17. Popularity/Prestige

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

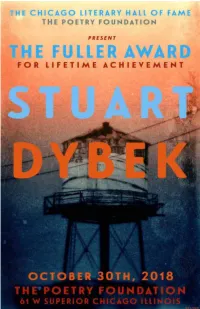

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

The Failure of Sympathy in the Recent Works of J.M. Coetzee

The failure of sympathy in the recent works of JM Coetzee Warwick Ian Shapcott A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts (Research) School of English University of New South Wales July 2006 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed ......... Date ........................ ..~~.l.~.l~.7 ......................... COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Short Stories in the Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 430 231 CS 216 694 AUTHOR Hamilton, Carole L., Ed.; Kratzke, Peter, Ed. TITLE Short Stories in the Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0399-5 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 219p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03995-0015: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *English Instruction; Literature Appreciation; *Reader Text Relationship; Secondary Education; *Short Stories IDENTIFIERS *Response to Literature ABSTRACT Examining how teachers help students respond to short fiction, this book presents 25 essays that look closely at "teachable" short stories by a diverse group of classic and contemporary writers. The approaches shared by the contributors move from readers' first personal connections to a story, through a growing facility with the structure of stories and the perception of their varied cultural contexts, to a refined and discriminating sense of taste in short fiction. After a foreword ("What Is a Short Story and How Do We Teach It?"), essays in the book are: (1) "Shared Weight: Tim O'Brien's 'The Things They Carried'" (Susanne Rubenstein); (2) "Being People Together: Toni Cade Bambara's 'Raymond's Run'" (Janet Ellen Kaufman); (3) "Destruct to Instruct: 'Teaching' Graham Greene's 'The Destructors'" (Sara R. Joranko); (4) "Zora Neale Hurston's 'How It Feels to Be Colored Me': A Writing and Self-Discovery Process" (Judy L. Isaksen); (5) "Forcing Readers to Read Carefully: William Carlos Williams's 'The Use of Force'" (Charles E. -

The Drink Tank Sixth Annual Giant Sized [email protected]: James Bacon & Chris Garcia

The Drink Tank Sixth Annual Giant Sized Annual [email protected] Editors: James Bacon & Chris Garcia A Noise from the Wind Stephen Baxter had got me through the what he’ll be doing. I first heard of Stephen Baxter from Jay night. So, this is the least Giant Giant Sized Crasdan. It was a night like any other, sitting in I remember reading Ring that next Annual of The Drink Tank, but still, I love it! a room with a mostly naked former ballerina afternoon when I should have been at class. I Dedicated to Mr. Stephen Baxter. It won’t cover who was in the middle of what was probably finished it in less than 24 hours and it was such everything, but it’s a look at Baxter’s oevre and her fifth overdose in as many months. This was a blast. I wasn’t the big fan at that moment, the effect he’s had on his readers. I want to what we were dealing with on a daily basis back though I loved the novel. I had to reread it, thank Claire Brialey, M Crasdan, Jay Crasdan, then. SaBean had been at it again, and this time, and then grabbed a copy of Anti-Ice a couple Liam Proven, James Bacon, Rick and Elsa for it was up to me and Jay to clean up the mess. of days later. Perhaps difficult times made Ring everything! I had a blast with this one! Luckily, we were practiced by this point. Bottles into an excellent escape from the moment, and of water, damp washcloths, the 9 and the first something like a month later I got into it again, 1 dialed just in case things took a turn for the and then it hit. -

