The Changing Ethnic Profiles of Glasgow and Scotland, and the Implications for Population Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report

Scotland’s Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report Scotland’s Census 2021 – Ethnic Group Topic Report Table of Contents 1. Main Points .......................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 3. Background ......................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Ethnic group in the census .............................................................................. 5 3.2 The 2011 Ethnic Group and National Identity Questions ................................. 6 3.3 Questions in other UK 2011 Censuses............................................................ 8 3.4 Alternative sources .......................................................................................... 9 4. Understanding user need for 2021 ...................................................................... 9 5. 2017 Question Testing ....................................................................................... 10 5.1 Cognitive testing ............................................................................................ 11 5.2 Quantitative testing ........................................................................................ 15 6. Next Steps ......................................................................................................... 16 Annex A: 2017 Cognitive Test ................................................................................. -

Conclusion 60

Being Black, Being British, Being Ghanaian: Second Generation Ghanaians, Class, Identity, Ethnicity and Belonging Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah UCL PhD 1 Declaration I, Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Table of Contents Declaration 2 List of Tables 8 Abstract 9 Impact statement 10 Acknowledgements 12 Chapter 1 - Introduction 13 Ghanaians in the UK 16 Ghanaian Migration and Settlement 19 Class, status and race 21 Overview of the thesis 22 Key questions 22 Key Terminology 22 Summary of the chapters 24 Chapter 2 - Literature Review 27 The Second Generation – Introduction 27 The Second Generation 28 The second generation and multiculturalism 31 Black and British 34 Second Generation – European 38 US Studies – ethnicity, labels and identity 40 Symbolic ethnicity and class 46 Ghanaian second generation 51 Transnationalism 52 Second Generation Return migration 56 Conclusion 60 3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical concepts 62 Background and concepts 62 Class and Bourdieu: field, habitus and capital 64 Habitus and cultural capital 66 A critique of Bourdieu 70 Class Matters – The Great British Class Survey 71 The Middle-Class in Ghana 73 Racism(s) – old and new 77 Black identity 83 Diaspora theory and the African diaspora 84 The creation of Black identity 86 Black British Identity 93 Intersectionality 95 Conclusion 98 Chapter 4 – Methodology 100 Introduction 100 Method 101 Focus of study and framework(s) 103 -

ANALYSIS of 2011 CENSUS DATA Irish Community Statistics, England and Selected Urban Areas

ANALYSIS OF 2011 CENSUS DATA Irish Community Statistics, England and Selected Urban Areas REPORT FOR NORTH WEST Louise Ryan, Alessio D’Angelo, Michael Puniskis, Neil Kaye July 2014 Supported and funded by: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Irish in Britain is funded by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Emigrant Support Programme (ESP). The ESP supports Irish communities overseas by funding non-profit organisations and projects; allowing the development of more strategic links with the global Irish and support of frontline welfare services that help the most vulnerable members of Irish communities overseas. The Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) at Middlesex University, set up 1990, is a dynamic research centre with a proven track record of delivering projects on time and on budget. The centre draws together a range of staff with expertise in social policy, migration, health, care, welfare and service provision, education, the needs of families, women, children, religion, culture and identity. To view reports from our recent research projects visit our web page: www.sprc.info Irish in Britain is the national representative organisation for the Irish voluntary and community sector across Britain. It provides crucial support and advice to its diverse membership on policy, funding, governance and sustainability. It undertakes research into the needs of the most vulnerable in the community and represents those to Government in Britain and Ireland. Irish in Britain is actively involved in promoting Irish culture, creating Irish -

Strategic Needs Assessment

Clackmannanshire and Stirling Strategic Plan Strategic Needs Assessment 2016 - 2019 Health and Social Care Partnership Table of Contents Executive Summary.......................................................................................................................................5 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................7 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................................................7 1.2 What is a Strategic Needs Assessment ....................................................................................... 10 1.3 Identified Gaps............................................................................................................................11 2 Population................................................................................................................................................11 2.1 Current Population......................................................................................................................11 2.1.1 Ethnic Origin................................................................................................................................16 2.1.2 Religion........................................................................................................................................16 2.1.3 Sexual Orientation ......................................................................................................................17 -

Who Identifies As Welsh? National

November 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who identifies asWelsh? National identities and ethnicity in Wales Summary • In Wales, 1.8 million people identify only as Welsh (58% of • People born in Wales are more likely to report only a Welsh the population) and 218,000 identify as Welsh and British national identity (76%). People born in Oceania and North (7% of the population). America and the Caribbean are more likely to report only a Welsh national identity (14% and 10% respectively) than • Mixed ethnic groups are more likely to identify with only people born in England (8%). a Welsh national identity than all other ethnic minority groups, with the highest proportion being amongst the White and Black Caribbean (59%) group. Introduction Since devolution, the Welsh Government has sought to • Mixed groups are more likely to identify only as Welsh support a common Welsh national identity through the ‘One (47%) than mixed groups in England (46%) and Scotland Wales’ strategy. This has included, for example, strengthening (37%) identify as English or Scottish only. the place of ‘Wales in the World’ and continued support for 1 • The ethnic groups in Wales most likely to identify only as the Welsh language. The inclusion of a question on national British are Bangladeshi (64%), Pakistani (56%) and Black identity in the 2011 Census provides us with an opportunity Caribbean (41%). to examine how people living in Wales describe themselves. The Census shows that 58% of people living in Wales identify • Welsh only national identity is reported more for younger only as Welsh and a further 7% identify as Welsh and British.2 people aged 0 to 17 than those aged 18 or older. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Creating a New Leisure District in the Heart of Glasgow Glasgow’S Best Is Getting Even Better 8 NEW RESTAURANTS 9 SCREEN CINEMA 60,000 SQ FT £30 MILLION INVESTMENT

