The Once and Future King: Utopianism As Political Practice in Indonesia El Pasado Y Futuro Rey: Utopismo Como Práctica Política En Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Indonesia: the Unlikely Nation?

History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page i A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Series Editor: Milton Osborne Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of eight books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979 and now in its eighth edition, and, most recently, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, published in 2000. History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA THE UNLIKELY NATION? Colin Brown History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iv First published in 2003 Copyright © Colin Brown 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Brown, Colin, A short history of Indonesia : the unlikely nation? Bibliography. -

Religion, Imperialism, and Resistance in Nineteenth Century's

Religion, Imperialism, and Resistance in Nineteenth Century’s 11 Jurnal Kajian Wilayah, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2010, Hal. 119-140 © 2010 PSDR LIPI ISSN 021-4534-555 Religion, Imperialism, and Resistance in Nineteenth Century’s Netherlands Indies and Spanish Philippines Muhamad Ali2 Abstrak Artikel ini menjelaskan bagaimana agama berfungsi sebagai pembenar imperialisme dan antiimperialisme, dengan mengkaji kekuatan imperialis Belanda di Hindia Belanda dan imperialis Spanyol di Filipina pada abad XIX. Pemerintah Kolonial Belanda tidaklah seberhasil pemerintah kolonial Spanyol dalam menjadikan jajahan mereka menjadi bangsa seperti mereka, meskipun agama digunakan sebagai alat dominasi. Bagi Spanyol, agama Katolik menjadi bagian peradaban mereka, dan menjadi bagian penting proyek kolonialisme mereka, sedangkan bagi pemerintah kolonial Belanda, agama Kristen tidak menjadi bagian penting kolonialisme mereka (kenyataan sejarah yang menolak anggapan umum di Indonesia bahwa kolonialisme Belanda dan kristenisasi sangat berhubungan). Misionaris Spanyol di Filipina menguasai daerah koloni melalui metode-metode keagamaan dan kebudayaan, sedangkan pemerintah kolonial Belanda, dan misionaris dari Belanda, harus berurusan dengan masyarakat yang sudah memeluk Islam di daerah-daerah Indonesia. Pemerintah Belanda mengizinkan kristenisasi dalam beberapa kasus asalkan tidak mengganggu umat Islam dan tidak mengganggu kepentingan ekonomi mereka.Akibatnya, mayoritas Filipina menjadi Katolik, sedangkan mayoritas Hindia Belanda tidak menjadi Protestan. Di sisi lain, agama -

Language, Literature and Society

LANGUAGE LITERATURE & SOCIETY with an Introductory Note by Sri Mulyani, Ph.D. Editor Harris Hermansyah Setiajid Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters Universitas Sanata Dharma 2016 Language, Li ter atu re & Soci ety Copyright © 2016 Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters Universitas Sanata Dharma Published by Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters Universitas Sanata Dharma Jl. Affandi, Mrican Yogyakarta 55281. Telp. (0274) 513301, 515253 Ext.1324 Editor Harris Hermansyah Setiajid Cover Design Dina Febriyani First published 2016 212 pages; 165 x 235 mm. ISBN: 978-602-602-951-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 2 | Language, Literature, and Society Contents Title Page........................................................................................... 1 Copyright Page ..................................................................................... 2 Contents ............................................................................................ 3 Language, Literature, and Society: An Introductory Note in Honor of Dr. Fr. B. Alip Sri Mulyani ......................................................................................... 5 Phonological Features in Rudyard Kipling‘s ―If‖ Arina Isti‘anah .................................................................................... -

J. Noorduyn Bujangga Maniks Journeys Through Java; Topographical Data from an Old Sundanese Source

J. Noorduyn Bujangga Maniks journeys through Java; topographical data from an old Sundanese source In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 138 (1982), no: 4, Leiden, 413-442 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 01:16:49AM via free access J. NOORDUYN BUJANGGA MANIK'S JOURNEYS THROUGH JAVA: TOPOGRAPHICAL DATA FROM AN OLD SUNDANESE SOURCE One of the precious remnants of Old Sundanese literature is the story of Bujangga Manik as it is told in octosyllabic lines — the metrical form of Old Sundanese narrative poetry — in a palm-leaf MS kept in the Bodleian Library in Oxford since 1627 or 1629 (MS Jav. b. 3 (R), cf. Noorduyn 1968:460, Ricklefs/Voorhoeve 1977:181). The hero of the story is a Hindu-Sundanese hermit, who, though a prince (tohaari) at the court of Pakuan (which was located near present-day Bogor in western Java), preferred to live the life of a man of religion. As a hermit he made two journeys from Pakuan to central and eastern Java and back, the second including a visit to Bali, and after his return lived in various places in the Sundanese area until the end of his life. A considerable part of the text is devoted to a detailed description of the first and the last stretch of the first journey, i.e. from Pakuan to Brëbës and from Kalapa (now: Jakarta) to Pakuan (about 125 lines out of the total of 1641 lines of the incomplete MS), and to the whole of the second journey (about 550 lines). -