Historical Fiction

Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Library, Arts & Culture To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818-548-2021 New Titles in the Collection — Spring 2021 Access the complete list at: https://www.glendaleca.gov/government/departments/library-arts-culture/services/book-groups-kits American Dirt by Jeannine Cummins When Lydia Perez, who runs a book store in Acapulco, Mexico, and her son Luca are threatened they flee, with countless other Mexicans and Central Americans, to illegally cross the border into the United States. This page- turning novel with its in-the-news presence, believable characters and excellent reviews was overshadowed by a public conversation about whether the author practiced cultural appropriation by writing a story which might have been have been best told by a writer who is Latinx. Multicultural Fiction. 400 pages The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson Kentucky during the Depression is the setting of this appealing historical fiction title about the federally funded pack-horse librarians who delivered books to poverty-stricken people living in the back woods of the Appalachian Mountains. Librarian Cussy Mary Carter is a 19-year-old who lives in Troublesome Creek, Kentucky with her father and must contend not only with riding a mule in treacherous terrain to deliver books, but also with the discrimination she suffers because she has blue skin, the result of a rare genetic condition. Both personable and dedicated, Cussy is a sympathetic character and the hardships that she and the others suffer in rural Kentucky will keep readers engaged. -

Lunar Sourcebook : a User's Guide to the Moon

3 THE LUNAR ENVIRONMENT David Vaniman, Robert Reedy, Grant Heiken, Gary Olhoeft, and Wendell Mendell 3.1. EARTH AND MOON COMPARED fluctuations, low gravity, and the virtual absence of any atmosphere. Other environmental factors are not The differences between the Earth and Moon so evident. Of these the most important is ionizing appear clearly in comparisons of their physical radiation, and much of this chapter is devoted to the characteristics (Table 3.1). The Moon is indeed an details of solar and cosmic radiation that constantly alien environment. While these differences may bombard the Moon. Of lesser importance, but appear to be of only academic interest, as a measure necessary to evaluate, are the hazards from of the Moon’s “abnormality,” it is important to keep in micrometeoroid bombardment, the nuisance of mind that some of the differences also provide unique electrostatically charged lunar dust, and alien lighting opportunities for using the lunar environment and its conditions without familiar visual clues. To introduce resources in future space exploration. these problems, it is appropriate to begin with a Despite these differences, there are strong bonds human viewpoint—the Apollo astronauts’ impressions between the Earth and Moon. Tidal resonance of environmental factors that govern the sensations of between Earth and Moon locks the Moon’s rotation working on the Moon. with one face (the “nearside”) always toward Earth, the other (the “farside”) always hidden from Earth. 3.2. THE ASTRONAUT EXPERIENCE The lunar farside is therefore totally shielded from the Earth’s electromagnetic noise and is—electro- Working within a self-contained spacesuit is a magnetically at least—probably the quietest location requirement for both survival and personal mobility in our part of the solar system. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

Doğaya 'Can' Katıyor

1 Hafıza Sanatı Metis Kitap’tan SAYI: 98 YIL: 2 Olga Tokarczuk doğaya ‘can’ katıyor 2 4 Olga Tokarczuk doğanın hesabını soruyor! 11 17 Yasanın üzerinde tepinmeye çalışan 'Ne güzel bir dünya bu, iyi ki geldim' insan hakkında Özge Uysal Doğuş Sarpkaya 25 20 'Haremin son kızı' Emine Adalet'in O, Antonin Artaud ilginç hayatı Gökhan Akçura Emek Erez 27 33 George Saunders’ın 'Aralığın Onu' Nêrinek li ser romana Mîrzayê Reben Bülent Ayyıldız Hasan Polat 3 Sayı: 98 | Şubat 2020 Merhaba, Yayın Sahibi Bu sayımızda 2018 Nobel Edebiyat Ödülü sahibi Olga AND Gazetecilik ve Yayıncılık, Tokarczuk'u kapağımıza taşıdık. Tokarczuk'un son romanı Sür Pulluğunu Ölülerin Kemikleri Üzerinde 2006 ve 2016 San. ve Tic. A.Ş. adına yıllarında Lehçe çeviride iki önemli ödüle layık görülmüş Neşe Vedat Zencir Taluy'un çevirisiyle Timaş Yayınları tarafından yayımlandı. Tokarczuk, temelde 'meta' olan doğa ve hayvanları, tekrar 'canlı' ve 'özne' konumuna getiren, kiliseye karşı eleştirel bir Genel Yayın Yönetmeni cümle kurabilen, otoriterinin gözünde yok sayılan Janina'nın yeniden varoluş ve yaşamı anlamlandırma çabası olarak olarak Ali Duran Topuz şimdiden modern edebiyatın en özel örneklerinden olacak bir metin olarak okurunu bekliyor. Erhan Yılmaz yazdı. İcra Kurulu Başkanı ve Tokarczuk, bu romanıyla birlikte okurlarının romandaki Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü her bir ögenin anlamı üzerine bir çevirmen titizliğiyle eğilip semboller, feminist mesajları ve insan odaklı dünya görüşünün Ömer Araz batışı üzerine daha çok düşünmesini talep ediyor. Özge Uysal'ın kaleminden... Yazı İşleri Müdürü George Saunders'ın öykü derlemesi olan "Aralığın Onu", sıradan Anıl Mert Özsoy insanın deneyimine odaklanarak kişisel başarısızlıkların, düş kırıklıklarının, baskının ve umutla beslenen sınıfsal kaygıların insanı nasıl bir saplantılar labirentine soktuğunu gösteriyor. -

