Forms, Ideals, and Methods. Bauhaus Transfers to Mandatory Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2010-2011

???Editorial Dear Readers, We thought long and hard about us! Founder of WIZO and first president Rebecca Sieff looks what to put into this special 90th back over the first 40 years (page 32) – and WIZO Review anniversary edition of WIZO Assistant Editor Tricia Schwitzer writes an imaginary letter Review. At 90 years young, we to Rebecca – and asks ‘How have we done?’ (page 33). want to look forward, but at the same time, remember the past. The article on pages 34-35 features a new project about And we decided to do both – to start in WIZO’s schools: teaching the students about but in an unusual way. In this WIZO. Based on a worldwide popular game, this was the issue, WIZO chaverot speak – brainchild of World WIZO’s Education Division Chairperson, both historically and currently. Ruth Rubinstein. Amongst some old issues of WIZO Review, there are some WIZO.uk chairman Loraine Warren is the subject of our first-hand accounts of the very first days of WIZO. And it was Interview (pages 36-37) for this issue. Loraine tells us how quite amazing how some of those articles blended in with proud she is to be part of the WIZO family and how fulfilling what we were planning. The magazine from 1960, marking a career it can be. WIZO’s 40th anniversary, is a wealth of original experiences – with articles written by the very women who were there We all are so proud of our WIZO husbands – how they support at the beginning. us! Read (on page 38) what an anonymous Canadian WIZO husband says in WIZO Review December 1946 – he belongs Everyone in Israel and our friends around the world will to the Loyal Order of WIZO Husbands. -

Israel Monopoly Ohne Grenzen

Viktoria Waltz ISRAEL Politische Raumplanung Ethnozentrismus Rassismus MONOPOLY OHNE GRENZEN Kurzfassung Israel ist das Produkt eines Raumplanungsprozesses, der einem riskanten Monopoly gleicht: höchste Einsätze um Boden, Besiedlung und Bevölkerung. Raumplanung entpuppt sich dabei als ein umfassendes Herrschaftsinstrument zur Sicherung des Monopols über Palästina. Israel ist das Ergebnis eines zionistischen Großraumprojekts, dessen Ergebnis heute eine rassistische Gesellschaft ist, die sich jüdisch national definiert und einen ethnisch reinen, jüdischen Staat anstrebt. Um den bestehenden jüdischen Staat ‚reinen Blutes‘ zu halten, hetzen fundamentalistische Rabbiner ihre jüdischen Landsleute auf, keine Heirat mit Nicht-Juden einzugehen, keine Häuser und Wohnungen an Araber zu vermieten, usw. 1 Die Regierung, besonders das zionistische Regime in seiner jüngsten Ausprägung, setzt sämtliche ihr zur Verfügung stehenden Mittel ein, um die in Israel lebenden Palästinenser kaltzustellen und die in den besetzten Gebieten lebenden Palästinenser zu drangsalieren, um schließlich möglichst alle zu vertreiben. Das zionistische Regime – voran die zentralen Institutionen World Zionist Organization (WZO), Jewish Agency (JA) und Jewish National Fund (JNF), im Einklang mit fanatischen Siedlern, die eine ‚End-Erlösung‘ im jüdischen Sinne aktiv betreiben wollen - ist dabei, die zionistisch- jüdische Herrschaft auf das gesamte Gebiet Palästinas auszudehnen, wie es zu Mandatszeiten versprochen wurde und die Palästinenser so weit zu demütigen, dass sie entweder -

