Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

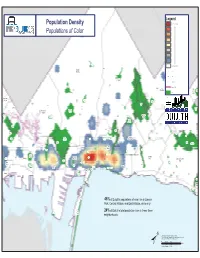

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

A Bioarchaeological Study of a Prehistoric Michigan Population: Fraaer-Tyra Site (20Sa9) Allison June Muhammad Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 A Bioarchaeological Study Of A Prehistoric Michigan Population: Fraaer-Tyra Site (20sa9) Allison June Muhammad Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Organic Chemistry Commons, and the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Muhammad, Allison June, "A Bioarchaeological Study Of A Prehistoric Michigan Population: Fraaer-Tyra Site (20sa9)" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 50. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDY OF A LATE WOODLAND POPULATION FROM MICHIGAN: FRAZER-TYRA SITE (20SA9) by ALLISON JUNE MUHAMMAD DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2010 MAJOR: ANTHROPOLOGY (Archaeology) Approved by: Advisor Date © COPYRIGHT BY ALLISON JUNE MUHAMMAD 2010 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Bismillahi Rahmani Rahim Ashhadu alla ilaha illa-llahu wa Ashhadu anna Muhammadan abduhu wa rasuluh I would like to acknowledge my beautiful, energetic, loving daughters Bahirah, Laila, and Nadia. You have been my inspiration to complete this journey. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their kindness and their support. I would like to acknowledge the support and guidance of Dr. Mark Baskaran and Dr. Ed Van Hees of the WSU Geology department I would like to acknowledge the dedication and commitment of my dissertation committee to my success, particularly Dr. -

Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains Edited by George C

Tri-Services Cultural Resources Research Center USACERL Special Report 97/2 December 1996 U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction Engineering Research Laboratory Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort, with contributions by George C. Frison, Dennis L. Toom, Michael L. Gregg, John Williams, Laura L. Scheiber, George W. Gill, James C. Miller, Julie E. Francis, Robert C. Mainfort, David Schwab, L. Adrien Hannus, Peter Winham, David Walter, David Meyer, Paul R. Picha, and David G. Stanley A Volume in the Central and Northern Plains Archeological Overview Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 47 1996 Arkansas Archeological Survey Fayetteville, Arkansas 1996 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archeological and bioarcheological resources of the Northern Plains/ edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort; with contributions by George C. Frison [et al.] p. cm. — (Arkansas Archeological Survey research series; no. 47 (USACERL special report; 97/2) “A volume in the Central and Northern Plains archeological overview.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56349-078-1 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Great Plains—Antiquities. 2. Indians of North America—Anthropometry—Great Plains. 3. Great Plains—Antiquities. I. Frison, George C. II. Mainfort, Robert C. III. Arkansas Archeological Survey. IV. Series. V. Series: USA-CERL special report: N-97/2. E78.G73A74 1996 96-44361 978’.01—dc21 CIP Abstract The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Northwestern Great Plains states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota is reviewed here. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Bipolar Technology and Pebble Stone Artifacts

Bipolar Technology and Pebble Stone Artifacts: Experimentation in Stone Tool Manufacture A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department ofAnthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Bruce David Low Fall 1997 ( Copyright Bruce David Low, 1997. All rights reserved.) PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereoffor financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofAnthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 2AS) i ABSTRACT There is a general lack of research concerning the technological aspect of pebble stone artifacts throughout the Northern Plains. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 5 Number 2 2010/2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson Cathy L. Draeger-Williams Cathy A. Carson Wade T. Tharp Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy A. Carson, Records Check Coordinator Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. Mission Statement: The Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology promotes the conservation of Indiana’s cultural resources through public education efforts, financial incentives including several grant and tax credit programs, and the administration of state and federally mandated legislation. 2 For further information contact: Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology 402 W. Washington Street, Room W274 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2739 Phone: 317/232-1646 Email: [email protected] www.IN.gov/dnr/historic 2010/2011 3 Indiana Archaeology Volume 5 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors of articles were responsible for ensuring that proper permission for the use of any images in their articles was obtained. -

