Continuity, Contiguity, and the Modern Jewish Literary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Around the Point

Around the Point Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages, Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman, Ber Kotlerman and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5577-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5577-8 CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Around the Point .......................................................................................... 1 Hillel Weiss Medieval Languages and Literatures in Italy and Spain: Functions and Interactions in a Multilingual Society and the Role of Hebrew and Jewish Literatures ............................................................................... 17 Arie Schippers The Ashkenazim—East vs. West: An Invitation to a Mental-Stylistic Discussion of the Modern Hebrew Literature ........................................... -

A Hebrew Maiden, Yet Acting Alien

Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page i Reading Jewish Women Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page ii blank Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iii Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Reading Jewish Society Jewish Women IRIS PARUSH Translated by Saadya Sternberg Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com © 2004 by Brandeis University Press Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or me- chanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. Originally published in Hebrew as Nashim Korot: Yitronah Shel Shuliyut by Am Oved Publishers Ltd., Tel Aviv, 2001. This book was published with the generous support of the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, Inc., Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry through the support of the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment of Brandeis University, and the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute through the support of the Donna Sudarsky Memorial Fund. -

Ofra Yeglin, Ph

Ofra Yeglin, Ph. D. Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies Emory University Atlanta, GA, 30322 404-727-0414; [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Ph.D., Hebrew Literature, Tel Aviv University, with distinction Dissertation: Modern Classicism and Classical Modernism in Lea Goldberg`s Poetry 1988 M.A., Hebrew Literature, Tel Aviv University, with distinction Dissertation: The Early Prosodic Style of Yehuda Amichai, David Avidan, Nathan Zach 1985 B.A., Hebrew Literature and General Studies, Tel Aviv University, magna cum laude Honors and Awards 2013 TIJS Avans Fund for Faculty Research 2012 TIJS Avans Fund for Faculty Research 2011 Woodruff fund Travel Grant (NAPH, UCA) 2009 University Research Council Grant (for research project on Abba Kovner`s Modern Long Poems) – Emory University 2008-9 Woodruff Fund Travel Grant (for study in Israel - Abba Kovner`s archive)- Emory University 2008-9 Institute for Comparative and International Studies Travel Grant (to attend a conference in UCL, England) –emory University 2006 Visiting Scholar at the Artists' Residence, Herzelia Center for the Creative Arts, Israel 2000 The Faculty of Humanities Dean`s Prize for Excellence in Teaching. Tel-Aviv University, Israel 1998-9 Fellow/overseas visiting scholar, St. Johns College, University of Cambridge, England 1998-9 Visiting scholar, The Center for Modern Hebrew Studies, University of Cambridge, England 1997 “Yad Ha`Nadiv Rothschild Foundation” Grant (for a book publication), Jerusalem, Israel 1993 The Dov Sadan Fuondation Prize for Modern Hebrew Literature Excellence in Research, Israel 1986 The Dov Sadan Foundation Prize for Modern Hebrew Literature Excellence in Research, Israel 1984 The Shalom Aleichem Prize for best dissertation in the study of Hebrew Literature, Israel 2 Academic Appointments 2011- Associate Professor of Hebrew Language, Literature, Culture MESAS, Emory University 2004- Assistant Professor of Hebrew Language, Literature and Culture: Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, Emory University Core Faculty Member, the Rabbi Donald A. -

Agnon's Shaking Bridge and the Theology of Culture

5 Agnon’s Shaking Bridge and the Theology of Culture Jeffrey Saks Rabbeinu HaGadol, Rabbi Avraham yitzhak HaKo- hen Kook z″l . How close he drew me in! in his humility he was kind enough to read my story “Va- Hayah HeAkov LeMishor,” which was then still in manuscript. When he returned it to me, he said in these exact words: “this is a true Hebrew/Jewish sto- ry, flowing through the divine channels without any זהו סיפור עברי באמת נובע מן הצינורות בלא שום] ”barrier 1.[מחיצה “today’s reader is no longer content with reading for pleasure. He expects to find a new message in every work.” Hemdat replied: i didn’t come to answer the question “Where are you going?” though i do some- times answer the question “Where did you come from?” 2 1 Orthodox Forum 6.24.13.indb 143 6/24/13 4:49 PM 1 Jeffrey Saks in discussing the consumption of literature from an Orthodox Jewish perspective, and the writings of the greatest modern Hebrew author, Nobel laureate S. y. Agnon, as an exercise in examining the “theology of culture,” i assume tillich’s notion of “the religious dimension in many special spheres of man’s cultural activity . [which] is never absent in cultural creations even if they show no relation to religion in the narrower sense of the word.”3 the writings of S. y. Agnon (born as Shmuel yosef Czaczkes in buczacz, Galicia, 1887; died in israel, 1970),4 executed in a remarkably wide variety of genres, spanning an active career of over sixty years (with more volumes published posthumously than in his own life- time), are exemplars of the religious dimension embodied in literary creation. -