(Government of Upalestine

OF THE (Government of UPalestine. PUBLISHED FORTNIGHTLY BY AUTHORITY. No. 260 JERUSALEM 1st Jane, 1930. CONTENTS Page 5. GOVERNMENT NOTICES. (a) Confirmation of Ordinances Nos. 7 and 8 of 1930 ... 412 (b) Appointments, etc. 413 (c) Appointment of Coroner ... 413 (d) Appointment of Consul 413 regarding ,1926׳ ,e) Certificate under the Expropriation of Land Ordinance) 1he construction of Government Offices at Nablus ... 414 (f) Certificate under the Expropriation of Land Ordinance, 1926, regarding the opening of a quarry at Beit Sahur. village ... ... ... 414 (g) Order under the Police Ordinance, 1926, appointing a Superior Police Officer ... 414 (h) Order under the Determination of Areas of Municipalities Ordinance, 1925, determining the Municipal Area of Tulkarem ... ... ... 415 (i) Order under the Regulation of Trades and Industries Ordinance, 1927, regarding addition to Schedule ... ... ... ... ... ... 416 (j) Order under the Width and Alignment of Roads Ordinances, 1926-1927, regarding certain roads ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 416-417 (k) Orders under the Urban Property Tax Ordinances, 1928-1929, appointing Revision Appeal Commissions in J alia, Gaza, llamleh and Lydda ... 417-419 (7) Order under the the Land Settlement Ordinance, 1928, regarding settlement in the Gaza Sub-District ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 419 {m) Rule under the Trade Marks Ordinance, 1921, regarding addition to Schedule ... 419-420 (n) Rule under the Patents and Designs Ordinance, 1924, regarding addition 420 ־ " ..." :.. "... to Schedule (0) Rule under the Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1926, regarding movement of cattle ... ... ... ... ... 420 (p) Notices under the Diseases of Animals Ordinance, 1926, declaring certain villages to be infected areas ... .,. ... ... ... ... 421 (q) Notice under the Bills of Exchange Ordinance, 1929, regarding legal holidays ... 422 (r) Notice under the Customs Ordinance, 1929, regarding shipment of local produce 422-423 (s) Notice regarding immigration to the Union of South Africa .. -

Greening the White City

GREENING THE WHITE CITY International Conference 1-3 May 2013 “Habima”- National Theater, Tel Aviv The City of Tel Aviv In cooperation with the Heinrich Boell Foundation and the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation No other city in the world can boast as large a portfolio of so-called International Style architecture as Tel Aviv. This heritage only recaptured public awareness in the mid-1980s as a result of an exhibition, with UNESCO ultimately naming Tel Aviv a world heritage site in 2003. Since then, Israel’s latest metropolitan city has enjoyed a unique reputation across the globe as the “White City”. This particular architectural style, which harks back to the traditions of Bauhaus style architecture, and especially the International Style of modern architecture, is attributed to the influx of Jewish refugees from Europe. Today, this style is giving Israel’s “secret capital of culture” new self-assurance. In the 21st century, the cultural heritage left by Bauhaus style architecture is presenting the city with new challenges: exploding real estate prices, huge increases in rent, and a loss of social living space. As Israel’s modern centre, Tel Aviv is also looking to lead the way in terms of green redevelopment and the energy-efficiency refurbishment of buildings, because the pressure to achieve greater energy efficiency and build ecologically is mounting. Through the “Greening the White City” conference, we provide a platform for reflecting on the eco-friendly and culture-sensitive issues of the Bauhaus heritage. During the symposium and workshops, experts and activists from Germany and Israel will share practical energy-efficiency refurbishment solutions that take the cultural heritage of the buildings in the White City into account. -

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism IC I ICOMOS COMOS O M OS

Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne Welterbevorschläge aus Mittel- und Osteuropa Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism World Heritage Proposals from Central and Eastern Europe Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne SocialistSocialist Modernism Realism and III V L S EE T MI O ALK N O I T A N N E CH S UT E D S ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES LVIII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LVIII ICOMOS · HEFTE DE ICOMOS ICOMOS · CAHIERS DU COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LVIII Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism I NTERNATIONAL COUNCIL on MONUMENTS and SITES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SITES CONSEJO INTERNACIONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SITIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne. Welterbevorschläge aus Mittel- und Osteuropa Dokumentation des europäischen Expertentreffens von ICOMOS über Möglichkeiten einer internationalen seriellen Nominierung von Denkmalen und Stätten des 20. Jahrhunderts in postsozialistischen Ländern für die Welterbeliste der UNESCO – Warschau, 14.–15. April 2013 – Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism. World Heritage Proposals from Central and Eastern Europe Documentation of the European expert meeting of ICOMOS on the feasibility of an international serial nomination of 20th century monuments and sites in post-socialist countries for the UNESCO World Heritage List – Warsaw, 14th–15th of April 2013 – ICOMOS · H E F T E des D E U T S CHEN N AT I ONAL KO MI T E E S LVIII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LVIII ICOMOS · CAHIERS du COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LVIII ICOMOS Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees Herausgegeben vom Nationalkomitee der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Präsident: Prof. -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

