Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra

Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Anupama Chopra 2000 #Anupama Chopra #014029970X, 9780140299700 #Sholay, the Making of a Classic #Penguin Books India, 2000 #National Award Winner: 'Best Book On Film' Year 2000 Film Journalist Anupama Chopra Tells The Fascinating Story Of How A Four-Line Idea Grew To Become The Greatest Blockbuster Of Indian Cinema. Starting With The Tricky Process Of Casting, Moving On To The Actual Filming Over Two Years In A Barren, Rocky Landscape, And Finally The First Weeks After The Film'S Release When The Audience Stayed Away And The Trade Declared It A Flop, This Is A Story As Dramatic And Entertaining As Sholay Itself. With The Skill Of A Consummate Storyteller, Anupama Chopra Describes Amitabh Bachchan'S Struggle To Convince The Sippys To Choose Him, An Actor With Ten Flops Behind Him, Over The Flamboyant Shatrughan Sinha; The Last-Minute Confusion Over Dates That Led To Danny Dengzongpa'S Exit From The Fim, Handing The Role Of Gabbar Singh To Amjad Khan; And The Budding Romance Between Hema Malini And Dharmendra During The Shooting That Made The Spot Boys Some Extra Money And Almost Killed Amitabh. file download natuv.pdf UOM:39015042150550 #Dinesh Raheja, Jitendra Kothari #The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema #Motion picture actors and actresses #143 pages #About the Book : - The Hundred Luminaries of Hindi Cinema is a unique compendium if biographical profiles of the film world's most significant actors, filmmakers, music #1996 the Performing Arts #Jvd Akhtar, Nasreen Munni Kabir #Talking Films #Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar #This book features the well-known screenplay writer, lyricist and poet Javed Akhtar in conversation with Nasreen Kabir on his work in Hindi cinema, his life and his poetry. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Why Shakespeare? Dennis Kennedy and Yong Li Lan

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51552-8 - Shakespeare in Asia: Contemporary Performance Edited by Dennis Kennedy and Yong Li Lan Excerpt More information chapter 1 Introduction: Why Shakespeare? Dennis Kennedy and Yong Li Lan This book treats contemporary Shakespeare performance in Asia from theoretical and historical perspectives: it is interested in how and why Shakespeare operates on the stage, in film, and in other performative modes in regions of the world that have no overwhelming reason to turn to him. The essayists represented here offer questions about cultural difference and cultural value, appropriation and dissemination, corporeal and intellectual adaptation, and the ways in which Asia is part of and simultaneously stands aloof from global civilization. Much has happened on planet Shakespeare since 1990. For our purposes the most important development has been a notable increase in Shakespeare performance in surroundings alien to the traditions of the main English-speaking nations, some of which has been exported to the West, prompting corresponding expansion in the international critical attention those productions have received in the popular press and in the academy. The collapse of the former Soviet empire and its satellite states, a major increase in globalized communications and marketing, political and economic migration, busi- ness and touristic travel, and the internationalizing of stock exchanges, among other issues, have combined to make many parts of the world aware of cultural products previously unknown or undervalued, or prompted re-evaluations of work already known. Some of this has been connected to the result of the globalizing of American movies and television, but it has affected Shakespeare as well. -

Dossier-De-Presse-L-Ombrelle-Bleue

Splendor Films présente Synopsis Dans un petit village situé dans les montagnes de l’Himalaya, une jeune fille, Biniya, accepte d’échanger son porte bonheur contre une magnifique ombrelle bleue d’une touriste japonaise. Ne quittant plus l’ombrelle, l’objet L’Ombrelle semble lui porter bonheur, et attire les convoitises des villageois, en particulier celles de Nandu, le restaurateur du village, pingre et coléreux. Il veut à tout prix la récupérer, mais un jour, l’ombrelle disparaît, et Biniya bleue mène son enquête... Note de production un film de Vishal Bhardwaj L’Ombrelle bleue est une adaptation cinématographique très fidèle à la nouvelle éponyme de Ruskin Bond. Le film a été tourné dans la région de l’Himachal Pradesh, située au nord de l’Inde, à la frontière de la Chine et Inde – 2005 – 94 min – VOSTFR du Pakistan, dans une région montagneuse. La chaîne de l’Himalaya est d’ailleurs le décor principal du film, le village est situé à flanc de montagne. Inédit en France L’Ombrelle bleue reprend certains codes et conventions des films de Bollywood. C’est pourtant un film original dans le traitement de l’histoire. Alors que la plupart des films de Bollywood durent près de trois heures et traitent pour la plupart d’histoires sentimentales compliquées par la religion et les obligations familiales, L’Ombrelle bleue s’intéresse davantage aux caractères de ses personnages et à la nature environnante. AU CINÉMA Le film, sorti en août 2007 en Inde, s’adresse aux enfants, et a pour LE 16 DÉCEMBRE vedettes Pankaj Kapur et Shreya Sharma. -