The Emancipation of Yiddish

DAVID G. ROSKIES The Emancipation of Yiddish THE STORY OF MODERN YIDDISH CULTURE reads likeone of its own fictions. As in a nineteenth-century dime novel, the plot begins in an East European shtetl, moves on to Berlin and the Bowery, with a climactic recognition scene in Stockholm and a denouement in, of all places, Oxford. As in Sholem Aleichem, it is a story of shattered hopes and ironic victories. As in Peretz, the leading characters are motivated by a search for transcendence, but their designs are frustrated by a profound generational crisis, as in any number of family sagas, or by vast demonic forces unleashed upon them when they are most vulner able, as in I. B. Singer. Finally, with due credit to Abramovitsh, the frame tale provides an analogical key to the main narrative. The tale describes a contest for cultural renewal. On one side is Hasidism, the last "major trend" in Jewish mysticism, laying exclusive claim to legitimacy, and opposing it from the West is the Enlighten ment. The Westernizers fail at direct confrontation but achieve ulti mate victory by a creative betrayal of Hasidism itself. The contest begins with Nahman ben Simha of Bratslav, the great . grandson of the Ba'al Shem Nahman's complex allegorical tales, harbingers, we are often told, of Kafka, chart the paradoxical and tragic course of tikkun, or cosmic restoration. In his most revealing as moment, Nahman comes across a Marrano, cut off from his people, from prayer and public observance, struggling to achieve a higher spiritual state in the treacherous world of politics. -

Dov Jarden Born 17 January 1911 (17 Tevet, Taf Resh Ain Aleph) Deceased 29 September 1986 (25 Elul, Taf Shin Mem Vav) by Moshe Jarden12

Dov Jarden Born 17 January 1911 (17 Tevet, Taf Resh Ain Aleph) Deceased 29 September 1986 (25 Elul, Taf Shin Mem Vav) by Moshe Jarden12 http://www.dov.jarden.co.il/ 1Draft of July 9, 2018 2The author is indebted to Gregory Cherlin for translating the original biography from Hebrew and for his help to bring the biography to its present form. 1 Milestones 1911 Birth, Motele, Russian Empire (now Motal, Belarus) 1928{1933 Tachkemoni Teachers' College, Warsaw 1935 Immigration to Israel; enrolls in Hebrew University, Jerusalem: major Mathematics, minors in Bible studies and in Hebrew 1939 Marriage to Haya Urnstein, whom he called Rachel 1943 Master's degree from Hebrew University 1943{1945 Teacher, Bnei Brak 1945{1955 Completion of Ben Yehuda's dictionary under the direction of Professor Tur-Sinai 1946{1959 Editor and publisher, Riveon LeMatematika (13 volumes) 1947{1952 Assisting Abraham Even-Shoshan on Milon Hadash, a new He- brew Dictionary 1953 Publication of two Hebrew Dictionaries, the Popular Dictionary and the Pocket Dictionary, with Even-Shoshan 1956 Doctoral degree in Hebrew linguistics from Hebrew Unversity, under the direction of Professor Tur-Sinai; thesis published in 1957 1960{1962 Curator of manuscripts collection, Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati 1965 Publication of the Dictionary of Hebrew Acronyms with Shmuel Ashkenazi 1966 Publication of the Complete Hebrew-Spanish Dictionary with Arye Comay 1966 Critical edition of Samuel HaNagid's Son of Psalms under the Hebrew Union College Press imprint 1969{1973 Critical edition of -

Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands

Out of the Shtetl Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands NANCY SINKOFF OUT OF THE SHTETL Program in Judaic Studies Brown University Box 1826 Providence, RI 02912 BROWN JUDAIC STUDIES Series Editors David C. Jacobson Ross S. Kraemer Saul M. Olyan Number 336 OUT OF THE SHTETL Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands by Nancy Sinkoff OUT OF THE SHTETL Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands Nancy Sinkoff Brown Judaic Studies Providence Copyright © 2020 by Brown University Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953799 Publication assistance from the Koret Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Brown Judaic Studies, Brown University, Box 1826, Providence, RI 02912. In memory of my mother Alice B. Sinkoff (April 23, 1930 – February 6, 1997) and my father Marvin W. Sinkoff (October 22, 1926 – July 19, 2002) CONTENTS Acknowledgments....................................................................................... ix A Word about Place Names ....................................................................... xiii List of Maps and Illustrations .................................................................... xv Introduction: -

Agnon TITLE PAGE

THE BOARD OF RABBIS OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA PRESENTS ONE PEOPLE, O NE BOOK 5768 Participating Conservative, Orthodox, Reconstructionist & Reform congregations Adat Ari El • Beth Chayim Chadashim • Beth Shir Sholom • Congregation Kol Ami Congregation Tikvat Jacob • IKAR • Kehillat Israel • Makom Ohr Shalom Malibu Jewish Center & Synagogue • Pasadena Jewish Temple & Center Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel • Temple Aliyah • Temple Beth Am Temple Beth Hillel • Temple Emanuel of Beverly Hills • Temple Israel of Hollywood Temple Kol Tikvah • Temple Ramat Zion • University Synagogue • Westwood Village Synagogue Dear One People, One Book Participant: Our tradition teaches that when even two people gather to study holy words, the presence of God dwells with them. We are pleased that so many of us will, over the course of the year, gather together to study words and ideas, learning from and with each other and our shared tradition. As we mark the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of medinat Yisrael (the state of Israel), we are honored to read and study selected works by S. Y. Agnon, the acclaimed genius of modern Hebrew literature. A Book That Was Lost and Other Stories is a collection of stories written by Agnon, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Agnon is a masterful maggid—a classic storyteller who weaves together Biblical and rabbinic sources, colorful images of the “old country,” and vivid insights on daily life in Israel. We hope that this sourcebook for A Book That Was Lost and Other Stories will help you to understand and appreciate the literary mastery of Shai Agnon. To guide your study and gain a fuller appreciation of the richness and complexity of the author, Rabbi Daniel Bouskila and Rabbi Miriyam Glazer have prepared essays on key aspects of Agnon’s work and thought. -

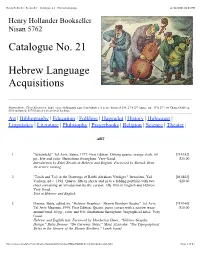

Hebrew Language 11/14/2005 04:01 PM

Henry Hollander, Bookseller - Catalogue 21 - Hebrew Language 11/14/2005 04:01 PM Henry Hollander Bookseller Nisan 5762 Catalogue No. 21 Hebrew Language Acquisitions Shown above, Three Klezmorim, hand-colored lithograph signed and numbered in an edition of 150, 23"x 29" (image size 19"x 25"), by Chaim Goldberg. $300 unframed; $375 framed with archival backing. Art | Bibliography | Education | Folklore | Haggadot | History | Holocaust | Linguistics | Literature | Philosophy | Prayerbooks | Religion | Science | Theater | ART 1. "Scheinfeld." Tel Aviv, Sabra, 1977. First Edition. Oblong quarto, orange cloth, 68 [#14152] pp., b/w and color illustrations throughout. Very Good. $25.00 Introduction by Ethel Broido in Hebrew and English. Foreword by Baruch Oren. An artist's catalog. 2. "Torah and Toil in the Drawings of Rabbi Abraham Verdiger." Jerusalem, Yad [#14802] Vashem, nd c. 1992. Quarto, fifteen sheets laid in to a folding portfolio with two $20.00 sheet containing an introduction by the curator, Elly Dlin in English and Hebrew. Very Good. Text in Hebrew and English. 3. Donner, Batia, edited by. "Hebrew Graphics - Shamir Brothers Studio." Tel Aviv, [#14140] Tel Aviv Museum, 1999. First Edition. Quarto, paper covers with a narrow wrap- $25.00 around band, 80 pp., color and b/w illustrations throughout, biographical notes. Very Good. Hebrew and English text. Foreword by Mordechai Omer.. "Hebrew Graphic Design," Batia Donner. "On Currency Notes," Maoz Azaryahu. "The Typographical Styles in the Oeuvre of the Shamir Brothers," Yanek Iontef. file:///Users/metafo/Polis/Clients/Henry%20Hollander/HOLLANDERCATS/Cat%2021/cat21.htm Page 1 of 63 Henry Hollander, Bookseller - Catalogue 21 - Hebrew Language 11/14/2005 04:01 PM 4. -