Hannes Meyer's Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at The

Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927-1930) Hideo Tomita The Second Asian Conference of Design History and Theory —Design Education beyond Boundaries— ACDHT 2017 TOKYO 1-2 September 2017 Tsuda University Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927-1930) Hideo Tomita Kyushu Sangyo University [email protected] 29 Abstract Although the Bauhaus’s second director, Hannes Meyer (1889-1954), as well as some of the graduates whom he taught, have been much discussed in previous literature, little is known about the architectural education that Meyer shaped during his tenure. He incorporated key concepts from biology, psychology, and sociology, and invited specialists from a wide variety of fields. The Bauhaus under Meyer was committed to what is considered a “scientific world- view,” and this study focuses on how Meyer incorporated this into his theory of architectural education. This study reveals the following points. First, Meyer and his students used sociology to design analytic architectural diagrams and spatial standardizations. Second, they used psy- chology to design spaces that enabled people to recognize a symbolized community, to grasp a social organization, and to help them relax their mind. Third, Meyer and his students used hu- man biology to decide which direction buildings should face and how large or small that rooms and windows should be. Finally, Meyer’s unified scientific worldview shared a similar theoreti- cal structure to the “unity of science” movement, established by the founding members of the Vienna Circle, at a conceptual level. Keywords: Bauhaus, Architectural Education, Sociology, Psychology, Biology, Unity of Science Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927–1930) 30 The ACDHT Journal, No.2, 2017 Introduction In 1920s Germany, modernist architects began to incorporate biology, sociology, and psychol- ogy into their architectural theory based on the concept of “function” (Gropius, 1929; May, 1929). -

Sociographie De La Doxa Coloniale Israélienne

Université de Montréal Se représenter dominant et victime : sociographie de la doxa coloniale israélienne par Michaël Séguin Département de sociologie Faculté des arts et sciences Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.) en sociologie Août 2018 © Michaël Séguin, 2018 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales Cette thèse intitulée : Se représenter dominant et victime : sociographie de la doxa coloniale israélienne Présentée par : Michaël Séguin a été évaluée par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Deena White, présidente-rapporteuse et représentante du doyen Paul Sabourin, directeur de recherche Yakov Rabkin, codirecteur de recherche Barbara Thériault, membre du jury Rachad Antonius, examinateur externe Résumé Dans un monde majoritairement postcolonial, Israël fait figure d’exception alors même que se perpétue sa domination d’un autre peuple, les Arabes palestiniens. Tandis qu’un nombre grandissant d’auteurs, y compris juifs, traitent de la question israélo-palestinienne comme d’un colonialisme de peuplement, et non plus comme d’un conflit ethnique entre groupes nationaux, se pose la question : comment une telle domination est-elle possible à l’ère des médias de masse ? Plus précisément, pourquoi cette domination est-elle si peu contestée de l’intérieur de la société israélienne alors même qu’elle contredit le discours public de l’État qui tente, par tous les moyens, de se faire accepter comme étant démocratique et éclairé ? Pour y répondre, cette thèse procède à une analyse de la connaissance de sens commun israélienne afin de détecter à la fois le mode de connaissance, issu des relations sociales, privilégié pour faire sens des rapports ethnonationaux, mais aussi la manière dont cette doxa vient légitimer la domination des Palestiniens. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

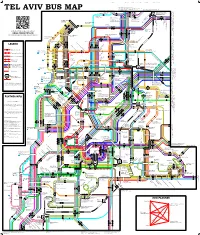

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Shifts in Modernist Architects' Design Thinking

arts Article Function and Form: Shifts in Modernist Architects’ Design Thinking Atli Magnus Seelow Department of Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology, Sven Hultins Gata 6, 41296 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-72-968-88-85 Academic Editor: Marco Sosa Received: 22 August 2016; Accepted: 3 November 2016; Published: 9 January 2017 Abstract: Since the so-called “type-debate” at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne—on individual versus standardized types—the discussion about turning Function into Form has been an important topic in Architectural Theory. The aim of this article is to trace the historic shifts in the relationship between Function and Form: First, how Functional Thinking was turned into an Art Form; this orginates in the Werkbund concept of artistic refinement of industrial production. Second, how Functional Analysis was applied to design and production processes, focused on certain aspects, such as economic management or floor plan design. Third, how Architectural Function was used as a social or political argument; this is of particular interest during the interwar years. A comparison of theses different aspects of the relationship between Function and Form reveals that it has undergone fundamental shifts—from Art to Science and Politics—that are tied to historic developments. It is interesting to note that this happens in a short period of time in the first half of the 20th Century. Looking at these historic shifts not only sheds new light on the creative process in Modern Architecture, this may also serve as a stepstone towards a new rethinking of Function and Form. Keywords: Modern Architecture; functionalism; form; art; science; politics 1.