Tobacco Use, Ethnicity and Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report

Scotland’s Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report Scotland’s Census 2021 – Ethnic Group Topic Report Table of Contents 1. Main Points .......................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 3. Background ......................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Ethnic group in the census .............................................................................. 5 3.2 The 2011 Ethnic Group and National Identity Questions ................................. 6 3.3 Questions in other UK 2011 Censuses............................................................ 8 3.4 Alternative sources .......................................................................................... 9 4. Understanding user need for 2021 ...................................................................... 9 5. 2017 Question Testing ....................................................................................... 10 5.1 Cognitive testing ............................................................................................ 11 5.2 Quantitative testing ........................................................................................ 15 6. Next Steps ......................................................................................................... 16 Annex A: 2017 Cognitive Test ................................................................................. -

Conclusion 60

Being Black, Being British, Being Ghanaian: Second Generation Ghanaians, Class, Identity, Ethnicity and Belonging Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah UCL PhD 1 Declaration I, Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Table of Contents Declaration 2 List of Tables 8 Abstract 9 Impact statement 10 Acknowledgements 12 Chapter 1 - Introduction 13 Ghanaians in the UK 16 Ghanaian Migration and Settlement 19 Class, status and race 21 Overview of the thesis 22 Key questions 22 Key Terminology 22 Summary of the chapters 24 Chapter 2 - Literature Review 27 The Second Generation – Introduction 27 The Second Generation 28 The second generation and multiculturalism 31 Black and British 34 Second Generation – European 38 US Studies – ethnicity, labels and identity 40 Symbolic ethnicity and class 46 Ghanaian second generation 51 Transnationalism 52 Second Generation Return migration 56 Conclusion 60 3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical concepts 62 Background and concepts 62 Class and Bourdieu: field, habitus and capital 64 Habitus and cultural capital 66 A critique of Bourdieu 70 Class Matters – The Great British Class Survey 71 The Middle-Class in Ghana 73 Racism(s) – old and new 77 Black identity 83 Diaspora theory and the African diaspora 84 The creation of Black identity 86 Black British Identity 93 Intersectionality 95 Conclusion 98 Chapter 4 – Methodology 100 Introduction 100 Method 101 Focus of study and framework(s) 103 -

Strategic Needs Assessment

Clackmannanshire and Stirling Strategic Plan Strategic Needs Assessment 2016 - 2019 Health and Social Care Partnership Table of Contents Executive Summary.......................................................................................................................................5 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................7 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................................................7 1.2 What is a Strategic Needs Assessment ....................................................................................... 10 1.3 Identified Gaps............................................................................................................................11 2 Population................................................................................................................................................11 2.1 Current Population......................................................................................................................11 2.1.1 Ethnic Origin................................................................................................................................16 2.1.2 Religion........................................................................................................................................16 2.1.3 Sexual Orientation ......................................................................................................................17 -

Central Scotland Regional Equality Council Limited

MULTI-AGENCY HATE RESPONSE STRATEGY (M.A.H.R.S.) QUARTER 1 - (2015/2016) INCIDENT REPORT April - June 2015 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 03 2. Results Agencies 03 Number of Incidents 04 - 05 Crime/Charges 05 Crimes Detection 06 Ethnicity of Victims 07 Ethnicity of Perpetrators 08 Crime Types 09 Locations 10 3. Summary 11 4. Conclusions 11 5. Recommendations 11 6. Appendices 12 - 13 * * * 2 1. INRODUCTION The following graphs and tables provide information associated with Hate Incidents as obtained from two agencies in the above mentioned quarter. 2. RESULTS Table 1(a) and Graph (1b) below shows that all of the incidents were reported by the police. No. of Incidents No. Agency Reported 1. Police Scotland 93 2. Central Scotland REC 0 3. Falkirk Council 0 4. Forth Valley College 0 5. Clackmannanshire Council 0 6. Stirling Council 0 7. NHS, Forth Valley 5 8. Victim Support 0 9. COPFS 0 10. Fire & Rescue Service 0 11. University of Stirling 0 Total Incidents 98 1 (a) Police Scotland NHS FV 1 (b) Notes Reports were received by Polish Scotland, Forth Valley College and NHS Forth Valley. One of the reports received from NHSW Forth Valley was from the previous quarter that was already included in those statistics It will not be included in the following report so it should only come to a total of 97. 3 Table 2 (a) and Graph 2 (b) below shows a breakdown on the number of Incidents. Area Hate Motive Clacks Falkirk Stirling Unknown Grand Total Disability 1 1 5 7 Disability, Sexuality 1 0 0 1 Race 12 29 21 62 Race, Religion/Faith 0 1 0 1 Religion/Faith 4 3 2 9 Sexuality 2 5 7 14 Sexuality, Race 1 1 0 1 Transgender 1 0 1 1 Unreasonable Behaviour 0 1 0 1 Grand Total 20 41 36 97 2 (a) 35 30 25 Clacks 20 Falkirk 15 10 Stirling 5 0 Race Race Disability Sexuality Sexuality Disability, Sexuality, Race, Behaviour Transgender Religion/Faith Religion/Faith Unreasonable 2 (b) Notes As Table (2a) shows, the highest amount of Incidents that occurred are again motivated by Race making up nearly 64% of all incidents. -

