329 Imagining Women's Social Space in Early Modern Keralam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farmer Database

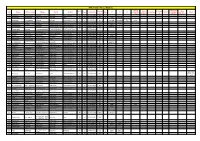

KVK, Trichy - Farmer Database Animal Biofertilier/v Gende Commun Value Mushroo Other S.No Name Fathers name Village Block District Age Contact No Area C1 C2 C3 Husbandry / Honey bee Fish/IFS ermi/organic Others r ity addition m Enterprise IFS farming 1 Subbaiyah Samigounden Kolakudi Thottiyam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 57 9787932248 BC 2 Manivannan Ekambaram Salaimedu, Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 58 9787935454 BC 4 Ixora coconut CLUSTERB 3 Duraisamy Venkatasamy Kolakudi Thottiam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787936175 BC Vegetable groundnut cotton EAN 4 Vairamoorthy Aynan Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 33 9787936969 bc jasmine ixora 5 subramanian natesan Sirupathur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787942777 BC Millet 6 Subramaniyan Thirupatur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787943055 BC Tapioca 7 Saravanadevi Murugan Keelakalkandarkottai THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI F 42 9787948480 SC 8 Natarajan Perumal Kattukottagai UPPILIYAPURAM TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 47 9787960188 BC Coleus 9 Jayanthi Kalimuthu top senkattupatti UPPILIYAPURAM Tiruchirappalli F 41 9787960472 ST 10 Selvam Arunachalam P.K.Agaram Pullampady TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 23 9787964012 MBC Onion 11 Dharmarajan Chellappan Peramangalam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 68 9787969108 BC sugarcane 12 Sabayarani Lusis prakash Chinthamani Musiri Tiruchirappalli F 49 9788043676 BC Alagiyamanavala 13 Venkataraman alankudimahajanam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 67 9788046811 BC sugarcane n 14 Vijayababu andhanallur andhanallur TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 30 9788055993 BC 15 Palanivel Thuvakudi THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 65 9788056444 -

2015-16 Term Loan

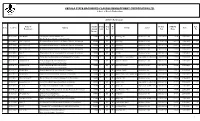

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Prisoner's Contact with Their Families

TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page No. List of Tables ii The Research Team iii Acknowledgments iv Glossary of Terms used in Prisons v Chapter I: Introduction 1 Chapter II: Review of Literature 5 Chapter III: Research Methodology 9 Chapter IV: Procedure and Practice for Prisoners’ Communication 14 with the Outside Chapter V: Communication Facilities: Processes, 35 Experiences and Perceptions Chapter VI: Good Practices and Recommendations 68 References 80 Appendix 81 End Notes 88 i List of Tables Title Page No. Table 3.1 Research Sites 10 Table 3.2. Number of Respondents (State-wise) 10 Table 4.1: Procedures for Prisoners’ Meetings with Visitors 14 Table 4.2. Facilities for Telephonic Communication 27 Table 4.3: Facilities for Communication through Inland-letters and Postcards 28 Table 4.4: Feedback and Concerns Shared about Practice and Procedure 29 ii The Research Team Researcher Ms. Subhadra Nair Data Collection Team Ms. Subhadra Nair Ms. Surekha Sale Ms. Pradnya Shinde Ms. Meenal Kolatkar Ms. Priyanka Kamble Ms. Karuna Sangare Ms. Komal Phadtare Report Writing Team Ms. Subhadra Nair Prof. Vijay Raghavan Dr. Sharon Menezes Ms. Devayani Tumma Ms. Krupa Shah Cover-page, Report Design and Layout Tabish Ahsan Administration Support Team Mr. Rajesh Gajbiye Ms. Shital Sakharkar Ms. Harshada Sawant Project Directors Prof. Vijay Raghavan Dr. Sharon Menezes iii Acknowledgements This study has reached its completion due to the support received from the Prison Departments of different states. We especially wish to thank the following persons for facilitating the study. 1. Shri S.N. Pandey, Director General (Prisons & Correctional Services), Mumbai, Maharashtra. 2. -

Kadamattathachan (1966 Film)

