The Emancipation of Yiddish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yiddish Literature

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 1990 Yiddish Literature Ken Frieden Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Frieden, Ken, "Yiddish Literature" (1990). Religion. 39. https://surface.syr.edu/rel/39 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i C'L , IS4 ed l'ftOv\ Yiddish Literature 1077 וt..c:JI' $-- 131"'1+-" "r.כ) C fv כ,;E Yiddish Literature iddiSh literature may 00 said to have been born the Jews of northern Europe during this time than among twice. The earliest evidence of Yiddish literary ac non-Jews living in the same area. Many works achieved Y tivity dates from the 13th century and is found such popularity that they were frequently reprinted over in southern Germany, where the language itself had origi a period of centuries and enjoyed an astonishingly wide nated as a specifically Jewish variant of Middle High Ger dissemination, with the result that their language devel man approximately a quarter of a millennium earlier. The oped into an increasingly ossified koine that was readily Haskalah, the Jewish equivalent of the Enlightenment, understood over a territory extending from Amsterdam to effectively doomed the Yiddish language and its literary Odessa and from Venice to Hamburg. During the 18th culture in Germany and in western Europe during the century the picture changed rapidly in western Europe, course of the 18th century. -

Around the Point

Around the Point Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages, Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman, Ber Kotlerman and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5577-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5577-8 CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Around the Point .......................................................................................... 1 Hillel Weiss Medieval Languages and Literatures in Italy and Spain: Functions and Interactions in a Multilingual Society and the Role of Hebrew and Jewish Literatures ............................................................................... 17 Arie Schippers The Ashkenazim—East vs. West: An Invitation to a Mental-Stylistic Discussion of the Modern Hebrew Literature ........................................... -

A Hebrew Maiden, Yet Acting Alien

Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page i Reading Jewish Women Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page ii blank Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iii Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Reading Jewish Society Jewish Women IRIS PARUSH Translated by Saadya Sternberg Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com © 2004 by Brandeis University Press Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or me- chanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. Originally published in Hebrew as Nashim Korot: Yitronah Shel Shuliyut by Am Oved Publishers Ltd., Tel Aviv, 2001. This book was published with the generous support of the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, Inc., Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry through the support of the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment of Brandeis University, and the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute through the support of the Donna Sudarsky Memorial Fund. -

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin

Marina Dmitrieva* Traces of Transit Jewish Artists from Eastern Europe in Berlin In the 1920s, Berlin was a hub for the transfer of culture between East- ern Europe, Paris, and New York. The German capital hosted Jewish art- ists from Poland, Russia, and Ukraine, where the Kultur-Liga was found- ed in 1918, but forced into line by Soviet authorities in 1924. Among these artists were figures such as Nathan Altman, Henryk Berlewi, El Lissitzky, Marc Chagall, and Issachar Ber Ryback. Once here, they be- came representatives of Modernism. At the same time, they made origi- nal contributions to the Jewish renaissance. Their creations left indelible traces on Europe’s artistic landscape. But the idea of tracing the curiously subtle interaction that exists between the concepts “Jewish” and “mod- ern”... does not seem to me completely unappealing and pointless, especially since the Jews are usually consid- ered adherents of tradition, rigid views, and convention. Arthur Silbergleit1 The work of East European Jewish artists in Germany is closely linked to the question of modernity. The search for new possibilities of expression was especially relevant just before the First World War and throughout the Weimar Republic. Many Jewish artists from Eastern Europe passed through Berlin or took up residence there. One distinguish- ing characteristic of these artists was that on the one hand they were familiar with tradi- tional Jewish forms of life due to their origins; on the other hand, however, they had often made a radical break with this tradition. Contemporary observers such as Kurt Hiller characterised “a modern Jew” at that time as “intellectual, future-oriented, and torn”.2 It was precisely this quality of being “torn” that made East European artists and intellectuals from Jewish backgrounds representative figures of modernity. -

