Trafficking in Transnistria: the Role of Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 SUCEAVA COUNTY COUNCIL Department of External Partnerships

SUCEAVA COUNTY COUNCIL Department of external partnerships and diaspora Chernivtsi region The most important activities commonly developed, since the signing of the partnership between Suceava county and Chernivtsi region, in Ukraine, were as follows: - twinning between schools and territorial-administrative units from Suceava county with similar ones from Chernivtsi region; - exchanges of experience between specialists from different fields of activity in the two regions; - participation, based on reciprocity, in rest camps, organized for children; - organizing, in common, folklore festivals, poetry contests, performances; - study trips; - sport competitions between students; - organizing conferences, symposiums, training activities with the participation of teachers, school inspectors and school directors from the two partner regions in order to conclude partnerships and to promote projects of common interest; - exchange of teaching materials, books; - providing school programs for the assimilation (familiarization with) of the mother tongue, knowledge of the history and traditions of minorities; - regular work meetings at the headquarters of the two administrative-territorial units, as well as at the PCTF Siret-Porubne and Porubne-Siret, with the participation of the administrative leaders of Suceava county and Chernivtsi region. In the field of culture, a series of activities of particular importance have been carried out, for the organization of which Suceava County Council, as well as the Cernăuţi Regional State Administration and -

Academia De Ştiinţe a Moldovei Institutul Patrimoniului Cultural

E-ISSN 2537–6152 Categoria B ACADEMIA DE ŞTIINŢE A MOLDOVEI INSTITUTUL PATRIMONIULUI CULTURAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF MOLDOVA THE INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК МОЛДОВЫ ИНСТИТУТ КУЛЬТУРНОГО НАСЛЕДИЯ REVISTA DE ETNOLOGIE ŞI CULTUROLOGIE Volumul XX THE JOURNAL OF ETHNOLOGY AND CULTUROLOGY Volume XX ЖУРНАЛ ЭТНОЛОГИИ И КУЛЬТУРОЛОГИИ Том XX CHIŞINĂU, 2016 Colegiul de redacție: Procop S. Redactor principal. Doctor în filologie, Duşacova N. Doctor în istorie, cercetător ştiinţific conferenţiar, director al Centrului de Etnologie al Insti- superior, Centrul de Tipologie şi Semiotică a Folclorului, tutului Patrimoniului Cultural al AȘM. svetlanaprocop@ Universitatea de Stat din Rusia (Moscova). dushakova@ mail.ru list.ru Zaicovschi T. Redactor responsabil. Doctor în filolo- Ghinoiu I. Doctor în geografie, cercetător ştiinţific gie, conferenţiar, cercetător ştiinţific coordonator la Cen- principal, gradul I, secretar ştiinţific al Institutului de trul de Etnologie al Institutului Patrimoniului Cultural. Etnografie şi Folclor „C. Brăiloiu”, Academia Română [email protected] (Bucureşti). [email protected] Damian V. Secretar responsabil. Doctor în istorie, Guboglo M. Doctor habilitat în istorie, profesor, cercetător ştiinţific superior la Centrul de Etnologie al vice-director al Institutului de Etnologie şi Antropolo- IPC al AȘM. [email protected] gie „N. Mikluho-Maklai”, Academia de Știinţe din Rusia Cara N. Doctor în filologie, cercetător ştiinţific co- (Moscova). [email protected] ordonator la Centrul de Etnologie al Institutului Patrimo- Nicoglo D. Doctor în istorie, cercetător ştiinţific niului Cultural al AȘM. [email protected] superior la Centrul de Etnologie al IPC al AȘM. Derlicki J. Doctor în etnologie, cercetător ştiinţific [email protected] la Departamentul de Etnologie al Institutului de Arhe- S te p a n o v V. -

Workshop on Natura 2000 Management

Workshop on Natura 2000 Management Threats, Challenges and Solutions With a specific focus on management of forest and grassland habitats in the Alpine biogeographic region The state of play of Natura 2000 management and financing in Romania prepared by Laura Done, Speleological Foundation "Club Speo Bucovina" Please answer the following questions regarding recent developments of Natura 2000 in your country. 1. Last development of the establishment of Natura 2000: • are there any changes in the Natura 2000 coverage in the last years: Yes, geographical diversification and competence domains. • do you expect any changes in the next few years: Yes, we expect that more areas to be added to Natura2000 network. • do you consider that the network is complete: No. There are still many studies to be made and approved for areas that need to be included in the network. • Any ideas for CEEweb support and activities in this field? Facilitating the exchange of good practices between the NGOs in the network. Involving the young people in Natura 2000 projects. 2. SAC designation process: • how many SCI till now: SCIs on Suceava County territory approved through the order of the Ministry of Environment and Forests No.2387/2011 to modify the order of the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development No.1964/2007 regarding naming natural protected areas of comuniotary importance as integrated part of the ecological European network Natura 2000: 1. ROSCI0010 – Bistrița Aurie (Golden Bistrita) – situated on the administrative territories of Cârlibaba, Ciocăneşti and Iacobeni, administred by Romanian Waters; ‐ plans started to be developed 2. ROSCI0019 – Călimani – Gurghiu ‐ situated on the administrative territories of Poiana Stampei, Dorna Candrenilor, Panaci and Şaru Dornei, administred by Călimani National Park; ‐ plans are ready 4. -

