Religion, Imperialism, and Resistance in Nineteenth Century's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Indonesia: the Unlikely Nation?

History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page i A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Series Editor: Milton Osborne Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of eight books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979 and now in its eighth edition, and, most recently, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, published in 2000. History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA THE UNLIKELY NATION? Colin Brown History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iv First published in 2003 Copyright © Colin Brown 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Brown, Colin, A short history of Indonesia : the unlikely nation? Bibliography. -

J. Noorduyn Bujangga Maniks Journeys Through Java; Topographical Data from an Old Sundanese Source

J. Noorduyn Bujangga Maniks journeys through Java; topographical data from an old Sundanese source In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 138 (1982), no: 4, Leiden, 413-442 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 01:16:49AM via free access J. NOORDUYN BUJANGGA MANIK'S JOURNEYS THROUGH JAVA: TOPOGRAPHICAL DATA FROM AN OLD SUNDANESE SOURCE One of the precious remnants of Old Sundanese literature is the story of Bujangga Manik as it is told in octosyllabic lines — the metrical form of Old Sundanese narrative poetry — in a palm-leaf MS kept in the Bodleian Library in Oxford since 1627 or 1629 (MS Jav. b. 3 (R), cf. Noorduyn 1968:460, Ricklefs/Voorhoeve 1977:181). The hero of the story is a Hindu-Sundanese hermit, who, though a prince (tohaari) at the court of Pakuan (which was located near present-day Bogor in western Java), preferred to live the life of a man of religion. As a hermit he made two journeys from Pakuan to central and eastern Java and back, the second including a visit to Bali, and after his return lived in various places in the Sundanese area until the end of his life. A considerable part of the text is devoted to a detailed description of the first and the last stretch of the first journey, i.e. from Pakuan to Brëbës and from Kalapa (now: Jakarta) to Pakuan (about 125 lines out of the total of 1641 lines of the incomplete MS), and to the whole of the second journey (about 550 lines). -

Land- En Volkenkunde

Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal- , Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (The University of Sydney) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) volume 313 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ vki Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Singing is a Medicine By Wim van Zanten LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY- NC- ND 4.0 license, which permits any non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by- nc- nd/ 4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Front: angklung players in Kadujangkung, Kanékés village, 15 October 1992. Back: players of gongs and xylophone in keromong ensemble at circumcision festivities in Cicakal Leuwi Buleud, Kanékés, 5 July 2016. Translations from Indonesian, Sundanese, Dutch, French and German were made by the author, unless stated otherwise. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020045251 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

The Once and Future King: Utopianism As Political Practice in Indonesia El Pasado Y Futuro Rey: Utopismo Como Práctica Política En Indonesia

12 The Once and Future King: Utopianism as Political Practice in Indonesia El pasado y futuro rey: utopismo como práctica política en Indonesia Thomas Anton Reuter Abstract A centuries-old practice persists on the island of Java, Indonesia, whereby utopian prophecies are used not only to critique the socio-political order of the day but also to outline an ideal form of government for the future. The prophecy text is attributed to a 12th century king, Jayabaya. This historical figure is celebrated as a ‘just king’ (ratu adil) and as an incarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, who is said to manifest periodically in human form to restore the world to order and prosperity. The prophecy predicts the present ‘time of madness’ (jaman edan) will culminate in a major crisis, followed by a restoration of cosmic harmony within a utopian society. Not unlike the work of Thomas More, and the genre of western utopian literature in general, the political concepts outlined in this Indonesian literary tradition have been a perennial source of inspiration for political change. Keywords: imagination, Indonesia, Java, prophecy, time, utopian literature. Resumen Una práctica centenaria persiste en la isla de Java, Indonesia, en la que profecías utópicas son usadas no solo para criticar el orden sociopolítico actual, sino también para trazar una forma ideal de un futuro gobierno. El texto profético es atribuido a Jayabaya, un rey del siglo XII. Esta figura histórica es reconocida como un rey justo (ratu adil) y como una encarnación del dios hindú Vishnu, quien se manifiesta periódicamente en forma humana para restaurar el orden mundial y la prosperidad. -

