Poovar Village of Thiruvananthapuram District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Covid 19 Coastal Plan- Trivandrum

COVID-19 -COASTAL PLAN Management of COVID-19 in Coastal Zones of Trivandrum Department of Health and Family Welfare Government of Kerala July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS THIRUVANANTHAPURAMBASIC FACTS .................................. 3 COVID-19 – WHERE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM STANDS (AS ON 16TH JULY 2020) ........................................................ 4 Ward-Wise maps ................................................................... 5 INTERVENTION PLANZONAL STRATEGIES ............................. 7 ANNEXURE 1HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE - GOVT ................. 20 ANNEXURE 2HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE – PRIVATE ........... 26 ANNEXURE 3CFLTC DETAILS................................................ 31 ANNEXURE 4HEALTH POSTS – COVID AND NON-COVID MANAGEMENT ...................................................................... 31 ANNEXURE 5MATERIAL AND SUPPLIES ............................... 47 ANNEXURE 6HR MANAGEMENT ............................................ 50 ANNEXURE 7EXPERT HEALTH TEAM VISIT .......................... 56 ANNEXURE 8HEALTH DIRECTORY ........................................ 58 2 I. THIRUVANANTHAPURAM BASIC FACTS Thiruvananthapuram, formerly Trivandrum, is the capital of Kerala, located on the west coastline of India along the Arabian Sea. It is the most populous city in India with the population of 957,730 as of 2011.Thiruvananthapuram was named the best Kerala city to live in, by a field survey conducted by The Times of India.Thiruvananthapuram is a major tourist centre, known for the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, the beaches of -

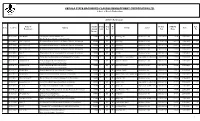

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram Rural District from 22.03.2015 to 28.03.2015

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram Rural district from 22.03.2015 to 28.03.2015 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Manappalli Cr.443/15 U/s Veedu,Altharamoodu, D.Unnikrishnan, JFMC 1 1 Suresh Madaswami 43.M Attingal 24/03/15 294(b),447,323 Attingal Darsanavattom,Nagar SCPO 9959 Attingal ,324,34 IPC oor Manappalli Cr.443/15 U/s Veedu,Altharamoodu, D.Unnikrishnan, JFMC 1 2 Leena Radha 37.F Attingal 24/03/15 294(b),447,323 Attingal Darsanavattom,Nagar SCPO 9959 Attingal ,324,34 IPC oor Manappalli Cr.443/15 U/s Veedu,Altharamoodu, D.Unnikrishnan, JFMC 1 3 Laila Kamala 51.F Attingal 24/03/15 294(b),447,323 Attingal Darsanavattom,Nagar SCPO 9959 Attingal ,324,34 IPC oor SAR Cr.480/15 U/s Manzil,Alamcode,The 25.03.2015, 118(i) of KP Act JFMC 1 4 Sharafudeen Abdul Rasaq 42.M Alamcode Attingal B.Jayan,SI ncherykonam,Manam 17.30 Hrs & 6(b) of Attingal boor COTPA Cr.508/15 Charuvila U/s118 Iof JS Praveen SI of 5 Sudharmani Parvathi 50 veedu,Nr.THQ Nr,.Govt HS 24-03-2015 Varkala JFMC I Varkala KPAct sec6 r/w Police Hospital,Varkala 24 of COTPA Cr.397/15 U/s.20 (b) (i)of M.Sukumar,Add Kunnil 23-03- Narcotic Drugs l.SI of JFMC 1 6 ChandraBose Vasu 66,m veedu,Mavinmoodu,O Mullaramcodu Kallambalam 15,15.00Hrs and Police,Kallambal Varkakala ttoor psychotropic am substance act Suji nivas, (CP/VIII)Nr.Guru G. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 26.07.2020To01.08.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 26.07.2020to01.08.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr No - 1402 / Amal, age 19, S/o 2020U/s Balakrishnan, 01-08- 269,188 IPC SI SV BIJU BALAKRIS 19 CHERIYANA CHENGAN BAILED BY 1 AMAL Ambadiyil, 2020 & 4(2)(j)r/w CHENGANN HNAN Male DU NUR POLICE Cheriyanadu, 21:01 5 of KEDO UR PS 7907688599 2020, 118(E) of KP act. Cr No - 925 / 2020U/s 269,188 Ipc, 118(e) of Nikarthil house 01-08- kpAct, 32 KUTHIATH SI G BAILED BY 2 ANSAR KHADER Kuthiyathode P/w- Chavadi 2020 4(2)(j), 5, 6 Male ODE Remashan POLICE 2 Kuthiyathode 21:00 of kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No - 824 / 2020U/s Cherithekkathil 01-08- 4(2)(j),5 of 34 KURATHIK BAILED BY 3 Rajesh Chandran House Chunakara Chunakkara 2020 Kerala V Biju Male ADU POLICE east Chunakara 20:50 Epidemic Diseases Order 2020 Cr No - 924 / 2020U/s 269,188 Ipc, 118(e) of Vadakke veettil 01-08- kpAct, MUHAMME 32 Chavadi KUTHIATH SI G BAILED BY 4 ANWAR Kuthiyathode p/w- 2020 4(2)(j), 5, 6 D ASIF Male junction ODE Remashan POLICE 2 Kuthiyathode 20:45 of kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No - 1729 / 2020U/s 188, 269 IPC, 5 r/w CHALUVELI 01-08- 4(2)(j) of ABHILASH, 19 CHENGAND CHERTAL BAILED BY 5 ANANTHU DHANESH MUHAMMA P.O 2020 Kerala JR.SI OF Male A A POLICE MUHAMMA P/W-4 20:40 Epidemic POLICE Disease Ordinance 2020 & 118(e) of KP Act Cr No - Jaison, age 23yrs, 1401 / S/o Thomas 2020U/s Joseph, Manalel, 01-08- 269,188 IPC SI SV BIJU THOMAS 23 CHENGAN BAILED BY 6 JAISON Chirayilppadi, PERISSERY 2020 & 4(2)(j)r/w CHENGANN JOSEPH Male NUR POLICE Thittamel, 20:31 5 of KEDO UR PS Puliyoor, 2020, 8086881180 118(E) of KP act. -

Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum

LATIN ARCHDIOCESE OF TRIVANDRUM His Grace, Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 11.03.1946 Date of Ordination : 20.12.1969 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 02.02.1990 Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum: 17.06.2004 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org 1 His Excellency, Most Rev. Dr. Christudas Rajappan Auxiliary Bishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 25.11.1971 Date of Ordination : 25.11.1998 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 03.04.2016 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 Mobile : 8281012253, 8714238874, E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org (Dates below the address are Dates of Birth (B) and Ordination (O)) 2 1. Very Rev. Msgr. Dr. C. Joseph, B.D., D.C.L. Vicar General & Chancellor PRO & Spokesperson Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003, Kerala, India T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001; Mobile: 9868100304 Email: [email protected], [email protected] B: 14.04.1949 / O: 22.12.1973 2. Very Rev. Fr. Jose G., MCL Judicial Vicar, Metropolitan Archdiocesan Tribunal & Chairman, Archdiocesan Arbitration and Conciliation Forum Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001 & Parish Priest, St. Theresa of Lisieux Church, Archbishop's House Compound, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003 T: 0471-2314060 , Office ; 0471-2315060 ; C: 0471- 2316734 Web: www.vellayambalamparish.org Mobile: 9446747887 Email: [email protected] B: 06.06.1969 / O: 07.01.1998 3. -

Notice Inviting Quotations-E.E Mavelikkara Division 12/03/2019,3Pm

TRAVANCORE DEVASWOM BOARD NOTICE INVITING QUOTATIONS EEM/Q/18-19 /No. 10 Competitive and sealed quotations are invited from the registered contractors of Travancore Devaswom Board for the following works so as to reach the office of the undersigned on or before 12/03/2019 at 3 pm. The quotations will be opened on the same day at 3.30 PM Sl. Qtn. No. Name of work EMD Cost of Time of No schedule completi . on 1 Q-142/18-19 Ambalappuzha devaswom- Ambalappuzha 2350/- 500+GST 15 days group- Annual maintenanace to temple structure and Oottupura in connection with festival in 1194ME PAC: 92,181/- 2 Q-143/18-19 Ambalappuzha Devaswom in 1550/- 300+GST 1 month Ambalappuzha group- urgent repairs and maintenance works to the campshed building PAC: 61,314/- 3 Q-144/18-19 Ambalappuzha Devaswom –Ambalappuzha 2000/- 500+GST 15 days group- Putting up pandal (convention pandal) in connection with festival in 1194ME PAC: 76,294/- 4 Q-145/18-19 Kalarkode devaswom Ambalappuzha 1750/- 500+GST 1 month group- Repairs and maintenance to the toilet block reg PAC: 69,642/- 5 Q-146/18-19 Kalarcode Devaswom – Ambalappuzha 2450/- 500+GST 1 month group- Repairs to the Kulikkadavu of temple pond reg PAC: 96,237/- 6 Q-147/18-19 Kalarcode Devaswom – Ambalappuzha 2050/- 500+GST 1 month group- Interlocking around the temple well and some other urgent works PAC: 80,498/- 7 Q-148/18-19 Kalarcode devaswom – Ambalappuzha 600/- 300+GST 15 days group- painting to the Ganapathy shrine- reg PAC: 21,916/- 8 Q-149/18-19 Kalarcode Devaswom- Ambalappuzha 2050/- 500+GST 1 month group- -

