Teacher's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the History of the Holocaust II

UNDERSTANDING THE HISTORY OF THE HOLOCAUST II Jewish Resistance, Miracles & Righteous Gentiles n the first Morasha shiur on the Holocaust, we developed a rudimentary Iunderstanding of the horrors of the Holocaust and its irrevocable impact on the Jewish people. We will now turn our attention to some of the glimmers of hope that appeared during those dark days. It is important to dispel the myth that Jews went to their deaths passively, “like lambs to the slaughter.” For reasons that will be mentioned below, Jewish resistance was often spiritual rather than physical; the manner in which they retained their human spirit, and even their Jewish spirit, demonstrates strength of character that we can barely imagine. Most of the stories of Jewish courage were lost with their heroes. Some have been passed on to us. It is our duty to remember these stories, and internalize their messages. Furthermore, while the Holocaust was a time of unimaginable suffering and darkness for the Jewish people, many of those who survived (and even those who ultimately did not) experienced moments of salvation that were nothing short of miraculous. Stretched beyond the limits of physical endurance and facing the merciless, overwhelming brutality of the Nazis, many Jews found that their lives were saved in the most improbable ways. The history of the Holocaust is replete with such miracles, evidence that God was still with us even during that time of suffering. Finally, it is important to mention some of the non-Jewish heroes who risked their own lives to save Jews from certain death. Even at a time in history when the entire world seemed to have turned against the Jewish people, there were still isolated individuals who demonstrated both mercy and courage by extending themselves to save Jews. -

Joan Campion. in the Lion's Mouth: Gisi Fleischmann and the Jewish Fight for Survival

Gorbachev period) that, "As a liberal progressive reformer, and friend of the West, Gorbachev is ... a figment of Western imagination." One need not see Gorbachev as a friend or a liberal, of course, to understand that he in- tended from the outset to change the USSR in fundamental ways. To be sure, there are some highlights to this book. Chapter 4 by Gerhard Wettig (of the Bundesinstitut fiir Ostwissenschaftliche und Internationale Studien) discusses important conceptual distinctions made by the Soviets in their view of East-West relations. Finn Sollie, of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in Norway, provides a balanced and insightful consideration of Northern Flank security issues. This is not the book it could have been given the talented people involved in the conferences that led to such a volume. Given the timing of its produc- tion (during the first two years of Gorbachev's rule), the editors should have done much more to seek up-dated and more in-depth analyses from the contributors. As it stands, Cline, Miller and Kanet have given us a foot- note in the record of a waning Cold War. Daniel N. Nelson University of Kentucky Joan Campion. In the Lion's Mouth: Gisi Fleischmann and the Jewish Fight for Survival. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987. xii, 152 pp. $24.50 (cloth), $12.75 (paper). The immense accumulation of scholarship on the Holocaust and World War II made possible the emergence of a new genre of literature portraying heroic figures engaged in rescue work in terror-ridden Nazi Europe. The last decade has seen the publication of a spate of books including the sagas of Raoul Wallenberg, Hanna Senesh and Janusz Korczak, drawing on extensive source material as well as previous literature. -

Epoch of the Messiah by Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman

Epoch of the Messiah As Distributed By S. GOLDMAN - OTZAR HASEFARIM Inc. 33 Canal Street, New York, N.Y.1OOO2 Importers and Publishers of Hebrew Books Copyright 1985 by Rabbi E.S. Wasserman 851 North Kings Rd. Los Angeles, Calif. 90069 Rabbi Elchonon Bunim Wasserman, zt'l A Brief Biographical Sketch Reb Elchonon, zt'l, was born in 1874 in Birz, Lithuania. Circa 1889 his parents moved to Boisk, Latvia, at that time the Rabbinical Seat of Rabbi Cook, olov hasholom. From there he went to Telz where he studied under the illustrious gaonim, Rabbi Eliezer Gordon, zt'l and Rabbi Shimon Shkop, zt'l. In Telz, he was noted for his unusual diligence and profound mind. After many years of intensive study in Telz, he went to Volozin to become a disciple of the great Reb Chaim Brisker who was Rosh yeshivah of Volozin at that time. In 1898, he married the daughter of one of the leading sages of the day, Rabbi Meir Atlas, zt'l, who was then the Rabbi of Salant. Then came a period which impressed itself indelibly on the rest of his life. It began in 1906 when he went to Radin, the home of his master, the world-renowned Chofetz Chaim, zt'l where he studied until 1908 in the Kollel Kodshim. The Chofetz Chaim had founded this select institution for the future leaders of Israel. During the year 1908-1909, Rav Elchonon, together with the gaon Rabbi Yoel Baranchick zt'l started a yeshivah in Amsislav, Russia. In 1910, he accepted a call to become a rosh yeshivah in Brisk, the home of his teacher, Rabbi Chaim, zt'l. -

