Africa in Arms Taking Stock of Efforts for Improved Arms Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trafficking in Transnistria: the Role of Russia

Trafficking in Transnistria: The Role of Russia by Kent Harrel SIS Honors Capstone Supervised by Professors Linda Lubrano and Elizabeth Anderson Submitted to the School of International Service American University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with General University Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree May 2009 Abstract After declaring de facto independence from the Republic of Moldova in 1992, the breakaway region of Transnistria became increasingly isolated, and has emerged as a hotspot for weapons and human trafficking. Working from a Realist paradigm, this project assesses the extent to which the Russian government and military abet trafficking in Transnistria, and the way in which Russia uses trafficking as a means to adversely affect Moldova’s designs of broader integration within European spheres. This project proves necessary because the existing scholarship on the topic of Transnistrian trafficking failed to focus on the role of the Russian government and military, and in turn did not account for the ways in which trafficking hinders Moldova’s national interests. The research project utilizes sources such as trafficking policy centers, first-hand accounts, trade agreements, non-governmental organizations, and government documents. A review of the literature employs the use of secondary sources such as scholarly and newspaper articles. In short, this project develops a more comprehensive understanding of Russia’s role in Moldovan affairs and attempts to add a significant work to the existing literature. -

2134 ISS Monograph 116 Sierra Leone.Indd

ISS MONOGRAPH No 116 PERPETUATING POWER: SMALL ARMS IN POST-CONFLICT SIERRA LEONE AND LIBERIA It is estimated that between eight and ten million small arms are circulating in West Africa; the real number is probably higher. Civil war in the Mano River Basin, where resources such as diamonds, rubber, and timber create buying power for political factions of all persuasions, has sustained the international flow of weapons to the region. With United Nations missions in both Sierra Leone and Liberia and the accompanying disarmament and demobilisation in both places having come to an end, markets for small arms and light weapons in West Africa are still open for business. Disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration processes have created their own weapons markets across borders as prices for handing over a weapon vary from country to country. State-centred solutions to illicit arms proliferation do not work when the state in question cannot fund traditional security operations. Borders are porous, and though they should be closed or better monitored, that is not a short- or medium-term option. Instead, this monograph looks at the factors behind the demand for weapons in Sierra Leone and Liberia, focusing on the buyer side of the market to determine whether proliferation can be stemmed, or at least slowed down, through more creative measures. Price: R20-00 PPERPETRATINGERPETRATING PPOWEROWER SMALL ARMS IN POST-CONFLICT SIERRA LEONE AND LIBERIA TAYA WEISS The vision of the Institute for Security Studies is one of a stable and peaceful Africa characterised by human rights, the rule of law, democracy and collaborative security. -

Liberia:Liberia: Backback Toto Thethe Futurefuture What Is the Future of Liberia’S Forests and Its Effects on Regional Peace?

Recommendations contained on page 1 Liberia:Liberia: BackBack toto thethe FutureFuture What is the future of Liberia’s forests and its effects on regional peace? A Report by Global Witness. May 2004 Liberia—Back to the Future Recommendations The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) should: The United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) should: G Maintain the embargo on the export and transport of Liberian timber, and its import into G Ensure that regular patrols are carried out in both other countries. The embargo should remain in interior and border areas to ensure the collection place until it can be demonstrated that the of comprehensive intelligence on trafficking Liberian timber trade does not contribute to activities and abuses against the civilian national and regional insecurity. population. G Utilise UNMIL to secure Liberia’s lucrative G Work closely with the International Criminal natural resources, assess and monitor any existing Court (ICC) to determine how, during the course and likely cross-border land and sea-based of carrying out its duties, UNMIL can smuggling routes, and coordinate the region’s UN mainstream data-collection to include information peacekeeping forces and national military forces to that may be of use for potential war crimes create more effective border security and prevent tribunals. cross-border trafficking of weapons, mercenaries G Engage local Liberian NGOs in policy-setting and and natural resources. decision-making processes in order to ensure G Amend the Liberian DDRR mandate to thorough and effective implementation of its incorporate foreign nationals fighting in Liberia mandate. into national or sub-regional disarmament programmes. -

