Who Feels Scottish? National Identities and Ethnicity in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Variation in Outcome of People Hospitalised During the First COVID

Open access Original research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048335 on 18 August 2021. Downloaded from Ethnic variation in outcome of people hospitalised during the first COVID-19 epidemic wave in Wales (UK): an analysis of national surveillance data using Onomap, a name- based ethnicity classification tool Daniel Rh Thomas ,1,2 Oghogho Orife ,1 Amy Plimmer,1 Christopher Williams,1 George Karani,2 Meirion R Evans,1 Paul Longley,3 Janusz Janiec,4 Roiyah Saltus,5 Ananda Giri Shankar6 To cite: Thomas DR, Orife O, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Plimmer A, et al. Ethnic Objective To identify ethnic differences in proportion variation in outcome of people positive for SARS- CoV-2, and proportion hospitalised, hospitalised during the first ► Secondary analysis of data obtained through routine proportion admitted to intensive care and proportion died COVID-19 epidemic wave national COVID-19 surveillance. in hospital with COVID-19 during the first epidemic wave in Wales (UK): an analysis ► Studies relying on clinician reported ethnicity con- of national surveillance in Wales. tain high proportions of missing and poor quality data using Onomap, a Design Descriptive analysis of 76 503 SARS- CoV-2 tests data. name- based ethnicity carried out in Wales to 31 May 2020. Cohort study of 4046 ► Using a proven name-based classifier, we were able classification tool. BMJ Open individuals hospitalised with confirmed COVID-19 between to assign ethnicity to nearly all participants. 2021;11:e048335. doi:10.1136/ 1 March and 31 May. In both analyses, ethnicity was While sensitivity and specificity of the classifier bmjopen-2020-048335 ► assigned using a name- based classifier. -

Two Case Studies in Self-Determination: the Rock and the Bailiwick

Two Case Studies in Self-Determination: The Rock and the Bailiwick INGE V. PORTER* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 340 II. SELF-DETERMINATION ....................................................................................... 342 A. History...................................................................................................... 342 B. General Scope and Content...................................................................... 345 1. Decolonization................................................................................... 345 2. Post-Decolonization.......................................................................... 349 3. Historic Title ...................................................................................... 350 4. Limits to the Principleof Self-Determination.................................... 354 C. M icrostates ............................................................................................... 356 D. Future Trends ........................................................................................... 357 1. The Demise of the Principle of Self-Determination?......................... 357 2. Self-Determination as Customary Law .............................................. 358 3. Self-Determination as a Right to a Democratic Form of Government ......................................................................... 360 III. THE CASE OF GIBRALTAR ................................ -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Scotland's Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report

Scotland’s Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report Scotland’s Census 2021 – Ethnic Group Topic Report Table of Contents 1. Main Points .......................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 3. Background ......................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Ethnic group in the census .............................................................................. 5 3.2 The 2011 Ethnic Group and National Identity Questions ................................. 6 3.3 Questions in other UK 2011 Censuses............................................................ 8 3.4 Alternative sources .......................................................................................... 9 4. Understanding user need for 2021 ...................................................................... 9 5. 2017 Question Testing ....................................................................................... 10 5.1 Cognitive testing ............................................................................................ 11 5.2 Quantitative testing ........................................................................................ 15 6. Next Steps ......................................................................................................... 16 Annex A: 2017 Cognitive Test ................................................................................. -

ANALYSIS of 2011 CENSUS DATA Irish Community Statistics, England and Selected Urban Areas

ANALYSIS OF 2011 CENSUS DATA Irish Community Statistics, England and Selected Urban Areas REPORT FOR NORTH WEST Louise Ryan, Alessio D’Angelo, Michael Puniskis, Neil Kaye July 2014 Supported and funded by: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Irish in Britain is funded by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Emigrant Support Programme (ESP). The ESP supports Irish communities overseas by funding non-profit organisations and projects; allowing the development of more strategic links with the global Irish and support of frontline welfare services that help the most vulnerable members of Irish communities overseas. The Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) at Middlesex University, set up 1990, is a dynamic research centre with a proven track record of delivering projects on time and on budget. The centre draws together a range of staff with expertise in social policy, migration, health, care, welfare and service provision, education, the needs of families, women, children, religion, culture and identity. To view reports from our recent research projects visit our web page: www.sprc.info Irish in Britain is the national representative organisation for the Irish voluntary and community sector across Britain. It provides crucial support and advice to its diverse membership on policy, funding, governance and sustainability. It undertakes research into the needs of the most vulnerable in the community and represents those to Government in Britain and Ireland. Irish in Britain is actively involved in promoting Irish culture, creating Irish -