Ibm KKN-PPM 1 Universitas Tarumanagara Muhammad Zaman

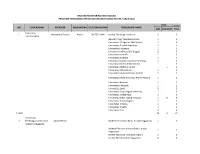

WILAYAH MONITORING DAN EVALUASI PROGRAM PENGABDIAN KEPADA MASYARAKAT MONO TAHUN, TAHUN 2016 SKIM Grand WIL TUAN RUMAH REVIEWER PENDAMPING TELP PENDAMPING PERGURUAN TINGGI IbM KKN-PPM Total Universitas 1 Muhammad Zaman Anton 08170711344 Institut Teknologi Indonesia 3 3 Tarumanagara Sekolah Tinggi Teknologi Jakarta 1 1 Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta 1 1 Universitas Al-azhar Indonesia 2 2 Universitas Indonesia 1 1 Universitas Indonusa Esa Unggul 3 3 Universitas Islam 45 1 1 Universitas Jayabaya 1 1 Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya 1 1 Universitas Kristen Krida Wacana 1 1 Universitas Mathla ul Anwar 1 1 Universitas Mercu Buana 1 1 Universitas Muhammadiyah Jakarta 2 2 Universitas Muhammadiyah Prof Dr Hamka 1 1 Universitas Nasional 2 2 Universitas Pancasila 1 1 Universitas Sahid 2 2 Universitas Satya Negara Indonesia 1 1 Universitas Serang Raya 1 1 Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa 1 8 9 Universitas Tarumanagara 2 2 Universitas Terbuka 1 1 Universitas Trisakti 1 1 Universitas Yarsi 2 2 1 Total 33 9 42 Universitas 2 Pembangunan Nasional Ahmad Fahmi Akademi Kesehatan Karya Husada Yogyakarta 1 1 Veteran Yogyakarta Akademi Perawatan Karya Bakti Husada 1 1 Yogyakarta Institut Sains Dan Teknologi Akprind 5 5 Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta 6 6 SKIM Grand WIL TUAN RUMAH REVIEWER PENDAMPING TELP PENDAMPING PERGURUAN TINGGI IbM KKN-PPM Total Sekolah Tinggi Teknologi Nasional 2 2 Universitas Cokroaminoto 1 1 Universitas Muhammadiyah Magelang 5 5 Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran 11 11 Yogyakarta Universitas Teknologi Yogyakarta -

The Once and Future King: Utopianism As Political Practice in Indonesia El Pasado Y Futuro Rey: Utopismo Como Práctica Política En Indonesia

12 The Once and Future King: Utopianism as Political Practice in Indonesia El pasado y futuro rey: utopismo como práctica política en Indonesia Thomas Anton Reuter Abstract A centuries-old practice persists on the island of Java, Indonesia, whereby utopian prophecies are used not only to critique the socio-political order of the day but also to outline an ideal form of government for the future. The prophecy text is attributed to a 12th century king, Jayabaya. This historical figure is celebrated as a ‘just king’ (ratu adil) and as an incarnation of the Hindu God Vishnu, who is said to manifest periodically in human form to restore the world to order and prosperity. The prophecy predicts the present ‘time of madness’ (jaman edan) will culminate in a major crisis, followed by a restoration of cosmic harmony within a utopian society. Not unlike the work of Thomas More, and the genre of western utopian literature in general, the political concepts outlined in this Indonesian literary tradition have been a perennial source of inspiration for political change. Keywords: imagination, Indonesia, Java, prophecy, time, utopian literature. Resumen Una práctica centenaria persiste en la isla de Java, Indonesia, en la que profecías utópicas son usadas no solo para criticar el orden sociopolítico actual, sino también para trazar una forma ideal de un futuro gobierno. El texto profético es atribuido a Jayabaya, un rey del siglo XII. Esta figura histórica es reconocida como un rey justo (ratu adil) y como una encarnación del dios hindú Vishnu, quien se manifiesta periódicamente en forma humana para restaurar el orden mundial y la prosperidad. -

