Rescue by Jews During the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Origin Story

L’CHAYIM www.JewishFederationLCC.org Vol. 41, No. 11 n July 2019 / 5779 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Our origin story 6 Our Community By Brian Simon, Federation President 7 Jewish Interest very superhero has an origin to start a High School in Israel pro- people 25 years old or younger to trav- story. Spiderman got bit by a gram, and they felt they needed a local el to Israel to participate in volunteer 8 Marketplace Eradioactive spider. Superman’s Federation to do that. So they started or educational programs. The Federa- father sent him to Earth from the planet one. The program sent both Jews and tion allocates 20% of its annual budget 11 Israel & the Jewish World Krypton. Barbra non-Jews to study in Israel. through the Jewish Agency for Israel 14 Commentary Streisand won a Once the Federation began, it (JAFI), the Joint Distribution Commit- 16 From the Bimah talent contest at a quickly grew and took on new dimen- tee (JDC) and the Ethiopian National gay nightclub in sions – dinner programs, a day camp, Project (ENP) to social service needs 18 Community Directory Greenwich Vil- a film festival and Jewish Family Ser- in Israel, as well as to support Part- 19 Focus on Youth lage. vices. We have sponsored scholarships nership Together (P2G) – our “living Our Jewish and SAT prep classes for high school bridge” relationship with the Hadera- 20 Organizations Federation has its students (both Jews and non-Jews). We Eiron Region in Israel. 22 Temple News own origin story. stopped short of building a traditional In the comics, origin stories help n Brian There had already Jewish Community Center. -

A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music & Videos by Holocaust

Bearing Witness BEARING WITNESS A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music, and Videos by Holocaust Victims and Survivors PHILIP ROSEN and NINA APFELBAUM Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut ● London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Philip. Bearing witness : a resource guide to literature, poetry, art, music, and videos by Holocaust victims and survivors / Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0–313–31076–9 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Bio-bibliography. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Bio-bibliography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in art—Catalogs. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Songs and music—Bibliography—Catalogs. 5. Holocaust,Jewish (1939–1945)—Video catalogs. I. Apfelbaum, Nina. II. Title. Z6374.H6 R67 2002 [D804.3] 016.94053’18—dc21 00–069153 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00–069153 ISBN: 0–313–31076–9 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii Historical Background of the Holocaust xi 1 Memoirs, Diaries, and Fiction of the Holocaust 1 2 Poetry of the Holocaust 105 3 Art of the Holocaust 121 4 Music of the Holocaust 165 5 Videos of the Holocaust Experience 183 Index 197 Preface The writers, artists, and musicians whose works are profiled in this re- source guide were selected on the basis of a number of criteria. -

Joan Campion. in the Lion's Mouth: Gisi Fleischmann and the Jewish Fight for Survival

Gorbachev period) that, "As a liberal progressive reformer, and friend of the West, Gorbachev is ... a figment of Western imagination." One need not see Gorbachev as a friend or a liberal, of course, to understand that he in- tended from the outset to change the USSR in fundamental ways. To be sure, there are some highlights to this book. Chapter 4 by Gerhard Wettig (of the Bundesinstitut fiir Ostwissenschaftliche und Internationale Studien) discusses important conceptual distinctions made by the Soviets in their view of East-West relations. Finn Sollie, of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Norway, provides a balanced and insightful consideration of Northern Flank security issues. This is not the book it could have been given the talented people involved in the conferences that led to such a volume. Given the timing of its produc- tion (during the first two years of Gorbachev's rule), the editors should have done much more to seek up-dated and more in-depth analyses from the contributors. As it stands, Cline, Miller and Kanet have given us a foot- note in the record of a waning Cold War. Daniel N. Nelson University of Kentucky Joan Campion. In the Lion's Mouth: Gisi Fleischmann and the Jewish Fight for Survival. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987. xii, 152 pp. $24.50 (cloth), $12.75 (paper). The immense accumulation of scholarship on the Holocaust and World War II made possible the emergence of a new genre of literature portraying heroic figures engaged in rescue work in terror-ridden Nazi Europe. The last decade has seen the publication of a spate of books including the sagas of Raoul Wallenberg, Hanna Senesh and Janusz Korczak, drawing on extensive source material as well as previous literature. -