Yiddish Modernism and German Modernity in the Weimar

Modern Yiddish literature poses a challenge to any model of a secular culture, because this literature is never secular as a static condi- tion, but always secularizing, poised between centripetal references to the Jewish tradition and centrifugal aspirations toward the world beyond. This tension is a consequence of Yiddish’s linguistic character and its function in pre-modern Jewish life as a “fusion language” —that is, a language that consists of several otherwise unrelated linguistic sources (like English!). Yiddish brings together a Hebrew al- Yiddish Modernism phabet and liturgical rhetoric with a Germanic grammar and vocabulary, as well as Slavic and German terminology and syntactic structures. Thus it is simultaneously rooted in a Jewish tradition Modernity in the of textual study and in the Eastern European Weimar Era society to which its speakers trace their origins. By extension, Yiddish literature emerges in the Middle Ages and Renaissance out of a Marc Caplan mediating function, alternately translating sacred Hebrew texts, such as biblical stories or rabbinic legends, into the vernacular language and expectations of its readers, or translating and transforming non-Jewish literature into a Judaic language and worldview. Starting in the 19th century, modern Jewish writers used Yid- dish literature to challenge the norms of Jewish society via the rhetoric of Talmudic learning and the Slavic marketplace. These typically satirical works introduced modern ideals via a camouflage of familiar, parodic rhetorical devices that captured the location of Jewish so- ciety between tradition and modernity, as well as the contradictions of a secretly polemical, outwardly conventional literary discourse. The Yiddish literature produced in Weimar-era Berlin is a provocative example of how Yiddish writers dedicated themselves to a secularizing ideology and aesthetic while remaining bound to traditional habits of Jewish rhetoric, reference, and sensibility. -

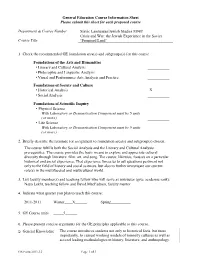

Slavic Lang M98T GE Form

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Slavic Languages/Jewish Studies M98T Crisis and War: the Jewish Experience in the Soviet Course Title ‘Promised Land’ 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course fulfills both the Social Analysis and the Literary and Cultural Analysis prerequisites. The course provides the basic means to explore and appreciate cultural diversity through literature, film, art, and song. The course, likewise, focuses on a particular historical and social experience. That experience forces us to ask questions pertinent not only to the field of history and social sciences, but also to further investigate our current role(s) in the multifaceted and multicultural world. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Naya Lekht, teaching fellow and David MacFadyen, faculty mentor 4. Indicate what quarter you plan to teach this course: 2011-2011 Winter____X______ Spring__________ 5. GE Course units _____5______ 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. General Knowledge The course introduces students not only to historical facts, but more importantly, to current working models of minority cultures as well as several leading methodologies in history, literature, and anthropology. -

Reader's Guide

a reader’s guide to The World to Come by Dara Horn Made possible by The Deschutes Public Library Foundation, Inc. and The Starview Foundation, ©2008 1 A Novel Idea: Celebrating Five Years 2 Author Dara Horn 3 That Picture. That Cover. 5 Discussion Questions 7 The Russian Pogroms & Jewish Immigration to America 9 Marc Chagall 12 Der Nister 15 Yiddish Fiction Overview 19 Related Material 26 Event Schedule A Novel Idea celebrating five years A Novel Idea ... Read Together celebrates five years of success and is revered as the leading community read program in Oregon. Much of our success is due to the thousands of Deschutes County residents who embrace the program and participate actively in its free cultural events and author visits every year. Through A Novel Idea, we’ve trekked across the rivers and streams of Oregon with David James Duncan’s classic The River Why, journeyed to the barren and heart-breaking lands of Afghanistan through Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, trucked our way through America and Mexico with María Amparo Escandón’s González and Daughter Trucking Co., and relived the great days of Bill Bowerman’s Oregon with Kenny Moore’s book Bowerman and the Men of Oregon. This year, we enter The World to Come with award-winning author Dara Horn and are enchanted by this extraordinary tale of mystery, folklore, theology, and history. A month-long series of events kicks off on Saturday, April 1 26 with the Obsidian Opera performing songs from Fiddler on the Roof. More than 20 programs highlight this year’s book at the public libraries in Deschutes County including: Russian Jewish immigrant experience in Oregon, the artist Marc Chagall, Jewish baking, Judaism 101, art workshops, a Synagogue tour, and book discussions—all inspired from the book’s rich tale. -