Bout, Viktor Et Al. S1 Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE FEBRUARY 17, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL, JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA PAUL KNIERIM OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-8244 U.S. ANNOUNCES NEW INDICTMENT AGAINST INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER VIKTOR BOUT AND AMERICAN CO-CONSPIRATOR FOR MONEY LAUNDERING, WIRE FRAUD, AND CONSPIRACY PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," and his associate RICHARD AMMAR CHICHAKLI, a/k/a "Robert Cunning," a/k/a "Raman Cedorov," for allegedly conspiring to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act ("IEEPA") stemming from their efforts to purchase two aircraft from companies located in the United States, in violation of economic sanctions which prohibited such financial transactions. The Indictment unsealed today also charges BOUT and CHICHAKLI with money laundering conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and six separate counts of wire fraud, in connection with these financial transactions. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. Since BOUT's arrest, the United States has been actively pursuing his extradition from Thailand on a separate set of U.S. charges. Those charges allege that BOUT conspired to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. -

Report on Arms Trafficking in the Border Regions Of

REPORT ON ARMS TRAFFICKING IN THE BORDER REGIONS OF SUDAN, UGANDA AND KENYA (A case Study of Uganda: North, Northeastern & Eastern) By Action For Development of Local Communities (ADOL) WITH SUPPORT FROM SWEDISH GOVERNMENT AND ACTION OF CHURCHES TOGETHER (ACT), NETHERLANDS. APRIL - JUNE, 2001. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................. 3 1.1. BACKGROUND 7 1.2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES, COVERAGE AND METHODOLOGY 8 2.0. RESEARCH FINDINGS ............................................................................ 10 2.1 MARKETS 10 2.2 ROUTES AND MODES OF ARMS TRAFFICKING 14 Map 2 showing Gun Market Belts 15 2.2 SOURCES OF SMALL ARMS AND AMMUNITIONS 16 2.3 DEALERS AND BUYERS OF SMALL ARMS AND AMMUNITIONS 17 2.4 NETWORKS AND OTHER METHODS OF ARMS ACQUISITION 18 Diagram 1: CURRENT NETWORK OF GUNS AND AMMUNITION SALES 20 2.5 EFFECTS OF GUN TRAFFICKING ON COMMUNITIES 21 2.6 EFFORTS TO CURB GUN TRAFFICKING 21 2.7 IMPACT OF GUN TRAFFICKING ON LOCAL ECONOMIES 23 3.0 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................. 25 APPENDICES .................................................................................................... 26 APPENDIX 1 26 APPENDIX 2 28 3 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The study was conducted in the districts of Moroto, Kotido, Nakapiripirit, Katakwi, Soroti, Kumi, Lira, Kitgum, Gulu, Pader, Adjumani, Moyo, Yumbe, and Kapchorwa with the following objectives: ♦ Collect first hand data from local authorities, community leaders, businessmen, police personnel and the army on the sources and causes of arms trafficking in the border regions of Sudan, Uganda and Kenya. ♦ Collect information on the location of gun markets, the quantity of traded arms, and the motives for trading in arms and ammunitions as well as the networks in which the gun traffickers operate. -

Reducing Illegal Firearms Trafficking

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Assistance Monograph Reducing Illegal Firearms Trafficking Promising Practices and Lessons Learned Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street NW. Washington, DC 20531 Janet Reno Attorney General Daniel Marcus Acting Associate Attorney General Mary Lou Leary Acting Assistant Attorney General Nancy E. Gist Director, Bureau of Justice Assistance Office of Justice Programs World Wide Web Home Page www.ojp.usdoj.gov Bureau of Justice Assistance World Wide Web Home Page www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA For grant and funding information contact U.S. Department of Justice Response Center 1–800–421–6770 This document was prepared by Police Executive Research Forum, supported by coopera- tive agreement number 96–DD–BX–K005, awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Of- fice of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not nec- essarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Bureau of Justice Assistance Reducing Illegal Firearms Trafficking Promising Practices and Lessons Learned July 2000 Monograph NCJ 180752 Reducing Illegal Firearms Trafficking Foreword Throughout the United States, violence involving firearms remains at an alarmingly high rate. -