Creating a new leisure district in the heart of Glasgow Glasgow’s best is getting even better 8 NEW RESTAURANTS 9 SCREEN CINEMA 60,000 SQ FT £30 MILLION INVESTMENT soon-st-enoch.com 2 Hello Glasgow Glasgow is a great city. Bursting with culture and packed full of character, it’s Scotland’s economic powerhouse, generating a mighty £19.3bn GVA per annum.* But it’s not all serious numbers - If there’s one thing Glasgow loves, it’s shopping, eating out and having fun. * Glasgow City Council 2017 soon-st-enoch.com 3 OVER 440,000 PEOPLE GLASGOW UNDERGOING WORKING IN THE CITY £1 BILLION INVESTMENT Over 440,000 people work within Glasgow’s Always looking to the future, Glasgow is currently bustling city centre.* undergoing £1bn of investment in infrastructure improvements as part of the City Deal, including innovative new Smart City services.** OVER £3 BILLION RETAIL WORTH OVER £6.6 BILLION With city centre retail worth over £3bn, Glasgow is 2nd in CACI’s UK Retail Ranking.*** ANNUAL SPEND With a catchment of 2.8m people with a comparison goods spend of over £6.6 billion. Annual catering spend of £372m.*** OVER 20 MILLION VISITORS ANNUALLY The city’s vibrant shopping and leisure offerings act 130,000 STUDENT as a huge draw - bringing in over 2 million tourists and 20 million day visitors per annum.** POPULATION 130,000 students who call Glasgow home.* * Glasgow City Council 2017 ** FSP December 2016 *** CACI January 2017 soon-st-enoch.com 4 Look East It’s an exciting time to be part of Glasgow’s emerging East End, with the district enjoying a period of significant investment, change and growth. -

THE IRISH in BRISTOL, 1938-1985 by Nick Conway BA (Swansea) MA (Liverpool)

1 THE IRISH IN BRISTOL, 1938-1985 by Nick Conway BA (Swansea) MA (Liverpool) Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Arts and Cultural Industries, Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education, University of the West of England August 2018 2 Contents List of Tables and Figures – 4 List of Abbreviations - 5 Abstract – 6 Acknowledgements - 7 Introduction - 8 Research Aims - 9 Research Methodology -9 Definition of terms and census data -13 Importance of the research - 14 Historiography - 18 Chapter 1: Irish Emigration and Bristol - 22 1.1: Leaving Ireland - 23 1.2: The Irish in Bristol - 32 1.3: Patterns of settlement in Bristol - 37 1.4: Experiences of Bristol - 45 1.5: Conclusion - 53 Chapter 2: „Factory and building site fodder‟? - 56 2.1: World War Two workers - 58 2.2: Wartime Irish labour in Bristol - 59 2.3: Transport and housing problems - 61 2.4 Building labourers - 67 2.5 Post-War rebuilding - 68 2.6: NSHC Hostels for Irish building labourers - 72 2.7: Irish nurses in Bristol -79 2.8: Nursing shortages - 83 2.9: The Glenside Irish - 86 2.10: Religious affiliation and geography - 87 2.11: Working at Glenside and further migration - 91 2.12: A positive stereotype? - 92 2.13: Conclusion - 95 Chapter 3: Twentieth century Anglo-Irish relations in the Bristol context - 98 3.1: Irish neutrality - 99 3 3.2: The Treaty Ports - 101 3.3: Loyalists and Nationalists - 104 3.4: Fifth column fears - 107 3.5: The American Note - 110 3.6: Volunteers and emigrants - 111 3.7: Condolences and speeches - 113 3.8: The Republic -

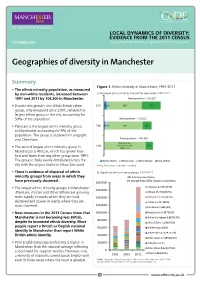

Geographies of Diversity in Manchester

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Manchester Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Manchester, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased between a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 1991 and 2011 by 104,300 in Manchester. Total population – 503,127 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 5% 2% 59% 33% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city, accounting for 59% of the population. Total population – 422,922 • Pakistani is the largest ethnic minority group 2001 2% 4% 74% 19% in Manchester accounting for 9% of the population. The group is clustered in Longsight and Cheetham. Total population – 432,685 85% (includes 1991 White Other and 15% • The second largest ethnic minority group in White Irish Manchester is African, which has grown four- fold and faster than any other group since 1991. The group is fairly evenly distributed across the White Other White Irish White British Non-White city with the largest cluster in Moss Side ward. Notes: Figures may not add due to rounding. • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 minority groups from areas in which they 2011 Census estimates (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. 180,000 • The largest ethnic minority groups in Manchester Pakistani 42,904 (73%) 160,000 (Pakistani, African and Other White) are growing African 25,718 (254%) more rapidly in wards where they are least 140,000 Chinese 13,539 (142%) clustered and slower in wards where they are Indian 11,417 (80%) 120,000 most clustered. -

