Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Variation in Outcome of People Hospitalised During the First COVID

Open access Original research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048335 on 18 August 2021. Downloaded from Ethnic variation in outcome of people hospitalised during the first COVID-19 epidemic wave in Wales (UK): an analysis of national surveillance data using Onomap, a name- based ethnicity classification tool Daniel Rh Thomas ,1,2 Oghogho Orife ,1 Amy Plimmer,1 Christopher Williams,1 George Karani,2 Meirion R Evans,1 Paul Longley,3 Janusz Janiec,4 Roiyah Saltus,5 Ananda Giri Shankar6 To cite: Thomas DR, Orife O, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Plimmer A, et al. Ethnic Objective To identify ethnic differences in proportion variation in outcome of people positive for SARS- CoV-2, and proportion hospitalised, hospitalised during the first ► Secondary analysis of data obtained through routine proportion admitted to intensive care and proportion died COVID-19 epidemic wave national COVID-19 surveillance. in hospital with COVID-19 during the first epidemic wave in Wales (UK): an analysis ► Studies relying on clinician reported ethnicity con- of national surveillance in Wales. tain high proportions of missing and poor quality data using Onomap, a Design Descriptive analysis of 76 503 SARS- CoV-2 tests data. name- based ethnicity carried out in Wales to 31 May 2020. Cohort study of 4046 ► Using a proven name-based classifier, we were able classification tool. BMJ Open individuals hospitalised with confirmed COVID-19 between to assign ethnicity to nearly all participants. 2021;11:e048335. doi:10.1136/ 1 March and 31 May. In both analyses, ethnicity was While sensitivity and specificity of the classifier bmjopen-2020-048335 ► assigned using a name- based classifier. -

Scotland's Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report

Scotland’s Census 2021 Ethnic Group Topic Report Scotland’s Census 2021 – Ethnic Group Topic Report Table of Contents 1. Main Points .......................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 3. Background ......................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Ethnic group in the census .............................................................................. 5 3.2 The 2011 Ethnic Group and National Identity Questions ................................. 6 3.3 Questions in other UK 2011 Censuses............................................................ 8 3.4 Alternative sources .......................................................................................... 9 4. Understanding user need for 2021 ...................................................................... 9 5. 2017 Question Testing ....................................................................................... 10 5.1 Cognitive testing ............................................................................................ 11 5.2 Quantitative testing ........................................................................................ 15 6. Next Steps ......................................................................................................... 16 Annex A: 2017 Cognitive Test ................................................................................. -

Who Identifies As Welsh? National

November 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who identifies asWelsh? National identities and ethnicity in Wales Summary • In Wales, 1.8 million people identify only as Welsh (58% of • People born in Wales are more likely to report only a Welsh the population) and 218,000 identify as Welsh and British national identity (76%). People born in Oceania and North (7% of the population). America and the Caribbean are more likely to report only a Welsh national identity (14% and 10% respectively) than • Mixed ethnic groups are more likely to identify with only people born in England (8%). a Welsh national identity than all other ethnic minority groups, with the highest proportion being amongst the White and Black Caribbean (59%) group. Introduction Since devolution, the Welsh Government has sought to • Mixed groups are more likely to identify only as Welsh support a common Welsh national identity through the ‘One (47%) than mixed groups in England (46%) and Scotland Wales’ strategy. This has included, for example, strengthening (37%) identify as English or Scottish only. the place of ‘Wales in the World’ and continued support for 1 • The ethnic groups in Wales most likely to identify only as the Welsh language. The inclusion of a question on national British are Bangladeshi (64%), Pakistani (56%) and Black identity in the 2011 Census provides us with an opportunity Caribbean (41%). to examine how people living in Wales describe themselves. The Census shows that 58% of people living in Wales identify • Welsh only national identity is reported more for younger only as Welsh and a further 7% identify as Welsh and British.2 people aged 0 to 17 than those aged 18 or older. -

