Women and Population Flows in India by Paula Banerjee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kadamattathachan (1966 Film)

Kadamattathachan (1966 film) Kadamattathachan is a 1966 Indian Malayalam film, directed by KR Nambiar and produced by Rt Rev Fr George Thariyan. The film stars Sukumari, Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair, Anujan Kurichi and Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai in lead roles. The film had musical score by V. Dakshinamoorthy.[1][2][3]. Kadamattathachan is a 1984 Indian Malayalam film, directed and produced by NP Suresh. The film stars Prem Nazir, Srividya, Hari and Prathapachandran in lead roles. The film had musical score by A. T. Ummer and Traditional. Prem Nazir as Fr.Paulose/Kadamattathu Kathanar. Srividya as Kaliyankattu Neeli. Hari as Kunchavan Potti. Prathapachandran as Valiachan. K. P. A. C. Azeez as Kattummooppan. Bobby Kottarakkara as Thirumeni's Karyasthan. C. I. Paul as Pathrose. Janardanan as Aliyar. Starring: Sukumari, Thikkurissy Sukumaran Nair, Prem Nazir and others. Kadamattathachan is a 1966 Indian Malayalam film, directed by KR Nambiar and produced by Rt Rev Fr George Thariyan. The film stars Sukumari, Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair, Anujan Kurichi and Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai in lead roles. The film had musical score by V. Dakshinamoorthy. Kadamattathachan is a 1966 Indian Malayalam film, directed by KR Nambiar and produced by George Thariyan. The film stars Sukumari, Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair, Anujan Kurichi and Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai in lead roles. The film had musical score by V. Dakshinamoorthy.[1][2][3]. For faster navigation, this Iframe is preloading the Wikiwand page for Kadamattathachan (1966 film). Home. News. National & Gulf Center for Evidence Based Health Practice When We Were Lions 12 Golden Ducks Gayle, North Yorkshire Maisha Film Lab Andrew Scott (judge) Start Here https://t.co/FV56fzFdla https://www.facebook.com/Kadamattathachan-1966-film https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/Kadamattathachan-1966-film/id460373590 https://www.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2F.... -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

CII-ITC Sustainability Awards 2008 Chemplast Sanmar Gets Recognition in the Large Business Category Awards

1 Sanmar Holdings Limited Sanmar Chemicals Corporation Sanmar Engineering Corporation Chemplast Sanmar Limited BS&B Safety Systems (India) Limited PVC Flowserve Sanmar Limited Chlorochemicals Sanmar Engineering Services Limited Trubore Piping Systems Fisher Sanmar Limited TCI Sanmar Chemicals LLC (Egypt) Regulator Valves Tyco Sanmar Limited Sanmar Metals Corporation Xomox Sanmar Limited Sanmar Foundries Limited Pacific Valves Division Sand Foundry Investment Foundry Sanmar Speciality Chemicals Limited Machine Shop ProCitius Research Matrix Metals LLC Intec Polymers Keokuk Steel Castings Company (USA) Performance Chemicals Richmond Foundry Company (USA) Bangalore Genei Acerlan Foundry (Mexico) Cabot Sanmar Limited NEPCO International (USA) Sanmar Ferrotech Limited Eisenwerk Erla GmBH (Germany) Sanmar Shipping Limited The Sanmar Group 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. Tel.: + 91 44 2812 8500 Fax: + 91 44 2811 1902 2 In this issue... Momentous Moments MNC Flying to the Moon 4 MNC Celebrates 19th Anniversary 28 5th National Workshop on Early Intervention for Cover Story Mental Retardation 29 Sanmar’s Egyptian Sojourn 8 Social Responsibility Guest Column India’s Environment Ambassador Bata by Choice -Thomas G Bata 12 Voyages to the Arctic 30 A New Financial World Order - Arvind Subramanian 15 CII-Tsunami Rehabilitation Scorecard 32 Celebrating Art Chemplast Sanmar Distributes Rice in Hurricane- ravaged Villages in Cuddalore & Karaikal 34 Strumming to Spanish Music 19 Renovation of Park at Karaikal 35 Sruti Magazine Celebrates Silver Jubilee 20 The First Mrs Madhuram Narayanan Endowment Lecture 36 Pristine Settings Around Sanmar 22 Events Awards Sanmar Stands Tall 37 Flowserve Sanmar’s Training Centre 24 Trubore Dealers’ Meet 25 Legends from the South The 9th AIMA-Sanmar National Management Quiz 26 Padmini 42 Matrix can be viewed at www.sanmargroup.com Designed and edited by Kalamkriya Limited, 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. -