Who Identifies As Welsh? National

November 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who identifies asWelsh? National identities and ethnicity in Wales Summary • In Wales, 1.8 million people identify only as Welsh (58% of • People born in Wales are more likely to report only a Welsh the population) and 218,000 identify as Welsh and British national identity (76%). People born in Oceania and North (7% of the population). America and the Caribbean are more likely to report only a Welsh national identity (14% and 10% respectively) than • Mixed ethnic groups are more likely to identify with only people born in England (8%). a Welsh national identity than all other ethnic minority groups, with the highest proportion being amongst the White and Black Caribbean (59%) group. Introduction Since devolution, the Welsh Government has sought to • Mixed groups are more likely to identify only as Welsh support a common Welsh national identity through the ‘One (47%) than mixed groups in England (46%) and Scotland Wales’ strategy. This has included, for example, strengthening (37%) identify as English or Scottish only. the place of ‘Wales in the World’ and continued support for 1 • The ethnic groups in Wales most likely to identify only as the Welsh language. The inclusion of a question on national British are Bangladeshi (64%), Pakistani (56%) and Black identity in the 2011 Census provides us with an opportunity Caribbean (41%). to examine how people living in Wales describe themselves. The Census shows that 58% of people living in Wales identify • Welsh only national identity is reported more for younger only as Welsh and a further 7% identify as Welsh and British.2 people aged 0 to 17 than those aged 18 or older. -

THE IRISH in BRISTOL, 1938-1985 by Nick Conway BA (Swansea) MA (Liverpool)

1 THE IRISH IN BRISTOL, 1938-1985 by Nick Conway BA (Swansea) MA (Liverpool) Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Arts and Cultural Industries, Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education, University of the West of England August 2018 2 Contents List of Tables and Figures – 4 List of Abbreviations - 5 Abstract – 6 Acknowledgements - 7 Introduction - 8 Research Aims - 9 Research Methodology -9 Definition of terms and census data -13 Importance of the research - 14 Historiography - 18 Chapter 1: Irish Emigration and Bristol - 22 1.1: Leaving Ireland - 23 1.2: The Irish in Bristol - 32 1.3: Patterns of settlement in Bristol - 37 1.4: Experiences of Bristol - 45 1.5: Conclusion - 53 Chapter 2: „Factory and building site fodder‟? - 56 2.1: World War Two workers - 58 2.2: Wartime Irish labour in Bristol - 59 2.3: Transport and housing problems - 61 2.4 Building labourers - 67 2.5 Post-War rebuilding - 68 2.6: NSHC Hostels for Irish building labourers - 72 2.7: Irish nurses in Bristol -79 2.8: Nursing shortages - 83 2.9: The Glenside Irish - 86 2.10: Religious affiliation and geography - 87 2.11: Working at Glenside and further migration - 91 2.12: A positive stereotype? - 92 2.13: Conclusion - 95 Chapter 3: Twentieth century Anglo-Irish relations in the Bristol context - 98 3.1: Irish neutrality - 99 3 3.2: The Treaty Ports - 101 3.3: Loyalists and Nationalists - 104 3.4: Fifth column fears - 107 3.5: The American Note - 110 3.6: Volunteers and emigrants - 111 3.7: Condolences and speeches - 113 3.8: The Republic -

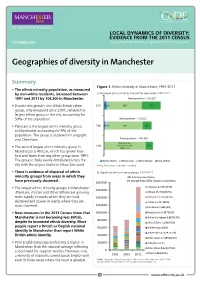

Geographies of Diversity in Manchester

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Manchester Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Manchester, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased between a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 1991 and 2011 by 104,300 in Manchester. Total population – 503,127 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 5% 2% 59% 33% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city, accounting for 59% of the population. Total population – 422,922 • Pakistani is the largest ethnic minority group 2001 2% 4% 74% 19% in Manchester accounting for 9% of the population. The group is clustered in Longsight and Cheetham. Total population – 432,685 85% (includes 1991 White Other and 15% • The second largest ethnic minority group in White Irish Manchester is African, which has grown four- fold and faster than any other group since 1991. The group is fairly evenly distributed across the White Other White Irish White British Non-White city with the largest cluster in Moss Side ward. Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 minority groups from areas in which they 2011 Census estimates (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. 180,000 • The largest ethnic minority groups in Manchester Pakistani 42,904 (73%) 160,000 (Pakistani, African and Other White) are growing African 25,718 (254%) more rapidly in wards where they are least 140,000 Chinese 13,539 (142%) clustered and slower in wards where they are Indian 11,417 (80%) 120,000 most clustered. -