Equality Monitoring Report

Sheffield Hallam University - Equality Monitoring Report Introduction To meet the Public Sector Equality Duty, the government requires all Universities to make equality information available publicly. Adhering to the new Act, this report reflects the make-up of students and staff at Sheffield Hallam University. Four core equality indicators have been assessed: gender; age; ethnicity; disability. Where meaningful, information is disaggregated to show various study levels and intensity (mode). Given the various tiers of data included in the report, please refer to the annex for full descriptions of acronyms and groupings. Contents Page Part 1: Student Equality Indicators Section 1: Overall University Equality Indicators 2 1.1 University Size & Shape Overview 2 1.2 University Gender Profile 2 1.3 University Age Profile 3 1.4 University Ethnicity Profile 4 1.5 University Disability Profile 5 Section 2: Performance Measurements Using Equality Indicators 7 2.1 First Degree Attainment 7 2.2 Employment 9 2.3 Graduate Level Employment 12 Part 2: Staff Equality Indicators Section 3: Staff Equality Indicators 14 3.1 Staff Overview 14 3.2 Staff Gender Profile 14 3.3 Staff Age Profile 14 3.4 Staff Ethnicity Profile 15 3.5 Staff Disability Profile 16 Section 4: Applications for Staff Vacancies 17 4.1 Applications for Staff Vacancies - Overview 17 4.2 Applications for Staff Vacancies - Gender Profile 17 4.3Applications for Staff Vacancies - Age Profile 18 4.4 Applications for Staff Vacancies - Ethnicity Profile 19 4.5 Applications for Staff Vacancies -

Woodfuel Resource in Britain Appendices

WOODFUEL RESOURCE IN BRITAIN Part 2: APPENDICES H. McKay September 2003 1 WOODFUEL RESOURCE IN BRITAIN 1 2 3 4 5 6 A Bijlsma , G Bull , R Coppock , R Duckworth , L Halsall , J B Hudson , R J 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hudson , D Johnson , B Jones , M Lightfoot , E Mackie , A Mason , R 13 14 15 16 17 Matthews , H McKay , N Purdy , M Sendros , S Smith Research Contractors: Forestry Commission and Forestry Contracting Association 1 GIS Data Analyst, Forest Enterprise, (now Forestry Group), Forestry Commission 2 Woodland Surveys Officer, Forest Research, Forestry Commission 3 Systems Manager, Forest Enterprise; now on secondment to the Scottish Forestry Cluster 4 Consultant, Mathematical modelling and software engineer, Duckworth Consultants Ltd. 5 Systems Manager, Forest Enterprise, (now Forestry Group), Forestry Commission 6 Former Chief Executive and Research & Development Team Leader for the Forestry Contracting Association; now Hudson Consulting Ltd - Wood fuel and forestry consultants 7 Projects Manager, Research & Development Department, Forestry Contracting Association 8 Analyst/Programmer, Forest Research, Forestry Commission 9 Head of Technical Development Branch, Forest Research, Forestry Commission 10 Consultant software engineer, Environ – IT Ltd 11 Researcher, Research & Development Department, Forestry Contracting Association 12 Software Development Consultant 13 Research Programme Leader, Forest Research, Forestry Commission 14 Principal Advisor, Policy and Practice Division, (now Forestry Group), Forestry Commission 15 Marketing Officer, Forest Enterprise 16 Researcher, Research & Development Department, Forestry Contracting Association 17 Head of Woodland Surveys, Forest Research, Forestry Commission 2 Appendices Appendix 1 Successful Bioenergy Capital Grant Scheme projects Appendix 2 Principal producers and users Appendix 3 Development of allometric relationships for principal tree components in British forest stands Appendix 4 Development of models of tree size distributions Appendix 5 Data and parameters in BSORT model. -

Ethnic Data Collection in the EU: Can't Seem to Find The

Ethnic data collection in the EU: can’t seem to find the way Lilla Farkas, race ground coordinator, European Network of legal experts on gender equality and non-discrimination,, [email protected] Reporting flurry 1. EDI Report 2014 - OSF & ENAR 2. European Commission 1. Ethnic Data Report and Handbook update 2016 2. Guidance note on hate crimes November 2018 3. FRA: 1. EU MIDIS 2016, 2. hate crime map, 3. PAD November 2018 4. ECRI: general recommendations hate crime, hate speech, Afrophobia EU context - political • Agenda setting & multilevel governance: allies, foes and competitors • Equality data: a problem for many - coalition with other grounds? • Recognised & non-recognised racialised groups - coalition? • European silence on race - including among the racialised groups! • Wallerstein and Balibar 1991: race and gender within class • The Holocaust prism • Migrant and Roma integration frames EU context - jurisprudential 1. The meaning of racial or ethnic origin under EU law 2017: historically contingent 2. ‘racial’ fragmentation: no dominant racial group 3. race reified in case law • = skin colour? as if racial minorities did not have an identity • Timishev v Russia, • Biao v Denmark - Islamophobic undertone • Feryn - Moroccans, xenophobia, Islamophobia or Afrophobia? • CHEZ and Jyske Finans: only ethnicity in RED? ICERD mis-used? • Attrey in CMLR, • Farkas in EADLR Key issues: categorization I. 1. Data on racial origin is seldom collected based on self- identification. 2. How to categorise descent: geographic origin and cultural/religious/linguistic traditions 3. How to link descent with skin colour 4. 30% of PAD Muslim - Islamophobia in Europe Categories: Maghreb, Sub-Saharan African, Other African? Categorization II. -

