UN Targeted Sanctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Save the Arms Embargo Peter Wallensteen 100 Hesburgh Center P.O

policy brief No. 14, January 2008 Save the Arms Embargo Peter Wallensteen 100 Hesburgh Center P.O. Box 639 One of the first measures contemplated by the United Nations when confronting a new University of Notre Dame security crisis is to institute an arms embargo. Since the end of the Cold War – which Notre Dame, IN 46556-0639 liberated international action from the constraints of major power confrontation – there have been 27 such embargoes. In addition to these UN embargoes, there are also Phone: (574) 631-6970 unilateral measures: The United States imposes its own arms sanctions on some Fax: (574) 631-6973 countries (including Cuba), as does the European Union, sometimes directed at the E-mail: [email protected] same targets, notably Burma/Myanmar and Zimbabwe. Are they used at the right Web: http://kroc.nd.edu moment, and do they have the effects the UN would want? The list of failures is, indeed, long. The most striking is the arms embargo on Somalia, which has been in place since 1992 without any settlement in sight. Is it time to forget about this meas- ure? Or is it time to save the embargo? If it is time to save the embargo, as this brief contends, what lessons can be drawn about the optimal use of embargoes, and under what conditions can they work? Gerard F. Powers The appeal of the arms embargo to the sender is obvious: It means that “we, the Director of Policy Studies initiators,” are not supplying means of warfare and repression to regimes we think should not have them. -

Security Council Press Statement on the Central African Republic

Code: SC/PR 1/1 Committee: Security Council Topic: The crisis in the Central African Republic Security Council Press Statement on the Central African Republic The members of the Security Council support the results of the presidential elections of 27th December 2020 in the Central African Republic and the officially elected president. They express their concern over the deteriorating military and political situation and the threat of government overthrow. Further, they confirm the importance of restoring state power throughout the entire territory of the country. The members of the Security Council express their deepest concern about the new outbreak of the Ebola disease in the Central African Republic. They urge the international community to provide vaccines and medical equipment to the people of CAR to combat the disease. The Security Council strongly opposes the violence and crimes committed by certain rebellious groups with the support of former President François Bozizé trying to undermine the electoral process, and condemns the violations of the Political Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation, signed by the Government of the Central African Republic and armed groups in Bangui on 6th February 2019. The Security Council urges all signatory parties to fully honour their commitments and join the path of dialogue and peace. The Security Council recalls that individuals or entities who are threatening the stabilization of the country may be targeted under a Security Council sanctions regime. Violence fueled by disinformation campaigns is also strongly condemned. The Security Council stresses the urgent need to end impunity in the CAR and to let justice prevail over perpetrators of violations of international humanitarian law and of violations and abuses of human rights. -

Trafficking in Transnistria: the Role of Russia

Trafficking in Transnistria: The Role of Russia by Kent Harrel SIS Honors Capstone Supervised by Professors Linda Lubrano and Elizabeth Anderson Submitted to the School of International Service American University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with General University Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree May 2009 Abstract After declaring de facto independence from the Republic of Moldova in 1992, the breakaway region of Transnistria became increasingly isolated, and has emerged as a hotspot for weapons and human trafficking. Working from a Realist paradigm, this project assesses the extent to which the Russian government and military abet trafficking in Transnistria, and the way in which Russia uses trafficking as a means to adversely affect Moldova’s designs of broader integration within European spheres. This project proves necessary because the existing scholarship on the topic of Transnistrian trafficking failed to focus on the role of the Russian government and military, and in turn did not account for the ways in which trafficking hinders Moldova’s national interests. The research project utilizes sources such as trafficking policy centers, first-hand accounts, trade agreements, non-governmental organizations, and government documents. A review of the literature employs the use of secondary sources such as scholarly and newspaper articles. In short, this project develops a more comprehensive understanding of Russia’s role in Moldovan affairs and attempts to add a significant work to the existing literature. -

Arms Embargoes Chapter

Sanctions Sans Commitment: An Assessment of UN Arms Embargoes By David Cortright, George A. Lopez, with Linda Gerber An impeccable logic makes arms embargoes a potentially powerful instrument in the array of United Nations (UN) peace- and security-building mechanisms. By denying aggressors and human rights abusers the implements of war and repression, arms embargoes contribute directly to preventing and reducing the level of armed conflict.1 There could hardly be a more appropriate tool for international peacemaking. Moreover, in constricting only selected weapons and military-related goods and services, and in denying these to ruling elites, their armies, and other violent combatants, arms embargoes constitute the quintessential example of a smart sanction. Not only do arms embargoes avoid doing harm to vulnerable and innocent civilian populations; the better the embargoes’ enforcement, the more innocent lives are likely to be saved. This powerful logic may explain why arms embargoes are the most frequently employed form of economic sanction. Since 1990, the UN Security Council has imposed mandatory arms embargoes in twelve of its fourteen sanctions cases. See the table “Selected Cases of Arms Embargoes, 1990-2001” for a complete listing of Security Council arms embargoes in the past decade. Only in the cases of Cambodia and Sudan did the Security Council choose not to apply a restriction on arms imports. In most cases arms embargoes were part of a broader package of sanctions measures. In some cases (Angola, Rwanda since 1995, and Sierra Leone since 1998) arms embargoes have been targeted against rebel movements fighting against an established government. In all other cases arms embargoes were applied against governments deemed to be violating human rights and posing a threat to international peace. -