“Romanian Waters”, Head of River Basin Management Plans Office, Bucharest, Romania

NATIONAL ADMNISTRATION “ROMANIAN WATERS” Romania key input to the Second Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Groundwaters under the UNECE Water Convention Prut River Basin CORINA COSMINA BOSCORNEA, PhD National Administration “Romanian Waters ”, Head of River Basin Management Plans Office, Bucharest, Romania Ukraine - Kiev, 28 th April 2010 Second Assessment of Transboundary Rivers, Lakes and Romanian transboundary river basins Information about transboundary river basins: •Somes/Szamos, •Mures/Maros, •Crisuri, Tisza River •Banat, basin •Siret, •Prut, •Dobrogea-Litoral , •Arges-Vedea Danube •Banat River Basin •Buzau-Ialomita District •Jiu Romanian river basins Prut river basins in the Danube river basin district Prut river basin 1. General description of the Prut river basin The total Population Area in area of the Major density in the Shared the Character with an river basin transbound area in the countries country in average elevation in the ary river country km² (%) country (persons/km 2) upland character Romania, (Ukrainian 10,990 Ukraine and 27820 Prut Carpathians) and 55 (39.5%) Moldova lowland (lower reaches) • The Prut river basin is shared by Ukraine, Romania and Moldova Its source is in the Ukrainian Carpathians. Later, the Prut forms the border between Romania and Moldova. • The rivers Lapatnic, Drageste and Racovet are transboundary tributaries in the Prut sub-basin; they cross the Ukrainian- Moldavian border. • The Prut River’s major national tributaries are the rivers Cheremosh and Derelui, (Ukraine), Baseu, Jijia, -

Moldova, Moldavia, Bessarabia Yefim Kogan, 25 September 2015

Moldova, Moldavia, Bessarabia Yefim Kogan, 25 September 2015 Dear Researchers, I have received recently an email from Marilyn Newman: Hello Yefim, I've been following this project and appreciate your more complete break down in today's Jewishgen Digest. I did contribute to Bob Wascou before he passed. The reason for this message is that I'm confused. My family were from Moinesti and Tirgu Ocna, both near each other in Moldova. However, this area was not Bessarabia..... Can you explain what areas of Moldova are covered other than Bessarabia and Chisanou (sp.). Many Thanks, Marilyn Newman Marilyn thank you. I think this is a very important question. I was getting many similar message for many years. Let’s clear this confusion. Let's start with terminology. The term Moldavia and Moldova mean the same region! Moldova is in Romanian language and Moldavia was adopted by Russian and other languages, including English. Charles King in 'The Moldovans. Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture', Stanford U., 1999 writes that 'It is a myth that Moldova changed its name from Moldavia. What happened in the 1990s was simply that we in the West became better informed about what locals themselves had always called it.' So let's dive into the history of the region: Moldavia is known as a country or Principality from 14 century until 1812. There were also two other Danube or Romanian Principalities - Walachia and Transilvania. At some point in the history Moldavia joined other Principalities. In 1538 Moldavia surrendered to Ottoman Empire, and remained under Turks for about 300 years. -

Bout, Viktor Et Al. S1 Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 17, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL, JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA PAUL KNIERIM OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-8244 U.S. ANNOUNCES NEW INDICTMENT AGAINST INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER VIKTOR BOUT AND AMERICAN CO-CONSPIRATOR FOR MONEY LAUNDERING, WIRE FRAUD, AND CONSPIRACY PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," and his associate RICHARD AMMAR CHICHAKLI, a/k/a "Robert Cunning," a/k/a "Raman Cedorov," for allegedly conspiring to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA") stemming from their efforts to purchase two aircraft from companies located in the United States, in violation of economic sanctions which prohibited such financial transactions. The Indictment unsealed today also charges BOUT and CHICHAKLI with money laundering conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and six separate counts of wire fraud, in connection with these financial transactions. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. Since BOUT's arrest, the United States has been actively pursuing his extradition from Thailand on a separate set of U.S. charges. Those charges allege that BOUT conspired to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. -