Arms Trafficking Will Even Give Them Direct Access—At a Lower Cost—To Weapons

98903 Trafficking and Fragility in West Africa Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Côme Dechery and Laura Ralston Public Disclosure Authorized Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Group World Bank 2015 1 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 What is Trafficking? .................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Regional criminal markets and trafficking in West Africa ............................................................ 5 1.3 The region’s evolving criminal economy .................................................................................... 5 1.4 Internal factors: Crime and governance in West Africa ............................................................... 6 1.5 External factors: Market trends in worldwide trafficking ............................................................ 7 1.6 The routes and hubs of West African trafficking ......................................................................... 9 1.7 The prevalence and nature of trafficking flows in the region .................................................... 12 2. Five channels between trafficking and fragility: Trafficking and its impact on West Africa .. 13 2.1 Channel 1—A source -

International Regional and Subregional Instruments

KENYA NATIONAL FOCAL POINT AND LIGHT WEAPONS SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS PROLIFERATION PRESENTATION ON NATIONAL DATA ON ILLICIT ARMS FLOW AND IMPACT ON POLICY 1 Arms Trafficking flows in Kenya Much of the Great Lakes region and the Horn of Africa is awash with guns, predominantly small arms, and a large number of those weapons spill over into Kenya. Since the late 1970s countries bordering Kenya to the north (Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, and Uganda) among them have experienced long periods of unrest and internal armed conflict. Fighters from wars in these countries are a prime source of weapons brought into Kenya, which they often sell for subsistence. In addition, kinship ties among pastoralist communities that straddle international borders can facilitate the movement of firearms from one side to another, as well as the spread of localized conflicts. Kenya is vulnerable to illicit weapons trafficking through the same channels used for legal arms shipments.The country has long been a major transit point for illegal weapons shipments destined to war-torn countries in the Great Lakes region of Africa. The existence of an abusive armed conflict in the recipient country in some circumstances risks the weapons being diverted to an unauthorized third party (or of spilling back into Kenya) unscrupulous arms brokers and shipping agents in most cases use false documents, misdeclare cargo, file false flight plans, hide weapons in secret compartments in motor vehicles and shipping containers, and other covert tactics to traffic weapons undetected. However, Kenyan customs authorities take a number of steps to rein in such illegalities, but better techniques and equipment are required to more systematically halt undeclared arms shipments. -

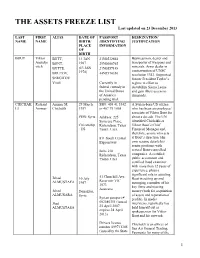

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last Updated on 23 December 2013

