Universi^ Micrdfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ieri a Început Vizita Oficială De Prietenie a Tovarășului Nicolae

PROLETARI DIN TOATE ȚĂRILE, UNIȚI-VĂ! ORGAN AL COMITETULUI CENTRAL AL PARTIDULUI COMUNIST ROMÂN Anul LI Nr. 12 330 Miercuri 14 aprilie 1982 6 PAGINI — 50 BANI în spiritul tradiționalelor relații de caldă prietenie, al dorinței comune de a da noi dimensiuni colaborării multilaterale dintre cele două țări, partide și popoare Ieri a început vizita oficială de prietenie a tovarășului Nicolae Ceaușescu, împreună cu tovarășa Elena Ceaușescu, în Republica Populară Chineză Banchet în onoarea tovarășului Nicolae înalții soli ai poporului român primiți Ceaușescu si a tovarășei Elena Ceausescu cu manifestări de profundă stimă la Beijing în onoarea tovarășului Nicolae Yaobang, președintele Comitetului al Consiliului de Stat, Chen Muhua, în continuare, în sala de recepție, Ceaușescu, secretar general al Parti Central al Partidului Comunist Chi membru supleant al Biroului Politic tovarășului Nicolae Ceaușescu și to 13 aprilie 1982. în această zi a rodnice dintre țările și partidele al Partidului Comunist Român, pre dului Comunist Român, președintele nez, Zhao Ziyang, premierul Consi al C.C. al P.C.C., vicepremier al Con varășei Elena Ceaușescu le sint pre începui vizita oficială de prietenie noastre. ședintele Republicii Socialiste Româ Republicii Socialiste România, și a liului de Stat al R. P. Chineze, de siliului de Stat, ministrul comerțului zentate persoanele oficiale chineze Întreprinsă in Republica Populară Sub semnul acestor frumoase tra nia, și a tovarășei Elena Ceaușescu, tovarășei-Elena Ceaușescu, Comitetul alți tovarăși din conducerea de partid exterior și relațiilor economice, Ji care iau parte la banchet. Chineză de tovarășul Nicolae diții s-a desfășurat ceremonia pri la care au adresat calde urări de Central al Partidului Comunist Chi și de stat — Li Xiannian, vicepre Pengfei, membru al C.C. -

Hong Kong, 1997 : the Politics of Transition

The Politics of Transition Enbao Wang .i.' ^ m iip Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre ^ff from Hung On-To Memorial Library ^<^' Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from IVIulticultural Canada; University of Toronto Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/hongkong1997poli00wang Hong Kong, 1997 Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre Spadina 1 Crescent, Rjn. Ill • Tbronto, Canada • M5S lAl Hong Kong, 1997 The Politics of Transition Enbao Wang LYNNE RIENNER PUBLISHERS BOULDER LONDON — Published in the United States of America in 1995 by L\ nne Rienner Publishers. Inc. 1800 30lh Street. Boulder. Colorado 80301 and in the United Kingdom by U\ nne Rienner Publishers. Inc. 3 Henrietta Street. Covenl Garden. Uondon WC2E 8LU © 1995 by Lynne Rienner Publishers, inc. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wang. Enbao. 1953- Hong Kong. 1997 : the politics of transition / Enbao Wang. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55587-597-1 (he: alk. paper) 1 . Hong Kong—Politics and government. 2. Hong Kong—Relations China. 3. China—Relations — Hong Kong. 4. China— Politics and government— 1976- 1. Title. bs796.H757W36 1995 951.2505—dc20 95-12694 CIP British Cataloguing in Publication Data A Cataloguing in Publication record for this book is available from the British Uibrarv. This book was t\peset b\ Uetra Libre. Boulder. Colorado. Printed and bound in the United States of .America The paper used in this publication meets the requirements @ of the .American National Standard for Permanence -

Final Program of CCC2020

第三十九届中国控制会议 The 39th Chinese Control Conference 程序册 Final Program 主办单位 中国自动化学会控制理论专业委员会 中国自动化学会 中国系统工程学会 承办单位 东北大学 CCC2020 Sponsoring Organizations Technical Committee on Control Theory, Chinese Association of Automation Chinese Association of Automation Systems Engineering Society of China Northeastern University, China 2020 年 7 月 27-29 日,中国·沈阳 July 27-29, 2020, Shenyang, China Proceedings of CCC2020 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2040A -USB ISBN: 978-988-15639-9-6 CCC2020 Copyright and Reprint Permission: This material is permitted for personal use. For any other copying, reprint, republication or redistribution permission, please contact TCCT Secretariat, No. 55 Zhongguancun East Road, Beijing 100190, P. R. China. All rights reserved. Copyright@2020 by TCCT. 目录 (Contents) 目录 (Contents) ................................................................................................................................................... i 欢迎辞 (Welcome Address) ................................................................................................................................1 组织机构 (Conference Committees) ...................................................................................................................4 重要信息 (Important Information) ....................................................................................................................11 口头报告与张贴报告要求 (Instruction for Oral and Poster Presentations) .....................................................12 大会报告 (Plenary Lectures).............................................................................................................................14 -