G. Drewes the Struggle Between Javanism and Islam As Illustrated by the Serat Dermagandul

G. Drewes The struggle between Javanism and Islam as illustrated by the Serat Dermagandul In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 122 (1966), no: 3, Leiden, 309-365 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 05:49:08AM via free access THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN JAVANISM AND ISLAM AS ILLUSTRATED BY THE SËRAT DERMAGANDUL \ JK I riting on the encyclopaedic character of the Sërat Ca- y y bolan and the Sërat Cëntini1 Dr Th. Pigeaud has classified the 'well-known Sërat Dërmagandul' as belonging to the same category of literary works, since in its elaborate redactions it showed a similar tendency towards expatiation on favourite subjects of Javanese lore. Moreover, in the struggle between the inherited religious concepts and Muslim orthodoxy it sided with those who clung to the time-honoured Javanese speculations on man and his place in the universe as against the legalist view of Islam, just as the Cëntini books did. Should, however, the epithet 'well-known' have prompted an in- quisitive reader to investigate the existing literature in search of further information on the Sërat Dërmagandul, then he would not have been long in finding that, for instance, neither in the Leiden catalogues of Javanese MSS. nor in the abstracts of Javanese printed books in the library of the (former) Batavia Society at Jakarta is a work of this name mentioned, let alone described.2 Nor was a Sërat Dërmagandul recorded by Dr Poerbatjaraka in his Alphabetical List of Javanese MSS. in the library of the (former) Batavia Society.3 Even if he continued his research by Consulting what was published after 1933, he would not find a summary of the work in question until 1939. -

Indonesia – Bali – Nurdin Mohammed Top – State Protection – Internal Relocation

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IDN30273 Country: Indonesia Date: 6 July 2006 Keywords: IDN30273 – Indonesia – Bali – Nurdin Mohammed Top – State protection – Internal relocation This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Please provide information about Nurdin’s group. Is it limited to Bali? 2. Please provide information as to whether the authorities protect the citizens of Bali/Indonesia. 3. Are there regions other than Bali within Indonesia to which a Hindu could relocate? 4. Any other relevant information. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information about Nurdin’s group. Is it limited to Bali? Networks associated with Noordin Mohammed Top are widely considered to be responsible for the October 2002 Bali suicide/car bomb attacks, the August 2003 bombing of the Marriott Hotel in Jakarta, the September 2004 bombing of the Australian Embassy in Jakarta, and the October 2005 triple suicide bomb attacks in Bali. An extensive report on Noordin’s networks was recently completed by the International Crisis Group (ICG) and, according to this report, the persons involved in Noordin’s activities have, for the most part, been based in Java (p.16) (the vicinity of Solo, in Central Java, has been of particular importance). The report also makes mention of Noordin affiliates operating out of numerous localities across Indonesia, including, for example, Surabaya, Semarang, Ungaran, Pasaruan, Pekalongan and Bangil, in Java; Bukittinggi, Bengkulu, Lampung and Riau, in Sumatra; and in the areas of Sulawesi, Poso and Ambon (and also, beyond Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia). -

Review of Termination of Post-Reformation President in Indonesia’S State Systems

Review of Termination of Post-Reformation President In Indonesia’s State Systems Setiyanto1 {[email protected]} [email protected] 1Law Doctoral Graduate Program Students Jayabaya University Jakarta, Indonesia Abstract. One aspect of the study in state administration law that is crucial is filling and dismissal of the position of President. This can be understood given the position of President in Indonesia not only as a representation of the head of government but at the same time the head of state. Before reforms, the state administrative law approach in dismissing the president tends to be approached from political aspects. As the President can be dismissed by the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) through a Special Session if it violates the direction of the state. This provision is not stated on the torso but in the Explanation of the 1945 Constitution. Benchmarks violate the bow the country is very difficult to determine legally. Keywords: Termination, Post-Reformation, Indonesia’s State Systems 1 Introduction The reformation of Indonesia in 1998 has implications for changing the institutionalization of democracy. This is the implication after so long the authoritarian regime of the New Order confined freedom (freedom) as the heart of freedom. Democracy itself is indeed a term that is not simple and sometimes has complications here and there. However, the strength of democracy, it can still correct the system it builds on the basis of authentic public aspirations. The institutionalization of democracy also afflicts the position of President. The President is a strategic position in the form of a republican government which has a very important role in managing the country. -

Contribution to Local Wisdom Leadership of the National Policy on Java (Descriptive Study Against Election and Designation of President of the Republic of Indonesia)