Ofra Yeglin, Ph

Ofra Yeglin, Ph. D. Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies Emory University Atlanta, GA, 30322 404-727-0414; [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Ph.D., Hebrew Literature, Tel Aviv University, with distinction Dissertation: Modern Classicism and Classical Modernism in Lea Goldberg`s Poetry 1988 M.A., Hebrew Literature, Tel Aviv University, with distinction Dissertation: The Early Prosodic Style of Yehuda Amichai, David Avidan, Nathan Zach 1985 B.A., Hebrew Literature and General Studies, Tel Aviv University, magna cum laude Honors and Awards 2013 TIJS Avans Fund for Faculty Research 2012 TIJS Avans Fund for Faculty Research 2011 Woodruff fund Travel Grant (NAPH, UCA) 2009 University Research Council Grant (for research project on Abba Kovner`s Modern Long Poems) – Emory University 2008-9 Woodruff Fund Travel Grant (for study in Israel - Abba Kovner`s archive)- Emory University 2008-9 Institute for Comparative and International Studies Travel Grant (to attend a conference in UCL, England) –emory University 2006 Visiting Scholar at the Artists' Residence, Herzelia Center for the Creative Arts, Israel 2000 The Faculty of Humanities Dean`s Prize for Excellence in Teaching. Tel-Aviv University, Israel 1998-9 Fellow/overseas visiting scholar, St. Johns College, University of Cambridge, England 1998-9 Visiting scholar, The Center for Modern Hebrew Studies, University of Cambridge, England 1997 “Yad Ha`Nadiv Rothschild Foundation” Grant (for a book publication), Jerusalem, Israel 1993 The Dov Sadan Fuondation Prize for Modern Hebrew Literature Excellence in Research, Israel 1986 The Dov Sadan Foundation Prize for Modern Hebrew Literature Excellence in Research, Israel 1984 The Shalom Aleichem Prize for best dissertation in the study of Hebrew Literature, Israel 2 Academic Appointments 2011- Associate Professor of Hebrew Language, Literature, Culture MESAS, Emory University 2004- Assistant Professor of Hebrew Language, Literature and Culture: Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, Emory University Core Faculty Member, the Rabbi Donald A. -

Agnon's Shaking Bridge and the Theology of Culture

5 Agnon’s Shaking Bridge and the Theology of Culture Jeffrey Saks Rabbeinu HaGadol, Rabbi Avraham yitzhak HaKo- hen Kook z″l . How close he drew me in! in his humility he was kind enough to read my story “Va- Hayah HeAkov LeMishor,” which was then still in manuscript. When he returned it to me, he said in these exact words: “this is a true Hebrew/Jewish sto- ry, flowing through the divine channels without any זהו סיפור עברי באמת נובע מן הצינורות בלא שום] ”barrier 1.[מחיצה “today’s reader is no longer content with reading for pleasure. He expects to find a new message in every work.” Hemdat replied: i didn’t come to answer the question “Where are you going?” though i do some- times answer the question “Where did you come from?” 2 1 Orthodox Forum 6.24.13.indb 143 6/24/13 4:49 PM 1 Jeffrey Saks in discussing the consumption of literature from an Orthodox Jewish perspective, and the writings of the greatest modern Hebrew author, Nobel laureate S. y. Agnon, as an exercise in examining the “theology of culture,” i assume tillich’s notion of “the religious dimension in many special spheres of man’s cultural activity . [which] is never absent in cultural creations even if they show no relation to religion in the narrower sense of the word.”3 the writings of S. y. Agnon (born as Shmuel yosef Czaczkes in buczacz, Galicia, 1887; died in israel, 1970),4 executed in a remarkably wide variety of genres, spanning an active career of over sixty years (with more volumes published posthumously than in his own life- time), are exemplars of the religious dimension embodied in literary creation. -