The Role of Germany in the Transnistria Conflict

Przegląd Strategiczny 2020, Issue 13 Bogdan KOSZEL DOI : 10.14746/ps.2020.1.7 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7118-3057 THE ROLE OF GERMANY IN THE TRANSNISTRIA CONFLICT HISTORIC BACKGROUND The territory of Transnistria is a special enclave on the left bank of the Dniester River, with cultural and historical traditions markedly different than those in neighbor- ing Moldova. The Ottoman conquests, followed by the partitioning of Poland, made the Dniester a river marking the border between the Russian and Turkish empires. When Turkey grew weaker in the international arena and Russia grew stronger after its victory over Napoleon, the territory – known as Bessarabia – fell under Russian rule until 1918, to be embraced by Greater Romania after the collapse of tsarism (Lubicz- Miszewski, 2012: 121–122). After the Soviet Union was formally established in 1922, the Moscow government immediately began to question the legality of Bessarabia’s inclusion within Romania and never accepted this annexation. In 1924, the Moldovan Autonomous Socialist So- viet Republic (MASSR) was established on the left bank of the Dniester as an integral part of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic. Before World War II, Germany showed no interest in this region of Europe, believ- ing that this territory was a zone of influence of its ally, the Austro-Hungarian mon- archy, and then of the Soviet Union. In the interwar period, Romania was a member of the French system of eastern alliances (Little Entente) and Berlin, which supported Hungarian revisionist sentiments, held no esteem for Bucharest whatsoever. At the time of the Weimar Republic, Romania became interested in German capital and ob- taining a loan from the Wolff concern to develop their railroads, but Germany shunned any binding declarations (Koszel, 1987: 64). -

Putin's Frozen Conflicts and the Conflict in Ukraine

Antagonizing the Neighborhood: Putin’s Frozen Conflicts and the Conflict in Ukraine Testimony before Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment Committee on Foreign Relations United States House of Representatives March 11, 2020 Stephen B. Nix, Esq. Eurasia Regional Director International Republican Institute A nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing democracy worldwide Stephen B. Nix, Esq. Congressional Testimony House Committee on Foreign Affairs March 11, 2020 Chairman Keating, Ranking Member Kinzinger, Members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today. The conflicts imposed upon Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova by Vladimir Putin have created military, political and policy challenges in all these countries. In addition to providing factual and political analysis in all the countries, we hope to provide the subcommittee with policy recommendations as to how the U.S. might engage in all these situations. Ukraine – Crimea and Donbas Since assuming office, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has dramatically enhanced his government’s efforts to resolve the crisis posed by the Russian-occupied territories of Donbas and Crimea. In a few short months, the Ukrainian government has increased its level of engagement with Ukrainian citizens still residing in these territories, improved the quality of critical public services to address needs created by the conflict, and re-invigorated diplomatic efforts to increase international pressure on the Kremlin to allow for the reintegration of these territories. It is crucial that the United States does all it can to support the Ukrainian government in achieving these aims. Challenges The conflict has created a humanitarian crisis in Donbas as vital public infrastructure, such as airports, bridges, highways, apartment buildings, and power and water lines have been destroyed or severely damaged. -

Progress Report for 2009

Contract number: 2009/219-955 Project Title: Building confidence between Chisinau and Tiraspol Report starting date: 01 January 2010 Report end date: 31 December 2011 Implementing agency: UNDP Moldova Country: Republic of Moldova Support to Confidence Building Measures II – Final Report 2010-2011 – submitted by UNDP Moldova 1 Table of Contents I. SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 III. PROJECT BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................. 5 1. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2. COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................................................................ 6 3. CIVIL SOCIETY DEVELOPMENT ...................................................................................................................................... 7 4. SUPPORT TO CREATION OF DNIESTER EUROREGION AND RESTORATION OF RAILWAY TRAFFIC. ........................................... 7 IV. SUMMARY OF IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS ......................................................................................... -