When Did Haskalah Begin? Establishing the Beginning of Haskalah Literature and the Definition of "Modernism" Downloaded From

When Did Haskalah Begin? Establishing the Beginning of Haskalah Literature and the Definition of "Modernism" Downloaded from BY MOSHE PELLI http://leobaeck.oxfordjournals.org/ When did modern Hebrew literature begin? Does its beginning coincide with the beginning of Haskalah literature? Is there a literary personality who signals the beginning of the new trends in modern Hebrew literature? These were some of the questions discussed by several literary historians in the early days of Haskalah historiography. For some time, such questions were frequently debated, but after a while, literary historians and critics apparently lost interest in them. The topic has recently been revisited by a few contemporary Haskalah scholars. The questions now being asked echo earlier themes, though more at Ohio State University Libraries on September 5, 2016 profound queries have emerged: What is "modern" in "modern Hebrew litera- ture", and how is "Hebrew modernism" defined? The most significant trend in Haskalah historiography has highlighted the elements, which distinguish Haskalah literature from the corpus of traditional Hebrew literature through the ages. Haskalah was considered to be new, modern and different. Proponents of this notion designated Haskalah as the beginning of modern Hebrew literature, while endeavouring to identify a major writer or group of writers who, to them, signal the beginning of Haskalah. There was, however, another trend, the major spokesman of which was Dov Sadan (and perhaps also, to some extent, Shmuel Werses, as discussed below). Sadan did not emphasise the distinctions between bodies of literature. Instead, he estab- lished different outlooks, which group together various types of literature and form a different concept of periodisation. -

Jewish Folk Literature

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Near Eastern Languages and Departmental Papers (NELC) Civilizations (NELC) 1999 Jewish Folk Literature Dan Ben-Amos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers Part of the Cultural History Commons, Folklore Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ben-Amos, D. (1999). Jewish Folk Literature. Oral Tradition, 14 (1), 140-274. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/93 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/93 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jewish Folk Literature Abstract Four interrelated qualities distinguish Jewish folk literature: (a) historical depth, (b) continuous interdependence between orality and literacy, (c) national dispersion, and (d) linguistic diversity. In spite of these diverging factors, the folklore of most Jewish communities clearly shares a number of features. The Jews, as a people, maintain a collective memory that extends well into the second millennium BCE. Although literacy undoubtedly figured in the preservation of the Jewish cultural heritage to a great extent, at each period it was complemented by orality. The reciprocal relations between the two thus enlarged the thematic, formal, and social bases of Jewish folklore. The dispersion of the Jews among the nations through forced exiles and natural migrations further expanded -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles History In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles History in the Public Courtroom: Commissions of Inquiry and Struggles over the History and Memory of Israeli Traumas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History by Nadav Gadi Molchadsky 2015 © Copyright by Nadav Gadi Molchadsky 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION History in the Public Courtroom: Commissions of Inquiry and Struggles over the History and Memory of Israeli Traumas by Nadav Gadi Molchadsky Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor David N. Myers, Co-Chair Professor Arieh B. Saposnik, Co-Chair This study seeks to shed new light on the complex web of relations among history, historiography and contemporary life. It does so by focusing on Israeli commissions of inquiry that have taken rise in the wake of major national traumas such as failed battles in the 1948 War, the Yom Kippur War, and the assassination of the Zionist leader Chaim Arlosoroff. Each one of these landmark events in the history of Israel was investigated by a state or a military commission of inquiry, whose members and audience operate as authors of history and agents of memory. The study suggests that commissions of inquiry, which have been studied to date primarily as legal, administrative, and political bodies, in fact also operate as a public historian of a unique kind. In this capacity, and unlike a professional historian, commissions are by definition expected not to refrain from making ethical and legal judgments. On the contrary, judgment is, in the final analysis, ii the underpinning motivation for their historical inquiry.