Continuity, Contiguity, and the Modern Jewish Literary

Dan Miron. From Continuity to Contiguity: Toward a New Jewish Literary Thinking. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010. 560 pp. $65.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8047-6200-7. Reviewed by Itay Zutra Published on H-Judaic (November, 2011) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) Dan Miron’s From Continuity to Contiguity: homogenous aspects of Jewish literature stretch‐ Toward a New Literary Jewish Thinking is a mas‐ ing from the Bible to modern times and tran‐ terpiece of literary and cultural analysis. The se‐ scending geographical, cultural, and linguistic nior Israeli critic and historian of Hebrew and boundaries. Miron’s pluralistic notion of contigui‐ Yiddish literature from Columbia University aims ty tries to bypass the continuity fallacy so that in‐ high: to introduce new theory to the study of mod‐ stead of looking at what connects Jewish litera‐ ern Jewish literature in all languages. It might be ture one should pay attention to what separates asked, why write such a monumental book in a and discontinues it. postmodern era engaged in deconstruction, disin‐ Miron’s journey towards literary contiguity tegration, and hybridity? It seems that the time begins in a thorough--one would even argue too for positivistic definite histories of literature is thorough--polemic with previous generations of long gone. Miron admits that a book such as his scholars who may have little to say to contempo‐ has not been written in any language for the last rary readers. The writings of the Israeli critics few decades. The book laments the disappearance Dov Sadan (1902-89), Barukh Kurzweil (1907-72), of strong meta-narratives while at the same time and Shimon Halkin (1889-87) and the Yiddish crit‐ rejecting them. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . he b r e W pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s & gr a p h i C ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y We d n e s d a y , oC t o b e r 27t h , 2010 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 315 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS & GRA P HIC ART Including: German, Haskallah and Related Books from the Library of the late Philosopher, Prof. Steven S. Schwarzschild Exceptional Rabbinic Autograph Letters: A Private Collection American-Judaica from the Library of Gratz College (Part II) Featuring: Talmudic Leaves. Guadalajara, 1480. * Machzor. Soncino, 1486. Spinoza, Opera Posthuma. Amsterdam, 1677. Judah Monis, Grammar of the Hebrew Tongue. Boston, 1735. The Toulouse Hagadah, 1941. Extensive Kabbalistic Manuscript Prayer-Book, 1732. Manuscript Kethubah. Peoria, Illinois, 1861. ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Wednesday, 27th October, 2010 at 1:00 pm precisely (NOTE EARLIER TIME) ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 24th October - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 25th October - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 26th October - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm NO VIEWING ON THE DAY OF SALE This Sale may be referred to as: “Agatti” Sale Number Forty-Nine Illustrated Catalogues: $35 (US) * $42 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . -

Dov Jarden Born 17 January 1911 (17 Tevet, Taf Resh Ain Aleph) Deceased 29 September 1986 (25 Elul, Taf Shin Mem Vav) by Moshe Jarden12

Dov Jarden Born 17 January 1911 (17 Tevet, Taf Resh Ain Aleph) Deceased 29 September 1986 (25 Elul, Taf Shin Mem Vav) by Moshe Jarden12 http://www.dov.jarden.co.il/ 1Draft of July 9, 2018 2The author is indebted to Gregory Cherlin for translating the original biography from Hebrew and for his help to bring the biography to its present form. 1 Milestones 1911 Birth, Motele, Russian Empire (now Motal, Belarus) 1928{1933 Tachkemoni Teachers' College, Warsaw 1935 Immigration to Israel; enrolls in Hebrew University, Jerusalem: major Mathematics, minors in Bible studies and in Hebrew 1939 Marriage to Haya Urnstein, whom he called Rachel 1943 Master's degree from Hebrew University 1943{1945 Teacher, Bnei Brak 1945{1955 Completion of Ben Yehuda's dictionary under the direction of Professor Tur-Sinai 1946{1959 Editor and publisher, Riveon LeMatematika (13 volumes) 1947{1952 Assisting Abraham Even-Shoshan on Milon Hadash, a new He- brew Dictionary 1953 Publication of two Hebrew Dictionaries, the Popular Dictionary and the Pocket Dictionary, with Even-Shoshan 1956 Doctoral degree in Hebrew linguistics from Hebrew Unversity, under the direction of Professor Tur-Sinai; thesis published in 1957 1960{1962 Curator of manuscripts collection, Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati 1965 Publication of the Dictionary of Hebrew Acronyms with Shmuel Ashkenazi 1966 Publication of the Complete Hebrew-Spanish Dictionary with Arye Comay 1966 Critical edition of Samuel HaNagid's Son of Psalms under the Hebrew Union College Press imprint 1969{1973 Critical edition of