Anuraagakkodathi

Anuraagakkodathi Anuraagakkodathi is a 1982 Indian Malayalam film, directed by Hariharan and produced by Areefa Hassan. The film stars Shankar, Rajkumar, Ambika and Madhavi in lead roles. The film had musical score by A. T. Ummer. Shankar as Shivadasan. Rajkumar as Ravi. Ambika as Susheela. Madhavi as Anuradha. Sukumari as Meenakshi. Prathapachandran as Minister Chandrasekharan. Bahadoor as Muthangakuzhi Gopalan. C. I. Paul as Shivaraman. Kuthiravattam Pappu as Gopi. Lalithasree. Anuraagakkodathi's wiki: Anuraagakkodathi is a 1982 Indian Malayalam film, directed by Hariharan and produced by Areefa Hassan. The film stars Shankar, Rajkumar, Ambika and Madhavi in lead roles. The film had musical score by A. T. Ummer.[2][3][4]CastShankar as ShivadasanRajkumar. Reference Links For This Wiki. All information for Anuraagakkodathi's wiki comes from the below links. Any source is valid, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Anuraagakkodathi Songs Download- Listen Malayalam Anuraagakkodathi MP3 songs online free. Play Anuraagakkodathi Malayalam movie songs MP3 by K.J. Yesudas and download Anuraagakkodathi songs on Gaana.com. Anuraagakkodathi. Anuraagakkodathi is a 1982 Indian Malayalam film, directed by Hariharan and produced by Areefa Hassan. The film stars Shankar, Rajkumar, Ambika and Madhavi in lead roles. The film had musical score by A. T. Ummer.[1][2][3]. Anuraagakkodathi. Directed by. Hariharan. Anuraagakkodathi is a 1982 Indian Malayalam film, directed by Hariharan and produced by Areefa Hassan. The film stars Shankar, Rajkumar, Ambika and Madhavi in lead roles. The film had musical score by A. T. Ummer. Shankar as Shivadasan. Rajkumar as Ravi. Ambika as Susheela. Madhavi as Anuradha. Sukumari as Meenakshi. -

Vida Parayum Munbe Malayalam Movie Torrent Download

vida parayum munbe malayalam movie torrent download 6 Movies Of John Paul Which Prove That He Is A Master Writer! We recently heard that renowned scriptwriter John Paul is making a comeback to films with Major Ravi's upcoming film which would have Mohanlal in the lead role. John Paul, is one of the most versatile scriptwriters in the industry and his comeback is indeed a good sign for Malayalam cinema. Here, we list some of the best works of John Paul, so far. Chamaram (1980) Chamaram directed by Bharathan had the script written by John Paul. The film went on to become a trendsetter, by narrating the story of an affair between a student and a lecturer. This was a path- breaking movie and won great applause. Yathra (1985) This definitely has to be one of the finest works of John Paul, so far. Yathra was a path-breaking movie and the film directed by Balu Mahendra gave Mammootty one of his finest roles in his initial days of film career. The film won both critical and commercial success. Palangal (1981) Palangal , which is best remembered for the amazing craftsmanship of director Bharathan, was written by John Paul. His amazing sense of characterisations can be noted through this movie. Oru Minnaaminunginte Nurunguvettam (1987) John Paul yet gain showed his mastery by scripting the heart-wrenching tale of an aged couple. This film directed by Bharathan went on win two Kerala State Film Awards. Vida Parayum Munpe (1981) This film is considered to be one of the best movies of Prem Nazir. -

Joint Secretary in the Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Vacancy No