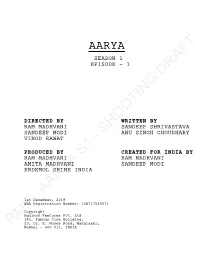

Aarya S1 Ep1.5 Shooting Draft 22Nd

AARYA SEASON 1 EPISODE - 1 DIRECTED BY WRITTEN BY RAM MADHVANI SANDEEP SHRIVASTAVA SANDEEP MODI ANU SINGH CHOUDHARY VINOD RAWAT PRODUCED BY CREATED FOR INDIA BY RAM MADHVANI RAM MADHVANI AMITA MADHVANI SANDEEP MODI ENDEMOL SHINE INDIA 1st December, 2019 SWA Registration Number: 108717539571 Copyright Equinox Features Pvt. Ltd 140, Famous Cine Building, 20, Dr. E. Moses Road, Mahalaxmi, RMFMumbai - - AARYA400 011, INDIA S1 - SHOOTING DRAFT FADE IN: 0A/0AA 0A/0AA TITLE SEQUENCE 1.1 EXT. POPPY FIELDS/ROAD. DAY. 1.1 **OMITTED** 1.2/2A INT. AARYA’S HOUSE. GYM/LIVING ROOM. DAY. 1.2/2ADRAFT We introduce a 40-year old, tall, fit and athletic woman, in her yoga pants upside down hanging on her training rings. A cleaning robot comes and cleans the area around her. Her phone is buzzing on vibrate. Her concentration is being challenged. There is the morning pandemonium. Outside we can hear clanking of utensils and squabble of two boys. VEER ADITYA Bag de. I want to check it Mere paas nahin hai, Bhaiya. myself. Mamma! She turns upside down and goes straight, takes a breath and dives deep into the routine crisis management of the home as she steps into the living room.SHOOTING She is AARYA. The house is modern and luxurious.- A maid, Poonam is overlooking packing the tiffins, a cook whips up the breakfast. She answers the call, it is from Soundarya. S1AARYA Hi Chotti. Aaj jaldi uthi hai yah kal raat bhar soyi nahin? SOUNDARYA (O.S) Didi, meri taang baad mein kheenchna. Hum pahle jeweler ko mil lein? Meanwhile,AARYA In the family den, Aarya’s two sons VEER (16) and ADITYA (8) are jostling in the living room. -

Psychoanalysis of Female Characters in Vishal Bharadwaj's Trilogy

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Psychoanalysis of Female Characters in Vishal Bharadwaj’s Trilogy Maqbool, Omkara and Haider Shikha Rani, Research Scholar MJP Rohilkhand University Bareilly Alka Mehra Assistant Professor Government Degree College Bisalpur MJP Rohilkhand University Bareilly Abstract: Freud’s theory of psychology that he referred as psychoanalysis has been accepted and extended in analyzing literature and other arts too. Freud believes that literature and other arts are like dreams and psycho symptoms which contain imaginative fancies, so literature and other arts are capable to fulfill wishes that are commonly restricted by social standards and norms. My research paper is an attempt to focus on the psychoanalysis of female protagonists in Bharadwaj’s worldwide acclaimed movies ‘Maqbool’, ‘Omkara’ and ‘Haider’ which are an adaptation of Shakespeare’s famous tragedies ‘Macbeth’, ‘Othello’ and ‘Hamlet’. These female characters are just like puppet in grip of unconscious urges. This study further analysis human’s helplessness under the arrest of its uncontrolled passions. Through this study, I want to find out the strong and weak unconscious fancies of Nimmi, Dolly and Gazala and their fight against their own id, ego and superego which brutally influenced them mentally as well as physically. Nimmi who is a complex character, struggles as a mistress of don and as a beloved of Maqbool. Dolly suffers mentally due to male’s suspicious nature and patriarchal society whereas Gazala tries to make conciliation with her second marriage and with her adult obsessive son. Keyword: psychoanalysis, sex complex obsessive, conflict. Shakespeare’s plays have been adapted all over the world due to his universality and cosmopolitan nature. -