Gadol Beyisrael Hagaon Hakadosh Harav Chaim Michoel Dov

Eved Hashem – Gadol BeYisrael HaGaon HaKadosh HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L (4. Cheshvan 5664/ 25. Oktober 1903, Debrecen, Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia – 6 Kislev 5718/ 29. November 1957, Mount Kisco, New York) Евед ХаШем – Гадоль БеИсраэль ХаГаон ХаКадош ХаРав Хаим-Михаэль-Дов Вайсмандель; Klenot medzi Klal Yisroel, Veľký Muž, Bojovník, Veľký Tzaddik, vynikajúci Talmid Chacham. Takýto človek príde na svet iba raz za pár storočí. „Je to Hrdina všetkých Židovských generácií – ale aj pre každého, kto potrebuje príklad odvážneho človeka, aby sa pozrel, kedy je potrebná pomoc pre tých, ktorí sú prenasledovaní a ohrození zničením v dnešnom svete.“ HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L, je najväčší Hrdina obdobia Holokaustu. Jeho nadľudské úsilie o záchranu tisícov ľudí od smrti, ale tiež pokúsiť sa zastaviť Holokaust v priebehu vojny predstavuje jeden z najpozoruhodnejších príkladov Židovskej histórie úplného odhodlania a obete za účelom záchrany Židov. Nesnažil sa zachrániť iba niektorých Židov, ale všetkých. Ctil a bojoval za každý Židovský život a smútil za každou dušou, ktorú nemohol zachrániť. Nadľudské úsilie Rebeho Michoela Ber Weissmandla oddialilo deportácie viac ako 30 000 Židov na Slovensku o dva roky. Zohral vedúcu úlohu pri záchrane tisícov životov v Maďarsku, keď neúnavne pracoval na zverejňovaní „Osvienčimských protokolov“ o nacistických krutostiach a genocíde, aby „prebudil“ medzinárodné spoločenstvo. V konečnom dôsledku to ukončilo deportácie v Maďarsku a ušetrilo desiatky tisíc životov maďarských Židov. Reb Michoel Ber Weissmandel bol absolútne nebojácny. Avšak, jeho nebojácnosť sa nenarodila z odvahy, ale zo strachu ... neba. Každý deň, až do svojej smrti ho ťažil smútok pre milióny, ktorí nemohli byť spasení. 1 „Prosím, seriózne študujte Tóru,“ povedal HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L svojim študentom, "spomína Rav Spitzer. -

Thesis Front Matter

Memories of Youth: Slovak Jewish Holocaust Survivors and the Nováky Labor Camp Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Antony Polonsky & Joanna B. Michlic, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Karen Spira May 2011 Copyright by Karen Spira ! 2011 ABSTRACT Memories of Youth: Slovak Jewish Holocaust Survivors and the Nováky Labor Camp A thesis presented to the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Karen Spira The fate of Jewish children and families is one of the understudied social aspects of the Holocaust. This thesis aims to fill in the lacuna by examining the intersection of Jewish youth and families, labor camps, and the Holocaust in Slovakia primarily using oral testimonies. Slovak Jewish youth survivors gave the testimonies to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, Israel. Utilizing methodology for examining children during the Holocaust and the use of testimonies in historical writing, this thesis reveals the reaction of Slovak Jewish youth to anti-Jewish legislation and the Holocaust. This project contributes primary source based research to the historical record on the Holocaust in Slovakia, the Nováky labor camp, and the fate of Jewish youth. The testimonies reveal Jewish daily life in pre-war Czechoslovakia, how the youth understood the rise in antisemitism, and how their families ultimately survived the Holocaust. Through an examination of the Nováky labor camp, we learn how Jewish families and communities were able to remain together throughout the war, maintain Jewish life, and how they understood the policies and actions enacted upon them. -