Destinations - Total - 79 Nos

Department of Tourism - Project Green Grass - District-wise Tourist Destinations - Total - 79 Nos. Sl No. Sl No. (per (Total 79) District District) Destinations Tourist Areas & Facilities LOCAL SELF GOVERNMENT AUTHORITY 1 TVM 01 KANAKAKKUNNU FULL COMPOUND THIRUVANANTHAPURAM CORPORATION 2 02 VELI TOURIST VILLAGE FULL COMPOUND THIRUVANANTHAPURAM CORPORATION AKKULAM TOURIST VILLAGE & BOAT CLUB & THIRUVANANTHAPURAM CORPORATION, 3 03 AKKULAM KIRAN AIRCRAFT DISPLAY AREA PONGUMMUDU ZONE GUEST HOUSE, LIGHT HOUSE BEACH, HAWAH 4 04 KOVALAM TVM CORPORATION, VIZHINJAM ZONE BEACH, & SAMUDRA BEACH 5 05 POOVAR POOVAR BEACH POOVAR G/P SHANGUMUKHAM BEACH, CHACHA NEHRU THIRUVANANTHAPURAM CORPORATION, FORT 6 06 SANGHUMUKHAM PARK & TSUNAMI PARK ZONE 7 07 VARKALA VARKALA BEACH & HELIPAD VARKALA MUNICIPALITY 8 08 KAPPIL BACKWATERS KAPPIL BOAT CLUB EDAVA G/P 9 09 NEYYAR DAM IRRIGATION DEPT KALLIKKADU G/P DAM UNDER IRRGN. CHILDRENS PARK & 10 10 ARUVIKKARA ARUVIKKARA G/P CAFETERIA PONMUDI GUEST HOUSE, LOWER SANITORIUM, 11 11 PONMUDI VAMANAPURAM G/P UPPER SANITORIUM, GUEST HOUSE, MAITHANAM, CHILDRENS PARK, 12 KLM 01 ASHRAMAM HERITAGE AREA KOLLAM CORPORATION AND ADVENTURE PARK 13 02 PALARUVI ARAYANKAVU G/P 14 03 THENMALA TEPS UNDERTAKING THENMALA G/P 15 04 KOLLAM BEACH OPEN BEACH KOLLAM CORPORATION UNDER DTPC CONTROL - TERMINAL ASHTAMUDI (HOUSE BOAT 16 05 PROMENADE - 1 TERMINAL, AND OTHERS BY KOLLAM CORPORATION TERMINAL) WATER TRANSPORT DEPT. 17 06 JADAYUPARA EARTH CENTRE GURUCHANDRIKA CHANDAYAMANGALAM G/P 18 07 MUNROE ISLAND OPEN ISLAND AREA MUNROE THURUTH G/P OPEN BEACH WITH WALK WAY & GALLERY 19 08 AZHEEKAL BEACH ALAPPAD G/P PORTION 400 M LENGTH 20 09 THIRUMULLAVAROM BEACH OPEN BEACH KOLLAM CORPORATION Doc. Printed on 10/18/2019 DEPT OF TOURISM 1 OF 4 3:39 PM Department of Tourism - Project Green Grass - District-wise Tourist Destinations - Total - 79 Nos. -