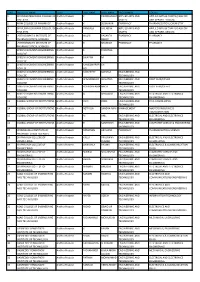

Joint Secretary in the Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Vacancy No. 21025102406) Sl. Roll Appl. No. Name No. No. 1 1 19910011409 ABHISHEK 2 2 19910000680 ABHISHEK KUMAR 3 3 19910007173 ABHISHEK SRIVASTAVA 4 4 19910013104 ADITYA GUPTA 5 5 19910014883 AJAY ANDREWS CHERAYATH 6 6 19910013196 AJI VARGHESE 7 7 19910009612 ALOK GUPTA 8 8 19910004840 AMBUJ KUMAR SINHA 9 9 19910013027 AMIT BHARTI 10 10 19910007252 AMIT BHATNAGAR 11 11 19910005012 AMIT SHARMA 12 12 19910001299 AMIT KUMAR SINGH 13 13 19910002396 AMOL DATT 14 14 19910014872 ANAND BALKRISHNA KOLWALKAR 15 15 19910014835 ANAND KISHORE CHATURVEDI 16 16 19910015481 ANAND KUMAR SHARMA 17 17 19910002876 ANIRBAN BHAUMIK 18 18 19910011627 ANIRUDDHA VILAS SHAHAPURE 19 19 19910013551 ANOOP SOMAN 20 20 19910000501 ANSHUL MAHESHWARI 21 21 19910012796 ANSHUL MISHRA 22 22 19910013516 ANUP SOOD 23 23 19910009367 ANURAG KUMAR 24 24 19910015213 ARIVARASU SELVARAJ 25 25 19910001820 ARJUN KUMAR SINGH 26 26 19910006235 ARUN GOEL 27 27 19910011465 ARVIND BHISIKAR 28 28 19910003441 ASFDASF 29 29 19910002902 ASHISH BHAGAT 30 30 19910013634 ASHISH MALIK 31 31 19910008417 ASHUTOSH SHARMA 32 32 19910012472 ASTHA PANDEY 33 33 19910000114 ATUL KUMAR MALIK 34 34 19910004964 BHALCHANDRA PARSHURAM NAMJOSHI 35 35 19910012288 CHITRA KALYANASUNDARAM 36 36 19910015392 COMMANDER ANURAG SAXENA 37 37 19910004810 DEBABRATA DAS 38 38 19910008900 DEBASHISH CHAKRABARTY 39 39 19910010229 DEBASISH BISWAS 40 40 19910001040 DEEPAK CHANDA 41 41 19910015299 DEEPAK KUMAR 42 42 19910000767 DEEPAK KUMAR SHARMA -

Twenty 20 Malayalam Full Movie

Twenty 20 malayalam full movie Continue Twenty:20Official theatrical posterFoshiProduced byDileep Written byUdayakrishnaSiby K. ThomasStarringMohanlalMammoottySuresh GopiJayaramDileepMusic fromSur PetereshsBerny IgnatiusCinematographyP.SukumarEditedRan by Abraham Abraham and production DistributedManjunatha release Kalasangham FilmsRelease date November 5, 2008 (2008-11-05) Duration 165 minutesCountryIndiaLanguageMalayalamBudget₹7 crore (US$980,000)Box officeest. ₹32.6 crora ($4.6 million) is a 2008 Indian action film in Malayalam, written by Udayakrishna and Sibi K. Thomas and directed by Josh. The film stars Mohanlal, Mammutti, Suresh Gopi, Jayaram and Dillep, and was produced and distributed by actor Dillep through Graand Production and Manjunatha Release. The film was produced on behalf of the Association of Malayalam Film Chronicles (AMMA) as a fundraiser to financially support actors who are struggling in the Malayalam film industry. All AMMA members worked without pay to raise funds for their Social Security programs. The film features an ensemble of actors, which includes almost all AMMA artists. The music was written by Bernie-Ignatius and Suresh Peters. The share of the first two weeks of the film's distributors was ₹5.72 crore ($800,000). The film managed to gain a foothold in the third position (with 7 prints, 4 in Chennai) in the box office of Tamil Nadu in the first week. The total number of introductory engravings produced inside Kerala was 117; some 25 prints were released outside Kerala on November 21, 2008, including 4 prints in the United States and 11 engravings in the UAE. The film grossed a total of ₹32.6 kronor ($4.6 million). It was the highest-grossing film in Malayalam cinema until 2013. -