Marianne Cohn Et Son Action De Résistance

Ruth Fivaz-Silbermann Historienne, Genève Marianne Cohn et son action résistante L'action L'action de Marianne Cohn à la frontière franco-suisse s'inscrit dans le travail de la Résistance juive au plan d'extermination des nazis. Marianne fait partie d'un réseau créé au printemps 1942, appelé «Mouvement de la Jeunesse sioniste». Ce réseau procure des caches et des faux papiers aux juifs étrangers ou français, menacés sur tout le territoire d'arrestation et de déportation, parce qu'ils sont juifs. Il travaille en étroite collaboration avec le réseau des Eclaireurs israélites de France. Leur objectif principal est de sauver des enfants et des adolescents juifs, notamment en les faisant passer en Suisse. La Suisse a autorisé, fin 1943, l'arrivée de 1'500 enfants juifs de France. Après avoir travaillé à Moissac, à Nice et à Grenoble, Marianne, qui a 21 ans, est chargée début 1944 par son réseau de convoyer des groupes d'enfants et de jeunes vers la Suisse, à la frontière genevoise. Elle travaille sous les ordres de Simon Lévitte, chef du mouvement, et d'Emmanuel «Mola» Racine, chef du service de passage en Suisse et frère de Mila Racine, qui a été arrêtée sur cette même frontière le 21 octobre précédent. L’équipe compte cinq ou six résistants, dont Hélène Bloch, Rolande Birgy et Colette Dufournet. Mais Marianne sera la plus active: elle convoie neuf groupes d'enfants en avril et mai 1944, soit 207 enfants au total. Hélas, elle est arrêtée le 31 mai 1944, avec les 32 enfants de son dernier convoi. -

Y University Library

Y university library Fortuno≠ Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies professor timothy snyder Advisor PO Box 208240 New Haven CT 06520-8240 t 203 432-1879 web.library.yale.edu/testimonies Episode 6 — Renee Hartman Episode Notes by Dr. Samuel Kassow Renee Glassner Hartman was born in 1933 in Bratislava (Pressburg in German, Poszonyi in Hungarian). She had a younger sister, Herta, born in 1935. Their parents, like Herta, were deaF. Their father was a jeweler. This is the story oF two young children who were raised in a loving, religiously observant home and who experienced the traumatic and sudden destruction oF their childhood, the loss oF their parents, and their own deportation to the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, from which they were liberated by the British in 1945. As they struggled to stay alive, Renee and Herta were inseparable. No matter how depressed and distraught she became, Renee never forgot that her younger sister, unable to hear, totally depended on her. Together they survived a long nightmare that included betrayal, physical violence, liFe-threatening disease, and hunger. During the time when Renee and Herta were born, the Jews oF Bratislava lived in relative peace and security. BeFore World War I, most Jews in Bratislava had spoken Magyar or German (German was the language in Renee’s home). Between the wars they also had to learn Slovak as Bratislava, formerly under Hungarian administration, became part oF the new Czechoslovak state, which was founded in 1918. Under the leadership oF President Thomas Masaryk, Czechoslovakia was a democracy, and somewhat more prosperous than countries like Poland and Hungary. -