Shen Yueyue, Vice-Chairwoman of the National People's Congress

Zhang Baowen, vice-chairman of the National People’s Congress standing committee, meets with Vaira Vike-Freiberga, president of the World Leardership Alliance, before the opening ceremony Shen Yueyue, vice-chairwoman of the National People’s Congress standing committee, poses with delegates to the reception for celebrating the 25th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the Baltic states Contents Express News FOCUS 04 President Li Xiaolin Meets with Lord Powell, Member of the House of Lords of the UK Parliament / Wang Fan 04 Vice President Xie Yuan Meets with Delegation of Colombian Governors / Lin Zhichang 05 The Opening Ceremony of a Large-Scale Relics Touring Exhibition of Chinese Characters / Yu Xiaodong 05 Vice-President Lin Yi Meets with Premier of the British Virgin Islands / Wang Fan 10 06 Vice President Song Jingwu Meets with Mr. Kawamura Takeo / Fu Bo 06 Secretary-General Li Xikui Leads a Delegation to Jiangxi / Sun Yutian 07 China-Latin America and Caribbean 2016 Year of Culture Exchange / Wang Lijuan 07 The Chinese Culture Tour for Cultural Officials of Relevant Embassies in China 14 and Foreign Experts in Changsha / Gao Hui 08 Enjoy the Global “Music Journey” on the Doorstep / Chengdu Friendship Association 08 “Panda Chengdu”Shines in Ljubljana / Chengdu Friendship Association Global Vision 3020 09 G20 Hangzhou Summit Points the Way for the World Economy / He Yafei 2016 Imperial Springs International Forum 12 2016 Imperial Springs International Forum / Department of American & Oceanian Affairs -

Frontier Politics and Sino-Soviet Relations: a Study of Northwestern Xinjiang, 1949-1963

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Frontier Politics And Sino-Soviet Relations: A Study Of Northwestern Xinjiang, 1949-1963 Sheng Mao University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Mao, Sheng, "Frontier Politics And Sino-Soviet Relations: A Study Of Northwestern Xinjiang, 1949-1963" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2459. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2459 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2459 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frontier Politics And Sino-Soviet Relations: A Study Of Northwestern Xinjiang, 1949-1963 Abstract This is an ethnopolitical and diplomatic study of the Three Districts, or the former East Turkestan Republic, in China’s northwest frontier in the 1950s and 1960s. It describes how this Muslim borderland between Central Asia and China became today’s Yili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture under the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The Three Districts had been in the Soviet sphere of influence since the 1930s and remained so even after the Chinese Communist takeover in October 1949. After the Sino- Soviet split in the late 1950s, Beijing transformed a fragile suzerainty into full sovereignty over this region: the transitional population in Xinjiang was demarcated, border defenses were established, and Soviet consulates were forced to withdraw. As a result, the Three Districts changed from a Soviet frontier to a Chinese one, and Xinjiang’s outward focus moved from Soviet Central Asia to China proper. The largely peaceful integration of Xinjiang into PRC China stands in stark contrast to what occurred in Outer Mongolia and Tibet. -

The CCP Central Committee's Leading Small Groups Alice Miller

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 26 The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups Alice Miller For several decades, the Chinese leadership has used informal bodies called “leading small groups” to advise the Party Politburo on policy and to coordinate implementation of policy decisions made by the Politburo and supervised by the Secretariat. Because these groups deal with sensitive leadership processes, PRC media refer to them very rarely, and almost never publicize lists of their members on a current basis. Even the limited accessible view of these groups and their evolution, however, offers insight into the structure of power and working relationships of the top Party leadership under Hu Jintao. A listing of the Central Committee “leading groups” (lingdao xiaozu 领导小组), or just “small groups” (xiaozu 小组), that are directly subordinate to the Party Secretariat and report to the Politburo and its Standing Committee and their members is appended to this article. First created in 1958, these groups are never incorporated into publicly available charts or explanations of Party institutions on a current basis. PRC media occasionally refer to them in the course of reporting on leadership policy processes, and they sometimes mention a leader’s membership in one of them. The only instance in the entire post-Mao era in which PRC media listed the current members of any of these groups was on 2003, when the PRC-controlled Hong Kong newspaper Wen Wei Po publicized a membership list of the Central Committee Taiwan Work Leading Small Group. (Wen Wei Po, 26 December 2003) This has meant that even basic insight into these groups’ current roles and their membership requires painstaking compilation of the occasional references to them in PRC media. -

