Indian Lands, ''Squatterism,'' and Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXIX Fall/Winter 2017 No. 3 and No. 4 CONTENTS Death on a Summer Night: Faulkner at Byhalia 101 By Jack D. Elliott, Jr. and Sidney W. Bondurant The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, 137 and Slavery: 1848–1860 By Elias J. Baker William Leon Higgs: Mississippi Radical 163 By Charles Dollar 2017 Mississippi Historical Society Award Winners 189 Program of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 193 Annual Meeting By Brother Rogers Minutes of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 197 Business Meeting By Elbert R. Hilliard COVER IMAGE —William Faulkner on horseback. Courtesy of the Ed Meek digital photograph collection, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. UNIV. OF MISS., THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STUDENTS, AND SLAVERY 137 The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, and Slavery: 1848-1860 by Elias J. Baker The ongoing public and scholarly discussions about many Americans’ widespread ambivalence toward the nation’s relationship to slavery and persistent racial discrimination have connected pundits and observers from an array of fields and institutions. As the authors of Brown University’s report on slavery and justice suggest, however, there is an increasing recognition that universities and colleges must provide the leadership for efforts to increase understanding of the connections between state institutions of higher learning and slavery.1 To participate in this vital process the University of Mississippi needs a foundation of research about the school’s own participation in slavery and racial injustice. The visible legacies of the school’s Confederate past are plenty, including monuments, statues, building names, and even a cemetery. -

Review of Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture by John E

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2010 Review of Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture By John E. Miller Philip Heldrich University of Washington Tacoma Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Heldrich, Philip, "Review of Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture By John E. Miller" (2010). Great Plains Quarterly. 2537. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2537 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BOOK REVIEWS 67 books and the role played by daughter Lane. He positions himself largely in opposition to William Holtz's The Ghost in the Little House (1993), which claims Lane should be consid ered the ghostwriter of the Little House books for the enormity of her contribution. Miller finds support in Caroline Fraser, William Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane: Anderson, Rosa Ann Moore, Fred Erisman, Authorship, Place, Time, and Culture. By John Ann Romines, Anita Claire Fellman, Julia E. Miller. Columbia: University of Missouri Erhhardt, and Pamela Smith Hill, each of Press, 2008. x + 263 pp. Photographs, notes, whom argues in some fashion, as does Miller, bibliography, index. $39.95. for understanding the Wilder-Lane relationship as a collaboration that differed in scope for In his third book on Laura Ingalls Wilder, each book. -

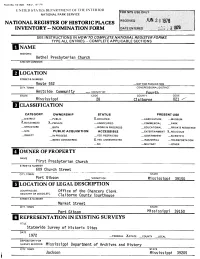

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

Kansas Settlers on the Osage Diminished Reserve: a Study Of

KANSAS SETTLERS ON THE OSAGE DIMINISHED RESERVE 168 KANSAS HISTORY A Study of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie by Penny T. Linsenmayer aura Ingalls Wilder’s widely acclaimed “Little the Sturges Treaty in the context of public land policy. Each House” series of children’s novels traces her life side committed acts of violence and property destruction with her parents and sisters from the late 1860s against the other, but historical evidence supports the until her marriage to Almanzo Wilder in 1885. proposition that the majority of both Osages and settlers LThe primary focus of Wilder’s third novel, Little House on favored and actively promoted peaceful relations. Howev- the Prairie, was the interaction between the pioneer settlers er, the overall relationship between the parties was marked of Kansas and the Osage Indians. Wilder’s family settled in by an unavoidable degree of tension. The settlers who pro- Montgomery County, Kansas, in 1869–1870, approximate- moted peaceful relations desired that the land be opened ly one year before the final removal of the Osages to Indi- up to them for settlement, and even the Osages who fa- an Territory. The novel depicts some of the pivotal events vored a speedy removal to Indian Territory merely tolerat- in the relations between the Osages and the intruding set- ed the intruders. tlers during that time period.1 The Ingalls family arrived in Kansas with a large tide The Osages ceded much of their Great Plains territory of other squatters in the summer and fall of 1869, a point at to the United States in the first half of the nineteenth cen- which relations between settlers and Osages were most tury and finally were left in 1865 with one remaining tract strained. -

Buck-Horned Snakes and Possum Women: Non-White Folkore, Antebellum *Southern Literature, and Interracial Cultural Exchange