Land- En Volkenkunde

Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal- , Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (The University of Sydney) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) volume 313 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ vki Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Singing is a Medicine By Wim van Zanten LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY- NC- ND 4.0 license, which permits any non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by- nc- nd/ 4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Front: angklung players in Kadujangkung, Kanékés village, 15 October 1992. Back: players of gongs and xylophone in keromong ensemble at circumcision festivities in Cicakal Leuwi Buleud, Kanékés, 5 July 2016. Translations from Indonesian, Sundanese, Dutch, French and German were made by the author, unless stated otherwise. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020045251 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Tafsir Dakwah Dalam Kidung Pangiling

“Volume 14, No.12, Juni 2020” TAFSIR DAKWAH DALAM KIDUNG PANGILING Oleh: Miftakhur Ridlo Institut Agama Islam Uluwiyah Mojokerto, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract: In a broad outline, the interpretation of Da'wah in Kidung Pangiling by Imam Malik includes 4 types. They are about the creed or faith, sharia or worship, morals and culture. The following is a song about faith: “2006 luweh gede tekane bendu Ilang imane syetan ketemu Rusak ikhlase ramene padu Ilmu amale syetan seng digugu”. It has meaning that in 2006 there were greater trials that came, the loss of faith and meeting with shaitan, the loss of sincerity and the fight, the use of demonic science. The next one is a song about sharia: “Syahadat limo sing di ugemi Satriyo piningit yo imam Mahdi Ngetrapno hukum lewat kitab kang suci Sing ora pisah dawuhe nabi”. The meaning of that song is the five creeds is held, Satria Piningit O Imam Mahdi, carrying out the law through the scripture, which will not be separated from the words of the Prophet. Furthermore a song about morals: “Mulo sedulur kudu seng akeh syukure Marang wong kuno tumprap bahasane Anane pepeling sing supoyo ati – ati uripe Cak biso selamet ndunyo akhirate”. It has meaning that you have to be thankful, speak delicately with parents, reminders to be careful, become able to survive the afterlife. The last is a song about culture: “Negoro Ngastino wis kompak banget Nyusun kekuatan supoyo menang lan selamet Negoro Ngamarto supoyo ajur lan memet Ngedu pendowo sampek dadi gemet”. That meaning is Ngastino have jointly arranged forces to win and survive. -

The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java

The Politics of Inner Power: The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java By Ian Douglas Wilson Ph.D. Thesis School of Asian Studies Murdoch University Western Australia 2002 Declaration This is my own account of the research and contains as its main content, work which has not been submitted for a degree at any university Signed, Ian Douglas Wilson Abstract Pencak silat is a form of martial arts indigenous to the Malay derived ethnic groups that populate mainland and island Southeast Asia. Far from being merely a form of self- defense, pencak silat is a pedagogic method that seeks to embody particular cultural and social ideals within the body of the practitioner. The history, culture and practice of pencak in West Java is the subject of this study. As a form of traditional education, a performance art, a component of ritual and community celebrations, a practical form of self-defense, a path to spiritual enlightenment, and more recently as a national and international sport, pencak silat is in many respects unique. It is both an integrative and diverse cultural practice that articulates a holistic perspective on the world centering upon the importance of the body as a psychosomatic whole. Changing socio-cultural conditions in Indonesia have produced new forms of pencak silat. Increasing government intervention in pencak silat throughout the New Order period has led to the development of nationalized versions that seek to inculcate state-approved values within the body of the practitioner. Pencak silat groups have also been mobilized for the purpose of pursuing political aims. Some practitioners have responded by looking inwards, outlining a path to self-realization framed by the powers, flows and desires found within the body itself. -