Trends in Organized Crimes

International Journal of Law and Legal Jurisprudence Studies :ISSN:2348-8212:Volume 3 Issue 4 154 TRENDS IN ORGANIZED CRIMES Manik Sethi and Smeeksha Pandey1 Abstract There is wide support for the argument and assertion that organized crime has increased in the last decade. But the problem for any discussion on organized crime is establishing the extent to which it exists and the size of the threat to democracy and security that it could represent. The myth, mystery and secrecy that surrounds organized crime and the clandestine nature with which it operates makes it hard to quantify and reach sound conclusions on. One of the most important factors is the establishing of a proper and sound working definition of organized crime in order to move away from the mythical notions that pervade the popular conscious and perhaps many security and intelligence institutions within India. Organized crime, it would seem, is extremely complex involving many different groups and people who operate in a variety of different ways and styles. Some it is equally important to establish the differences as well as the common features of organized crime. It is not possible to respond effectively to organized crime until it is fully understood. The goal of any organized criminal activity is to make huge profits that need to be laundered before the capital can be used to expand their illegal business empires. Rendering banking transparent at a business level would go some way to eradicating money laundering, ultimately impeding and inhibiting the expansion of organized crime, and arguably represents one of the key measures in its control. -

Adavi Nitin Movie Free 47

1 / 4 Adavi Nitin Movie Free 47 4) Apart of Tollywood movies he also worked as an actor in Bollywood movie “Agyaat”, which was released in 2009 and was dubbed into Telugu as 'Adavi'.. Watch Now: telugu jilebi movie hotadia jahan provaw xxx karishimax dog clip to all and girl sex ... Sona Hot leaked clip - malayalam actress- watchfull from telugu movie sex clip ... 20 min 47 sec, 67.5K Views ... in alone | telugu movie lesbian videos | telugu na peru surya movie | adavi telugu nithin movie 2009 | telugu movie .... Aranyamlo Latest Telugu Full Length Movie | 2017 Movies, Subscribe ... 0:00 / 1:58:47 ... Click here to Watch Renigunta Full Movie: https://goo.gl/oY55PH 2017 ... Adavi Lo Last Bus Telugu Full Movie | 2020 Latest Telugu Full .... Adavi Movie Online Watch Adavi Full Length HD Movie Online on YuppFlix. Adavi Film Directed by Ramesh G Cast Vinoth Krishnan,Ammu Abhirami.. Priyanka Kothari is playing heroine in Ramgopal Varma\'s 'Agyaat' (Hindi) and \'Adavi\' ( Telugu) opposite to Nithin.. Chatrapathi- ఛత్రపతి Telugu Full Movie || Prabhas || Shriya Saran || Bhanupriya || TVNXT. (2:39:30 min) ... (2:36:47 min) views ... Daring Tiger Nitin (Aatadista) Full Hindi Dubbed Movie | Nitin movies hindi dubbed, Kajal Agarwal. (2:2:31 min) ... Adavi Ramudu | Telugu Full Movie | NTR, Jayaprada, Jayasudha. (2:32:8 .... Rani Mukerji starrer Mardaani to be tax free in MP Get your ... The stunning actress turns 47 today. ... 'I enjoyed making Adavi Kachina Vennela' ... Nitin Kakkar's National award-winning film releases in Indian theatres tomorrow, June 6.. Find Nitin Varma's contact information, age, background check, white pages, criminal records, photos, .. -

Gangs of Wasseypur As an Active Archive of Popular Cinema

M A D H U J A M U K H E R J E E Of Recollection, Retelling, and Cinephilia: Reading Gangs of Wasseypur as an Active Archive of Popular Cinema This paper studies Gangs of Wasseypur (Parts 1 and 2, 2012) as a definitive text via which Anurag Kashyap’s style became particularly provocative and pointed. While a range of films (both directed and produced by Kashyap) seemingly bear a certain ‘Kashyap mark’ in the manner in which they tackle subjects of violence and belligerent speech with an unpredictable comic sense, I argue that, more importantly, these films work within a particular visual framework with regard to its mise-en- scène (including the play of light, camera movement, modes of performance), as well as produce recognisable plot structures (involving capricious and realistic events), settings and locations (like the city’s underbelly, police stations, etc.), and so on. Indeed, Kashyap has made a set of films—including Paanch (unreleased), No Smoking (2007) and Ugly (2014)—which deal with similar issues, and explore contemporary cityscapes, especially Mumbai, with fervidness, thereby commenting on urban dystopia.1 Furthermore, these films speak to what has been analysed as the ‘Bombay noir’ mode by Lalitha Gopalan, by means of thoughtful art and set design, engaging (and often hand-held) camera movements and swish-pans, uses of blue or yellow filters, character prototypes, and reflective performances, which generate a world that is engulfed by a deep sense of disquiet and distress. This paper draws attention to such stylistic explorations, especially JOURNAL OF THE MOVING IMAGE 91 to the ways in which it has developed through Kashyap’s recent films. -

