Modernism-Hizuchi.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism IC I ICOMOS COMOS O M OS

Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne Welterbevorschläge aus Mittel- und Osteuropa Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism World Heritage Proposals from Central and Eastern Europe Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne SocialistSocialist Modernism Realism and III V L S EE T MI O ALK N O I T A N N E CH S UT E D S ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES LVIII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LVIII ICOMOS · HEFTE DE ICOMOS ICOMOS · CAHIERS DU COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LVIII Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism I NTERNATIONAL COUNCIL on MONUMENTS and SITES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SITES CONSEJO INTERNACIONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SITIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne. Welterbevorschläge aus Mittel- und Osteuropa Dokumentation des europäischen Expertentreffens von ICOMOS über Möglichkeiten einer internationalen seriellen Nominierung von Denkmalen und Stätten des 20. Jahrhunderts in postsozialistischen Ländern für die Welterbeliste der UNESCO – Warschau, 14.–15. April 2013 – Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism. World Heritage Proposals from Central and Eastern Europe Documentation of the European expert meeting of ICOMOS on the feasibility of an international serial nomination of 20th century monuments and sites in post-socialist countries for the UNESCO World Heritage List – Warsaw, 14th–15th of April 2013 – ICOMOS · H E F T E des D E U T S CHEN N AT I ONAL KO MI T E E S LVIII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LVIII ICOMOS · CAHIERS du COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LVIII ICOMOS Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees Herausgegeben vom Nationalkomitee der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Präsident: Prof. -

Media Inquiries

2010 WORLD MONUMENTS FUND/KNOLL MODERNISM PRIZE AWARDED TO BIERMAN HENKET ARCHITECTEN AND WESSEL DE JONGE ARCHITECTEN Award given for restoration of Zonnestraal Sanatorium, in Hilversum, The Netherlands; rescue of iconic building helped launch global efforts to preserve modern architecture at risk. For Immediate Release—New York, NY, October 5, 2010. Bonnie Burnham, president, World Monuments Fund (WMF), announced today that WMF has awarded its 2010 World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize to Bierman Henket architecten and Wessel de Jonge architecten, leading practitioners in the restoration of modern buildings, for their technically and programmatically exemplary restoration of the Zonnestraal Sanatorium (designed 1926–28; completed 1931), in Hilversum, The Netherlands. The sanatorium is a little-known but iconic modernist building designed by Johannes Duiker (1890–1935) and Bernard Bijvoet (1889–1979). The biennial award will Zonnestraal, Main Pavilion, 2004 (post-restoration). Photo courtesy Bierman Henket architecten and Wessel de Jonge architecten. be presented to the Netherlands- based firms at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), on November 18, 2010, by Ms. Burnham; Barry Bergdoll, MoMA’s Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture & Design and chairman of the Prize jury; and Andrew Cogan, CEO, Knoll, Inc. The presentation will be followed by a free public lecture by Messrs. Henket and de Jonge, who will accept the award on behalf of their firms. The World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize is the only prize to acknowledge the specific and growing threats facing significant modern buildings, and to recognize the architects and designers who help ensure their rejuvenation and long-term survival through new design solutions. -

