To Get Rich Is Unprofessional: Chinese Military Corruption in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China's

C O R P O R A T I O N Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China’s Aerospace Forces Selections from the Inaugural Conference of the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) Edmund J. Burke, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Mark R. Cozad, Timothy R. Heath For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF340 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9549-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface On June 22, 2015, the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), in conjunction with Headquarters, Air Force, held a day-long conference in Arlington, Virginia, titled “Assessing Chinese Aerospace Training and Operational Competence.” The purpose of the conference was to share the results of nine months of research and analysis by RAND researchers and to expose their work to critical review by experts and operators knowledgeable about U.S. -

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

China's Aircraft Carrier Ambitions

CHINA’S AIRCRAFT CARRIER AMBITIONS An Update Nan Li and Christopher Weuve his article will address two major analytical questions. First, what are the T necessary and suffi cient conditions for China to acquire aircraft carriers? Second, what are the major implications if China does acquire aircraft carriers? Existing analyses on China’s aircraft carrier ambitions are quite insightful but also somewhat inadequate and must therefore be updated. Some, for instance, argue that with the advent of the Taiwan issue as China’s top threat priority by late 1996 and the retirement of Liu Huaqing as vice chair of China’s Central Military Commission (CMC) in 1997, aircraft carriers are no longer considered vital.1 In that view, China does not require aircraft carriers to capture sea and air superiority in a war over Taiwan, and China’s most powerful carrier proponent (Liu) can no longer infl uence relevant decision making. Other scholars suggest that China may well acquire small-deck aviation platforms, such as helicopter carriers, to fulfi ll secondary security missions. These missions include naval di- plomacy, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and antisubmarine warfare.2 The present authors conclude, however, that China’s aircraft carrier ambitions may be larger than the current literature has predicted. Moreover, the major implications of China’s acquiring aircraft carriers may need to be explored more carefully in order to inform appropriate reactions on the part of the United States and other Asia-Pacifi c naval powers. This article updates major changes in the four major conditions that are necessary and would be largely suffi cient for China to acquire aircraft carriers: leadership endorsement, fi nancial affordability, a relatively concise naval strat- egy that defi nes the missions of carrier operations, and availability of requisite 14 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW technologies. -

The Coming Show Trial of General Xu Caihou

Lawyers, Guns and Money: The Coming Show Trial of General Xu Caihou James Mulvenon On 30 June 2014, the Chinese Communist Party expelled former Politburo member and Central Military Commission vice-chair Xu Caihou for corruption following a three-month investigation. His case was transferred from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection to the military justice system for possible criminal prosecution, making him the highest- ranking military officer to be prosecuted since the founding of the PRC in 1949. His primary crime involved “trading offices for bribes,” and reportedly was uncovered during the investigation of General Gu Junshan. This article examines the Xu case, and assesses its implications for Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign and the military. Introduction On 30 June 2014, the Chinese Communist Party expelled former Politburo member and Central Military Commission vice-chair Xu Caihou for corruption following a three- month investigation. Xu, 70, joined the CMC in 1999 as director of the General Political Department and served as vice-chairman from 2004 to 2013. His case was transferred from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection to the military justice system for possible criminal prosecution, making him the highest-ranking military officer to be prosecuted since the founding of the PRC in 1949. His primary crime involved “trading offices for bribes,” which was reportedly uncovered during the investigation of disgraced former General Logistics Department deputy Gu Junshan (see CLM 37).1 This article examines the Xu case, and assesses its implications for Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign and the military. Xu was born in 1943 in Liaoning, and joined the PLA in 1963. -

Other Approaches to Civil-Military Integration: the Chinese and Japanese Arms Industries

Other Approaches to Civil-Military Integration: The Chinese and Japanese Arms Industries March 1995 OTA-BP-ISS-143 GPO stock #052-003-01408-4 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Other Approaches to Civil-Military Integration: The Chinese and Japanese Arms Industries, BP-ISS-143 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 1995). Foreword s part of its assessment of the potential for integrating the civil and military industrial bases, the Office of Technology Assessment con- sidered how the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Japan, two Asian states with sizable defense industries, have succeeded in Aachieving significant levels of civil-military integration (CMI). CMI involves the sharing of fixed costs by promoting the use of common technologies, processes, labor, equipment, material, and/or facilities. CMI can not only lower costs, but in some cases, it can also expedite the introduction of advanced commercial products and processes to the defense sector. The paper is divided into two sections, one on the PRC and one on Japan. Each section describes the structure and management of the respective defense industrial base and then compares it with its U.S. counterpart. The paper then assesses the degree to which lessons from the PRC and Japanese cases can be applied to the U.S. defense technology and industrial base (DTIB). Although the political and security situations of the PRC and Japan, as well as their CMI objectives, differ from those of the United States, several interest- ing observations can be made. The Japanese, for example, with a limited de- fense market and an American security guarantee, emphasize dual-use design as well as the commercial aspects of many defense developments. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