Holiday Books from Crawford Doyle

20 Classic Rare Books for Holiday Gifts from Crawford Doyle Here are some nice books which would make thoughtful presents. Take a look and if you're interested, call us at 212 289 2345 or send us an Email at [email protected]. Thanks for your interest. --John Doyle Blue Nights by Joan Didion (Signed - $100) Joan Didion, the noted American journalist and writer of novels, screenplays, and autobiographical works, is best known for her literary journalism and memoirs. She suddenly lost her husband, the author John Gregory Dunne, to a heart attack in 2003, impelling her to write a wrenching memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, describing the event. Two years later, she lost her only daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, to a sudden illness. In Blue Nights, she describes her desperate efforts to cope with and survive this tragedy. New York: Knopf, 2011. First Edition. A fine copy bound in black cloth with silver spine lettering in an fine dustwrapper. The author has signed this copy on the title page. The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway ($150) This comprehensive Hemingway edition includes all of the stories from The First Forty Nine plus fourteen stories published subsequently, seven never- before-published short stories and three extended scenes from unfinished novels. This is the definitive collection of the author's short stories. Hemingway's most beloved classics are here, including "The Snows of Kilimanjaro," "Hills Like White Elephants," and "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place." Readers will delight in the seven new tales published here for the first time. New York: Scribner, 1987. -

F14 US Catalogue.Pdf

HARPERAUDIO You Are Not Special CD ...And Other Encouragements Jr. McCullough, David Summary A profound expansion of David McCullough, Jr.’s popular commencement speech—a call to arms against a prevailing, narrow, conception of success viewed by millions on YouTube—You Are (Not) Special is a love letter to students and parents as well as a guide to a truly fulfilling, happy life Children today, says David McCullough—high school English teacher, father of four, and HarperAudio 9780062338280 son and namesake of the famous historian—are being encouraged to sacrifice On Sale Date: 4/22/14 passionate engagement with life for specious notions of success. The intense pressure $43.50 Can. to excel discourages kids from taking chances, failing, and learning empathy and self CDAudio confidence from those failures. Carton Qty: 20 Announced 1st Print: 5K In You Are (Not) Special, McCullough elaborates on his nowfamous speech exploring Family & Relationships / how, for what purpose, and for whose sake, we’re raising our kids. With wry, Parenting affectionate humor, McCullough takes on hovering parents, ineffectual schools, FAM034000 professional college prep, electronic distractions, club sports, and generally the 6.340 oz Wt 180g Wt manifestations, and the applications and consequences of privilege. By acknowledging that the world is indifferent to them, McCullough takes pressure off of students to be extraordinary achievers and instead exhorts them to roll up their sleeves and do something useful with their advantages. Author Bio David McCullough started teaching English in 1986. He has appeared on and/or done interviews for the following outlets: Fox 25 News, CNN, NBC Nightly News, CBS This Morning, NPR’s All Things Considered, ABC News, Boston Herald, Boston Globe, Wellesley Townsman, Montreal radio, Vancouver radio, Madison, WI, radio, Time Magazine and Epoca (Brazilian magazine).