Indiana Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEAC Bulletin 58.Pdf

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE BULLETIN 58 SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE BULLETIN 58 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 DOUBLETREE BY HILTON DOWNTOWN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE Organized by: Kevin E. Smith, Aaron Deter-Wolf, Phillip Hodge, Shannon Hodge, Sarah Levithol, Michael C. Moore, and Tanya M. Peres Hosted by: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Middle Tennessee State University Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Office of Social and Cultural Resources, Tennessee Department of Transportation iii Cover: Sellars Mississippian Ancestral Pair. Left: McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture; Right: John C. Waggoner, Jr. Photographs by David H. Dye Printing of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 58 – 2015 Funded by Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Authorization No. 327420, 750 copies. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $4.08 per copy. October 2015. Pursuant to the State of Tennessee’s Policy of non-discrimination, the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or military service in its policies, or in the admission or access to, or treatment or employment in its programs, services or activities. Equal Employment Opportunity/Affirmative Action inquiries or complaints should be directed to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, EEO/AA Coordinator, Office of General Counsel, 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 2nd floor, William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower, Nashville, TN 37243, 1-888-867-7455. ADA inquiries or complaints should be directed to the ADA Coordinator, Human Resources Division, 312 Rosa L. -

Century American Gilded Picture Frames Hugh Glover

Tech Notes, Fall 2006 Care and use of 19th-century American gilded picture frames Hugh Glover icture frames are a component of most art collections and are subject to wear and tear in their functional role surrounding paint- P ings. Damage to frames occurs during exhibition, storage, and travel, and is caused by handling, hanging processes, adverse environments, neglect, and irreversible restorations. Picture frames are maintained by a variety of preservation specialist and their preservation interests have only rarely been addressed. The following is Section 4 of a larger paper, “A Description of 19th- Century American Gilded Picture Frames and an Outline of their Modern Use and Conservation,” presented in June to the Wooden Artifact Group at the 2006 annual meeting of AIC in Providence, Rhode Island. This sec- tion addresses general preservation, handling and preparation of frames for exhibition. Environment Gilded wood objects are ultra sensitive to environmental conditions and are probably more sensitive than most paintings. Gilded wood in adverse climates experiences detachment and loss of gilding/or- nament, while the accumulation of grime leads to surface darkening and cleaning campaigns that may well cause damage. The protected bright gilding that survives on shadow boxed frames of the second half-century illustrates how more exposed gilding has now been altered by grime, abrasion, and staining from moisture and grease during handling. Handling All gilded objects should be handled with non-marring gloves to avoid abrasions and staining, and even paper towels or cotton cloth will suffice. In practice, however, gilded frames are still handled with bare hands as the frame is considered a safe means of handling the artwork. -

Hard Labor, Donations Transforming White Station High's Tough Courtyard

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Wednesday, May 12, 2021 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 136 | No. 57 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Pristex’s heart for medical community starts with family ties to St. Jude CHRISTIN YATES over the city, especially in the hand sanitizer,” Latasha Harris, services that Medical District in- $32.2 million in medical supplies Courtesy of The Daily Memphian Medical District — Shelby Coun- program manager for the Mem- stitutions procure from Memphis and services with local companies The early days of the pandemic ty’s health care epicenter — were phis Medical District Collabora- area businesses. — a 26% increase from what they saw shortages of health care es- scrambling for medical-related tive’s (MMDC) Buy Local initia- Some of the Medical District’s would normally spend. “Our Buy sentials from personal protective supplies. tive, said. anchor institutions include St. Local work is usually focused on equipment (PPE) to disinfectant “It put us in a position where The Buy Local program was Jude Children’s Research Hospital non-medical spend because there wipes, surgical gowns and many we started looking for suppliers launched in 2014 to increase and Regional One Health. In 2020, other products. Institutions all making germicidal wipes and the amount of local goods and the anchor institutions spent PRISTEX CONTINUED ON P2 per 15-second increment to make the holes wide and deep enough for a newly planted tree to thrive Hard labor, donations transforming in the packed soil. -

Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-16-2019 Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site Silas Levi Chapman Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, Silas Levi, "Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1118. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY: MICROWEAR ANALYSIS OF BLADES AT THE MOUND HOUSE SITE SILAS LEVI CHAPMAN 89 Pages Understanding Middle Woodland period sites has been of considerable interest for North American archaeologists since early on in the discipline. Various Middle Woodland period (50 BCE-400CE) cultures participated in shared ideas and behaviors, such as constructing mounds and earthworks and importing exotic materials to make objects for ceremony and for interring with the dead. These shared behaviors and ideas are termed by archaeologists as “Hopewell”. The Mound House site is a floodplain mound group thought to have served as a “ritual aggregation center”, a place for the dispersed Middle Woodland communities to congregate at certain times of year to reinforce their shared identity. Mound House is located in the Lower Illinois River valley within the floodplain of the Illinois River, where there is a concentration of Middle Woodland sites and activity. -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

From the Mouths of Mississippian: Determining Biological Affinity Between the Oliver Site (22-Co-503) and the Hollywood Site (22-Tu-500)

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 From The Mouths Of Mississippian: Determining Biological Affinity Between The Oliver Site (22-Co-503) And The Hollywood Site (22-Tu-500) Hanna Stewart University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, Hanna, "From The Mouths Of Mississippian: Determining Biological Affinity Between The Oliver Site (22-Co-503) And The Hollywood Site (22-Tu-500)" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 357. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE MOUTHS OF MISSISSIPPIAN: DETERMINING BIOLOGICAL AFFINITY BETWEEN THE OLIVER SITE (22-Co-503) AND THE HOLLYWOOD SITE (22-Tu-500) A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology The University of Mississippi Hanna Stewart B.A. University of Arizona May 2014 Copyright Hanna Stewart 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The Mississippian period in the American Southeast was a period of immense interaction between polities as a result of vast trade networks, regional mating networks which included spousal exchange, chiefdom collapse, and endemic warfare. This constant interaction is reflected not only in the cultural materials but also in the genetic composition of the inhabitants of this area. Despite constant interaction, cultural restrictions prevented polities from intermixing and coalescent groups under the same polity formed subgroups grounded in their own identity as a result unique histories (Harle 2010; Milner 2006). -

1992 Program + Abstracts

The J'J'l!. Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference 1 1 ' ll\T ii~,, !,II !ffll}II II I ~\: ._~ •,.i.~.. \\\•~\,'V · ''f••r·.ot!J>,. 1'1.~•~'l'rl!nfil . ~rt~~ J1;1r:1ri WA i1. '1~;111.-U!!•ac~~ 1.!\ ill: 11111m I! nIn 11n11 !IIIIIIII Jill!! lTiili 11 HJIIJJll llIITl nmmmlllll Illlilll 1IT1Hllll .... --·---------- PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS October 16-18, 1992 Grand Rapids, Michigan F Con£eren ·, MAC 1992 Midwest Archaeological Conference 37!!! Annual Meeting October 16-18, 1992 Grand Rapids, Michigan Sponsored By: The Grand Valley State University Department of Anthropology and Sociology The Public Museum of Grand Rapids CONFERENCE ORGANIZING C0MMITIEE Janet BrashlerElizabeth ComellFred Vedders Mark TuckerPam BillerJaret Beane Brian KwapilJack Koopmans The Department of Anthropology and Sociology gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following organizations for their assistance in planning the 1992 Midwest Archaeological Conference: The Grand Valley State University Conference Planning Office The Office of the President, Grand Valley State University The Anthropology Student Organization The Public Museum of Grand Rapids Cover Rlustration: Design from Norton Zoned Dentate Pot, Mound C, Norton Mounds 8f(!r/!lA_. ARCHIVES ;z.g-'F' Office of the State Archaeologist The Universi~i of Iowa ~ TlA<-, Geuetftf 1'l!M&rmation \"l,_ "2. Registration Registration is located on the second floor of the L.V. Eberhard Center at the Conference Services office. It will be staffed from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 16; 7:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 17; and from 7:30 a.m. -