The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: an Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes

Comment The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: An Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes Raymond Paretzkyt Introduction With reports of violence and unrest in the Republic of South Africa a daily feature in American newspapers, public attention in the United States has increasingly focused on a variety of American efforts to bring an end to apartheid.. Little discussed in the ongoing debate over imposi- tion of new measures is the sanction that the United States has main- tained for the past twenty-three years: the South African arms embargo. How effective has this sanction been in denying South Africa access to items with military utility? Are there ways to strengthen the arms em- bargo so that it achieves greater success? An evaluation of the embargo is complicated by the fact that there is no one place in which the laws implementing it can be found. Rather, the relevant regulations have been incorporated into the existing, com- plex scheme of U.S. trade law. This article offers a complete account of the laws and regulations implementing the embargo, analyzes the defects in the regulatory scheme, and recommends ways to strengthen the em- bargo. The first part outlines the background of the imposition of the embargo, while the next three parts examine the regulations that govern American exports to South Africa and explore the loopholes in these reg- ulations that hinder their effectiveness. Part II discusses items on the t J.D. Candidate, Yale University. 1. Congress recently imposed various sanctions on South Africa. See Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, Pub. -

The U.S. Arms Embargo of 1975–78 and Its Effects on The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2014-09 þÿThe U.S. arms embargo of 1975ÿ–1978 and its effects on the development of the Turkish defense industry Durmaz, Mahmut Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/43905 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE U.S. ARMS EMBARGO OF 1975–1978 AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE TURKISH DEFENSE INDUSTRY by Mahmut Durmaz September 2014 Thesis Advisor: Robert E. Looney Second Reader: Victoria Clement Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED September 2014 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE U.S. ARMS EMBARGO OF 1975–1978 AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE TURKISH DEFENSE INDUSTRY 6. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Service for Foreign Policy Instruments

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Service for Foreign Policy Instruments This list is subject to the legal notice at http://ec.europa.eu/geninfo/legal_notices_en.htm European Union Restrictive measures (sanctions) in force (Regulations based on Article 215 TFEU and Decisions adopted in the framework of the Common Foreign and Security Policy) This list has been updated on 7.7.2016 Related links: (previous update: 20.4.2016) Sanctions Overview Financial sanctions: Electronic consolidated list EU restrictive measures in force (updated 7.7.2016) 1/114 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Service for Foreign Policy Instruments This list is subject to the legal notice at http://ec.europa.eu/geninfo/legal_notices_en.htm Introduction Article 215 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) provides a legal basis for the interruption or reduction, in part or completely, of the Union’s economic and financial relations with one or more third countries, where such restrictive measures are necessary to achieve the objectives of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). This list presents the European Union's restrictive measures in force on the date mentioned on the cover page. It comprises: the legislative measures based on Article 215 TFEU and those based on the relevant provisions of the Treaty establishing the European Community (in the years prior to 1 December 2009: Articles 60 and 301) and the relevant CFSP Decisions and (prior to 1 December 2009) Common Positions, including those which merely provide for measures for which no specific Regulation was made, such as restrictions on admission. In Union law Regulations are directly applicable in all EU Member States. -

Bout, Viktor Et Al. S1 Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 17, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL, JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA PAUL KNIERIM OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-8244 U.S. ANNOUNCES NEW INDICTMENT AGAINST INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER VIKTOR BOUT AND AMERICAN CO-CONSPIRATOR FOR MONEY LAUNDERING, WIRE FRAUD, AND CONSPIRACY PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," and his associate RICHARD AMMAR CHICHAKLI, a/k/a "Robert Cunning," a/k/a "Raman Cedorov," for allegedly conspiring to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA") stemming from their efforts to purchase two aircraft from companies located in the United States, in violation of economic sanctions which prohibited such financial transactions. The Indictment unsealed today also charges BOUT and CHICHAKLI with money laundering conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and six separate counts of wire fraud, in connection with these financial transactions. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. Since BOUT's arrest, the United States has been actively pursuing his extradition from Thailand on a separate set of U.S. charges. Those charges allege that BOUT conspired to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. -