Forecasting Sub-National Trends in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in the UK 2 3 A

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.20248382; this version posted April 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 Forecasting sub-national trends in COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the UK 2 3 A. de Figueiredo1,2 4 5 1 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, 6 UK. 7 2 Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, UK. 8 9 [email protected] 10 11 12 The rollout of COVID-19 vaccines has begun to at-risk populations around the world. It is currently 13 unclear whether rejection of the vaccine will pose challenges for achieving herd/community immunity 14 either through large-scale rejection or localised pockets. Here we predict uptake of the vaccine at 15 unprecedented spatial resolution across the UK using a large-scale survey of over 17,000 individuals. 16 Although the majority of the UK population would likely take the vaccine, there is substantial 17 heterogeneity in uptake intent across the UK. Large urban areas, including London and North West 18 England, females, Black or Black British ethnicities, and Polish-speakers are among the least accepting. 19 This study helps identify areas and socio-demographic groups where vaccination levels may not reach 20 those levels reQuired for herd immunity. Identifying clusters of non-vaccinators is extremely important 21 in the context of achieving herd immunity as vaccination “cold-spots” can amplify epidemic spread and 22 disproportionately increase vaccination levels required for herd protection. -

Central Scotland Regional Equality Council Limited

MULTI-AGENCY HATE RESPONSE STRATEGY (M.A.H.R.S.) QUARTER 1 - (2015/2016) INCIDENT REPORT April - June 2015 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 03 2. Results Agencies 03 Number of Incidents 04 - 05 Crime/Charges 05 Crimes Detection 06 Ethnicity of Victims 07 Ethnicity of Perpetrators 08 Crime Types 09 Locations 10 3. Summary 11 4. Conclusions 11 5. Recommendations 11 6. Appendices 12 - 13 * * * 2 1. INRODUCTION The following graphs and tables provide information associated with Hate Incidents as obtained from two agencies in the above mentioned quarter. 2. RESULTS Table 1(a) and Graph (1b) below shows that all of the incidents were reported by the police. No. of Incidents No. Agency Reported 1. Police Scotland 93 2. Central Scotland REC 0 3. Falkirk Council 0 4. Forth Valley College 0 5. Clackmannanshire Council 0 6. Stirling Council 0 7. NHS, Forth Valley 5 8. Victim Support 0 9. COPFS 0 10. Fire & Rescue Service 0 11. University of Stirling 0 Total Incidents 98 1 (a) Police Scotland NHS FV 1 (b) Notes Reports were received by Polish Scotland, Forth Valley College and NHS Forth Valley. One of the reports received from NHSW Forth Valley was from the previous quarter that was already included in those statistics It will not be included in the following report so it should only come to a total of 97. 3 Table 2 (a) and Graph 2 (b) below shows a breakdown on the number of Incidents. Area Hate Motive Clacks Falkirk Stirling Unknown Grand Total Disability 1 1 5 7 Disability, Sexuality 1 0 0 1 Race 12 29 21 62 Race, Religion/Faith 0 1 0 1 Religion/Faith 4 3 2 9 Sexuality 2 5 7 14 Sexuality, Race 1 1 0 1 Transgender 1 0 1 1 Unreasonable Behaviour 0 1 0 1 Grand Total 20 41 36 97 2 (a) 35 30 25 Clacks 20 Falkirk 15 10 Stirling 5 0 Race Race Disability Sexuality Sexuality Disability, Sexuality, Race, Behaviour Transgender Religion/Faith Religion/Faith Unreasonable 2 (b) Notes As Table (2a) shows, the highest amount of Incidents that occurred are again motivated by Race making up nearly 64% of all incidents. -

Patterns of Care Received by Women with Breast Cancer Living in Affluent and Deprived Areas

PATTERNS OF CARE RECEIVED BY WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER LIVING IN AFFLUENT AND DEPRIVED AREAS Una Margaret Macleod MB ChB, MRCGP Submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy To the University of Glasgow From the Department of General Practice November 2000 ProQuest Number: 13818957 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818957 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UK'VERSITY ' library TUe^fe 12139 c oPH \ This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my father Donaid B Macleod M.A. 16.10.1929- 16.1.1995 2 Abstract Breast cancer occurs less commonly in socio-economically deprived women than in affluent women. Following diagnosis however, deprived women have poorer survival rates from breast cancer. Previous research suggests that their poorer survival is not due to the stage of the cancer at time of presentation. If poorer outcomes are not due to more advanced stage of disease at time of presentation alternative explanations are that the difference may be due to variations in treatment or host response mechanisms or environmental factors.