Jerusalemhem Volume 91, February 2020

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 91, February 2020 “Remembering the Holocaust, Fighting Antisemitism” The Fifth World Holocaust Forum at Yad Vashem (pp. 2-7) Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 91, Adar 5781, February 2020 “Remembering the Holocaust, Published by: Fighting Antisemitism” ■ Contents Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau International Holocaust Remembrance Day ■ 2-12 Chancellor of the Council: Dr. Moshe Kantor “Remembering the Holocaust, Vice Chairman of the Council: Dr. Yitzhak Arad Fighting Antisemitism” ■ 2-7 Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev The Fifth World Holocaust Forum at Yad Vashem Director General: Dorit Novak Tackling Antisemitism Through Holocaust Head of the International Institute for Holocaust ■ 8-9 Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Education for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman Survivors: Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Faces of Life After the Holocaust ■ 10-11 Academic Advisor: Joining with Facebook to Remember Prof. Yehuda Bauer Holocaust Victims ■ 12 Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: ■ 13 Shmuel Aboav, Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Treasures from the Collections Dr. David Breakstone, Abraham Duvdevani, Love Letter from Auschwitz ■ 14-15 Erez Eshel, Prof. Boleslaw (Bolek) Goldman, Moshe Ha-Elion, Adv. Shlomit Kasirer, Education ■ 16-17 Yehiel Leket, Adv. Tamar Peled Amir, Graduate Spotlight ■ 16-17 Avner Shalev, Baruch Shub, Dalit Stauber, Dr. Zehava Tanne, Dr. Laurence Weinbaum, Tamara Vershitskaya, Belarus Adv. Shoshana Weinshall, Dudi Zilbershlag New Online Course: Chosen Issues in Holocaust History ■ 17 THE MAGAZINE Online Exhibition: Editor-in-Chief: Iris Rosenberg Children in the Holocaust ■ 18-19 Managing Editor: Leah Goldstein Editorial Board: Research ■ 20-23 Simmy Allen The Holocaust in the Soviet Union Tal Ben-Ezra ■ 20-21 Deborah Berman in Real Time Marisa Fine International Book Prize Winners 2019 ■ 21 Dana Porath Lilach Tamir-Itach Yad Vashem Studies: The Cutting Edge of Dana Weiler-Polak Holocaust Research ■ 22-23 ■ Susan Weisberg At the invitation of the President of the Fellows Corner: Dr. -

Gadol Beyisrael Hagaon Hakadosh Harav Chaim Michoel Dov

Eved Hashem – Gadol BeYisrael HaGaon HaKadosh HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L (4. Cheshvan 5664/ 25. Oktober 1903, Debrecen, Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia – 6 Kislev 5718/ 29. November 1957, Mount Kisco, New York) Евед ХаШем – Гадоль БеИсраэль ХаГаон ХаКадош ХаРав Хаим-Михаэль-Дов Вайсмандель; Klenot medzi Klal Yisroel, Veľký Muž, Bojovník, Veľký Tzaddik, vynikajúci Talmid Chacham. Takýto človek príde na svet iba raz za pár storočí. „Je to Hrdina všetkých Židovských generácií – ale aj pre každého, kto potrebuje príklad odvážneho človeka, aby sa pozrel, kedy je potrebná pomoc pre tých, ktorí sú prenasledovaní a ohrození zničením v dnešnom svete.“ HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L, je najväčší Hrdina obdobia Holokaustu. Jeho nadľudské úsilie o záchranu tisícov ľudí od smrti, ale tiež pokúsiť sa zastaviť Holokaust v priebehu vojny predstavuje jeden z najpozoruhodnejších príkladov Židovskej histórie úplného odhodlania a obete za účelom záchrany Židov. Nesnažil sa zachrániť iba niektorých Židov, ale všetkých. Ctil a bojoval za každý Židovský život a smútil za každou dušou, ktorú nemohol zachrániť. Nadľudské úsilie Rebeho Michoela Ber Weissmandla oddialilo deportácie viac ako 30 000 Židov na Slovensku o dva roky. Zohral vedúcu úlohu pri záchrane tisícov životov v Maďarsku, keď neúnavne pracoval na zverejňovaní „Osvienčimských protokolov“ o nacistických krutostiach a genocíde, aby „prebudil“ medzinárodné spoločenstvo. V konečnom dôsledku to ukončilo deportácie v Maďarsku a ušetrilo desiatky tisíc životov maďarských Židov. Reb Michoel Ber Weissmandel bol absolútne nebojácny. Avšak, jeho nebojácnosť sa nenarodila z odvahy, ale zo strachu ... neba. Každý deň, až do svojej smrti ho ťažil smútok pre milióny, ktorí nemohli byť spasení. 1 „Prosím, seriózne študujte Tóru,“ povedal HaRav Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandel ZTVK "L svojim študentom, "spomína Rav Spitzer. -