Rock Art Studies: a Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17

Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17 Keywords: Peterborough, Canada. North America. Cultural Adams, Amanda Shea resource management. Conservation and preservation. 2003 Reprinted from "Measurement in Physical Geography", Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Occasional Paper No. 3, Dept. of Geography, Trent Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, BCMaster/s Thesis :79 pgs, University, 1974. Weathering. University of British Columbia. Cited from: LMRAA, WELLM, BCSRA. Keywords: Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada. North America. Stylistic analysis. Marpole Culture. Vision. Alberta Recreation and Parks Abstract: "This study explores the stylistic variability and n.d. underlying cohesion of the petroglyphs sites located on Writing-On-Stone Provincial ParkTourist Brochure, Alberta Gabriola Island, British Columbia, a southern Gulf Island in Recreation and Parks. the Gulf of Georgia region of the Northwest Coast (North America). I view the petroglyphs as an inter-related body of Keywords: WRITING-ON-STONE PROVINCIAL PARK, ancient imagery and deliberately move away from (historical ALBERTA, CANADA. North America. "THE BATTLE and widespread) attempts at large regional syntheses of 'rock SCENE" PETROGLYPH SITE INSERT INCLUDED WITH art' and towards a study of smaller and more precise PAMPHLET. proportion. In this thesis, I propose that the majority of petroglyphs located on Gabriola Island were made in a short Cited from: RCSL. period of time, perhaps over the course of a single life (if a single, prolific specialist were responsible for most of the Allen, W.A. imagery) or, at most, over the course of a few generations 2007 (maybe a family of trained carvers). -

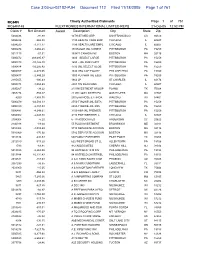

Case 3:03-Cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761

Case 3:03-cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761 MC64N Timely Authorized Claimants Page 1 of 761 MC64N148 FLEXTRONICS INTERNATIONAL LIMITED REPS 21-Oct-05 12:52 PM Claim #Net Amount Award Description City State Zip 5002436 -91.88 10TH ST MED GRP SAN FRANCISCO CA 94120 5004224 -965.80 1199 HEALTH CARE EMP CHICAGO IL 60607 5004220 -3,717.17 1199 HEALTHCARE EMPL CHICAGO IL 60607 5000476 -3,602.28 150 EAGLE JNL CORE E PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5011113 -57.51 159471 CANADA INC BOSTON MA 02116 5000472 -269,695.87 1600 - SELECT LARGE PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000473 -10,126.40 1650 - JNL FMR CAPIT PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000474 -93,205.42 1700 JNL SELECT GLOB PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5009707 -6,478.05 1838 LRG CAP EQUITY PHILADELPHIA PA 19109 5000477 -2,849.29 1900 PUTNAM JNL EQUI PITTSBURGH PA 15259 2185655 -100.43 1966 LP ST CHARLES IL 60174 5003474 -1,053.69 2001 TIN MAN FUND CHICAGO IL 60607 2095267 -38.22 210 INVESTMENT GROUP PLANO TX 75024 2057274 -755.37 22 WILLOW LIMITED PA OAK BLUFFS MA 02557 4259 -1,853.75 230 EAR NOSE & THROA WAUSAU WI 54401 5000479 -44,584.33 2750-T ROWE-JNL ESTA PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000480 -2,457.83 2850-T ROWE-JNL MID- PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000481 -4,348.61 3150-AIM-JNL PREMIER PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5004002 -2,648.80 3180 PARTNERSHIP, L. CHICAGO IL 60607 2104008 -5.20 5 - W ASSOCIATES ANDERSON SC 29622 2146318 -83.04 55 PLUS INVESTMENT BRUNSWICK ME 04011 5010968 -4,083.69 5710 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 5010969 -170.92 5782 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 1013184 -230.59 5D FAMILY PARTNERS PILET POINT TX 76258 -