Xxi 85 2014 ANO XXI - Setembro 2014 - Nº 85

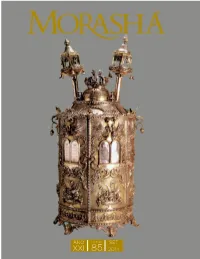

set 2014 edição 85 ANO xXI ANO XXI - edição 85 setembro 2014 ANO XXI - Setembro 2014 - nº 85 CAPA TIK (estojo para guardar a Torá) em madeira revestida de prata, com RIMONIM (enfeites no feitio de romãs) Paris, circa 1860 Carta ao leitor O Povo Judeu sempre se une diante de grandes desafios. As cartas de leitores enviadas aos principais jornais do Os últimos meses foram tempos difíceis, tanto para os país revelam que o povo brasileiro também compreende a judeus que vivem em Israel como para os da Diáspora. Em situação de Israel. Somos muitos gratos a todos aqueles que Israel, nosso povo luta contra grupos fundamentalistas que estão ao nosso lado durante esta época difícil. declaram publicamente que visam a aniquilar o Estado É importante ressaltar que, durante o conflito em Gaza, de Israel e exterminar todo o Povo Judeu. Fora de Israel, muitos países árabes, que costumam condenar Israel de os judeus enfrentam o ressurgimento do antissemitismo antemão, mantiveram-se em silêncio. Vários deles, que ostensivo e violento. Não há mais como negar que nem sequer reconhecem a existência do Estado de Israel, antissionismo é uma forma disfarçada de antissemitismo. culparam os grupos que controlam Gaza pelo conflito. Essa O atual conflito entre Israel e as organizações terroristas que mudança de postura política é resultado das atrocidades controlam Gaza se iniciou com o sequestro e assassinato de que ocorrem, atualmente, no Oriente Médio. Os líderes três jovens judeus, seguido pelo lançamento de milhares de árabes moderados finalmente se conscientizaram de que o mísseis contra as principais cidades israelenses. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE TEACHER’S GUIDE Daring to Resist: Jewish Defiance in the Holocaust TABLE OF CONTENTS Curator’s Introduction, by Yitzchak Mais Teaching a New Approach to the Holocaust: The Jewish Narrative 2 How to Use this Guide 4 Classroom Lesson Plan for Pre-Visit Activities (for all schools) 5 Responding to the Nazi Rise to Power 8 On Behalf of the Community 10 Documenting the Unimaginable 12 Physical and Spiritual Resistance 14 Pre- or Post-Visit Lesson Plans (for Jewish schools) 16 Maintaining Jewish Life: The Resistance of Rabbi Ephraim Oshry 17 Resistance of the Working Group: Rabbi Michael Dov Ber Weissmandel and Gisi Fleischmann 25 Ethical Wills from the Holocaust: A Final Act of Defiance 36 Additional Resources 48 Photo Credits 52 This Teacher’s Guide is made possible through the generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany: The Rabbi Israel Miller Fund for Shoah Research, Documentation and Education. TEACHER’S GUIDE / DARING TO RESIST: Jewish Defiance in the Holocaust 1 Curator’s Introduction — by Yitzchak Mais TEACHING A NEW APPROACH TO THE HOLOCAUST: THE JEWISH NARRATIVE ix decades after the liberation of Auschwitz, the Holocaust is indisputably recognized as a watershed event whose ramifications have critical significance for Jews and non-Jews alike. As educators we are deeply concerned with how the Holocaust has been absorbed into the historical consciousness of Ssociety at large, and among Jews in particular. Awareness of the events of the Holocaust has dramatically increased since the 1980s, with a surge of books, movies, and educational curricula, as well as the creation of Holocaust memorials, museums, and exhibitions worldwide. -