Kadamattathachan (1966 film) Kadamattathachan is a 1966 Indian Malayalam film, directed by KR Nambiar and produced by Rt Rev Fr George Thariyan. The film stars Sukumari, Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair, Anujan Kurichi and Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai in lead roles. The film had musical score by V. Dakshinamoorthy.[1][2][3]. Kadamattathachan is a 1984 Indian Malayalam film, directed and produced by NP Suresh. The film stars Prem Nazir, Srividya, Hari and Prathapachandran in lead roles. The film had musical score by A. T. Ummer and Traditional. Prem Nazir as Fr.Paulose/Kadamattathu Kathanar. Srividya as Kaliyankattu Neeli. Hari as Kunchavan Potti. Prathapachandran as Valiachan. K. P. A. C. Azeez as Kattummooppan. Bobby Kottarakkara as Thirumeni's Karyasthan. C. I. Paul as Pathrose. Janardanan as Aliyar. Starring: Sukumari, Thikkurissy Sukumaran Nair, Prem Nazir and others. Kadamattathachan is a 1966 Indian Malayalam film, directed by KR Nambiar and produced by Rt Rev Fr George Thariyan. The film stars Sukumari, Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair, Anujan Kurichi and Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai in lead roles. The film had musical score by V. Dakshinamoorthy. Kadamattathachan is a 1966 Indian Malayalam film, directed by KR Nambiar and produced by George Thariyan. The film stars Sukumari, Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair, Anujan Kurichi and Muthukulam Raghavan Pillai in lead roles. The film had musical score by V. Dakshinamoorthy.[1][2][3]. For faster navigation, this Iframe is preloading the Wikiwand page for Kadamattathachan (1966 film). Home. News. National & Gulf Center for Evidence Based Health Practice When We Were Lions 12 Golden Ducks Gayle, North Yorkshire Maisha Film Lab Andrew Scott (judge) Start Here https://t.co/FV56fzFdla https://www.facebook.com/Kadamattathachan-1966-film https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/Kadamattathachan-1966-film/id460373590 https://www.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2F.... -

1 SL NO. GL NO. NAME of the MEMBER Admitted on 1 1 Shri

LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED, SCHEME - 1 SL NO. GL NO. NAME OF THE MEMBER Admitted on 1 1 Shri. G.V. Narayana 05-06-1970 2 2 Dr. D. Janardhana Rao 05-06-1970 3 3 Shri. N. Sreehari Rao 05-06-1970 4 4 Smt. D. Bangaramma 05-06-1970 5 5 Shri. N. Saradhi Naidu 05-06-1970 6 6 Shri. K.V. Harinath 05-06-1970 7 7 Shri. P. Venkata Rao 05-06-1970 8 8 Shri. M. Narayana Rao 05-06-1970 9 9 Shri. B. Subrahmanyam 05-06-1970 10 10 Shri. M. Narayana Rao 05-06-1970 11 12 Smt. V. Ramalakshmi 05-06-1970 12 13 Shri. L. Yellaiah Naidu 05-06-1970 13 14 Shri. P.V. Jagannadham 05-06-1970 14 15 Shri. P. Sreenivas 05-06-1970 15 16 Shri. K.A. Jagannadham 05-06-1970 16 17 Shri. (L) Appalanarasayya 05-06-1970 17 18 Shri. (L) Veeraraju 05-06-1970 18 19 Shri. M. Vasudeva Rao 05-06-1970 19 20 Shri. V.B.V.S. Nageswara Rao 05-06-1970 20 21 J. Venkateswara Rao Naidu 05-06-1970 21 22 Shri. M. Venkata Rao Dora 30-03-1971 22 23 Shri. V. Venkata Krishna Rao 30-03-1971 23 24 D. Surya Atchtha Rama Raju 30-03-1971 24 25 Shri. P. Suryanarayana Raju 30-03-1971 25 26 Shri. D. Satyanarayana Rao 30-03-1971 26 27 Shri. V. Seetharama Murthy 30-03-1971 27 28 Shri. V. Satyanarayana Murthy 30-03-1971 28 29 Durga Venkata Rama Raju 30-03-1971 29 30 Smt. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 26.07.2020To01.08.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 26.07.2020to01.08.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr No - 1402 / Amal, age 19, S/o 2020U/s Balakrishnan, 01-08- 269,188 IPC SI SV BIJU BALAKRIS 19 CHERIYANA CHENGAN BAILED BY 1 AMAL Ambadiyil, 2020 & 4(2)(j)r/w CHENGANN HNAN Male DU NUR POLICE Cheriyanadu, 21:01 5 of KEDO UR PS 7907688599 2020, 118(E) of KP act. Cr No - 925 / 2020U/s 269,188 Ipc, 118(e) of Nikarthil house 01-08- kpAct, 32 KUTHIATH SI G BAILED BY 2 ANSAR KHADER Kuthiyathode P/w- Chavadi 2020 4(2)(j), 5, 6 Male ODE Remashan POLICE 2 Kuthiyathode 21:00 of kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No - 824 / 2020U/s Cherithekkathil 01-08- 4(2)(j),5 of 34 KURATHIK BAILED BY 3 Rajesh Chandran House Chunakara Chunakkara 2020 Kerala V Biju Male ADU POLICE east Chunakara 20:50 Epidemic Diseases Order 2020 Cr No - 924 / 2020U/s 269,188 Ipc, 118(e) of Vadakke veettil 01-08- kpAct, MUHAMME 32 Chavadi KUTHIATH SI G BAILED BY 4 ANWAR Kuthiyathode p/w- 2020 4(2)(j), 5, 6 D ASIF Male junction ODE Remashan POLICE 2 Kuthiyathode 20:45 of kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No - 1729 / 2020U/s 188, 269 IPC, 5 r/w CHALUVELI 01-08- 4(2)(j) of ABHILASH, 19 CHENGAND CHERTAL BAILED BY 5 ANANTHU DHANESH MUHAMMA P.O 2020 Kerala JR.SI OF Male A A POLICE MUHAMMA P/W-4 20:40 Epidemic POLICE Disease Ordinance 2020 & 118(e) of KP Act Cr No - Jaison, age 23yrs, 1401 / S/o Thomas 2020U/s Joseph, Manalel, 01-08- 269,188 IPC SI SV BIJU THOMAS 23 CHENGAN BAILED BY 6 JAISON Chirayilppadi, PERISSERY 2020 & 4(2)(j)r/w CHENGANN JOSEPH Male NUR POLICE Thittamel, 20:31 5 of KEDO UR PS Puliyoor, 2020, 8086881180 118(E) of KP act. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

