Jewish Folk Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Unpacking the Book #12The Tabernacle

The W.E.L.L. Stoneybrooke Christian Schools Sherry L. Worel www.sherryworel.com 2012.UTB.12 Unpacking the Book #12The Tabernacle I. An overview There are nearly 470 verses in our bible used to describe the form and furnishings of the Tabernacle and Temple. The bible gives a very specific plan for the building of the tabernacle. However, the temple is not outlined in detail. I Chron. 28:11‐19 does seem to indicate that the Lord gave David some sort of plan or model. The tabernacle was an ornate tent shrine that served the people of Israel for approximately 200 years until it was replaced by Solomon’s temple. This temple served as God’s home for approximately 400 years until the Babylonians destroyed it in 586 BC. When the Israelites returned from Babylon, Zerubbabel over saw the rebuilding of a much inferior temple in 520 BC. This building was damaged and repaired many times until Herod built his “renovation” in 19 BC. The Roman General, Titus destroyed this temple in 70AD. II. The Tabernacle (The Tent of Meeting or Place of Dwelling) A. Consider the New Testament perspective: Hebrews 9:9‐11, 10:1, Col. 2:17 and Revelation 15:5, 21:3 B. Moses was given a model of this meeting house by God Himself (Ex. 25:40) C. The craftsmen Bezalel and Oholiab built this ornate tent. See Ex. 25‐27, 35‐40 for all the details. 1. There was a linen fence that formed an outer courtyard. In that courtyard were two furnishings: a. -

Talmud Tales Ruth Calderon Copyrighted Material Translated by Ilana Kurshan

A Bride for One Night Talmud Tales Ruth Calderon Copyrighted Material Translated by Ilana Kurshan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION xi THE IMAGINATIVE MAP xvii The Fishpond 1 Sisters 7 The Other Side 15 Beloved Rabbi 31 Libertina 39 Return 49 A Bride for One Night 57 Nazir 67 Lamp 75 The Matron 85 The Goblet 91 The Knife 99 He and His Son 105 Sorrow in the Cave 115 Elisha 123 The Beruria Incident 133 Yishmael, My Son, Bless Me 139 NOTES 145 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 159 Buy the book A Bride for One Night Talmud Tales Ruth Calderon Copyrighted Material Translated by Ilana Kurshan INTRODUCTION In this book I retell stories from the Talmud and midrash that are close to my heart, to introduce them to those who, like me, did not grow up with them. I do not cast these tales in an educational, religious, or aca- demic light but, rather, present them as texts that have the power to move people. That is, I present them as literature. The Talmud contains hundreds of stories about rabbinic sages and other historical fi gures who lived during the late Second Temple and rabbinic periods, which spanned the fi rst few centuries of the Common Era. The stories were recorded long after the events they recount, and thus they are literary rather than historical accounts. For generations these stories were neglected by literary audiences and were considered the province of rabbis and academics alone. But this is no longer the case. In the past decades readers of diverse backgrounds have devel- oped an openness and a willingness to engage this literature on their own terms. -

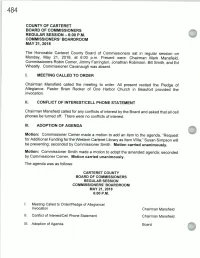

Chairman Mansfield Called for Any Conflicts of Interest by the Board and Asked That All Cell Phones Be Turned Off

COUNTY OF CARTERET BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS REGULAR SESSION — 6: 00 P. M. COMMISSIONERS' BOARDROOM MAY 21, 2018 The Honorable Carteret County Board of Commissioners sat in regular session on Monday, May 21, 2018, at 6: 00 p. m. Present were: Chairman Mark Mansfield, Commissioners Robin Comer, Jimmy Farrington, Jonathan Robinson, Bill Smith, and Ed Wheatly. Commissioner Cavanaugh was absent. I. MEETING CALLED TO ORDER Chairman Mansfield called the meeting to order. All present recited the Pledge of Allegiance. Pastor Brian Recker of One Harbor Church in Beaufort provided the invocation. II. CONFLICT OF INTEREST/CELL PHONE STATEMENT Chairman Mansfield called for any conflicts of interest by the Board and asked that all cell phones be turned off. There were no conflicts of interest. III. ADOPTION OF AGENDA Motion: Commissioner Comer made a motion to add an item to the agenda, " Request for Additional Funding for the Western Carteret Library as Item Villa-,"Susan Simpson will be presenting; seconded by Commissioner Smith. Motion carried unanimously. Motion: Commissioner Smith made a motion to adopt the amended agenda; seconded by Commissioner Comer. Motion carried unanimously. The agenda was as follows: CARTERET COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS REGULAR SESSION COMMISSIONERS' BOARDROOM MAY 21, 2018 6: 00 P. M. Meeting Called to Order/Pledge of Allegiance/ Invocation Chairman Mansfield II. Conflict of Interest/ Cell Phone Statement Chairman Mansfield III. Adoption of Agenda Board IV. Consent Agenda Board 1. Approval of Minutes March 19, 2018 April 16, 2018 2. Tax Releases and Refunds a. Tax Releases Under $ 100 b. Tax Releases Over $ 100 C. Tax Refunds Under $ 100 d. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Fooling the Tax Collector