The Changing Ethnic Profiles of Glasgow and Scotland, and the Implications for Population Health

The changing ethnic profiles of Glasgow and Scotland, and the implications for population health David Walsh September 2017 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks are due to a number of people who have helped with this report and the work that lies behind it. In particular, I would like to thank Duncan Buchanan (ISD Scotland) and Anne Douglas (University of Edinburgh) for their time and patience in various discussions of the SHELS research, as well as for highly useful comments on an earlier draft of the report. I am also extremely grateful to Jackie Erdman (NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde), Colin Fischbacher (ISD Scotland), Gerry McCartney (NHS Health Scotland), Paul Norman (University of Leeds) and Bruce Whyte (GCPH) for additional, and very helpful, comments. Thanks also to Jon Hunter (Scottish Government) for the provision of, and the permission to use, the data reproduced in Figures 8 & 9. Finally, the usual thanks are due to Joe Crossland (GCPH) for invaluable assistance in publishing the report. Contact David Walsh Public Health Programme Manager Glasgow Centre for Population Health Tel: 0141 330 2747 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gcph.co.uk Twitter: @theGCPH 2 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 2 Contact .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................ -

Community Case Study: Dundee, Scotland

1 Community Case Study: Dundee, Scotland Total population Dundee city Scotland 2011 2011 Total Population: 2011 145570 5254800 Median Age 38 41 Main ethnic groups Dundee city Scotland 2011 % 2011 % White British 131,610 90 4,862,787 92.5 White Other 6850 4.7 221,620 4.2 Mixed or Multiple Ethnic Groups 685 0.5 19815 0.4 Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British 5838 4.0 140678 2.7 African 1170 0.8 29638 0.6 Caribbean or Black 269 0.2 6540 0.1 Other ethnic groups 846 0.6 14325 0.3 2 Total number of Muslims and percentage at 2011 census Overall Muslim Population Population Change All People Change Muslims 2001 2011 2001-2011 % 2001 % of 2011 % of population 2001-2011 % change population change 145,663 147,268 1,605 1.1 2,879 2.0 3,875 2.6 996 34.6 3 Ethnic breakdown of Muslim groups at census I have not been able to obtain data for Dundee because the census search engine doesn’t work on Excel for Mac (or at least my version). The following information is for Scotland, obtained from Scottish Muslims in numbers published by the Alwaleed Centre, University of Edinburgh Muslims Muslim Population Change Proportion of overall %change 2001 % 2011 % 2001- 2011 % change White Total 3,401 8.0 5,983 7.80 2,582 75.92 4.15 White: Scottish 1,151 2.70 2,501 3.26 1,350 117.29 2.17 White: Other British 353 0.83 694 0.90 341 96.60 0.55 White: Irish 35 0.08 61 0.08 26 74.29 0.04 White: Gypsy/Traveller - - 25 0.03 - - - White: Polish - - 130 0.17 - - - Other White 1,862 4.38 2,572 3.35 710 38.13 1.14 Any Mixed Background 1,367 3.21 1,342 1.75 -25 -1.83 -0.04 Asian Total 33,626 79.01 54,870 71.50 21,244 63.18 34.17 Indian 892 2.10 1,954 2.55 1,062 119.06 1.71 Pakistani 28,353 66.62 44,858 58.46 16,505 58.21 26.55 Bangladeshi 1,669 3.92 3,053 3.98 1,384 82.92 2.23 Other South Asian 2,674 6.28 4,664 6.08 1,990 74.42 3.20 Chinese 38 0.09 341 0.44 303 797.37 0.49 Black Total 1,059 2.49 5,380 7.01 4,321 408.03 6.95 Caribbean 15 0.04 31 0.04 16 106.67 0.03 African 946 2.22 5,051 6.58 4,105 433.93 6.60 4 Contd. -