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2010 Buck-horned snakes and possum women: Non-white folkore, antebellum *Southern literature, and interracial cultural exchange John Douglas Miller College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Miller, John Douglas, "Buck-horned snakes and possum women: Non-white folkore, antebellum *Southern literature, and interracial cultural exchange" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623556. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-rw5m-5c35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. BUCK-HORNED SNAKES AND POSSUM WOMEN Non-White Folklore, Antebellum Southern Literature, and Interracial Cultural Exchange John Douglas Miller Portsmouth, Virginia Auburn University, M.A., 2002 Virginia Commonwealth University, B.A., 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January 2010 ©Copyright John D. Miller 2009 APPROVAL SHEET This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by the Committee, August 21, 2009 Professor Robert J. Scholnick, American Studies Program The College of William & Mary Professor Susan V. -

Rose Wilder Lane, Laura Ingalls Wilder

A Reader’s Companion to A Wilder Rose By Susan Wittig Albert Copyright © 2013 by Susan Wittig Albert All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. For information, write to Persevero Press, PO Box 1616, Bertram TX 78605. www.PerseveroPress.com Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data Albert, Susan Wittig. A reader’s companion to a wilder rose / by Susan Wittig Albert. p. cm. ISBN Includes bibliographical references Wilder, Laura Ingalls, 1867-1957. 2. Lane, Rose Wilder, 1886-1968. 3. Authorship -- Collaboration. 4. Criticism. 5. Explanatory notes. 6. Discussion questions. 2 CONTENTS A Note to the Reader PART ONE Chapter One: The Little House on King Street: April 1939 Chapter Two: From Albania to Missouri: 1928 Chapter Three: Houses: 1928 Chapter Four: “This Is the End”: 1929 PART TWO Chapter Five: King Street: April 1939 Chapter Six: Mother and Daughter: 1930–1931 Chapter Seven: “When Grandma Was a Little Girl”: 1930–1931 Chapter Eight: Little House in the Big Woods: 1931 PART THREE Chapter Nine: King Street: April 1939 Chapter Ten: Let the Hurricane Roar: 1932 Chapter Eleven: A Year of Losses: 1933 PART FOUR Chapter Twelve: King Street: April 1939 Chapter Thirteen: Mother and Sons: 1933–1934 3 Chapter Fourteen: Escape and Old Home Town: 1935 Chapter Fifteen: “Credo”: 1936 Chapter Sixteen: On the Banks of Plum Creek: 1936–1937 Chapter Seventeen: King Street: April 1939 Epilogue The Rest of the Story: “Our Wild Rose at her Wildest ” Historical People Discussion Questions Bibliography 4 A Note to the Reader Writing novels about real people can be a tricky business. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Alan Gallay Lyndon B. Johnson Chair of U.S. History Tel. (817) 257-6299 Department of History and Geography Office: Reed Hall 303 Texas Christian University e-mail: [email protected] Fort Worth, TX 76129 Education Ph.D. Georgetown University, April 1986. Dissertation: “Jonathan Bryan and the Formation of a Planter Elite in South Carolina and Georgia, 1730-1780.” Awarded Distinction M.A. Georgetown University, November 1981 B.A. University of Florida, March 1978, Awarded High Honors Professional Experience Lyndon B. Johnson Chair of U.S. History, Texas Christian University, 2012- Warner R. Woodring Chair of Atlantic World and Early American History, Ohio State University, 2004- 2012 Director, The Center for Historical Research, Ohio State University, 2006-2011 Professor of History, 1995-2004; Associate Professor of History, 1991-1995, Assistant Professor of History, Western Washington University, 1988- 1991 American Heritage Association Professor for London, Fall 1996, Fall 1999 Visiting Lecturer, Department of History, University of Auckland, 1992 Visiting Professor, Departments of Afro-American Studies and History, Harvard University, 1990-1991 Visiting Assistant Professor of History and Southern Studies, University of Mississippi, 1987-1988 Visiting Assistant Professor of History, University of Notre Dame, 1986- 1987 Instructor, Georgetown University, Fall 1983; Summer 1984; Summer 1986 Instructor, Prince George’s Community College, Fall 1983 Teaching Assistant, Georgetown University, 1979-1983 1 Academic Honors Historic -

Revisiting American Indians in Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House Books

"Indians in the House": Revisiting American Indians in Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House Books Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Fatzinger, Amy S. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 22:15:14 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195771 1 “INDIANS IN THE HOUSE”: REVISITING AMERICAN INDIANS IN LAURA INGALLS WILDER'S LITTLE HOUSE BOOKS by Amy S. Fatzinger _________________________ Copyright © Amy S. Fatzinger 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Amy S. Fatzinger entitled "Indians in the House": Revisiting American Indians in Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House Books and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4/16/2008 Luci Tapahonso _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4/16/2008 Mary Jo Fox _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4/16/2008 Joseph Stauss _______________________________________________________________________ Date: _______________________________________________________________________ Date: Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J. McCall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McCall, Ronald J., "Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1121. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1121 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move __________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ___________________________ by Ronald J. McCall May 2013 ________________________ Dr. Steven N. Nash, Chair Dr. Tom D. Lee Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Family History, Southern Plain Folk, Herder, Mississippi Territory ABSTRACT Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move by Ronald J. McCall This thesis explores the settlement of the Mississippi Territory through the eyes of John Hailes, a Southern yeoman farmer, from 1813 until his death in 1859. This is a family history. As such, the goal of this paper is to reconstruct John’s life to better understand who he was, why he left South Carolina, how he made a living in Mississippi, and to determine a degree of upward mobility. -