Aesthetics As Resistance: Rasa, Dhvani, and Empire in Tamil “Protest” Theater

AESTHETICS AS RESISTANCE: RASA, DHVANI, AND EMPIRE IN TAMIL “PROTEST” THEATER BY DHEEPA SUNDARAM DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Palencia-Roth, Chair Professor Rajeshwari Pandharipande, Director of Research Professor Indira Viswanathan Peterson, Mount Holyoke College Associate Professor James Hansen Abstract Aesthetics as Resistance: Rasa, Dhvani, and Empire in Modern Tamil “Protest” Theater addresses questions concerning the role of aesthetics in the development, production, and impact of Tamil “Protest” Theater (1900-1930) on the success of the Indian anticolonial movement in the colonial Tamil state. In addition, I explore the possibility for a Modern Tamil aesthetic paradigm that arises from these syncretic plays, which borrow from both external and indigenous narrative and dramaturgical traditions. I begin with the following question, “Can aesthetic “relishing” (rasasvāda) be transformed into patriotic sentiment and fuel anticolonial resistance?” Utilizing Theodore Baskaran’s The Message Bearers, which examines the development and production of anticolonial media in the colonial Tamil state as point of departure, my research interrogates Tamil “popular” or “company” drama as a successful vehicle for evoking anticolonial sentiment. In this context, I posit the concept of “rasa- consciousness” as the audience’s metanarrative lens that transforms emotive cues and signposts in the dramatic work into sentiment through a process of aesthetic "remembering.” This lens is constituted through a complex interaction between culture, empire, and modernity that governs the spectator’s memorializing process. The culturally-determined aesthetic “lens” of Tamil spectator necessitates a culture-specific messaging system by anticolonial playwrights that links the dramatic outcome with feelings of nationalism and patriotism. -

Mohanlal Filmography

Mohanlal filmography Mohanlal Viswanathan Nair (born May 21, 1960) is a four-time National Award-winning Indian actor, producer, singer and story writer who mainly works in Malayalam films, a part of Indian cinema. The following is a list of films in which he has played a role. 1970s [edit]1978 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes [1] 1 Thiranottam Sasi Kumar Ashok Kumar Kuttappan Released in one center. 2 Rantu Janmam Nagavally R. S. Kurup [edit]1980s [edit]1980 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Manjil Virinja Pookkal Poornima Jayaram Fazil Narendran Mohanlal portrays the antagonist [edit]1981 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Sanchari Prem Nazir, Jayan Boban Kunchacko Dr. Sekhar Antagonist 2 Thakilu Kottampuram Prem Nazir, Sukumaran Balu Kiriyath (Mohanlal) 3 Dhanya Jayan, Kunchacko Boban Fazil Mohanlal 4 Attimari Sukumaran Sasi Kumar Shan 5 Thenum Vayambum Prem Nazir Ashok Kumar Varma 6 Ahimsa Ratheesh, Mammootty I V Sasi Mohan [edit]1982 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Madrasile Mon Ravikumar Radhakrishnan Mohan Lal 2 Football Radhakrishnan (Guest Role) 3 Jambulingam Prem Nazir Sasikumar (as Mohanlal) 4 Kelkkatha Shabdam Balachandra Menon Balachandra Menon Babu 5 Padayottam Mammootty, Prem Nazir Jijo Kannan 6 Enikkum Oru Divasam Adoor Bhasi Sreekumaran Thambi (as Mohanlal) 7 Pooviriyum Pulari Mammootty, Shankar G.Premkumar (as Mohanlal) 8 Aakrosham Prem Nazir A. B. Raj Mohanachandran 9 Sree Ayyappanum Vavarum Prem Nazir Suresh Mohanlal 10 Enthino Pookkunna Pookkal Mammootty, Ratheesh Gopinath Babu Surendran 11 Sindoora Sandhyakku Mounam Ratheesh, Laxmi I V Sasi Kishor 12 Ente Mohangal Poovaninju Shankar, Menaka Bhadran Vinu 13 Njanonnu Parayatte K. -

S.No Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme

S.NO INSTITUTE NAME STATE LAST NAME FIRST NAME PROGRAMME COURSE 1 SRI VENKATESHWARA COLLEGE OF Andhra Pradesh K PARMASIVAM APPLIED ARTS AND APPLIED ARTS & CRAFTS (FASHION FINE ARTS CRAFTS AND APPAREL DESIGN) 2 MRM COLLEGE OF PHARMACY Andhra Pradesh K SUBHAKAR PHARMACY PHARMACEUTICAL CHEMISTRY 3 SRI VENKATESHWARA COLLEGE OF Andhra Pradesh VANGALA UPENDRA APPLIED ARTS AND APPLIED ARTS & CRAFTS (FASHION FINE ARTS CRAFTS AND APPAREL DESIGN) 4 JYOTHISHMATHI INSTITUTE OF Andhra Pradesh AILURI VASANTA PHARMACY PHARMACY PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES REDDY 5 JYOTHISHMATHI INSTITUTE OF Andhra Pradesh B SHANKAR PHARMACY PHARMACY PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES 6 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh S POOJITHA COLLEGE 7 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh SWAPNA M COLLEGE 8 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh KAMESWARAR CH COLLEGE AO 9 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh ANISHETTY MANASA ENGINEERING AND COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 10 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh BOMMIREDDY SUSHITHA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 11 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh KOLACHALAMA NAGA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 12 SRIDEVI WOMEN'S ENGINEERING Andhra Pradesh G SRIVASAVI ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 13 GLOBAL GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS Andhra Pradesh DEVI DDNL ENGINEERING AND CIVIL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY 14 GLOBAL GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS Andhra Pradesh NETHULA SANDYA RANI MANAGEMENT MASTERS IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION 15 GLOBAL GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS Andhra Pradesh -