Research Paper Research Division – NATO Defense College, Rome – No

Research Paper Research Division – NATO Defense College, Rome – No. 122 – December 2015 The Transnistrian Conflict in the Context of the Ukrainian Crisis by Inessa Baban1 Until recently, relatively little was known about the Transnistrian conflict that has been undermining the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the Republic of Moldova since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The The Research Division (RD) of the NATO De- fense College provides NATO’s senior leaders with waves of enlargement towards the East of NATO and the European sound and timely analyses and recommendations on current issues of particular concern for the Al- Union drew attention to Transnistria, which has been seen as one of the liance. Papers produced by the Research Division convey NATO’s positions to the wider audience “frozen conflict zones” in the post-Soviet area alongside Abkhazia, South of the international strategic community and con- tribute to strengthening the Transatlantic Link. Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh. However, the Transnistrian issue has The RD’s civil and military researchers come from not been perceived as a serious threat to Euro-Atlantic security because a variety of disciplines and interests covering a broad spectrum of security-related issues. They no outbreaks of large-scale hostilities or human casualties have been conduct research on topics which are of interest to the political and military decision-making bodies reported in the region since the 1990s. Beyond a few small incidents in of the Alliance and its member states. the demilitarized zone, the 1992 ceasefire has been respected for more The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the than two decades. -

Introduction 2 Setting up a State

Notes Introduction 1. Clement Dodd (1993) edited a volume on Turkish Cypriot affairs, cover- ing political, social, and economic areas. More recent research has been concerned with particular issues such as the dynamics of political econ- omy (Lacher and Kaymak, 2005; Sonan, 2007); the question of Turkish Cypriot identity building and social conflicts within Northern Cyprus (Kızılyürek and Gautier-Kızılyürek, 2004; Hatay, 2005, 2008; Ramm, 2006; Navaro-Yashin, 2006); as well as the analysis of the connection of Turkish Cypriot sovereignty with Turkey’s involvement from different perspec- tives (Navaro-Yashin, 2003; Bahcheli, 2004a). The case of Transdniestria, on the other hand, has been marked by a paucity of research. Whereas economic developments have been followed in detail by Moldova’s Center for Strategic Studies and Reforms (CISR), internal political dynamics have been explored in only a very few specialized articles (Büscher, 1996; Tröbst, 2003; Hanne, 2004; Korobov and Byanov, 2006; Protsyk, 2009). 2 Setting up a State 1. The metaphor is borrowed from Richmond (2002a) mentioned in Chapter 1. 2. Although it is widely believed that Denktas¸ was the founder and leader of the TMT, Denktas¸ himself described his role within the organization as a political advisor (Cavit, 1999, p. 512). For an alternative view of the TMT’s activities and Turkey’s role in the formation of this group see Ionnides (1991). 3. It should be noted, however, that although these armed clashes are often referred to as ‘inter-communal’ fighting, on closer examination this term is a misnomer. The two armed groups were highly nationalist in ideology. -

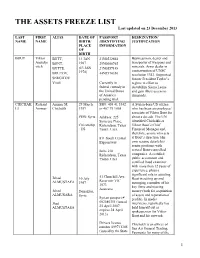

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last Updated on 23 December 2013

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last updated on 23 December 2013 LAST FIRST ALIAS DATE OF PASSPORT DESIGNATION/ NAME NAME BIRTH/ /IDENTIFYING JUSTIFICATION PLACE INFORMATION OF BIRTH BOUT Viktor BUTT, 13 JAN 21N0532664 Businessman, dealer and Anatolje BONT, 1967 29N0006765 transporter of weapons and vitch minerals. Arms dealer in BUTTE, (13 JAN 21N0557148 1970) contravention of UNSC BOUTOV, 44N3570350 resolution 1343. Supported SERGITOV former President Taylor’s Vitali Currently in regime in effort to federal custody in destabilize Sierra Leone the United States and gain illicit access to of America diamonds. pending trial. CHICHAK Richard Ammar M. 29 March SSN: 405 41 5342 A Syrian-born US citizen LI Ammar Chichakli 1959 or 467 79 1065 who has been an employee/ associate of Viktor Bout for POB: Syria Address: 225 about a decade. The UN Syracuse Place, identified Chichakli as Citizenship Richardson, Texas Viktor Bout’s Chief : US 75081, USA Financial Manager and, therefore, as one who acts 811 South Central at Bout’s direction. His Expressway own resume details his senior positions with several Bout-controlled Suite 210 Richardson, Texas companies. A certified 75080, USA public accountant and certified fraud examiner with more than 12 years of experience, plays a significant role in assisting 51 Churchill Ave. Jehad 10 July Bout in setting up and Reservoir VIC ALMUSTAFA 1967 managing a number of his 3073 key firms and moving Australia Jehad Deirazzor, money (both for acquisition ALMUSARA Syria of assets and reparation of Syrian passport # profits). In media Jhad 002680351 (issued interviews, reportedly has ALMUSTASA 25 April 2007, held himself out as expires 24 April spokesperson for Viktor 2013) Bout and his network.