Comrades-In-Arms: the Chinese Communist Party's Relations With

Cold War History ISSN: 1468-2745 (Print) 1743-7962 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcwh20 Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76 Joshua Eisenman To cite this article: Joshua Eisenman (2018): Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76, Cold War History To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2018.1440549 Published online: 20 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fcwh20 COLD WAR HISTORY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2018.1440549 Comrades-in-arms: the Chinese Communist Party’s relations with African political organisations in the Mao era, 1949–76 Joshua Eisenman LBJ School of Public Affairs, the University of Texas at Austin, Austin, United States ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This study examines the evolution of the Chinese Communist China; Africa; Communism; Party’s (CCP) motives, objectives, and methods vis-à-vis its African Mao; Soviet Union counterparts during the Mao era, 1949–76. Beginning in the mid- 1950s, to oppose colonialism and US imperialism, the CCP created front groups to administer its political outreach in Africa. In the 1960s and 1970s, this strategy evolved to combat Soviet hegemony. Although these policy shifts are distinguished by changes in CCP methods and objectives towards Africa, they were motivated primarily by life-or- death intraparty struggles among rival political factions in Beijing and the party’s pursuit of external sources of regime legitimacy. -

The Role of the Chinese Military in National Security Policymaking Revised Edition

The Role of the Chinese Military in National Security Policymaking Revised Edition Michael D. Swaine Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense R National Defense Research Institute Approved for public release, distribution unlimited The research described in this report was supported by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), under RAND’s National Defense Research Institute, a federally funded research and development center supported by the OSD, the Joint Staff, and the defense agencies, Contract DASW01-95-C-0059. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Swaine, Michael D. The role of the Chinese military in national security policymaking / Michael D. Swaine. p. cm. “Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense by RAND’s National Defense Research Institute.” “MR-782-1-OSD.” Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-8330-2527-9 1. China—Military policy. 2. National security—China. I. National Defense Research Institute (U.S.). II. Title. UA835.S83 1998 355' .033051—dc21 97-22694 CIP RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 1998 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 1998 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1333 H St., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005-4707 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Internet: [email protected] PREFACE This report documents one component of a year-long effort to ana- lyze key factors influencing China’s national security strategies, policies, and military capabilities, and their potential consequences for longer-term U.S. -

Searchable PDF Format

voL xxrx NO. IO OCTOBER ReconstFrrcts r980 Australia: A .$ 071 Neu NZ S 084 UK: i9 p LJSA: li 078 PUBLISHED MONTHLY Iry Ery.GlSt{, FRENCH, SPANISH, ARABIC, GERMAN, PORTUGUESE AND cHlNEsE BY THE cHtNA WELFARE rNsnrurE (sooNc c'xtr.ro uno, cuninu[nj vot. xxtx No. 10 ocToBER 1980 Articles of the Month CONTENTS Out ol the Ruint Tongshon Report After World's Worst Quake-Tangshan Rises Anew 2 Tongshon, one of Chi- A Power Plant no's most importont in- Restored, A Family Beborn I dustriol cities, wos Builders of the New City 11 leveled in the greot 1976 eorthquoke. A 1,700 Paraplegics 13 f ive-port report on its Sun Xiuqing's New Life IJ revivol, by o teom of reporters who spent two Notionolities weeks there. Present Policies for Tibet (lnterview) tb Poge 2 Economics Xue Muqiao lnnovative Economist 21 Present Policies lor Tibet 'Rare - Earths' Abound 56 A responsible codre Miedicine of the Stote Notion- olities Affoirs Commil. New Hands for Accident Victims 54 sion exploins the re. Culture cent dhonges in po- ond Art licy for Tibet, where New Plays About Taiwan 28 post mistokes hod Performers lrom Abroad produced economit 42 choos ond resentmenl The'Guqin'-Age-old Musical lnstrument 52 omong the people. Poge Peasant Paintings from Shanghai,s Outskirts 64 t6 Annols of Friendship lnnovotive Economist Xue Muqioo Frank Coe Ma Haide.(Dr George Hatem) 30 Across His new best.sellinq book the Lond onolyzes unsolved-orob- Dragon Boat Festival 24 lems of Grino's s6ciol- ist economy Cities of China: Chengdu 34 ond offers guidelines for the future. -

