mild, but becomes semi–tropical on the Gulf Coast. Summers are long, making it possible to grow crops from March through October. The average temperature in January is 48 degrees. The average temperature in July is 81 degrees, but more common daytime temperatures range in the 90s. The average rainfall is 52 inches and fall is the driest season. -

Mississippi Territory

^. •?«>!, Section VIII THE STATE PAGES •f;':-\- )r •\. >«io H>«^«». \/ • SH5 «as. / '\ State Pages / HE following section presents individual pages on all of the Tseveral states, commonwe'alths and territories. \ Included are listings of various executive officials, the Justices of the Supreme Courts, officers of the legislatures, and members of the Commissions on Interstate Cooperation. Lists of all officials are as of December, 19.61, or early 19.62. Concluding each page are popu- •\;: lation figures and other statistics, provided by the United States Bureau, of the Census. \ Preceding the individual state pages, a table presents certain his torical data on all of the states, commonwealths and territories; Ai. ./ • • l' 0 ^C THE STATES OF THE UNION-HISTORIGAL DATA* Dale Date Chroholoiical organiud admitted order of . State or other as to admission jurisdiction Capital Source of state landi Territory Union . to Union Alabama...., Montgomery Mississippi Territory. 1798(a) March 3. 1817 Dec. 14, 1819 22 Alaska....... Juneau Purchased from Russia. 1867 Aug. 24, 1912 Jan. 3.1959 49 Arlxona Plioenix Ceded by Mexico. 1848(b) Feb. 24. 1863 Feb, 14, 1912 48 Arkansas..., Little Rock Louisiana Purchase, 1803 March 2. 1819 June 15. 1836 25 California..., Sacramento Ceded by Mexico, 1848 Sept. 9. 1850 31 Colorado..... Denver Louisiana Purchase, 1803(d) Feb. 28. 1861 Aug. i: 1876 38 Connecticut. Hartford Royal charter, 1662(e) Jan. 9. 1788(0 5 Delaware.... Dov?r Swedish charter, 1638; English Dec. 7, 1787(0 1 charter 1683(e) Florida.. Tallaliassee Ceded by Spain. 1819 March 30, 1822 March 3. 1845 27 Geor^a.. Atlanta Charter. -

To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look for Assistance:” Confederate Welfare in Mississippi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 8-2017 "To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi Lisa Carol Foster University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Foster, Lisa Carol, ""To Mississippi, Alone, Can They Look For Assistance:” Confederate Welfare In Mississippi" (2017). Master's Theses. 310. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/310 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 “TO MISSISSIPPI, ALONE, CAN THEY LOOK FOR ASSISTANCE:” CONFEDERATE WELFARE IN MISSISSIPPI by Lisa Carol Foster August 2017 Approved by: _________________________________________ Dr. Susannah Ural, Committee Chair Professor, History _________________________________________ Dr. Chester Morgan, Committee