FIREARMS NEWS - Firearmsnews.Com VOLUME 70 - ISSUE 13

FORMERLY GUN SALES, REVIEWS, & INFORMATION VOLUME 70 | ISSUE 13 | 2016 PAGE 2 FIREARMS NEWS - firearmsnews.com VOLUME 70 - ISSUE 13 TM KeyMod™ is the tactical KeyMod is here! industry’s new modular standard! • Trijicon AccuPoint TR24G 1-4x24 Riflescope $1,020.00 • American Defense • BCM® Diamondhead RECON X Scope ® Folding Front Sight $99.00 • BCM Diamondhead Mount $189.95 Folding Rear Sight $119.00 • BCM® KMR-A15 KeyMod Rail • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ Handguard 15 Inch $199.95 Compensator Mod 0 $89.95 • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ ® BCMGUNFIGHTER™ KMSM • BCM Low Profile QD End Plate $16.95 • KeyMod QD Sling Mount $17.95 Gas Block $44.95 • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ Stock $55.95 Vertical Grip Mod 3 $18.95 GEARWARD Ranger • ® Band 20-Pak $10.00 BCM A2X Flash • BCMGUNFIGHTER™ Suppressor $34.95 Grip Mod 0 $29.95 B5 Systems BCMGUNFIGHTER™ SOPMOD KeyMod 1-Inch Bravo Stock $58.00 Ring Light BCM® KMR-A Mount KeyMod Free Float For 1” diameter Rail Handguards lights $39.95 Blue Force Gear Same as the fantastic original KMR Handguards but machined from aircraft aluminum! BCMGUNFIGHTER™ VCAS Sling $45.00 BCM 9 Inch KMR-A9 . $176.95 KeyMod Modular BCM 10 Inch KMR-A10 . $179.95 BCM 13 Inch KMR-A13 . $189.95 Scout Light Mount BCM 15 Inch KMR-A15 . $199.95 For SureFire Scout BCM® PNT™ Light $39.95 Trigger Assembly Polished – Nickel – Teflon BCMGUNFIGHTER™ $59.95 KeyMod Modular PWS DI KeyMod Rail Handguard Light Mount Free float KeyMod rail for AR15/M4 pattern rifles. For 1913 mounted Wilson PWS DI 12 Inch Rail . $249.95 lights $39.95 Combat PWS DI 15 Inch Rail . -

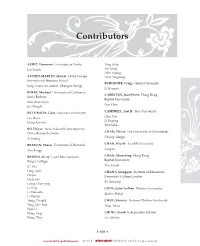

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Ieri a Început Vizita Oficială De Prietenie a Tovarășului Nicolae

PROLETARI DIN TOATE ȚĂRILE, UNIȚI-VĂ! ORGAN AL COMITETULUI CENTRAL AL PARTIDULUI COMUNIST ROMÂN Anul LI Nr. 12 330 Miercuri 14 aprilie 1982 6 PAGINI — 50 BANI în spiritul tradiționalelor relații de caldă prietenie, al dorinței comune de a da noi dimensiuni colaborării multilaterale dintre cele două țări, partide și popoare Ieri a început vizita oficială de prietenie a tovarășului Nicolae Ceaușescu, împreună cu tovarășa Elena Ceaușescu, în Republica Populară Chineză Banchet în onoarea tovarășului Nicolae înalții soli ai poporului român primiți Ceaușescu si a tovarășei Elena Ceausescu cu manifestări de profundă stimă la Beijing în onoarea tovarășului Nicolae Yaobang, președintele Comitetului al Consiliului de Stat, Chen Muhua, în continuare, în sala de recepție, Ceaușescu, secretar general al Parti Central al Partidului Comunist Chi membru supleant al Biroului Politic tovarășului Nicolae Ceaușescu și to 13 aprilie 1982. în această zi a rodnice dintre țările și partidele al Partidului Comunist Român, pre dului Comunist Român, președintele nez, Zhao Ziyang, premierul Consi al C.C. al P.C.C., vicepremier al Con varășei Elena Ceaușescu le sint pre începui vizita oficială de prietenie noastre. ședintele Republicii Socialiste Româ Republicii Socialiste România, și a liului de Stat al R. P. Chineze, de siliului de Stat, ministrul comerțului zentate persoanele oficiale chineze Întreprinsă in Republica Populară Sub semnul acestor frumoase tra nia, și a tovarășei Elena Ceaușescu, tovarășei-Elena Ceaușescu, Comitetul alți tovarăși din conducerea de partid exterior și relațiilor economice, Ji care iau parte la banchet. Chineză de tovarășul Nicolae diții s-a desfășurat ceremonia pri la care au adresat calde urări de Central al Partidului Comunist Chi și de stat — Li Xiannian, vicepre Pengfei, membru al C.C. -