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 5, ISSUE 06, JUNE 2016 ISSN 2277-8616 Contribution To Local Wisdom Leadership Of The National Policy On Java (Descriptive Study Against Election And Designation Of President Of The Republic Of Indonesia) M. Husein Maruapey Abstract: Experts in political science and the state of national leadership position as an important factor that is often discussed in all good perspective perspective on local wisdom and teachings of Islam. If researched and studied carefully, the teaching guidelines for indigenous people live or Java with the teachings of the Qur'an and the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad., analysis, that the philosophy of the Javanese, the teachings of the Qur'an, and the Sunnah of Rasul has vertical and horizontal relationships inseparable and indisputable that both synergistic. Both of these components affect public policy in the election of the national leadership until now. The ancestral philosophy applies continues throughout life. Javanese cultural heritage of thinking is even able to broaden one's wisdom. Leadership is one of the urgent problems which disappeared from our people today. Crises in various fields that happen to us due to the absence of clear national goals as our orientation, that is the goal we want to accomplish together that should unite our plans and provide rationality and harmony. Formation of leadership is the problem of the people. Index Terms: Public Policy, Local Wisdom Java, National Leadership ———————————————————— 1 Introduction "Matters regarding the transfer of power and others organized The West since time immemorial has been bequeathed way carefully", that the statement contains a political meaning, teachings to the construction of high moral character, so anyone children of this nation have the same rights as participate in building the civilization of this nation full of others to lead the nation this in order to realize the ideals of morality. -

KERAJAAN ALLAH DALAM DUA WAJAH Datangnya Ratu Adil Dan Kerajaan Allah

Vol. 03, No. 02, November 2014, hlm. 99-109 KERAJAAN ALLAH DALAM DUA WAJAH Datangnya Ratu Adil dan Kerajaan Allah Stepanus Istata Raharjo ABSTRACT: The javanese mysticism (Kejawen) reflects a kind of messianic idea of a just king (Ratu Adil) that can be compared to the notion of "God's reign" in Christianity. The concept of "Ratu Adil" had inevitably influenced javanese customs, language system as well as various ritual traditions. Considering that the Kejawen itself is a mixture of various elements from different religious systems (such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam), it is neccessary to trace back sources or traditions, from which the notion of Ratu Adil had been developed. This article aims to discuss and to compare the understanding of "Ratu Adil" with the notion of "God's reign". Kata-Kata Kunci: Kerajaan Allah, Ratu Adil, kejawen, tradisi Kristiani. 1. PENGANTAR penalaran artikel ini disusun sebagai berikut. Pertama-tama akan dipaparkan konsep “kejawen” Kerajaan Allah telah hadir di tengah-tengah yang menjadi latar belakang bagi konsep “Ratu kita, tetapi kepenuhannya masih dinantikan. Ia Adil” yang dipahami oleh tradisi Jawa. Selan- sudah dan sekaligus belum. Ia hadir dalam diri jutnya menyusul konsep Kerajaan Allah dalam Yesus dengan pewartaan dan karya-karya-Nya tradisi Kristiani (Kitab Suci). Pada bagian akhir namun kepenuhannya tetap dinantikan hari dan ditampilkan analisis kritis terhadap konsep “Ratu saatnya. Itulah sebabnya Kerajaan Allah boleh Adil” dan “Kerajaan Allah”. Dengan kata lain, disebut tampil dalam “dua wajah”. Wajah yang artikel ini ditulis dengan menggunakan metode pertama hadir dalam diri Yesus, ketika Ia analisis kritis. berkata: “Waktunya telah genap; Kerajaan Allah sudah dekat. -

G. Resink from the Old Mahabharata - to the New Ramayana-Order

G. Resink From the old Mahabharata - to the new Ramayana-order In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 131 (1975), no: 2/3, Leiden, 214-235 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 04:17:30AM via free access G. J. RESINK FROM THE OLD MAHABHARATA- TO THE NEW RAMAYANA-ORDER* ". the Bharata Judha can be performed again — when Java will again be free . ." Pronouncement of a nineteenth century dalang. Some people not only live, but also die and kill by myths. So the well-known Darul Islam leader S. M. Kartosoewirjo wrote in a secret note to President Soekarno in 1951, prophesying entirely from the myth of a Javanese version of the Mahabharata epic, that a "Perang Brata Juda Djaja Binangun" was imminent. This conflict would lead to a confrontation with Communism — to which the expression "Lautan Merah" alluded —- and world revolution.1 The Javanese santri who was to advocate and lead the jihad or holy war in defence of an Islamic Indonesian state was writing to the Javanese abangan here in terms which both understood perfectly well. For it was precisely this wayang story that was usually staged as a bersih desa rite or a ngruwat ceremony for purposes of "purification" or the exorcism of all evil and misfortune that had ever struck or threatened still to befall the community. As a student I once witnessed such a performance together with my mother in the village of Karang Asem, to the north of Yogya. She wrote about it in the journal Djdwd, referring in particular to how the women fled the scène towards mid- * I feel most indebted to Dr.