All Figures and Background Data

Figure 1.1: Estimated population of Scotland, actual and projected1, 1951-2037 6,000 2014 5,000 4,000 Actual Projected 1 3,000 Persons (1,000s) 2,000 1,000 0 1951 1955 1959 1963 1967 1971 1975 1979 1983 1987 1991 1995 1999 2003 2007 2011 2015 2019 2023 2027 2031 2035 Footnote Year at 30 June 1) 2012-based projections. © Crown Copyright 2015 Figure 1.2: Natural change1 and net migration2, 1951-2014 50 40 Natural change1 30 20 10 0 Persons (1,000s)Persons -10 -20 -30 Net migration2 -40 -50 1951 1956 1961 1966 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 2001 2006 2011 Footnotes 1) Births minus deaths. 2) Inward minus outward migration. Year © Crown Copyright 2015 Figure 1.3: Estimated population by age and sex, 30 June 2014 90+ 84 Males Females 78 72 66 60 54 48 Age 42 36 30 24 18 12 6 0 50 40 30 20 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 Persons (1,000s) © Crown Copyright 2015 Figure 1.4: The changing age structure of Scotland’s population, 2004-2014 1,400 +13% -11% 1,200 2004 +10% 2014 1,000 -3% +17% 800 Persons (1,000s)Persons 600 +17% 400 200 0 0-15 16-29 30-44 45-59 60-74 75 + Age group © Crown Copyright 2015 Figure 1.6: Births and deaths, actual1 and projected2, Scotland, 1951-2037 120 2012 100 Births Deaths 80 60 Persons (1,000s)Persons 40 Actual1 Projected2 20 0 1951 1954 1957 1960 1963 1966 1969 1972 1975 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2013 2016 2019 2022 2025 2028 2031 2034 2037 Footnotes 1) Calendar year. -

4. Dundee and Angus College Equality Activities

Copies of this document can be provided in large text or Braille formats as required by contacting the Student Services Team on 01382 834834. Contents 1. Message from the Principal ................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Legislative Context .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 3.1 General and Specific Duties .......................................................................................................................................... 3 4. Dundee and Angus College Equality Activities ................................................................................................................... 5 4.1 History of Dundee College and Angus College Equality Activities ................................................................................ 5 4.2 Dundee and Angus College Equalities Actions.............................................................................................................. 6 4.2.1 RESPECT Campaign ................................................................................................................................................ 6 4.2.2 The Social Model of Disability ............................................................................................................................... -

April 2019 Pharmaceutical Care Services in NHS Fife 2019/20

Pharmaceutical Care Services in NHS Fife 2019/20 (April 2019) April 2019 Pharmaceutical Care Services in NHS Fife 2019/20 1 Pharmaceutical Care Services in NHS Fife 2019/20 (April 2019) CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. page 3 1 Introduction to NHS Fife Health Board Area .................................... page 4 2 Description of Current Pharmaceutical Services in NHS Fife ........ page 16 3 Description of Current General Medical Service Provision in NHS Fife .............................................................................................. page 31 4 Analysis of Pharmaceutical Needs within NHS Fife with Recommendations to Meet Identified Under Provision .................. page 32 5 Appendices ......................................................................................... page 34 Appendix 1a - Map of East Division of Health & Social Care Partnership by SIMD quintiles .................................................................... page 34 Appendix 1b - Levenmouth Locality Profile .............................................. page 35 Appendix 1c - Glenrothes Locality Profile ................................................. page 38 Appendix 1d - North East Fife Locality Profile .......................................... page 41 Appendix 1e - Map of West Division of Health & Social Care Partnership by SIMD quintiles .................................................................... page 44 Appendix 1f - Cowdenbeath Locality Profile ............................................ -