Liberty's Belle Lived in Harlingen Norman Rozeff

Liberty's Belle Lived in Harlingen Norman Rozeff Almost to a person those of the "baby boomer" generation will fondly remember the pop- ular TV series, "Little House on the Prairie." Few, however, will have known of Rose Wilder Lane, her connection to this series, to Harlingen, and more importantly her ac- complishments. Rose Wilder Lane was born December 5, 1886 in De Smet, Dakota Territory. She was the first child of Almanzo and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Aha, this stirs a memory; isn't the latter the author of the "Little House on the Prairie" book series for children? Yes, indeed. Rose also lived the hardship life, similar to her mother's as portrayed on television. Be- fore the age of two she was sent away to her mother's parents for several months after her parents contracted diphtheria, then a deadly disease. In August 1889 she became a sister but only for the short period that her baby brother survived without ever being given a name. Rose was to have no other siblings. When a fire destroyed their home soon after the baby's death and repeated crop failures compounded the Wilder family miseries, the Wilders moved from the Dakotas to his parent's home in Spring Valley, Minnesota. In their search for a settled life and livelihood, the Wilders in 1891 went south to Westville, Florida to live with Laura's cousin Peter. Still unhappy in these surroundings, the family returned to De Smet in 1892 and lived in a rented house. Here Grandma Ingalls took care of Rose while Laura and Almanzo worked. -

The Domestic Slave Trade

Lesson Plan: The Domestic Slave Trade Intended Audience Students in Grades 8-12 Background The importation of slaves to the United States from foreign countries was outlawed by the Act of March 2, 1807. After January 1, 1808, it was illegal to import slaves; however, the domestic slave trade thrived within the United States. With the rise of cotton in the Deep South slaves were moved and traded from state to state. Slaves were treated as commodities and listed as such on ship manifests as cargo. Slave manifests included such information as slaves’ names, ages, heights, sex and “class”. This lesson introduces students to the domestic slave trade between the states by analyzing slave manifest records of ships coming and going through the port of New Orleans, Louisiana. The Documents Slave Manifest of the Brig Algerine, March 25, 1826; Slave Manifests, 1817-1856 and 1860-1861 (E. 1630); Records of the U.S. Customs Service—New Orleans, Record Group 36; National Archives at Fort Worth. Slave Manifest of the Brig Virginia, November 18, 1823; Slave Manifests, 1817-1856 and 1860-1861 (E. 1630); Records of the U.S. Customs Service—New Orleans, Record Group 36; National Archives at Fort Worth. Standards Correlations This lesson correlates to the National History Standards. Era 4 Expansion and Reform (1801-1861) ○ Standard 2-How the industrial revolution, increasing immigration, the rapid expansion of slavery and the westward movement changed the lives of Americans and led toward regional tensions. Teaching Activities Time Required: One class period Materials Needed: Copies of the Documents Copies of the Document Analysis worksheet Analyzing the Documents Provide each student with a copy of the Written Document Analysis worksheet. -

British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Florida Frontier, 1783-1803

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 44 Number 4 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 44, Article 3 Number 4 1965 British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Florida Frontier, 1783-1803 J. Leitch Wright, Jr. Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wright, Jr., J. Leitch (1965) "British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Florida Frontier, 1783-1803," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 44 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol44/iss4/3 Wright, Jr.: British Designs on the Old Southwest: Foreign Intrigue on the Flo BRITISH DESIGNS ON THE OLD SOUTHWEST: FOREIGN INTRIGUE ON THE FLORIDA FRONTIER, 1783-1803 by J. LEITCH WRIGHT, JR. T IS WIDELY recognized that for years after the American Rev- olution Britain played an important role in the affairs of the Old Northwest. In spite of the peace treaty’s provisions, she con- tinued to occupy military posts ceded to the United States. Using these posts as centers, Canadian traders continued to monopolize most of the Indian commerce north of the Ohio, and the Indians in this vast region still looked to Detroit, Niagara, and Quebec, rather than to New York, Pittsburgh, or Philadelphia for com- mercial and political leadership.