Hannes Meyer's Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at The

Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927-1930) Hideo Tomita The Second Asian Conference of Design History and Theory —Design Education beyond Boundaries— ACDHT 2017 TOKYO 1-2 September 2017 Tsuda University Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927-1930) Hideo Tomita Kyushu Sangyo University [email protected] 29 Abstract Although the Bauhaus’s second director, Hannes Meyer (1889-1954), as well as some of the graduates whom he taught, have been much discussed in previous literature, little is known about the architectural education that Meyer shaped during his tenure. He incorporated key concepts from biology, psychology, and sociology, and invited specialists from a wide variety of fields. The Bauhaus under Meyer was committed to what is considered a “scientific world- view,” and this study focuses on how Meyer incorporated this into his theory of architectural education. This study reveals the following points. First, Meyer and his students used sociology to design analytic architectural diagrams and spatial standardizations. Second, they used psy- chology to design spaces that enabled people to recognize a symbolized community, to grasp a social organization, and to help them relax their mind. Third, Meyer and his students used hu- man biology to decide which direction buildings should face and how large or small that rooms and windows should be. Finally, Meyer’s unified scientific worldview shared a similar theoreti- cal structure to the “unity of science” movement, established by the founding members of the Vienna Circle, at a conceptual level. Keywords: Bauhaus, Architectural Education, Sociology, Psychology, Biology, Unity of Science Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927–1930) 30 The ACDHT Journal, No.2, 2017 Introduction In 1920s Germany, modernist architects began to incorporate biology, sociology, and psychol- ogy into their architectural theory based on the concept of “function” (Gropius, 1929; May, 1929). -

Paimio Sanatorium

MARIANNA HE IKINHEIMO ALVAR AALTO’S PAIMIO SANATORIUM PAIMIO AALTO’S ALVAR ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: : PAIMIO SANATORIUM ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium TIIVISTELMÄ rkkitehti, kuvataiteen maisteri Marianna Heikinheimon arkkitehtuurin histo- rian alaan kuuluva väitöskirja Architecture and Technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio A Sanatorium tarkastelee arkkitehtuurin ja teknologian suhdetta suomalaisen mestariarkkitehdin Alvar Aallon suunnittelemassa Paimion parantolassa (1928–1933). Teosta pidetään Aallon uran käännekohtana ja yhtenä maailmansotien välisen moder- nismin kansainvälisesti keskeisimpänä teoksena. Eurooppalainen arkkitehtuuri koki tuolloin valtavan ideologisen muutoksen pyrkiessään vastaamaan yhä nopeammin teollis- tuvan ja kaupungistuvan yhteiskunnan haasteisiin. Aalto tuli kosketuksiin avantgardisti- arkkitehtien kanssa Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne -järjestön piirissä vuodesta 1929 alkaen. Hän pyrki Paimion parantolassa, siihenastisen uransa haastavim- massa työssä, soveltamaan uutta näkemystään arkkitehtuurista. Työn teoreettisena näkökulmana on ranskalaisen sosiologin Bruno Latourin (1947–) aktiivisesti kehittämä toimijaverkkoteoria, joka korostaa paitsi sosiaalisten, myös materi- aalisten tekijöiden osuutta teknologisten järjestelmien muotoutumisessa. Teorian mukaan sosiaalisten ja materiaalisten toimijoiden välinen suhde ei ole yksisuuntainen, mikä huo- mio avaa kiinnostavia näkökulmia arkkitehtuuritutkimuksen kannalta. Olen ymmärtänyt arkkitehtuurin -

Event Highlights Π100 Years of Bauhaus

Event highlights - 100 years of Bauhaus 2019 all year round Peter Behrens Art and Technology Oberhausen https://veranstaltungen.bauhaus100.de/de/widget/calendar/171 all year round Studio 100 The Ulm School of Design https://www.bauhausstudio100.de/orte/ all year round International touring exhibition on the still unexplored connections to modernism outside of Europe Centre for Art and Media, Karlsruhe all year round Magdeburg pilot rocket Magdeburg https://veranstaltungen.bauhaus100.de/de/widget/calendar/207 all year round International touring exhibition on the still unexplored connections to modernism outside of Europe Centre for Art and Media, Karlsruhe all year round Studio 100 The Ulm School of Design https://www.bauhausstudio100.de/orte/ all year round ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau Bernau http://www.bauhaus-denkmal-bernau.de/ January 23 September 2018 - 20 January 2019 Bauhaus dialogues: chairs from the Löffler collection Steinfurt-Borghorst www.hnbm.de 14 October 2018 - 6 January 2019 Gustav Klimt the magician from Vienna Halle (Saale) https://veranstaltungen.bauhaus100.de/de/widget/calendar/287 9 November 2018 - 10 March 2019 Bauhaus and America Münster https://veranstaltungen.bauhaus100.de/de/widget/calendar/220 10 November 2018 - 10 February 2019 Paul Citroen. People before art Bad Frankenhausen https://veranstaltungen.bauhaus100.de/de/widget/calendar/128 18 November 2018 - 24 February 2019 Wir machen nach Halle (We 'll make it to Halle). Marguerite Friedlaender and Gerhard Marcks Halle (Saale) https://veranstaltungen.bauhaus100.de/de/widget/calendar/265 -