Equality Monitoring Report

Sheffield Hallam University - Equality Monitoring Report Introduction To meet the Public Sector Equality Duty, the government requires all Universities to make equality information available publicly. Adhering to the new Act, this report reflects the make-up of students and staff at Sheffield Hallam University. Four core equality indicators have been assessed: gender; age; ethnicity; disability. Where meaningful, information is disaggregated to show various study levels and intensity (mode). Given the various tiers of data included in the report, please refer to the annex for full descriptions of acronyms and groupings. Contents Page Part 1: Student Equality Indicators Section 1: Overall University Equality Indicators 2 1.1 University Size & Shape Overview 2 1.2 University Gender Profile 2 1.3 University Age Profile 3 1.4 University Ethnicity Profile 4 1.5 University Disability Profile 5 Section 2: Performance Measurements Using Equality Indicators 7 2.1 First Degree Attainment 7 2.2 Employment 9 2.3 Graduate Level Employment 12 Part 2: Staff Equality Indicators Section 3: Staff Equality Indicators 14 3.1 Staff Overview 14 3.2 Staff Gender Profile 14 3.3 Staff Age Profile 14 3.4 Staff Ethnicity Profile 15 3.5 Staff Disability Profile 16 Section 4: Applications for Staff Vacancies 17 4.1 Applications for Staff Vacancies - Overview 17 4.2 Applications for Staff Vacancies - Gender Profile 17 4.3Applications for Staff Vacancies - Age Profile 18 4.4 Applications for Staff Vacancies - Ethnicity Profile 19 4.5 Applications for Staff Vacancies -

Forecasting Sub-National Trends in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in the UK 2 3 A

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.20248382; this version posted April 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 Forecasting sub-national trends in COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the UK 2 3 A. de Figueiredo1,2 4 5 1 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, 6 UK. 7 2 Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, UK. 8 9 [email protected] 10 11 12 The rollout of COVID-19 vaccines has begun to at-risk populations around the world. It is currently 13 unclear whether rejection of the vaccine will pose challenges for achieving herd/community immunity 14 either through large-scale rejection or localised pockets. Here we predict uptake of the vaccine at 15 unprecedented spatial resolution across the UK using a large-scale survey of over 17,000 individuals. 16 Although the majority of the UK population would likely take the vaccine, there is substantial 17 heterogeneity in uptake intent across the UK. Large urban areas, including London and North West 18 England, females, Black or Black British ethnicities, and Polish-speakers are among the least accepting. 19 This study helps identify areas and socio-demographic groups where vaccination levels may not reach 20 those levels reQuired for herd immunity. Identifying clusters of non-vaccinators is extremely important 21 in the context of achieving herd immunity as vaccination “cold-spots” can amplify epidemic spread and 22 disproportionately increase vaccination levels required for herd protection. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Ward, Paul The end of Britishness? A historical perspective Original Citation Ward, Paul (2009) The end of Britishness? A historical perspective. British Politics Review, 4 (3). p. 3. ISSN 1890-4505 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/7726/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ British Politics Review Journal of the British Politics Society, Norway Volume 4 | No. 3 | Summer 2009 The Britishness debate Identity issues in a contested United Kingdom CONTRIBUTORS Paul Ward • Arthur Aughey • Christopher Bryant • Vron Ware Espen Kallevik • Dana Arnold • Kristin M. Haugevik British Politics Review Editorial Volume 4 | No. 3 | Summer 2009 Identity in an age of uncertainty ISSN 1890-4505 Questioning national identity is a sign of our times. -

Ethnic Data Collection in the EU: Can't Seem to Find The

Ethnic data collection in the EU: can’t seem to find the way Lilla Farkas, race ground coordinator, European Network of legal experts on gender equality and non-discrimination,, [email protected] Reporting flurry 1. EDI Report 2014 - OSF & ENAR 2. European Commission 1. Ethnic Data Report and Handbook update 2016 2. Guidance note on hate crimes November 2018 3. FRA: 1. EU MIDIS 2016, 2. hate crime map, 3. PAD November 2018 4. ECRI: general recommendations hate crime, hate speech, Afrophobia EU context - political • Agenda setting & multilevel governance: allies, foes and competitors • Equality data: a problem for many - coalition with other grounds? • Recognised & non-recognised racialised groups - coalition? • European silence on race - including among the racialised groups! • Wallerstein and Balibar 1991: race and gender within class • The Holocaust prism • Migrant and Roma integration frames EU context - jurisprudential 1. The meaning of racial or ethnic origin under EU law 2017: historically contingent 2. ‘racial’ fragmentation: no dominant racial group 3. race reified in case law • = skin colour? as if racial minorities did not have an identity • Timishev v Russia, • Biao v Denmark - Islamophobic undertone • Feryn - Moroccans, xenophobia, Islamophobia or Afrophobia? • CHEZ and Jyske Finans: only ethnicity in RED? ICERD mis-used? • Attrey in CMLR, • Farkas in EADLR Key issues: categorization I. 1. Data on racial origin is seldom collected based on self- identification. 2. How to categorise descent: geographic origin and cultural/religious/linguistic traditions 3. How to link descent with skin colour 4. 30% of PAD Muslim - Islamophobia in Europe Categories: Maghreb, Sub-Saharan African, Other African? Categorization II.