SUMMER READING 2019 11Th and 12Th Grades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARSEC Meeting Schedule Geis on R.O.D. Davin on Popularity Ferrier on Books

PARSEC Meeting Schedule April 2005 Date: April 9th 2005 - 2 PM Topic: Dr. Eric Davin presents "WEIRD SISTERS: Women and Weird Tales Magazine, 1923-1954." Location: Allegheny Branch of Carnegie Library The Newsletter of PARSEC • April 2005 • Issue 229 May 2005 Geis on R.O.D. Ferrier on Books Date: May 14th 2005 - 2 PM Topic: TBA Davin on Popularity Location: TBA SIGMA June 2005 Date: June 11th 2005 - 2 PM Topic: TBA Location: TBA The Carnegie Library. Allegheny Regional is approximately 1 mile north of Downtown Pittsburgh. Situated in Allegheny Center in the Central North Side neighborhood, Allegheny Regional lies just behind Allegheny Center immediately beside the old Buhl Planetarium. For Directions please refer to the Parsec web site: http://www.parsec-sff.org/meet.html PARSEC The Pittsburgh Area’s Premiere Science-Fiction Organization P.O. Box 3681, Pittsburgh, PA 15230-3681 President - Kevin Geiselman Vice President - Sarah Wade-Smith Treasurer - Greg Armstrong Secretary - Joan Fisher Commentator - Ann Cecil Website: http://www.parsec-sff.org Meetings - Second Saturday of every month. Dues: $10 full member, $2 Supporting member Sigma is edited by David Brody Send article submissions to: [email protected] View From the Top Filk News The President’s Column - Kevin Geiselman Randy Hoffman will be performing in the Acoustic Last week I received a call from CMU concerning Songwriters Showcase at the Starlite Lounge in Blawnox on the a help desk job. Hoody-hoo! An opportunity to leave evening of Saturday, May 7. the underpaid, dead-end job I happen to be in right Confluence regular Pete Grubbs will be one of the acts per- now. -

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Alphabetical list of Authors Clonmel Library Douglas Adams Kazuo Ishiguro Clonmel Library Issac Asimov PD James Ray Bradbury Robert Jordan Terry Brooks Kate Jacoby RecommendedRecommended Trudi Canavan Ursala K. Le Guin Arthur C Clarke George Orwell Susanna Clarke Anne McCaffery ReadingReading Philip K. Dick George RR Martin David Eddings Mervyn Peake Raymond E. Feist Terry Pratchett American Gods Philip Pullman Neil Gaiman Brandon Sanderson David Gemmell JRR Tolkein Terry Goodkind Jules Verne Robert A. HeinLein Kurt Vonnegut FantasyFantasy && Frank Herbert T.H. White Robin Hobb Aldous Huxley Clonmel Library ScienceScience FictionFiction Opening Hours & Contact Details Monday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Tuesday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Wednesday: 9.30 am – 8.00 pm Thursday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Friday: 9.30 am – 1pm & 2pm - 5pm Saturday: 10.00 am – 1pm & 2pm-5pm Phone: (052) 6124545 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.tipperarylibraries.ie/clonmel 11 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea AnAn IntroductionIntroduction Jules Verne First published 1869 toto FantasyFantasy French naturalist Dr. Aronnax embarks on an expedition to hunt down a sea monster, only to discover instead the && ScienceScience FictionFiction Nautilus, a remarkable submarine built by the enigmatic Captain Nemo. Together Nemo and Aronnax explore the antasy is a genre that uses magic and other supernatural forms underwater marvels, undergo a transcendent experience as a primary element of plot, theme, and/or setting. Fantasy is amongst the ruins of Atlantis, and plant a -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Summer Reading 2021

Shady Side Academy Senior School Summer Reading 2021 This summer, you will have the opportunity to read two (2) books before returning to classes in the fall. You will read one book to be discussed in your Fall term English class, and one to be discussed with your Advisory group. English Book: See the list below for your Form’s text. You should be prepared to discuss it in your English class, so be sure to read and annotate it in such a way that you have some knowledge of it in your working memory when you are back on campus; your fall-term English teacher will give you more details about what you will do with that knowledge when you meet him/her on the first day of classes. Above all, enjoy the reading! Advisory Book: All Form III students will read the same book; students in Forms IV, V, and VI can find their texts listed below under their individual advisor’s name. You should plan on being prepared to discuss this book with your advisory group during an extended Designated Rooms meeting during the first week of classes. Your advisor may also ask you to write up something on your text in preparation for that discussion session, perhaps in a Google document of some kind; stay tuned for details when the opening of classes draws nearer. In the meantime, please enjoy the selection your advisor has made. View the Table of Contents on the next page to see the assigned books per form and per advisory. If you are purchasing books locally, please consider supporting the following independent bookstores: City of Asylum Bookstore, Riverstone Books, -

COLORED VINYL Merchant Record Store, and the Influential Radio Show/Podcast BTS Radio