Datar Isi Bab I

DATAR ISI BAB I : PENDAHULUAN ……………………………………………………………….. 23 BAB II : LATAR HISTORIS MTA DI . …. .. 24 BAB III : WAHABISME DAN GERAKAN PURIFIKASI DI PEDESAAN JAWA … …. 55 BAB IV : RESPONS ISLAM MAINSTREAM INDONESIA PADA MTA …….. 110 BAB V : KEBANGKITAN ISLAM POLITIK PADA PEMILU 2014 DI INDONESIA .. …160 BAB VI : PENUTUP …. …… 205 BAB I PENDAHULUAN Di awal abad ke-21, pasca runtuhnya Orde Baru, kesempatan politik semakin terbuka yang dimotori oleh gerakan reformasi Indonesia. Hal tersebut juga mendorong gerakan mobilisasi massa secara transparan dalam ruang publik. Hal ini menimbulkan munculnya berbagai macam gerakan sosial secara massif di Indonesia. Perubahan iklim politik pada Orde Reformasi tersebut, berpengaruh juga terhadap perkembangan kehidupan keagamaan masyarakat Islam di Indonesia. Pengaruh ini dapat dilihat dengan semakin menguatnya identitas dan gerakan kelompok keagamaan di luar mainstream kelompok keagamaan. Dalam perkembangan gerakan sosial keagamaan tersebut, terdapat tiga aspek yang menonjol, yaitu pertama, aspek yang didorong oleh orientasi politis, kedua orientasi keagamaan yang kuat, dan ketiga orientasi kebangkitan kultural rakyat Indonesia.1 Adapun dalam pendekatannya, kaum agamawan dan gerakan keagamaan, menurut AS Hikam, menggunakan dua pendekatan yaitu pendekatan “menegara” dan pendekatan “masyarakat”.2 Terdapat beberapa faktor yang secara bersamaan menggerakkan orang untuk membangun sebuah bangsa yang bersatu. Faktor-faktor tersebut tidak terbatas pada adanya kesamaan pengalaman masa lalu seperti ras, bahasa, dan -

Akuntansi Bantengan: Perlawanan Akuntansi Indonesia Melalui Metafora Bantengan Dan Topeng Malang

AKUNTANSI BANTENGAN: PERLAWANAN AKUNTANSI INDONESIA MELALUI METAFORA BANTENGAN DAN TOPENG MALANG Amelia Indah Kusdewanti1)* Achdiar Redy Setiawan2) Ari Kamayanti1) Aji Dedi Mulawarman1) 1)Universitas Brawijaya, Jl. MT. Haryono 165, Malang. 2)Universitas Trunojoyo Madura Surel: [email protected] Abstrak: Akuntansi Bantengan: Perlawanan Akuntansi Indonesia melalui Metafora Kesenian Bantengan dan Topengan Malang. Tujuan studi ini meng- usulkan bahwa melakukan perlawanan pada ‘kuasa’ yang sedang berperang merupakan usaha yang melelahkan. Bentuk perlawanan akan lebih bermakna bagi kepentingan rakyat apabila dilakukan oleh dan bagi rakyat. Pendekatan metafora digunakan untuk menelaah perang kuasa. Studi literatur mendalam serta wawancara dengan komunitas budaya, budayawan serta sejarawan meng- konfirmasi bahwa metafora Bantengan dan Topeng Malang tepat untuk meng- gambarkan kondisi ini. Artikel ini menunjukkan bahwa keberadaan Masyarakat Akuntansi Multiparadigma Indonesia (MAMI) adalah bentuk perlawanan Akun- tansi Bantengan yang menjadi motor penggerak pembangunan ilmu akuntansi menuju akuntansi Indonesia yang merdeka. Abstract: Bantengan Accounting: The Counterforce of Indonesian Account- ing through Bantengan and Topengan Malang Art as Methapor. This study proposes that the counterforce of this war should be done by the people and for them. The methapor is used to examine the war. In-depth study of literature and interviews with cultural communities, as well as cultural historians confirm that Bantengan and Topeng Malang appropriate to describe this condition. This arti- cle shows that the presence of Masyarakat Akuntansi Multiparadigma Indonesia (MAMI) as a form of Bantengan Accounting battle is a driving force toward the free- dom of Indonesian Accounting. Kata kunci: Bantengan, Topeng malang, MAMI, Metafora, Perang kuasa “Titenana yen mbesok wes ana sarpo kantaka Handoko Brang saka wetan dalane, sinuwuk ubrug wahana jati. -

The Once and Future King: Utopianism As Political Practice in Indonesia El Pasado Y Futuro Rey: Utopismo Como Práctica Política En Indonesia