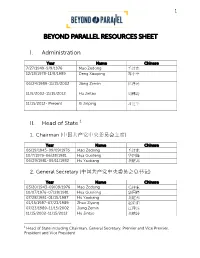

Beyond Parallel Resources Sheet

1 BEYOND PARALLEL RESOURCES SHEET I. Administration Year Name Chinese 7/27/1949-9/9/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 12/18/1978-11/8/1989 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 06/24/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/5/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 11/15/2012- Present Xi Jinping 习近平 II. Head of State 1 1. Chairman (中国共产党中央委员会主席) Year Name Chinese 06/19/1945-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/7/1976-06/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 06/29/1981-09/11/1982 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 2. General Secretary (中国共产党中央委员会总书记) Year Name Chinese 03/20/1943-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/07/1976-07/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 07/28/1981-01/15/1987 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 01/15/1987-07/23/1989 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 07/23/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/15/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 1 Head of State including Chairman, General Secretary, Premier and Vice Premier, President and Vice President 2 11/15/2012-Present Xi Jinping 习近平 3. Premier (中华人民共和国国务院总理) Year Name Chinese 10/1949-01/1976 Zhou Enlai 周恩来 2/2/1976-09/10/1980 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 09/10/1980-11/24/1987 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 11/24/1987-03/17/1998 Li Peng 李鹏 03/17/1998-03/16/2003 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/16/2003-03/15/2013 Wen Jiabao 温家宝 03/15/2013-Present Li Keqiang 李克强 4. Vice Premier (中华人民共和国国务院副总理) Year Name Chinese 09/15/1954-12/21/1964 Chen Yun 陈云 12/21/1964-09/13/1971 Lin Biao 林彪 09/13/1971-09/10/1980 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 09/10/1980-03/25/1988 Wan Li 万里 03/25/1988-3/05/1993 Yao Yilin 姚依林 3/25/1993-03/17/1998 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/17/1998-03/06/2003 Li Lanqing 李岚清 03/06/2003-06/02/2007 Huang Ju 黄菊 06/02/2007-03/16/2008 Wu Yi 吴仪 03/16/2008-03/16/2013 Li Keqiang 李克强 03/16/2013-Present Zhang Gaoli 张高丽 5. -

The Harmonization of Hong Kong and PRC Law Tahrih V

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 30 Article 3 Issue 4 Summer 1999 1999 Mixing River Water and Well Water: The Harmonization of Hong Kong and PRC Law Tahrih V. Lee Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tahrih V. Lee, Mixing River Water and Well Water: The Harmonization of Hong Kong and PRC Law, 30 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 627 (1999). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol30/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mixing River Water and Well Water: The Harmonization of Hong Kong and PRC Law The 1998 Wing Tat Lee Lecture* Tahirih V. Lee** The Chinese language is rich with pithy yet evocative sayings. Their terseness makes them easy to remember, fun to use, and relatively safe when the intended meaning contradicts official discourse. One such saying, which enjoys a great deal of popularity in Hong Kong, is he soi bat fan hah soi. Roughly translated, this means, "River water does not mix with well water." The saying's underlying meaning cannot be found in dictionaries or official sources. According to rumor, however, river water represents Guangdong' natives and well water refers to Hong Kong natives. A likely reason for the saying's popularity in Hong Kong is its emphasis on the gulf between Hong Kong locals and the inhabitants of mainland China. -

The People's Liberation Army General Political Department

The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao October 14, 2013 Cover image and below: Chinese nuclear test. Source: CCTV. | Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Political Warfare | About the Project 2049 Institute Cover image source: 997788.com. Above-image source: ekooo0.com The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide Above-image caption: “We must liberate Taiwan” decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. The organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region- specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. www.project2049.net 1 | Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Political Warfare | TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….……………….……………………….3 Universal Political Warfare Theory…………………………………………………….………………..………………4 GPD Liaison Department History…………………………………………………………………….………………….6 Taiwan Liberation Movement…………………………………………………….….…….….……………….8 Ye Jianying and the Third United Front Campaign…………………………….………….…..…….10 Ye Xuanning and Establishment of GPD/LD Platforms…………………….……….…….……….11 GPD/LD and Special Channel for Cross-Strait Dialogue………………….……….……………….12 Jiang Zemin and Diminishment of GPD/LD Influence……………………….…….………..…….13