Hijra's and Their Social Life in South Asia

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-4, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Hijra’s and their social life in South Asia. DelliSwararao Konduru(M COM, M.A (Socio Cultural Anthropology), C G T), Research Officer, N.I.E (I C M R) Abstract :The word "hijra" is an Urdu-Hindustani right to constitutional remedies for the protection of word derived from the Semitic Arabic root hjr in its civil rights by means of writs such as habeas sense of "leaving one's tribe,"and has been corpus. Violation of these rights result in borrowed into Hindi. The Indian usage has punishments as prescribed in the Indian Penal Code traditionally been translated into English as or other special laws, subject to discretion of the "eunuch" or "hermaphrodite," judiciary. The Fundamental Rights are defined as basic human freedoms that every Indian citizen has INTRODUCTION the right to enjoy for a proper and harmonious development of personality. These rights Human rights are rights inherent to all human universally apply to all citizens, irrespective of beings, regardless of gender, nationality, place of race, place of birth, religion, caste or gender. residency, sex, ethnicity, religion, color or and Aliens (persons who are not citizens) are also other categorization. Thus, human rights are non- considered in matters like equality before law. discriminatory, meaning that all human beings are They are enforceable by the courts, subject to entitled to them and cannot be excluded from them. certain restrictions Of course, while all human beings are entitled to human rights, not all human beings experience But till to date we don‘t recognize the transgender them equally throughout the world. -

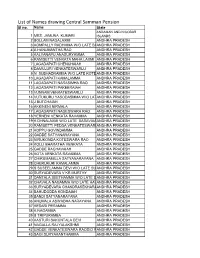

List of Names Drawing Central Samman Pension Sl No

List of Names drawing Central Samman Pension Sl no. Name State ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 MRS. JAMUNA KUMARI ISLANDS 2 BOLLAM NAGALAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 3 KOMPALLY RADHMMA W/O LATE BAANDHRA PRADESH 4 A HANUMANTHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 5 KALYANAPU ANASURYAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 6 RAMISETTI VENKATA MAHA LAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 7 LAGADAPATI CHENCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 8 DAMULURI VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 9 N SUBHADRAMMA W/O LATE KOTEANDHRA PRADESH 10 LAGADAPATI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 11 LAGADAPATI NARASIMHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 12 LAGADAPATI PAKEERAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 13 VUNNAM VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 14 VUTUKURU YASODASMMA W/O LATANDHRA PRADESH 15 J BUTCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 16 AKKINENI NIRMALA ANDHRA PRADESH 17 LAGADAPATI NAGESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 18 YERNENI VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 19 K DHNALAXMI W/O LATE BASAVAIAANDHRA PRADESH 20 RAMISETTI PEDDA VENKATESWARLANDHRA PRADESH 21 KOPPU GOVINDAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 22 GADDE SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 23 NIRUKONDA KOTESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 24 KOLLI BHARATHA VENKATA ANDHRA PRADESH 25 GADDE RAGHAVAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 26 KOTA VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 27 CHIRUMAMILLA SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 28 CHERUKURI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 29 S SUSEELAMMA DEVI W/O LATE SU ANDHRA PRADESH 30 SURYADEVARA V KR MURTHY ANDHRA PRADESH 31 DANTALA SEETHAMMA W/O LATE DANDHRA PRADESH 32 CHAVALA NAGAMMA W/O LATE HAVANDHRA PRADESH 33 SURYADEVARA CHANDRASEKHARAANDHRA PRADESH 34 BAHUDODDA KONDAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 35 BANDI SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 36 ANUMALA ASWADHA NARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 37 KESARI PERAMMA ANDHRA