Lettre R”Sistance N¡38

LA LETTRE de la Fondation de la Résistance Reconnue d’utilité publique par décret du 5 mars 1993. Sous le Haut Patronage du Président de la République N° 38 - septembre 2004 - 4,50 € Le débarquement de Provence et la Résistance Commission archives SAUVEGARDER LES ARCHIVES PRIVÉES DE LA RÉSISTANCE ET DE LA DÉPORTATION : UNE EXPOSITION VOUS Y AIDE. Sauvegarder les archives de la Résistance et de la Déportation est l'une des conditions pour permettre d’écrire l’histoire de cette période et pour préserver la mémoire. À cet effet, en partenariat avec le Crédit municipal de Paris, les Fondations de la Résistance et pour la Mémoire de la Déportation, associées aux ministères de la Défense et de la Culture, viennent de réaliser une exposition qui aidera tous les détenteurs d’archives, à les préserver et à les transmettre. L’objectif de l’exposition « Ensemble, sauvegardons et les archives des associations, en insistant sur le fait les archives privées de la Résistance et de la Dépor- que tous ces documents sont intéressants pour les his- tation » est de sensibiliser tous les particuliers possé- toriens futurs ; dant des documents relatifs à l'histoire de la Résistance - « La sauvegarde des archives est un devoir » insiste et de la Déportation, quelle que soit leur origine et sur les avantages qu’il y a pour un particulier à céder leur forme - écrits personnels, archives des organisa- ses papiers à un centre public d’archives qui seul offre tions de Résistance et des associations dédiées à la le maximum de garanties tant du point de vue de la mémoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, des- conservation des documents que de leur communi- sins, textes, tracts, faux papiers.. -

The Holocaust As Public History

The University of California at San Diego HIEU 145 Course Number 646637 The Holocaust as Public History Winter, 2009 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Class meets 12---12:50 in Center 113 Please do not send me email messages. Best time to talk is right after class. It is fine to call my office during office hours. You may send a message to me on the Mail section of our WebCT. You may also get messages to me via Ms Dorothy Wagoner, Judaic Studies Program, 858 534 4551; [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 2-3 and Mondays 11-12 Holocaust Living History Workshop Project Manager: Ms Theresa Kuruc, Office in the Library: Library Resources Office, last cubicle on the right [turn right when you enter the Library] Phone: 534 7661 Email: [email protected] Office hours in her Library office: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 and by appointment Ms Kuruc will hold a weekly two hour open house in the Library Electronic Classroom, just inside the entrance to the library to the left, on Wednesday evenings from 5-7. Students who plan to use the Visual History Archive for their projects should plan to work with her there if possible. If you are working with survivors or high school students, that is the time and place to work with them. Reader: Mr Matthew Valji, [email protected] WebCT The address on the web is: http://webct.ucsd.edu. Your UCSD e-mail address and password will help you gain entry. Call the Academic Computing Office at 4-4061 or 4-2113 if you experience problems. -

Swedish Interventions in the Tragedy of the Jews of Slovakia

N Swedish interventions in the tragedy J of the Jews of Slovakia Denisa Nešťáková and Eduard Nižňanský Abstract • This article describes a largely unknown Swedish effort to intervene in deportations of Jews of Slovakia between 1942 and 1944. Swedish officials and religious leaders used their diplo- matic correspondence with the Slovak government to extract some Jewish individuals and later on the whole Jewish community of Slovakia from deportations by their government and eventually by German officials. Despite the efforts of the Swedish Royal Consulate in Bratislava, the Swedish arch bishop, Erling Eidem, and the Slovak consul, Bohumil Pissko, in Stockholm, and despite the acts taken by some Slovak ministries, the Slovak officials, including the president of the Slovak Republic, Jozef Tiso, revoked further negotiations in the autumn of 1944. However, the negotiations between Slovakia and Sweden created a scope for actions to protect some Jewish individuals which were doomed to failure because of the political situation. Nevertheless, this plan and the previous diplomatic interventions are significant for a description of the almost unknown Swedish and Slovak efforts to save the Jews of Slovakia. Repeated Swedish offers to take in Jewish individuals and later the whole community could well have prepared the way for larger rescues. These never occurred, given the Slovak interest in deporting their own Jewish citizens and later the German occupation of Slovakia. Research on Sweden’s attempts the ‘opening’ of the archives in some post- to assist Jews communist countries and new scholars tak- In view of the abundance of studies of the ing up this particular topic have significantly Holocaust, the absence of major scholarly improved research opportunities.