Responses to 100 Best Acts Post-2009-10-11 (For Reference)

Bobbytalkscinema.Com Responses/ Comments on “100 Best Performances of Hindi Cinema” in the year 2009-10-11. submitted on 13 October 2009 bollywooddeewana bollywooddeewana.blogspot.com/ I can't help but feel you left out some important people, how about Manoj Kumar in Upkar or Shaheed (i haven't seen that) but he always made strong nationalistic movies rather than Sunny in Deol in Damini Meenakshi Sheshadri's performance in that film was great too, such a pity she didn't even earn a filmfare nomination for her performance, its said to be the reason on why she quit acting Also you left out Shammi Kappor (Junglee, Teesri MANZIL ETC), shammi oozed total energy and is one of my favourite actors from 60's bollywood Rati Agnihotri in Ek duuje ke Liye Mala Sinha in Aankhen Suchitra Sen in Aandhi Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi Ashok Kumar in Mahal Mumtaz in Khilona Reena Roy in Nagin/aasha Sharmila in Aradhana Rajendra Kuamr in Kanoon Time wouldn't permit me to list all the other memorable ones, which is why i can never make a list like this bobbysing submitted on 13 October 2009 Hi, As I mentioned in my post, you are right that I may have missed out many important acts. And yes, I admit that out of the many names mentioned, some of them surely deserve a place among the best. So I have made some changes in the list as per your valuable suggestion. Manoj Kumar in Shaheed (Now Inlcuded in the Main 100) Meenakshi Sheshadri in Damini (Now Included in the Main 100) Shammi Kapoor in Teesri Manzil (Now Included in the Main 100) Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sharmila Togore in Aradhana (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sunny Deol in Damini (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Mehmood in Pyar Kiye Ja (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Nagarjun in Shiva (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) I hope you will approve the changes made as per your suggestions. -

Indian Film Week Tydzień Kina Indyjskiego

TYDZIEń KINA INDYJSKIEGO 100-lecie kina w indiach kino kultura, warszawa 5–10 listopada 2012 INDIAN FILM WEEK 100 years of indian cinema kino kultura, warsaw 5–10 november 2012 W tym roku obchodzimy 100-lecie Kina Indyjskiego. This year we celebrate 100 years of Indian Cinema. Wraz z powstaniem pierwszego niemego filmu With the making of the first silent film ‘Raja Harish- „Raja Harishchandra” w 1913 roku, Indyjskie Kino chandra’ in 1913 , Indian Cinema embarked on an ex- wyruszyło w pasjonującą i malowniczą podróż, ilu- citing and colourful journey, reflecting a civilization strując przemianę narodu z kolonii w wolne, demokra- in transition from a colony to a free democratic re- tyczne państwo o bogatym dziedzictwie kulturowym public with a composite cultural heritage and plural- oraz wielorakich wartościach i wzorcach. istic ethos. Indyjska Kinematografia prezentuje szeroki Indian Cinema showcases a rich bouquet of lov- wachlarz postaci sympatycznych włóczęgów, ponad- able vagabonds, evergreen romantics, angry young czasowych romantyków, młodych buntowników, men, dancing queens and passionate social activists. roztańczonych królowych i żarliwych działaczy spo- Broadly defined by some as ‘cinema of interruption’, łecznych. Typowe Kino Indyjskie, zwane bollywoodz- complete with its song and dance ritual, thrills and ac- kim, przez niektórych określane szerokim mianem tion, melodrama, popular Indian cinema, ‘Bollywood’, „cinema of interruption” – kina przeplatanego pio- has endeared itself to global audiences for its enter- senką, tańcem, emocjami i akcją, teatralnością, dzięki tainment value. Aside from all the glitz and glamour walorowi rozrywkowemu, zjednało sobie widzów na of Bollywood, independent art house cinema has been całym świecie. Oprócz pełnego blichtru i przepy- a niche and has made a seminal contribution in en- chu Bollywood, niszowe niezależne kino artystyczne hancing the understanding of Indian society.