10. HONG KONG's STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE UNDER CHINESE SOVEREIGNTY Tai Ming Cheung Hong Kong Has Come a Long Way Since It Was

- 170 - 10. HONG KONG’S STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE UNDER CHINESE SOVEREIGNTY Tai Ming Cheung Hong Kong has come a long way since it was dismissed as a barren rock a century and a half ago. This bastion of freewheeling capitalism today is a leading international financial, trading and communications center serving one of the world’s fastest growing economic regions. But Hong Kong is also entering a period of considerable change and uncertainty following its reversion to Chinese sovereignty that is likely to have a far- reaching impact on its strategic importance and role over the coming years. As a British colony, Hong Kong was an important outpost for the West to keep an eye on China and safeguard busy sea-lanes. Under Chinese rule, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) will play a crucial role in boosting China’s economic growth and promoting Beijing’s long-term goal of reunification with Taiwan. How China handles Hong Kong’s return will have major consequences for the territory as well as for China’s relations with the international community. The world will be watching very carefully whether Beijing will adhere to its international commitments of allowing the SAR to retain a high degree of autonomy. The U.S. has said that the transition will be a key issue in determining its future relations with China. This paper will examine the strategic implications of Hong Kong's return to Chinese rule. Several key issues will be explored: • Hong Kong's past and present strategic significance. • The stationing of the People's Liberation Army (PLA) in Hong Kong. -

Hong Kong, 1997 : the Politics of Transition

The Politics of Transition Enbao Wang .i.' ^ m iip Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre ^ff from Hung On-To Memorial Library ^<^' Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from IVIulticultural Canada; University of Toronto Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/hongkong1997poli00wang Hong Kong, 1997 Canada-Hong Kong Resource Centre Spadina 1 Crescent, Rjn. Ill • Tbronto, Canada • M5S lAl Hong Kong, 1997 The Politics of Transition Enbao Wang LYNNE RIENNER PUBLISHERS BOULDER LONDON — Published in the United States of America in 1995 by L\ nne Rienner Publishers. Inc. 1800 30lh Street. Boulder. Colorado 80301 and in the United Kingdom by U\ nne Rienner Publishers. Inc. 3 Henrietta Street. Covenl Garden. Uondon WC2E 8LU © 1995 by Lynne Rienner Publishers, inc. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wang. Enbao. 1953- Hong Kong. 1997 : the politics of transition / Enbao Wang. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55587-597-1 (he: alk. paper) 1 . Hong Kong—Politics and government. 2. Hong Kong—Relations China. 3. China—Relations — Hong Kong. 4. China— Politics and government— 1976- 1. Title. bs796.H757W36 1995 951.2505—dc20 95-12694 CIP British Cataloguing in Publication Data A Cataloguing in Publication record for this book is available from the British Uibrarv. This book was t\peset b\ Uetra Libre. Boulder. Colorado. Printed and bound in the United States of .America The paper used in this publication meets the requirements @ of the .American National Standard for Permanence -

June 10, 2021 Hearing Transcript

HEARING ON CHINA’S NUCLEAR FORCES HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 2021 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2021 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, CHAIRMAN ROBIN CLEVELAND, VICE CHAIRMAN Commissioners: BOB BOROCHOFF DEREK SCISSORS JEFFREY FIEDLER HON. JAMES M. TALENT KIMBERLY GLAS ALEX N. WONG HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN MICHAEL R. WESSEL ROY D. KAMPHAUSEN The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 106–398 (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002), as amended by: The Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act, 2002, Pub. L. No. 107–67 (Nov. 12, 2001) (regarding employment status of staff and changing annual report due date from March to June); The Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003, Pub. L. No. 108–7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); The Science, State, Justice, Commerce, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2006, Pub. L. No. 109–108 (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of the Commission and applicability of FACA); The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008, Pub. L. No. 110–161 (Dec. 26, 2007) (regarding submission of accounting reports; printing and binding; compensation for the executive director; changing annual report due date from June to December; and travel by members of the Commission and its staff); The Carl Levin and Howard P.