Forms, Ideals, and Methods. Bauhaus Transfers to Mandatory Palestine

Ronny Schüler Forms, Ideals, and Methods. Bauhaus Transfers to Mandatory Palestine Introduction A “Bauhaus style” would be a setback to academic stagnation, into a state of inertia hostile to life, the combatting of which the Bauhaus was once founded. May the Bauhaus be saved from this death. Walter Gropius, 1930 The construction activities of the Jewish community in the British Mandate of Palestine represents a prominent paradigm for the spread of European avant-garde architecture. In the 1930s, there is likely no comparable example for the interaction of a similar variety of influences in such a confined space. The reception of architectural modernism – referred to as “Neues Bauen” in Germany – occurred in the context of a broad cultural transfer process, which had already begun in the wake of the waves of immigration (“Aliyot”) from Eu- rope at the end of the nineteenth century and had a formative effect within the emancipating Jewish community in Palestine (“Yishuv”). Among the growing number of immigrants who turned their backs on Europe with the rise of fas- cism and National Socialism were renowned intellectuals, artists, and archi- tects. They brought the knowledge and experience they had acquired in their 1 On the transfer process of modernity European homelands. In the opposite direction too, young people left to gain using the example of the British Mandate of Palestine, see. Heinze-Greenberg 2011; 1 professional knowledge, which was beneficial in their homeland. Dogramaci 2019; Stabenow/Schüler 2019. Despite the fact that, in the case of Palestine, the broad transfer processes were fueled by a number of sources and therefore represent the plurality of European architectural modernism, the Bauhaus is assigned outstanding 2 importance. -

Redalyc.HANNES MEYER Y LA ESCUELA FEDERAL ADGB: LA

proyecto, progreso, arquitectura ISSN: 2171-6897 [email protected] Universidad de Sevilla España Larripa Artieda, Víctor HANNES MEYER Y LA ESCUELA FEDERAL ADGB: LA SERIE COMO ESTRATEGIA FORMAL proyecto, progreso, arquitectura, núm. 17, julio-diciembre, 2017, pp. 42-55 Universidad de Sevilla Sevilla, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=517655470004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto 17ARQIECRA ESCOLAR EDCACI PROECO PROGRESO ARQIECRA NN HANNES MEYER AND THE ADGB TRADE UNION SCHOOL: SERIES AS A FORMAL STRATEGY or arra rea n enero de 1926 la célebre revista Das Werk pu- dibujar claramente las ideas que Meyer defendía en re- blicó un texto, breve pero intenso, titulado: Die lación a la arquitectura 4. De algún modo, todas las expe- E Neue Welt o El nuevo mundo 1. Su autor, el ar- riencias que el arquitecto había vivido en la década de los quitecto suizo Hannes Meyer, clamaba en este manifiesto años veinte, y que terminaron por configurar su ideario, un cambio inminente en el modo de concebir el arte y la se encuentran latentes en tales textos: su participación arquitectura, a la luz de todas las transformaciones que en el movimiento cooperativista suizo, su alineación con implicaba la cultura moderna. “ Cada época demanda el ideario radical de izquierda, su producción artística N annes eer ue uno e los arueos ás oroeos on las eas el ala raal el raonalso ue l su nueva forma –escribe Meyer– Es tarea nuestra dar al agrupada bajo el nombre Co–op , su participación en so oros ranes arueos oo ar a ans er arel ee u lberseer o rns a esarrollaron nuevo mundo una nueva configuración con los medios la asociación de arquitectos ABC, su fascinación por el urane la aa e los aos ene u oluna e esnular la arueura el –ar burus e oo sbolso roo del presente ”2. -