MA English Revised (2016 Admission)

KANNUR Li N I \/EttSIl Y (Abstract) M A Programme in English Language programnre & Lirerature undcr Credit Based semester s!.stem in affiliated colieges Revised pattern Scheme. s,'rabus and of euestion papers -rmplemenred rvith effect from 2016 admission- Orders issued. ACADEMIC C SECTION UO.No.Acad Ci. til4t 20tl Civil Srarion P.O, Dared,l5 -07-20t6. Read : l. U.O.No.Acad/Ct/ u 2. U.C of €ven No dated 20.1O.2074 3. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pc) held on 06_05_2016. 4. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pG) held on 17_06_2016. 5. Letter dated 27.06.201-6 from the Chairman, Board of Studies in English(pc) ORDER I. The Regulations lor p.G programmes under Credit Based Semester Systeln were implernented in the University with eriect from 20r4 admission vide paper read (r) above dated 1203 2014 & certain modifications were effected ro rhe same dated 05.12.2015 & 22.02.2016 respectively. 2. As per paper read (2) above, rhe Scherne Sylrabus patern - & ofquesrion papers rbr 1,r A Programme in English Language and Literature uncler Credir Based Semester System in affiliated Colleges were implcmented in the University u,.e.i 2014 admission. 3. The meeting of the Board of Studies in En8lish(pc) held on 06-05_2016 , as per paper read (3) above, decided to revise the sylrabus programme for M A in Engrish Language and Literature rve'f 2016 admission & as per paper read (4) above the tsoard of Studies finarized and recommended the scheme, sy abus and pattem of question papers ror M A programme in Engrish Language and riterature for imprementation wirh efl'ect from 20r6 admissiorr. -

List of Books 2018 for the Publishers.Xlsx

LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE K.G. 1 Abkari Laws in Kerala Rajamohan/Ar latest 898 5 4490 avind Menon Govt. 2 Account Code I Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Govt. 3 Account Code II Kerala latest 160 10 1600 Publication Suvarna 4 Advocates Act latest 790 1 790 Publication Advocate's Welfare Fund Act George 5 & Rules a/w Advocate's Fees latest 120 3 360 Johnson Rules-Kerala Arbitration and Conciliation 6 Rules (if amendment of 2016 LBC latest 80 5 400 incorporated) Bhoo Niyamangal Adv. P. 7 latest 1500 1 1500 (malayalam)-Kerala Sanjayan 2nd 8 Biodiversity Laws & Practice LBC 795 1 795 2016 9 Chit Funds-Law relating to LBC 2017 295 3 885 Chitty/Kuri in Kerala-Laws 10 N Y Venkit 2012 160 1 160 on Christian laws in Kerala Santhosh 11 2007 520 1 520 Manual of Kumar S Civil & Criminal Laws in 12 LBC 2011 250 1 250 Practice-A Bunch of Civil Courts, Gram Swamy Law 13 Nyayalayas & Evening 2017 90 2 180 House Courts -Law relating to Civil Courts, Grama George 14 Nyayalaya & Evening latest 130 3 390 Johnson Courts-Law relating to 1 LIST I LIST OF STATE BARE ACTS TOTAL STATE BARE ACTS 2018 PRICE (in EDITION SL.No. Rupees) COPIES AUTHOR/ REQUIRED PRICE FOR EDN / YEAR PUBLISHER EACH COPY APPROXIMATE Civil Drafting and Pleadings 15 With Model / Sample Forms LBC 2016 660 1 660 (6th Edn. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78.