Report Phase Ib Cultural Resources Survey And

REPORT PHASE IB CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY AND HISTORIC RAIL FEATURE DOCUMENTATION BLOOMFIELD GREENWAY MULTI-USE TRAIL BLOOMFIELD, CONNECTICUT Prepared for BL Companies 355 Research Parkway Meriden, CT 06450 By Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. 569 Middle Turnpike P.O. Box 543 Storrs, CT 06268 Authors: Brian Jones, Ph.D. Bruce Clouette, Ph.D. Ross K. Harper, Ph.D. February 6, 2014 Revised March 20, 2015 ABSTRACT The Town of Bloomfield, Connecticut, is planning construction of Section 1 of the Bloomfield Greenway Multi-Use Trail. The trail runs from Station 100+00 (Tunxis Avenue, Route 189/187) at the north to Station 186+00 (Tunxis Avenue, Route 189/187) at the south (Figure 1). Most of the Base Phase, which measures 8,285 feet (2,524 meters) in length, will follow the former Connecticut Western/Central New England Rail Line. The trail is planned to be approximately 11 feet wide. A 50-foot-long prefabricated bridge will span Griffin Brook, at the location of a former railroad bridge which is no longer extant. The Connecticut Department of Transportation (ConnDOT), Office of Environmental Planning (OEP), reviewed the proposed project and noted that the project area, or Area of Potential Effect (APE), possesses pre-colonial Native American archaeological sensitivity, and contains rail-related historic resources that are potentially eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. ConnDOT recommended that a Phase IB subsurface reconnaissance survey be conducted along portions of the proposed trail under current design that are archaeologically sensitive. ConnDOT further recommended that the eligibility of historic-rail-related features for listing in the National Register of Historic Places be assessed. -

Hopewell Archeology: the Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997

Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997 1. Current Research at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park By Bret J. Ruby, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio Archeological research is an essential activity at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. An active program of field research provides the information necessary to protect and preserve Hopewellian archeological resources. The program also addresses a series of long-standing questions regarding the cultural history and adaptive strategies of Hopewellian populations in the central Scioto region. Presented below are preliminary notices of recent field projects conducted by park personnel with the assistance of the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska. These recent efforts are focused on three Hopewellian centers in Ross County. Two of these centers, the Mound City Group and the Hopeton Earthworks, are administered by the National Park Service as units of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. The third center, the Spruce Hill Works, is privately owned and is being considered for possible inclusion in the park. Research at the Mound City Group Work at the Mound City Group was prompted by plans to install a set of eight new interpretive signs along a trail encircling the mounds and earthworks at the site. Although the Mound City Group has been the focus of archeological investigations for almost 150 years, previous research has focused almost exclusively on the mounds and earthworks themselves (Figure 1), with little attention paid to identifying archeological resources that may lie just outside the earthwork walls. Figure 1. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Submerged Evidence of Early Human Occupation in the New York Bight A Dissertation Presented by Daria Elizabeth Merwin to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology (Archaeology) Stony Brook University August 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Daria Elizabeth Merwin We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. David J. Bernstein, Ph.D., Advisor Associate Professor, Anthropological Sciences John J. Shea, Ph.D., Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, Anthropological Sciences Elizabeth C. Stone, Ph.D. Professor, Anthropological Sciences Nina M. Versaggi, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology, Binghamton University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Submerged Evidence of Early Human Occupation in the New York Bight by Daria Elizabeth Merwin Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology (Archaeology) Stony Brook University 2010 Large expanses of the continental shelf in eastern North America were dry during the last glacial maximum, about 20,000 years ago. Subsequently, Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene climatic warming melted glaciers and caused global sea level rise, flooding portions of the shelf and countless archaeological sites. Importantly, archaeological reconstructions of human subsistence and settlement patterns prior to the establishment of the modern coastline are incomplete without a consideration of the whole landscape once available to prehistoric peoples and now partially under water.