The Lithuanian Jewish Community of Telšiai

The Lithuanian Jewish Community of Telšiai By Philip S. Shapiro1 Introduction This work had its genesis in an initiative of the “Alka” Samogitian Museum, which has undertaken projects to recover for Lithuanians the true history of the Jews who lived side-by-side with their ancestors. Several years ago, the Museum received a copy of the 500-plus-page “yizkor” (memorial) book for the Jewish community of Telšiai,2 which was printed in 1984.3 The yizkor book is a collection of facts and personal memories of those who had lived in Telšiai before or at the beginning of the Second World War. Most of the articles are written in Hebrew or Yiddish, but the Museum was determined to unlock the information that the book contained. Without any external prompting, the Museum embarked upon an ambitious project to create a Lithuanian version of The Telshe Book. As part of that project, the Museum organized this conference to discuss The Telshe Book and the Jewish community of Telšiai. This project is of great importance to Lithuania. Since Jews constituted about half of the population of most towns in provincial Lithuania in the 19th Century, a Lithuanian translation of the book will not only give Lithuanian readers a view of Jewish life in Telšiai but also a better knowledge of the town’s history, which is our common heritage. The first part of this article discusses my grandfather, Dov Ber Shapiro, who was born in 1883 in Kamajai, in the Rokiškis region, and attended the Telshe Yeshiva before emigrating in 1903 to the United States, where he was known as “Benjamin” Shapiro. -

Thesis Front Matter

Memories of Youth: Slovak Jewish Holocaust Survivors and the Nováky Labor Camp Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Antony Polonsky & Joanna B. Michlic, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Karen Spira May 2011 Copyright by Karen Spira ! 2011 ABSTRACT Memories of Youth: Slovak Jewish Holocaust Survivors and the Nováky Labor Camp A thesis presented to the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Karen Spira The fate of Jewish children and families is one of the understudied social aspects of the Holocaust. This thesis aims to fill in the lacuna by examining the intersection of Jewish youth and families, labor camps, and the Holocaust in Slovakia primarily using oral testimonies. Slovak Jewish youth survivors gave the testimonies to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, Israel. Utilizing methodology for examining children during the Holocaust and the use of testimonies in historical writing, this thesis reveals the reaction of Slovak Jewish youth to anti-Jewish legislation and the Holocaust. This project contributes primary source based research to the historical record on the Holocaust in Slovakia, the Nováky labor camp, and the fate of Jewish youth. The testimonies reveal Jewish daily life in pre-war Czechoslovakia, how the youth understood the rise in antisemitism, and how their families ultimately survived the Holocaust. Through an examination of the Nováky labor camp, we learn how Jewish families and communities were able to remain together throughout the war, maintain Jewish life, and how they understood the policies and actions enacted upon them. -

Y University Library

Y university library Fortuno≠ Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies professor timothy snyder Advisor PO Box 208240 New Haven CT 06520-8240 t 203 432-1879 web.library.yale.edu/testimonies Episode 6 — Renee Hartman Episode Notes by Dr. Samuel Kassow Renee Glassner Hartman was born in 1933 in Bratislava (Pressburg in German, Poszonyi in Hungarian). She had a younger sister, Herta, born in 1935. Their parents, like Herta, were deaF. Their father was a jeweler. This is the story oF two young children who were raised in a loving, religiously observant home and who experienced the traumatic and sudden destruction oF their childhood, the loss oF their parents, and their own deportation to the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, from which they were liberated by the British in 1945. As they struggled to stay alive, Renee and Herta were inseparable. No matter how depressed and distraught she became, Renee never forgot that her younger sister, unable to hear, totally depended on her. Together they survived a long nightmare that included betrayal, physical violence, liFe-threatening disease, and hunger. During the time when Renee and Herta were born, the Jews oF Bratislava lived in relative peace and security. BeFore World War I, most Jews in Bratislava had spoken Magyar or German (German was the language in Renee’s home). Between the wars they also had to learn Slovak as Bratislava, formerly under Hungarian administration, became part oF the new Czechoslovak state, which was founded in 1918. Under the leadership oF President Thomas Masaryk, Czechoslovakia was a democracy, and somewhat more prosperous than countries like Poland and Hungary. -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp. -