Opens in a Cascade of Trapezoidal Shapes, Like Shards of Glass

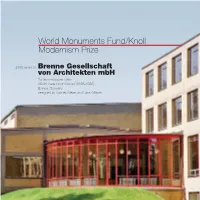

World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize 2008 award to Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH For the restoration of the ADGB Trade Union School (1928–1930) Bernau, Germany designed by Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer 1 2 This restoration highlights and emphasizes a particular approach to historic preservation that is perhaps the most sensible and intellectually satisfying today. Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten is probably Germany’s most engaged and thoughtful restorer of classic Modern architecture. —Dietrich NeumaNN, JUROR Pre-restoration During the period in which the ADGB building was under East German control, it was impossible to find appropriate glass for repairs, so the light-filled glass corridor was obscured by a wooden parapet. Brenne Gesellschaft von Architekten restored the original materials and reintroduced the original bright red color of the steel framing. 3 Many of the building’s steel casement windows are highly articulated. The glass in the external staircase opens in a cascade of trapezoidal shapes, like shards of glass. 4 Despite Modernism’s influential place in our architectural heritage, many significant Modern buildings are endangered because of neglect, perceived obsolescence, inappropriate renovation, or even the imminent danger of demolition. In response to these threats, in 2006, the World Monuments Fund launched its Modernism at Risk Initiative with generous support from founding sponsor Knoll, Inc. The World Monuments Fund/Knoll Modernism Prize was established as part of this initiative to demonstrate that Modern buildings can remain sustainable structures with vital futures. The Prize, which will be awarded biennially, recognizes innovative architectural and design solutions that preserve or enhance Modern landmarks and advances recognition of the special challenges of conserving Modern architecture. -

Nominations to the World Heritage List

World Heritage 41 COM WHC/17/41.COM/8B Paris, 19 May 2017 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Forty-first session Krakow, Poland 2-12 July 2017 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8B. Nominations to the World Heritage List SUMMARY This document presents the nominations to be examined by the Committee at its 41st session (Krakow, 2017). It is divided into two sections: Part I Examination of nominations of natural, mixed and cultural sites to the World Heritage List Part II Record of the physical attributes of each site being discussed at the 41st session The document presents for each nomination the proposed Draft Decision based on the recommendations of the appropriate Advisory Body(ies) as included in WHC/17/41.COM/INF.8B1 and WHC/17/41.COM/INF.8B2, and it provides a record of the physical attributes of each site being discussed at the 41st session. The information is presented in two parts: • a table of the total surface area of each site and any buffer zone proposed, together with the geographic coordinates of each site's approximate centre point; and • a set of separate tables presenting the component parts of each of the 15 proposed serial sites. Decisions required: The Committee is requested to examine the recommendations and Draft Decisions presented in this Document, and, in accordance with paragraph 153 of the Operational Guidelines, take its Decisions concerning inscription on the World Heritage List in the following four categories: (a) properties which it inscribes on the World Heritage List; (b) properties which it decides not to inscribe on the World Heritage List; (c) properties whose consideration is referred; (d) properties whose consideration is deferred. -