Languages Spoken in Aberdeen City

Languages spoken in Aberdeen City Briefing paper 2016/02 RESEARCH AND INFORMATION Research and Information Briefing Paper 2016/02 (Published April 2016) Languages spoken in Aberdeen City This is one in a series of briefing papers that has been produced by the Research and Information team. It is intended that these papers will be used by Council services and, where appropriate, our Community Planning partners to assist policy development and wider service delivery. Some papers, including this one, may be of interest to a wider audience. This paper looks at Languages spoken in Aberdeen City (including some information on Aberdeenshire for comparison). Available information on languages comes primarily from the Census which provides data on how well English is spoken by Aberdeen City’s population as well as what languages are used at home. The Census also provides additional information about the level of Gaelic language skills within Aberdeen City. Further information about languages used in Aberdeen City was provided by Aberdeen City Council translation services (InterTrans) and also by the Pupils Census. For more information on these issues, please contact: Research and Information Team Office of Chief Executive Aberdeen City Council 1st Floor, Old Town House Broad Street Aberdeen AB10 1FY 01224 523322 [email protected] Other briefing papers in this series have included the following topics: Population Report, Aberdeen City and Shire Population of Older People in Aberdeen Migrant Workers in Aberdeen City and Shire These papers, and other statistical reports, can be found in the ‘Stats and Facts’ section of the Aberdeen City Council website: www.aberdeencity.gov.uk/statsandfacts We value your comments/feedback and would appreciate if you could provide your comments on this paper by clicking the following link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/research-feedback-form 1 Summary English is the main language spoken in Aberdeen City. -

How Has Ethnic Diversitychanged in Scotland?

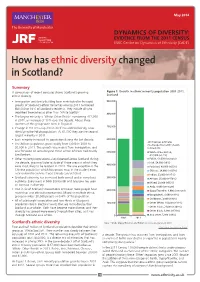

May 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) How has ethnic diversity changed in Scotland? Summary A comparison of recent censuses shows Scotland’s growing Figure 1. Growth in ethnic minority population 2001-2011, ethnic diversity. Scotland • Immigration and family-building have contributed to the rapid 900,000 growth of Scotland’s ethnic minorities who by 2011 numbered 850,000 or 16% of Scotland’s residents. They include all who described themselves as other than ‘White Scottish’. 800,000 • The largest minority is ‘White: Other British’ numbering 417,000 in 2011, an increase of 10% over the decade. About three quarters of this group were born in England. 700,000 • Change in the census question itself has added diversity, now identifying the Polish population. At 61,000 they are the second largest minority in 2011. • Each minority increased its population during the last decade. 600,000 2011 Census estimates • The African population grew rapidly from 5,000 in 2001 to (% change from 2001 shown 30,000 in 2011. This growth was mainly from immigration, and in brackets) was focussed on areas beyond those where Africans had mainly 500,000 White Other British, lived before. 417,000 (+12%) • Other minority populations also dispersed across Scotland during Polish, 61,000 (see note) the decade, growing faster outside of those areas in which they Irish, 54,000 (+9%) 400,000 were most likely to be resident in 2001. The one exception is the Pakistani, 49,000 (+55%) Chinese population which has grown most in the student areas Chinese, 34,000 (+107%) near universities where it was already concentrated. -

Taking Stock – Race Equality in Scotland

Runnymede Perspectives Taking Stock Race Equality in Scotland Edited by Nasar Meer, Smina Akhtar and Neil Davidson Runnymede: Intelligence Disclaimer This publication is part of the Runnymede Perspectives for a Multi-ethnic Britain series, the aim of which is to foment free and exploratory thinking on race, ethnicity and equality. The facts presented and views expressed in this publication are, however, those Runnymede is the UK’s of the individual authors and not necessariliy those of the leading independent thinktank Runnymede Trust. on race equality and race relations. Through high- ISBN: 978-1-909546-31-8 quality research and thought Published by Runnymede in May 2020, this document is leadership, we: copyright © Runnymede 2020. Some rights reserved. • Identify barriers to race Open access. Some rights reserved. The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of equality and good race its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. relations; The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone • Provide evidence to to access its content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any support action for social format, including translation, without written permission. change; This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons • Influence policy at all Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: levels. • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform the work; • You must give the original author credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.