Final Report Vizhinjam Sia English 31.12.20

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY Final Report Entrusted by Revenue (B) Department, Kerala Government, Thiruvananthapuram LAND ACQUISITION FOR THE VIZHINJAM INTERNATIONAL SEAPORT PROJECT IN VIZHINJAM AND KOTTUKAL VILLAGES IN THIRUVANATHAPURAM DISTRICT 17.12.2020 Requiring Body SIA Unit Vizhinjam International RajagirioutREACH Seaport Ltd Rajagiri College of Social 9th Floor, KSRTC Bus Sciences Terminal Complex Rajagiri.P.O.,Kalamassery Thampanoor Pin: 683104 Thiruvananthapuram Ph:0484 – 2911330-32, Pin: 695001 2550-785 [email protected] www.rajagirioutreach.in CONTENTS Chapter 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Project and public purpose 1.2 Location 1.3 Size and attributes of land acquisition 1.4 Alternatives considered 1.5 Social impacts 1.6 Mitigation measures Chapter 2 Detailed Project Descriptions 2.1 Background of the project, including developer’s background and governance/ management structure 2.2 Rationale for project including how the project fits the public purpose criteria listed in the Act 2.3 Details of project size, location, capacity, outputs, production targets, costs and risks 2.4 Examination of alternatives 2.5 Phases of the project construction 2.6 Core design features and size and type of facilities 2.7 Need for ancillary infrastructural facilities 2.8 Work force requirements (temporary and permanent) 2.9 Details of social impact assessment/ environment impact assessment if already conducted and any technical feasibility reports 2.10 Applicable legislations and policies 2 Land acquisition for the Vizhinjam International seaport -

Sl. No. District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban No of Members Initiative LUNCH Parcel by Unit

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Sl. No Of Parcel Home Sponsored District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban Initiative Contact No No. Members By Unit Delivery by LSGI's (May 24) (May 24) (May 24) 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 148 0 9544149437 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Coir Machine Manufacturing Company Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 0 3323 87 8606334340 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Community kitchen thavakkal group MCH junction Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 205 352 6238772189 4 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 130 500 9745746427 5 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 0 92 78 9656113003 6 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha North Annam janakeeya bhakshanashala Vandanam Rural 7 Janakeeya Hotel 0 42 73 919656146204 7 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 342 6 9061444582 8 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 0 499 0 9961423245 9 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Poompatta catering and Bakery Unit Valiya azheekal, Aratpuzha Rural 3 Janakeeya Hotel 0 155 0 9544122586 10 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 48 0 8921361281 11 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 33 0 587 9562320377 12 Alappuzha Aryad Anagha Catering Near Aryad Panchayat Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 435 0 9562345109 13 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal -

Directorate of Health Services List of Modern Medicine Institutions

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DIRECTORATE OF HEALTH SERVICES LIST OF MODERN MEDICINE INSTITUTIONS 2016-17 PREPARED BY HEALTH INFORMATION CELL OFFICIALS Usha Kumari.S Additional Director (FW) Suresh Kumar.N Demographer Prabhakumari.P Chief Statistician Sasi.R Statistical Assistant Nisha. A.K Statistical Assistant Grade I Mahesh.G Statistical Assistant Grade II PREFACE The present publication titled "List of Modern Medicine Institutions under Directorate of Health Services 2016-17" provides basic Statistics about the institutions under Directorate of Health Services, Kerala. This data base will be guiding factor for the planning of health related activities under Government of Kerala. This can be good source of reference to the research scholars in the field of health and other sectors. I congratulate the staff of Health Information Cell and District Statistics Wing for their efforts in compiling these data from various primary as well as secondary sources. Thiruvananthapuram Dr.Saritha.R.L Date: 29-08-2017 Director of Health Services 1 INDEX Chapter No. Subject/Particulars Page No. 1 Preface 1 2 Index 2 3 General Hospitals 3-4 4 District Hospitals 5-6 5 W & C Hospital 7 6 Mental Health Centre, TB Hospital 8 7 Leprosy Hospital, Speciality Others 9 8 District TB Centre 10-11 9 Taluk Head Qurters Hospital 12-15 10 Taluk Hospital 16-19 11 Community Health Centre 20-41 12 (24X7) Primary Health Centre 42-55 13 Primary Health Centre 56-111 14 Mobile Units/Dispensaries 112-118 15 Abstract of Health Institutions 119 16 Bed Strength( Rural & Urban) 120-127 2 GENERAL HOSPITALS Sancti Name of the Corp/ (C/ Name of Sl.