Holocaust Responsa in the Kovno Ghetto 1941-44 by Ephraim Kaye

1 WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 13, 1999 AFTERNOON SESSION A 14:00-15:30 Holocaust Responsa in the Kovno Ghetto 1941-44 by Ephraim Kaye Goals of the Unit 1. To describe the lives of the Jews in the Kovno Ghetto as reflected in Rabbi Ephraim Oshry's responsa. 2. To illuminate several fateful issues that Orthodox Jews confronted in their struggle for Jewish survival in the ghetto, at a time when escape still seemed possible and hope for deliverance still flickered. 3. To engage students in discussion of these issues so they may arrive at their own answers. The main problem treated in this unit: How did Orthodox Jews contend with existential questions in the ghetto with the assistance and encouragement of Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, as reflected in his halakhic rulings? Phases of the Unit 1. Introduction: the teacher describes the nature of responsa literature and shows how it may be used as a historical source – generally, and in the specific context of Holocaust studies. 2. The students are divided into three groups, each assigned one of the halakhic problems taken up by Rabbi Oshry. A uniform eleven-item "worksheet" is given to all the groups. The items provide a foundation for analysis of the historical dimension of the issue. Each student is also given a "source sheet" that helps him or her deal with the issue at hand (a sheet with sources upon which R. Oshry based his halakhic decisions.) 3. Each group fills in each section of the worksheet and attempts to formulate a response to the question that it was given. -

Teacher Meaning-Making at a Jewish Heritage Museum David Russell

Museum-Based Teacher Education: Teacher Meaning-Making at a Jewish Heritage Museum David Russell Goldberg Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 David Russell Goldberg All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT MUSEUM-BASED TEACHER EDUCATION: TEACHER MEANING-MAKING AT A JEWISH HERITAGE MUSEUM David Russell Goldberg This study answers the question of what meanings teacher-participants make in Holocaust professional development at a Jewish heritage museum in a mandate state. By understanding these meanings, the educational community can better understand how a particular context and approach influences teacher meaning-making and the ways in which museum teacher education programs shape the learning of participants. Meaning- making is a process of interpretation and understanding experiences in ways that make sense to each individual teacher. Meanings that are formed may impact teachers’ pedagogic interpretation of the Holocaust, which may in turn shape their instructional practices. This instrumental case study used multiple interviews, observations, surveys and documents to explore the meanings teachers make about the Holocaust from participation in Holocaust professional development at a Jewish heritage museum. Participants in the study included nine teachers from public schools and private Jewish schools and two professional developers from the Museum. Each participant was interviewed three times, and six different professional development programs were observed over a period of six months. Programs typically lasted from one to six days and included a presentation by museum staff, Holocaust experts, and survivors. At any museum, each representation of the Holocaust conveys particular messages and mediates Holocaust history through a particular lens. -

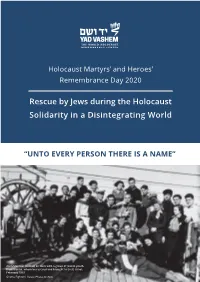

Rescue by Jews During the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World

Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day 2020 Rescue by Jews during the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World “UNTO EVERY PERSON THERE IS A NAME” Aron Menczer (center) on deck with a group of Jewish youth from Vienna, whom he rescued and brought to Eretz Israel, February 1939 Ghetto Fighters’ House Photo Archive Jerusalem, Nissan 5780 April 2020 “Unto Every Person There Is A Name” Public Recitation of Names of Holocaust Victims in Israel and Abroad on Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day “Unto every person there is a name, given to him by God and by his parents”, wrote the Israeli poetess Zelda. Every single victim of the Holocaust had a name. The vast number of Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust – some six million men, women and children - is beyond human comprehension. We are therefore liable to lose sight of the fact that each life that was brutally ended belonged to an individual, a human being endowed with feelings, thoughts, ideas and dreams whose entire world was destroyed, and whose future was erased. The annual recitation of names of victims on Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day is one way of posthumously restoring the victims’ names, of commemorating them as individuals. We seek in this manner to honor the memory of the victims, to grapple with the enormity of the murder, and to combat Holocaust denial and distortion. This year marks the 31st anniversary of the global Shoah memorial initiative “Unto Every Person There Is A Name”, held annually under the auspices of the President of the State of Israel.