100 Years of Bauhaus

Excursions to the Visit the Sites of the Bauhaus Sites of and the Bauhaus Modernism A travel planner and Modernism! ↘ bauhaus100.de/en # bauhaus100 The UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the Sites of Bauhaus Modernism Hamburg P. 31 Celle Bernau P. 17 P. 29 Potsdam Berlin P. 13 Caputh P. 17 P. 17 Alfeld Luckenwalde Goslar Wittenberg P. 29 P. 17 Dessau P. 29 P. 10 Quedlinburg P. 10 Essen P. 10 P. 27 Krefeld Leipzig P. 27 P. 19 Düsseldorf Löbau Zwenkau Weimar P. 19 P. 27 Dornburg Dresden P. 19 Gera P. 19 P. 7 P. 7 P. 7 Künzell P. 23 Frankfurt P. 23 Kindenheim P. 25 Ludwigshafen P. 25 Völklingen P. 25 Karlsruhe Stuttgart P. 21 P. 21 Ulm P. 21 Bauhaus institutions that maintain collections Modernist UNESCO World Heritage Sites Additional modernist sites 3 100 years of bauhaus The Bauhaus: an idea that has really caught on. Not just in Germany, but also worldwide. Functional design and modern construction have shaped an era. The dream of a Gesamtkunst- werk—a total work of art that synthesises fine and applied art, architecture and design, dance and theatre—continues to this day to provide impulses for our cultural creation and our living environments. The year 2019 marks the 100 th anniversary of the celebration, but the allure of an idea that transcends founding of the Bauhaus. Established in Weimar both time and borders. The centenary year is being in 1919, relocated to Dessau in 1925 and closed in marked by an extensive programme with a multitude Berlin under pressure from the National Socialists in of exhibitions and events about architecture 1933, the Bauhaus existed for only 14 years. -

The Rise and Fall of the Tuberculosis Sanitarium in Response to the White Plague a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE TUBERCULOSIS SANITARIUM IN RESPONSE TO THE WHITE PLAGUE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE HISTORIC PRESERVATION BY ANYA GRAHN (EDWARD WOLNER) BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of my thesis committee. I must first thank Architecture Professor Edward Wolner for his patience with me, his guidance, and for sharing his wealth of knowledge about modernist architecture and architects, Johannes Duiker and Alvar Aalto, in particular. Secondly, I am incredibly grateful to History Professor Nina Mjagkij, a former consumptive, for directing my research and organization of this thesis. Finally, I am appreciative of Architecture instructor Cynthia Brubaker’s support of my initial research, eagerness to learn more about tuberculosis sanitariums, and willingness to serve on this committee. I am also thankful to my MSHP colleagues Emily Husted, Kelli Kellerhals, and Chris Allen. The four of us formed a student thesis committee, meeting weekly to set goals for our research and writing, discussing our topics, and keeping one another on task. It is very possible that this thesis would not have been completed without them. I would also like to acknowledge the help provided to me in researching Kneipp Springs Sanitarium. Bridgett Cox at the Hope Springs Library was very helpful, responding to my email requests and introducing me to the Scrapbooks of M.F. Owen: Rome City Area History that played such a pivotal role in my research of this institution. -

Jury Selects Germany-Wide Grand Tour of Modernism Sites

1 of 4 Press Release: 8th March 2018 Andrea Brandis Communication 100 jahre bauhaus T +49 (0)3643 545-485 Kathrin Luz Press Office 100 jahre bauhaus Communication T +49 (0)171- 3102472 Press @ bauhaus100.de www bauhaus100.de 100 jahre bauhaus Jury Selects Germany-wide Geschäftsstelle Grand Tour of Modernism Sites. Bauhaus Verbund 2019 Steubenstraße 15 99423 Weimar Weimar/Berlin, 8th March 2018 Today, the jury’s choices for the Grand Tour of Modernism will be presented today at ITB Berlin. Reviewing over 460 proposals, jury members have selected the sites that will complement the centenary programme as the Route of Modernism. What does Alfeld have in common with Berlin, Darmstadt, Dresden, Stuttgart and Bernau? The Grand Tour of Modernism. It will guide visitors along a specially conceived route, which can be explored by rail, car or bicycle, through the history of modernism from 1900 to 2000. The Grand Tour articulates an integrative approach to architecture – addressing facets that range from cultural history references and the use of new materials to the broader socio-political context. Through this approach, the Grand Tour of Modernism links travel with the joy of discovery and insights into the past and present. It spans individual buildings and housing estates: icons and controversial projects, key works of architecture and new discoveries. This Germany-wide project is also emblematic of close cooperation with organisations on the spot, as well as local tourism associations and the federal states’ marketing organisations; it has been made possible thanks to support from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media (BKM).