Schachter, rosh yeshiva of Rabbi Isaac Elchanan In introducing a new metaphor — that Theological Seminary (RIETS) at Yeshiva citizens of a modern democracy are more University. “It is important to note that today like partners than subjects — into formalized the basis for taxation is totally different from Jewish legal thinking, Schachter has taken what it was in talmudic times.” According to a a first important step in opening up an en- contemporary understanding of Jewish law, we tirely new vista from which to think about ought to ground the obligation to pay taxes not the legitimacy of taxes and the responsibility SHMA.COM in the anachronistic notion of dina d’malchuta of partners to participate in public policy dis- dina; rather, we should invoke the talmudic cussions. In this alternative view, it is not us concept of shutfim or partnership. Schachter versus them, but rather “we the people” who concludes, “All people who live in the same must formulate fair tax rules and just public city, state, and country are considered ‘shut- policies. It follows directly from Schachter’s fim’ with respect to the services provided by new formulation that as Jewish partners in that city, state, and country. The purpose be- this process, we have a unique right and obli- hind the taxes is no longer ‘to enrich the king’ gation to bring to our fellow citizens the best in the slightest.” (Torahweb.org) of Jewish legal and ethical thinking. Fooling the Tax Collector: Why the Rabbis Once Approved DAVID BRODSKY abbi Naftali Tzvi Weisz, the Spinka Luke 3:12, 5:27–30, 7:29, 7:34, 15:1, and 18:9– Rebbe of Boro Park, and the great-great- 14), just as the Mishnah associates them with Rgrandson of R. -

A Theological Reading of the Gideon-Abimelech Narrative

YAHWEH vERsus BAALISM A THEOLOGICAL READING OF THE GIDEON-ABIMELECH NARRATIVE WOLFGANG BLUEDORN A thesis submitted to Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts & Humanities April 1999 ABSTRACT This study attemptsto describethe contribution of the Abimelech narrative for the theologyof Judges.It is claimedthat the Gideonnarrative and the Abimelechnarrative need to be viewed as one narrative that focuseson the demonstrationof YHWH'S superiority over Baalism, and that the deliverance from the Midianites in the Gideon narrative, Abimelech's kingship, and the theme of retribution in the Abimelech narrative serve as the tangible matter by which the abstracttheological theme becomesnarratable. The introduction to the Gideon narrative, which focuses on Israel's idolatry in a previously unparalleled way in Judges,anticipates a theological narrative to demonstrate that YHWH is god. YHwH's prophet defines the general theological background and theme for the narrative by accusing Israel of having abandonedYHwH despite his deeds in their history and having worshipped foreign gods instead. YHWH calls Gideon to demolish the idolatrous objects of Baalism in response, so that Baalism becomes an example of any idolatrous cult. Joash as the representativeof Baalism specifies the defined theme by proposing that whichever god demonstrateshis divine power shall be recognised as god. The following episodesof the battle against the Midianites contrast Gideon's inadequateresources with his selfish attempt to be honoured for the victory, assignthe victory to YHWH,who remains in control and who thus demonstrateshis divine power, and show that Baal is not presentin the narrative. -

Jewish Folk Literature

Oral Tradition, 14/1 (1999): 140-274 Jewish Folk Literature Dan Ben-Amos For Batsheva Four interrelated qualities distinguish Jewish folk literature: (a) historical depth, (b) continuous interdependence between orality and literacy, (c) national dispersion, and (d) linguistic diversity. In spite of these diverging factors, the folklore of most Jewish communities clearly shares a number of features. The Jews, as a people, maintain a collective memory that extends well into the second millennium BCE. Although literacy undoubtedly figured in the preservation of the Jewish cultural heritage to a great extent, at each period it was complemented by orality. The reciprocal relations between the two thus enlarged the thematic, formal, and social bases of Jewish folklore. The dispersion of the Jews among the nations through forced exiles and natural migrations further expanded the themes and forms of their folklore. In most countries Jews developed new languages in which they spoke, performed, and later wrote down their folklore. As a people living in diaspora, Jews incorporated the folklore of other nations while simultaneously spreading their own internationally known themes among the same nations. Although this reciprocal process is basic to the transmission of folklore among all nations, it occurred more intensely among the Jews, even when they lived in antiquity in the Land of Israel. Consequently there is no single period, no single country, nor any single language that can claim to represent the authentic composite Jewish folklore. The earliest known periods of Jewish folklore are no more genuine, in fact, than the later periods, with the result that no specific Jewish ethnic group’s traditions can be considered more ancient or more JEWISH FOLK LITERATURE 141 authentic than those of any of the others.1 The Biblical and Post-Biblical Periods Folklore in the Hebrew Bible Descriptions of Storytelling and Singing The Hebrew Bible describes both the spontaneous and the institutionalized commemoration of historical events. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hanne Trautner-Kromann n this introduction I want to give the necessary background information for understanding the nine articles in this volume. II start with some comments on the Hebrew or Jewish Bible and the literature of the rabbis, based on the Bible, and then present the articles and the background information for these articles. In Jewish tradition the Bible consists of three main parts: 1. Torah – Teaching: The Five Books of Moses: Genesis (Bereshit in Hebrew), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vajikra), Numbers (Bemidbar), Deuteronomy (Devarim); 2. Nevi’im – Prophets: (The Former Prophets:) Joshua, Judges, Samuel I–II, Kings I–II; (The Latter Prophets:) Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezek- iel; (The Twelve Small Prophets:) Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephania, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; 3. Khetuvim – Writings: Psalms, Proverbs, Job, The Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles I–II1. The Hebrew Bible is often called Tanakh after these three main parts: Torah, Nevi’im and Khetuvim. The Hebrew Bible has been interpreted and reinterpreted by rab- bis and scholars up through the ages – and still is2. Already in the Bible itself there are examples of interpretation (midrash). The books of Chronicles, for example, can be seen as a kind of midrash on the 10 | From Bible to Midrash books of Samuel and Kings, repeating but also changing many tradi- tions found in these books. In talmudic times,3 dating from the 1st to the 6th century C.E.(Common Era), the rabbis developed and refined the systems of interpretation which can be found in their literature, often referred to as The Writings of the Sages.