UBIQUITY RECORDS PRESENTS SAVE THE MUSIC 12” NO. 3 - BTS EXCLUSIVES FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 04/16/2011 feature on Gilles Peterson’s “Brownswood Save the Music – is a Electric” comp and a remix for Solar Bears Planet compilation for Record Mu debut in the last 12 months. Jed and Lucia drop a brand new sunny-styled chill wave-goes-Brazil cut Store Day that called “This is Why.”. features exclusive new music from: AM, A1. S.Maharba featuring Jed and Princess Superstar, Lucia - So Much Skin The Incredible Tabla A2. Letherette – Roses Band, S.Maharba, Letherette, B1. Dibiase – Cybertron Dibiase, Jed & Lucia, NOMO, Shawn B2. Jed and Lucia – This is Why Lee, Magnetite, and a re-issued folky funk joint from Pats People. The music from the limited edition compilation CD is LIMITED EDITION spread across 3 limited edition (500 of each only!), hand-numbered, 12” singles. HAND NUMBERED The track list for each of the 12”s was put together with the help of our musical friends Shawn Lee, The Groove COLORED VINYL Merchant record store, and the influential radio show/podcast BTS Radio. 500 COPIES ONLY Since 2003 Andrew Meza’s BTS radio has presented 12 - CATALOG UBR11289-1 some of the most original and progressive music podcasts LIST PRICE: $10.97 and is credited with spearheading the worldwide beat 12 BOX LOT: 50 movement, and introducing acts like Flying Lotus and VINYL IS NON-RETURNABLE Hudson Mohawke. BTS-partner Charles Munka designed FOR FANS OF: the album and 12” art for Save the Music. -

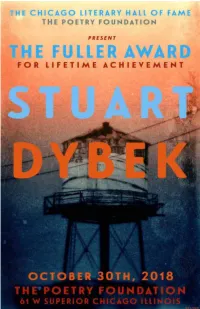

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

The Failure of Sympathy in the Recent Works of J.M. Coetzee

The failure of sympathy in the recent works of JM Coetzee Warwick Ian Shapcott A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts (Research) School of English University of New South Wales July 2006 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed ......... Date ........................ ..~~.l.~.l~.7 ......................... COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

February 2021

F e b r u a r y 2 0 2 1 V o l u m e 1 2 I s s u e 2 BETWEEN THE PAGES Huntsville Public Library Monthly Newsletter Learn a New Language with the Pronunciator App! BY JOSH SABO, IT SERVICES COORDINATOR According to Business Insider, 80% of people fail to keep their New Year’s resolutions by the second week in February. If you are one of the lucky few who make it further, congratulations! However, if you are like most of us who have already lost the battle of self-improvement, do not fret! Learning a new language is an excellent way to fulfill your resolution. The Huntsville Public Library offers free access to a language learning tool called Pronunciator! The app offers courses for over 163 different languages and users can personalize it to fit their needs. There are several different daily lessons, a main course, and learning guides. It's very user-friendly and can be accessed at the library or from home on any device with an internet connection. Here's how: 1) Go to www.myhuntsvillelibrary.com and scroll down to near the bottom of the homepage. Click the Pronunciator link below the Pronunciator icon. 2) Next, you can either register for an account to track your progress or simply click ‘instant access’ to use Pronunciator without saving or tracking your progress. 3) If you want to register an account, enter a valid email address to use as your username. 1219 13th Street Then choose a password. Huntsville, TX 77340 @huntsvillelib (936) 291-5472 4) Now you can access Pronunciator! Monday-Friday Huntsville_Public_Library 10 a.m. -

A Study of Microtones in Pop Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Chadwin, Daniel James Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music Original Citation Chadwin, Daniel James (2019) Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34977/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Applying microtonality to pop songwriting A study of microtones in pop music Daniel James Chadwin Student number: 1568815 A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Huddersfield May 2019 1 Abstract While temperament and expanded tunings have not been widely adopted by pop and rock musicians historically speaking, there has recently been an increased interest in microtones from modern artists and in online discussion. -

Still Drinking

Vol. 8 april2016 — issue 4 INSIDE: slow future - still drinking - line out: LUCA - priced outta b/cs - YOU’RE NOT PUNK & I’M TELLING EVERYONE - trauma Tuesday still poetry - Ask creepy horse - pedal pushing - QUITTING COFFEE - RICKSHAW HEART - record reviews concert calendar Priced outta b/cs I moved to College Station ten years ago. My family was somewhat unceremoni- ously kicked out of Seattle and needed somewhere to go. My wife found a job at Texas A&M so we loaded up the U-Haul and drove it 2000 979Represent is a local magazine miles in the July sun. We weren’t chased out of the for the discerning dirtbag. Emerald City because of crime or anything improper, we were chased out by the drastic increase in the cost of living and the continued stagnation of mid- Editorial bored dle class wages. We conducted a national search Kelly Minnis - Kevin Still for college towns with excellent schools to work at and communities attached that were inexpensive, low crime, and with excellent school systems. We got lucky when we landed in College Station. There Art Splendidness have been many times in recent years that we have Katie Killer - Wonko The Sane tried to move away but ultimately it did not come to fruition, most of the time because we’d say to our- Folks That Did the Other Shit For Us selves, “OK, where can we find a place in this new timOTHY danger - Mike e. downey - Jorge goyco - todd town that’s like here but not, you know, here?” and Hansen - chris Kirkpatrick - Jessica little - Amanda we could not find a satisfactory answer.