The EU Arms Embargo on China: a Swedish Perspective

The EU Arms Embargo on China: a Swedish Perspective JERKER HELLstrÖM FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency, is a mainly assignment-funded agency under the Ministry of Defence. The core activities are research, method and technology development, as well as studies conducted in the interests of Swedish defence and the safety and security of society. The organisation employs approximately 1000 personnel of whom about 800 are scientists. This makes FOI Sweden’s largest research institute. FOI gives its customers access to leading-edge expertise in a large number of fields such as security policy studies, defence and security related analyses, the assessment of various types of threat, systems for control and management of crises, protection against and management of hazardous substances, IT security and the potential offered by new sensors. FOI Swedish Defence Research Agency Phone: +46 8 555 030 00 www.foi.se FOI-R--2946--SE User report Defence Analysis Defence Analysis Fax: +46 8 555 031 00 ISSN 1650-1942 January 2010 SE-164 90 Stockholm Jerker Hellström The EU Arms Embargo on China: a Swedish Perspective Cover illustration: Dagens Nyheter 5, 6 June 1989, the Times 28 June 1989 FOI-R--2946--SE Title The EU Arms Embargo on China: a Swedish Perspective Report no FOI-R--2946--SE Report Type User report Month January Year 2010 Pages 60 ISSN ISSN 1650-1942 Customer Swedish Ministry of Defence Project no A12004 Approved by Maria Lignell Jakobsson FOI, Totalförsvarets Forskningsinstitut FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency Avdelningen för Försvarsanalys Department of Defence Analysis 164 90 Stockholm SE-164 90 Stockholm Summary This report highlights the background of the EU arms embargo on China; how the issues of the design and the possible lifting of the embargo have been handled in Brussels; and in what respect political interpretations and economic interests have influenced exports of military equipment to China from EU member states. -

Targeting Spoilers the Role of United Nations Panels of Experts

Targeting Spoilers The Role of United Nations Panels of Experts Alix J. Boucher and Victoria K. Holt Report from the Project on Rule of Law in Post-Conflict Settings Future of Peace Operations January 2009 Stimson Center Report No. 64 2 | Alix J. Boucher and Victoria K. Holt Copyright © 2009 The Henry L. Stimson Center Report Number 64 Cover photo: United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (UNOCI) peacekeepers conduct arms embargo inspections on government forces in western Côte d'Ivoire. Cover design by Shawn Woodley All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from the Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19 th Street, NW 12 th Floor Washington, DC 20036 telephone: 202.223.5956 fax: 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Targeting Spoilers: The Role of United Nations Panels of Experts | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................................4 Preface ..............................................................................................................................................5 List of Acronyms ..............................................................................................................................8 List of Figures, Tables, and Sidebars ..............................................................................................10 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................11 -

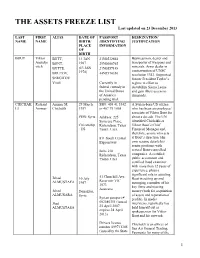

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last Updated on 23 December 2013

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last updated on 23 December 2013 LAST FIRST ALIAS DATE OF PASSPORT DESIGNATION/ NAME NAME BIRTH/ /IDENTIFYING JUSTIFICATION PLACE INFORMATION OF BIRTH BOUT Viktor BUTT, 13 JAN 21N0532664 Businessman, dealer and Anatolje BONT, 1967 29N0006765 transporter of weapons and vitch minerals. Arms dealer in BUTTE, (13 JAN 21N0557148 1970) contravention of UNSC BOUTOV, 44N3570350 resolution 1343. Supported SERGITOV former President Taylor’s Vitali Currently in regime in effort to federal custody in destabilize Sierra Leone the United States and gain illicit access to of America diamonds. pending trial. CHICHAK Richard Ammar M. 29 March SSN: 405 41 5342 A Syrian-born US citizen LI Ammar Chichakli 1959 or 467 79 1065 who has been an employee/ associate of Viktor Bout for POB: Syria Address: 225 about a decade. The UN Syracuse Place, identified Chichakli as Citizenship Richardson, Texas Viktor Bout’s Chief : US 75081, USA Financial Manager and, therefore, as one who acts 811 South Central at Bout’s direction. His Expressway own resume details his senior positions with several Bout-controlled Suite 210 Richardson, Texas companies. A certified 75080, USA public accountant and certified fraud examiner with more than 12 years of experience, plays a significant role in assisting 51 Churchill Ave. Jehad 10 July Bout in setting up and Reservoir VIC ALMUSTAFA 1967 managing a number of his 3073 key firms and moving Australia Jehad Deirazzor, money (both for acquisition ALMUSARA Syria of assets and reparation of Syrian passport # profits). In media Jhad 002680351 (issued interviews, reportedly has ALMUSTASA 25 April 2007, held himself out as expires 24 April spokesperson for Viktor 2013) Bout and his network. -

Bout Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE May 6, 2008 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA GARRISON COURTNEY OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-7977 U.S. ANNOUNCES INDICTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER FOR CONSPIRACY TO KILL AMERICANS AND RELATED TERRORISM CHARGES MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," for, among other things, conspiring to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. BOUT was arrested by Thai authorities on a provisional arrest warrant on April 9, 2008, based on a complaint filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, charging conspiracy to provide material support or resources to a designated foreign terrorist organization. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. According to the Indictment unsealed today in Manhattan federal court: BOUT, an international weapons trafficker since the 1990s, has carried out his weapons-trafficking business by assembling a fleet of cargo airplanes capable of transporting weapons and military equipment to various parts of the world, including Africa, South America and the Middle East.