12 The Once and Future King: Utopianism as Political Practice in Indonesia El pasado y futuro rey: utopismo como práctica política en Indonesia Thomas Anton Reuter Abstract A centuries-old practice persists on the island of Java, Indonesia, whereby utopian prophecies are used not only to critique the socio-political order of the day but also to outline an ideal form of government for the future. The prophecy text is attributed to a 12th century king, Jayabaya. This historical figure is celebrated as a ‘just king’ (ratu adil) and as an incarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, who is said to manifest periodically in human form to restore the world to order and prosperity. The prophecy predicts the present ‘time of madness’ (jaman edan) will culminate in a major crisis, followed by a restoration of cosmic harmony within a utopian society. Not unlike the work of Thomas More, and the genre of western utopian literature in general, the political concepts outlined in this Indonesian literary tradition have been a perennial source of inspiration for political change. Keywords: imagination, Indonesia, Java, prophecy, time, utopian literature. Resumen Una práctica centenaria persiste en la isla de Java, Indonesia, en la que profecías utópicas son usadas no solo para criticar el orden sociopolítico actual, sino también para trazar una forma ideal de un futuro gobierno. El texto profético es atribuido a Jayabaya, un rey del siglo XII. Esta figura histórica es reconocida como un rey justo (ratu adil) y como una encarnación del dios hindú Vishnu, quien se manifiesta periódicamente en forma humana para restaurar el orden mundial y la prosperidad. -

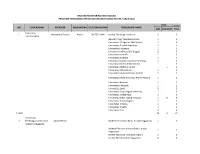

Ibm KKN-PPM 1 Universitas Tarumanagara Muhammad Zaman

WILAYAH MONITORING DAN EVALUASI PROGRAM PENGABDIAN KEPADA MASYARAKAT MONO TAHUN, TAHUN 2016 SKIM Grand WIL TUAN RUMAH REVIEWER PENDAMPING TELP PENDAMPING PERGURUAN TINGGI IbM KKN-PPM Total Universitas 1 Muhammad Zaman Anton 08170711344 Institut Teknologi Indonesia 3 3 Tarumanagara Sekolah Tinggi Teknologi Jakarta 1 1 Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta 1 1 Universitas Al-azhar Indonesia 2 2 Universitas Indonesia 1 1 Universitas Indonusa Esa Unggul 3 3 Universitas Islam 45 1 1 Universitas Jayabaya 1 1 Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya 1 1 Universitas Kristen Krida Wacana 1 1 Universitas Mathla ul Anwar 1 1 Universitas Mercu Buana 1 1 Universitas Muhammadiyah Jakarta 2 2 Universitas Muhammadiyah Prof Dr Hamka 1 1 Universitas Nasional 2 2 Universitas Pancasila 1 1 Universitas Sahid 2 2 Universitas Satya Negara Indonesia 1 1 Universitas Serang Raya 1 1 Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa 1 8 9 Universitas Tarumanagara 2 2 Universitas Terbuka 1 1 Universitas Trisakti 1 1 Universitas Yarsi 2 2 1 Total 33 9 42 Universitas 2 Pembangunan Nasional Ahmad Fahmi Akademi Kesehatan Karya Husada Yogyakarta 1 1 Veteran Yogyakarta Akademi Perawatan Karya Bakti Husada 1 1 Yogyakarta Institut Sains Dan Teknologi Akprind 5 5 Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta 6 6 SKIM Grand WIL TUAN RUMAH REVIEWER PENDAMPING TELP PENDAMPING PERGURUAN TINGGI IbM KKN-PPM Total Sekolah Tinggi Teknologi Nasional 2 2 Universitas Cokroaminoto 1 1 Universitas Muhammadiyah Magelang 5 5 Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran 11 11 Yogyakarta Universitas Teknologi Yogyakarta -

G. Drewes the Struggle Between Javanism and Islam As Illustrated by the Serat Dermagandul

G. Drewes The struggle between Javanism and Islam as illustrated by the Serat Dermagandul In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 122 (1966), no: 3, Leiden, 309-365 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 05:49:08AM via free access THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN JAVANISM AND ISLAM AS ILLUSTRATED BY THE SËRAT DERMAGANDUL \ JK I riting on the encyclopaedic character of the Sërat Ca- y y bolan and the Sërat Cëntini1 Dr Th. Pigeaud has classified the 'well-known Sërat Dërmagandul' as belonging to the same category of literary works, since in its elaborate redactions it showed a similar tendency towards expatiation on favourite subjects of Javanese lore. Moreover, in the struggle between the inherited religious concepts and Muslim orthodoxy it sided with those who clung to the time-honoured Javanese speculations on man and his place in the universe as against the legalist view of Islam, just as the Cëntini books did. Should, however, the epithet 'well-known' have prompted an in- quisitive reader to investigate the existing literature in search of further information on the Sërat Dërmagandul, then he would not have been long in finding that, for instance, neither in the Leiden catalogues of Javanese MSS. nor in the abstracts of Javanese printed books in the library of the (former) Batavia Society at Jakarta is a work of this name mentioned, let alone described.2 Nor was a Sërat Dërmagandul recorded by Dr Poerbatjaraka in his Alphabetical List of Javanese MSS. in the library of the (former) Batavia Society.3 Even if he continued his research by Consulting what was published after 1933, he would not find a summary of the work in question until 1939.