Draft V0.1 7/11/12

Sheffield 2012: JSNA Demographics Background Data Report DRAFT V0.1 7/11/12 Sheffield 2012: JSNA Demographics Background Data Report Data to support the refresh of JSNA 2012 The report covers Ann Richardson Public Health Analysis Team Sheffield population trends NHS Sheffield Projections (overall and by age groups) 722 Prince of Wales Road Population distribution across the city Sheffield Ethnic populations S9 4EX Tel: 0114 305 1250 E-mail: ann.richardson @sheffieldpct.nhs.uk Date: 5 November 2012 Ref: 2012 (10) V1.0 Public Health Analysis Team (AR) Page 1 of 23 Sheffield 2012: JSNA Demographics Background Data Report Title Sheffield 2012: JSNA Demographics Background Data Report Reference Status (Draft / Issued) DRAFT Version 0.1 Date Created 05.11.12 Approved By Commissioned by Jeremy Wight Audience Distribution FOI Category No restrictions Author Ann Richardson, Public Health Analysis Team Owner (if different) Amendment History Review date Comments TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Key Points ............................................................................................................................. 3 2 Introduction............................................................................................................................ 5 3 Sheffield Population Trends .................................................................................................. 5 3.1 Sheffield Clinical Commissioning Group (SCCG) Resident and Registered ................. 6 3.2 Age and Sex Structure ................................................................................................. -

2011 Census Key Statistics Ethnic Group

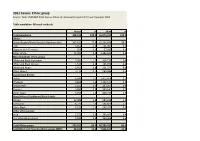

2011 Census: Ethnic group Source: Table KS201EW 2011 Census Office for National Statistics © Crown Copyright 2012 Table population: All usual residents Bristol % E&W % Total population 428,234 100.0 56,075,912 100.0 White: British/English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish 333,432 77.9 45,134,686 80.5 Irish 3,851 0.9 531,087 0.9 Gypsy or Irish Traveller 359 0.1 57,680 0.1 Other White 21,950 5.1 2,485,942 4.4 Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black Caribbean 7,389 1.7 426,715 0.8 White and Black African 1,533 0.4 165,974 0.3 White and Asian 3,402 0.8 341,727 0.6 Other Mixed 3,114 0.7 289,984 0.5 Asian/Asian British: Indian 6,547 1.5 1,412,958 2.5 Pakistani 6,863 1.6 1,124,511 2.0 Bangladeshi 2,104 0.5 447,201 0.8 Chinese 3,886 0.9 393,141 0.7 Other Asian 4,255 1.0 835,720 1.5 Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: African 12,085 2.8 989,628 1.8 Caribbean 6,727 1.6 594,825 1.1 Other Black 6,922 1.6 280,437 0.5 Other ethnic group: Arab 1,272 0.3 230,600 0.4 Any other ethnic group 2,543 0.6 333,096 0.6 Total White groups 359,592 84.0 48,209,395 86.0 Total Black and minority ethnic groups (BME) 68,642 16.0 7,866,517 14.0 2011 Census: Ethnic group (detailed) Source: Table QS211EW 2011 Census Office for National Statistics © Crown Copyright 2012 All usual residents Note: This table expands the standard 18 ethnic group response categories. -

New Build Homes, Flood Resilience and Environmental Justice – Current and Future Trends Under Climate Change Across England and Wales

New build homes, flood resilience and environmental justice – current and future trends under climate change across England and Wales Viktor Rözer and Swenja Surminski November 2020 Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy Working Paper No. 381 ISSN 2515-5709 (Online) Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Working Paper No. 353 ISSN 2515-5717 (Online) The Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy (CCCEP) was established by the University of Leeds and the London School of Economics and Political Science in 2008 to advance public and private action on climate change through innovative, rigorous research. The Centre is funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council. Its third phase started in October 2018 with seven projects: 1. Low-carbon, climate-resilient cities 2. Sustainable infrastructure finance 3. Low-carbon industrial strategies in challenging contexts 4. Integrating climate and development policies for ‘climate compatible development’ 5. Competitiveness in the low-carbon economy 6. Incentives for behaviour change 7. Climate information for adaptation More information about CCCEP is available at www.cccep.ac.uk The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment was established by the London School of Economics and Political Science in 2008 to bring together international expertise on economics, finance, geography, the environment, international development and political economy to create a world-leading centre for policy-relevant research and training. The Institute is funded by the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment and a number of other sources. It has 11 broad research areas: 1. Climate change adaptation and resilience 2. -