Hopewell Archeology: the Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997

Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997 1. Current Research at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park By Bret J. Ruby, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio Archeological research is an essential activity at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. An active program of field research provides the information necessary to protect and preserve Hopewellian archeological resources. The program also addresses a series of long-standing questions regarding the cultural history and adaptive strategies of Hopewellian populations in the central Scioto region. Presented below are preliminary notices of recent field projects conducted by park personnel with the assistance of the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska. These recent efforts are focused on three Hopewellian centers in Ross County. Two of these centers, the Mound City Group and the Hopeton Earthworks, are administered by the National Park Service as units of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. The third center, the Spruce Hill Works, is privately owned and is being considered for possible inclusion in the park. Research at the Mound City Group Work at the Mound City Group was prompted by plans to install a set of eight new interpretive signs along a trail encircling the mounds and earthworks at the site. Although the Mound City Group has been the focus of archeological investigations for almost 150 years, previous research has focused almost exclusively on the mounds and earthworks themselves (Figure 1), with little attention paid to identifying archeological resources that may lie just outside the earthwork walls. Figure 1. -

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions Summer 2018 2018 Adventure Zone Family Fun Center 218-740-4000 / www.adventurezoneduluth.com SUMMER HOURS: Memorial Day - Labor Day Sunday - Thursday: 11am – 10pm Friday & Saturday 11am - Midnight WINTER HOURS: Monday – Thursday: 3 – 9pm Friday & Saturday: 11am – Midnight Sunday: 11am – 9pm DESCRIPTION: “Canal Park’s fun and games from A to Z”. There is something for everyone! The Northland’s newest family attraction boasts over 50,000 square feet of fun, featuring multi-level laser tag, batting cages, mini golf, the largest video/redemption arcade in the area, Vertical Endeavors rock climbing walls, virtual sports challenge, a kid’s playground and more! Make us your party headquarters! RATES: Laser Zone: Laser Tag $6 North Shore Nine: Mini Golf $4 Sport Plays: Batting Cages or Virtual Sports Simulator $1.75 per play or 3 plays for $5 DIRECTIONS: Located in Duluth’s Canal Park Business District at 329 Lake Avenue South, just blocks from Downtown Duluth and the famous Aerial Lift Bridge. DEALS: Adventure Zone offers many Daily Deals and Weekly Specials. A sample of those would include the Ultra Adventure Pass for $17, a Jr. Adventure Pass for $11, Monday Fun Day, Ten Buck Tuesday, Thursday Family Night and a Late Night Special on Fri & Sat for $10! AMENITIES: Meeting and Banquet spaces available with catering options from local restaurants. 2018 Bentleyville “Tour of Lights” 218-740-3535 / www.bentleyvilleusa.org WINTER HOURS: November 17 – December 26, 2018 Sunday – Thursday: 5 - 9pm Friday & Saturday: 5 – 10pm DESCRIPTION: A non-profit, charitable organization that holds a free annual family holiday light show – complete with Santa, holiday music and fire pits for roasting marshmallows. -

Aquatic Synthesis for Voyageurs National Park

Aquatic Synthesis for Voyageurs National Park Information and Technology Report USGS/BRD/ITR—2003-0001 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Technical Report Series The Biological Resources Division publishes scientific and technical articles and reports resulting from the research performed by our scientists and partners. These articles appear in professional journals around the world. Reports are published in two report series: Biological Science Reports and Information and Technology Reports. Series Descriptions Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Information and Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 This series records the significant findings resulting These reports are intended for publication of book- from sponsored and co-sponsored research programs. length monographs; synthesis documents; compilations They may include extensive data or theoretical analyses. of conference and workshop papers; important planning Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard high-quality standards as their journal counterparts. operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manuals; and data compilations such as tables and bibliographies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high-quality standards as their journal counterparts. Copies of this publication are available from the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161 (1-800-553-6847 or 703-487-4650). Copies also are available to registered users from the Defense Technical Information Center, Attn.: Help Desk, 8725 Kingman Road, Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, Virginia 22060-6218 (1-800-225-3842 or 703-767-9050). An electronic version of this report is available on-line at: <http://www.cerc.usgs.gov/pubs/center/pdfdocs/ITR2003-0001.pdf> Front cover: Aerial photo looking east over Namakan Lake, Voyageurs National Park. -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Voyageurs National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Voyageurs National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2007/007 THIS PAGE: A geologist highlights a geologic contact during a Geologic Resource Evaluation scoping field trip at Voyageurs NP, MN ON THE COVER: Aerial view of Voyageurs NP, MN NPS Photos Voyageurs National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2007/007 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 June 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer- reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly- published newsletters.