THE ASSETS FREEZE LIST Last updated on 23 December 2013 LAST FIRST ALIAS DATE OF PASSPORT DESIGNATION/ NAME NAME BIRTH/ /IDENTIFYING JUSTIFICATION PLACE INFORMATION OF BIRTH BOUT Viktor BUTT, 13 JAN 21N0532664 Businessman, dealer and Anatolje BONT, 1967 29N0006765 transporter of weapons and vitch minerals. Arms dealer in BUTTE, (13 JAN 21N0557148 1970) contravention of UNSC BOUTOV, 44N3570350 resolution 1343. Supported SERGITOV former President Taylor’s Vitali Currently in regime in effort to federal custody in destabilize Sierra Leone the United States and gain illicit access to of America diamonds. pending trial. CHICHAK Richard Ammar M. 29 March SSN: 405 41 5342 A Syrian-born US citizen LI Ammar Chichakli 1959 or 467 79 1065 who has been an employee/ associate of Viktor Bout for POB: Syria Address: 225 about a decade. The UN Syracuse Place, identified Chichakli as Citizenship Richardson, Texas Viktor Bout’s Chief : US 75081, USA Financial Manager and, therefore, as one who acts 811 South Central at Bout’s direction. His Expressway own resume details his senior positions with several Bout-controlled Suite 210 Richardson, Texas companies. A certified 75080, USA public accountant and certified fraud examiner with more than 12 years of experience, plays a significant role in assisting 51 Churchill Ave. Jehad 10 July Bout in setting up and Reservoir VIC ALMUSTAFA 1967 managing a number of his 3073 key firms and moving Australia Jehad Deirazzor, money (both for acquisition ALMUSARA Syria of assets and reparation of Syrian passport # profits). In media Jhad 002680351 (issued interviews, reportedly has ALMUSTASA 25 April 2007, held himself out as expires 24 April spokesperson for Viktor 2013) Bout and his network. -

Bout Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE May 6, 2008 YUSILL SCRIBNER, REBEKAH CARMICHAEL PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA GARRISON COURTNEY OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS (202) 307-7977 U.S. ANNOUNCES INDICTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL ARMS DEALER FOR CONSPIRACY TO KILL AMERICANS AND RELATED TERRORISM CHARGES MICHAEL J. GARCIA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and MICHELE M. LEONHART, the Acting Administrator of the United States Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced today the unsealing of an Indictment against international arms dealer VIKTOR BOUT, a/k/a "Boris," a/k/a "Victor Anatoliyevich Bout," a/k/a "Victor But," a/k/a "Viktor Budd," a/k/a "Viktor Butt," a/k/a "Viktor Bulakin," a/k/a "Vadim Markovich Aminov," for, among other things, conspiring to sell millions of dollars worth of weapons to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (the "FARC") -- a designated foreign terrorist organization based in Colombia -- to be used to kill Americans in Colombia. BOUT was arrested by Thai authorities on a provisional arrest warrant on April 9, 2008, based on a complaint filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, charging conspiracy to provide material support or resources to a designated foreign terrorist organization. BOUT has been in custody in Thailand since March 6, 2008. According to the Indictment unsealed today in Manhattan federal court: BOUT, an international weapons trafficker since the 1990s, has carried out his weapons-trafficking business by assembling a fleet of cargo airplanes capable of transporting weapons and military equipment to various parts of the world, including Africa, South America and the Middle East. -

Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan

32 Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan By Jonah Leff and Emile LeBrun Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2014 First published in May 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Tania Inowlocki Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-9700897-1-1 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 32 Contents List of boxes, figures, maps, and tables .......................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Viktor Bout Arrested

VIKTOR BOUT ARRESTED Curious. The Thais just arrested the noted Russian arms dealer, Viktor Bout. For years, Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout has made millions of dollars allegedly delivering weapons and ammunition to warlords and militants. Officials believe many of his activities may be illegal, and on Thursday, Thai police announced his arrest. Bout, 41, has made his deliveries to Africa, Asia and the Mideast, using obsolete or surplus Soviet-era cargo planes. [snip] According to U.S. officials, Bout — a former Soviet air force officer who speaks multiple languages — has what is reputed to be the largest private fleet of Soviet-era cargo aircraft in the world. Bout acquired the planes shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the U.S. Department of Treasury said in 2005. At that time, the U.S. Treasury announced it was freezing the assets of Bout and his associates who are all tied to former Liberian President Charles Taylor. Taylor is currently on trial at the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague. Intelligence officials said he shipped large quantities of small arms to civil wars across Africa and Asia, often taking diamonds in payment from West African fighters. I say, "curious," because I doubt this could have happened without US approval–as the promise of an "announcement" in NY later today suggests. A formal announcement on his arrest is expected later in the day in New York. And it appears that actual warrant came from our DEA–in connection with Columbia’s FARC. Bout, the target of an international arrest warrant and U.S.