Our History: 40 Years of Alzheimer's Society

Our history: 40 years of Alzheimer’s Society years 402019 In 2019 Alzheimer’s Society will celebrate 40 years of improving the lives of people affected by dementia, through delivering care, campaigning for a fairer society and driving groundbreaking research. We will use this opportunity to reflect on how far we have come and the changes we have made, whilst recognising there is still much to do until we have a world without dementia. As we look back on 40 years of achievements, we will also highlight how those achievements have laid the foundations for our current strategy, The New Deal on Dementia, and how they complement the three pillars of the strategy. The new The new The new deal on deal on deal on Support Society Research Fundraising 1979 A radio broadcast by Professor Davison on his research into Alzheimer’s disease prompted Cora Phillips, a former carer, to contact him to set up a charity.1 Professor Davison put Cora in touch with Professor Gordon Wilcock who had contacted him about the same suggestion. From then a small group of passionate and determined people who shared an ambition to make life better for carers of people living with dementia united to formed the ‘Alzheimer’s Disease Society’.2 The first Steering Committee took place on 6 November with official charity status commencing on 19 December 1979.3 Meanwhile, Morella Fisher, an ex-carer was interviewed in ‘The Observer’ and her article on 2 December entitled ‘The Sad Quiet Epidemic’ resulted in several hundred letters including one from Cora Phillips inviting her to join the Steering Committee. -

Undergraduate Application Form

UNDERGRADUATE APPLICATION FORM Course Details Course Title:………………………………………………….. Year of entry:…………… Mode of Study: Full-time Your Details Title: First/Given Name(s)/ Last/Family Name: Date of Birth: ...................... Gender: Female/Male (please circle) Country of Birth: ................. Nationality: ...................................... Do you require a Visa to study in the UK? Yes / No (please circle) Passport Number: Have you ever had an application for a UK Visa refused in the last 5 years? Yes / No (If you have answered ‘Yes’ to this question the University may contact you for further information) Correspondence/ term-time address: Home address (if different) Country: Country: Postcode/Zipcode: Postcode/Zipcode: Telephone No: Telephone No: Mobile No: .............................................................. E-mail address: ....................................................... Skype address: ....................................................... Agent name (if applicable):………………………. Vice-Chancellor: Professor John Last Page | 1 Other Information How did you hear about the course at Norwich? .............................................................................. Have you applied to any other courses through UCAS this year? Yes / No (please circle) Education and Employment Higher/Tertiary Education: Please include all Further and Higher Education courses, including your current course, if appropriate. Qualification Subject Classification Name of Institution Dates /Level or grade (From / To) e.g. BA Degree Secondary -

Who Feels Scottish? National Identities and Ethnicity in Scotland

August 2014 DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Who feels Scottish? National identities and ethnicity in Scotland Summary • 83% of Scotland’s residents feel Scottish. • About 25% of Scotland’s residents born outside Scotland • 61% of Scotland’s residents identify as being of White do feel Scottish, and this is no less for those from South Scottish ethnicity and feel Scottish is their only national and East Asia, Africa and the Middle East, than it is for identity. A further 22% are from other ethnic groups and those born in England or other parts of Europe. About a feel they have a Scottish national identity, or are White third of Scotland’s residents born in North America, the Scottish whose Scottishness is combined with British or Old Commonwealth and Western Europe feel Scottish. other national identities. • The Polish ethnic group, who have recently had the • Catholics, Protestants and those of no religion share highest migration rates into Scotland, expressed most similar levels of commitment to a Scottish only national affiliation to a non-UK identity only (80%). identity, while two-thirds of Muslims in Scotland identify • For other groups, including Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, as Scottish or British. Africans, Indians and Chinese, British only was chosen • The ‘White: Other British’ are the largest ethnic minority in as frequently as Scottish only. This perhaps reflects the Scotland, and the ethnic group least likely to feel Scottish emphasis on Britishness in citizenship regulations, and national identity (11% feel Scottish, with or without other was also found in England where minorities identified identities).