2004 V03 03 Wu H P005.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

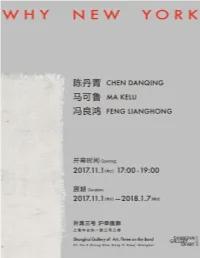

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

2000.541Ekxbtha

Memo to the Planning Commission DIRECTOR’S REPORT: AUGUST 31, 2017 Date: August 21, 2017 Case No.: 2000.541EKXBCTHA Project Address: 350 BUSH STREET Zoning: C-3-O (Downtown-Office) 250-S Height and Bulk District Block/Lot: 0269/028 Project Sponsor: Daniel Frattin Reuben, Junius & Rose One Bush Street, Suite 600 San Francisco, CA 94104 Staff Contact: Christy Alexander – (415) 575-8724 [email protected] Recommendation: Informational Only BACKGROUND10 On November 1, 2001, the Planning Commission approved Case No. 2000.541EKXBCTHA for a newly constructed 19-story office building addition to the existing Mining Exchange Building at 350 Bush Street which is located between Montgomery Street and Kearny Street downtown. The project includes 20,400 sf of retail space in two galleria levels and 344,540 sf of office space. Pursuant to Planning Code Section 429, the Project required a public art component valued at an amount equal to one percent of the hard construction costs for the Project as determined by the Director of the Department of Building Inspection. The Project Sponsor has commissioned two artists to provide on-site public art to satisfy this requirement. CURRENT PROPOSAL The artists selected for the public art installations at 350 Bush Street are Zhan Wang and Christopher Brown. As discussed in his biography (attached), Mr. Wang is a Beijing-born sculptor who was a sculpture major at the China Central Academy of Fine Art. His work has appeared in museum exhibitions at the Shanghai Pujiang OCT Ten Year Public Art Project, Shanghai; Mori Art Museum, Tokyo; Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, Shanghai; Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; the Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee; National Museum of China, Beijing; and the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Innovation Und Wandel Durch Chinas Heimgekehrte Akademiker?

Reverse Brain Drain: Innovation und Wandel durch Chinas heimgekehrte Akademiker? Eine Studie zum Einfluss geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlicher Rückkehrer am Beispiel chinesischer Eliteuniversitäten Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg im Promotionsfach Sinologie vorgelegt von Birte Klemm Hamburg, 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda Datum der Disputation: 14. August 2018 游学, 明时势,长志气,扩见闻,增才智, 非游历外国不为功也. 张之洞 1898 年《劝学篇·序》 Danksagung Ohne die Unterstützung einer Vielzahl von Menschen wäre diese Dissertation nicht zustande ge- kommen. Mein besonderer Dank gilt dem Betreuer dieser Arbeit, Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich, für seine große Hilfe bei den empirischen Untersuchungen und die wertvollen Ratschläge bei der Erstellung der Arbeit. Für die Zweitbegutachtung möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei Frau Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda bedanken. In der Konzeptionsphase des Projekts haben mich meine ehemaligen Kolleginnen und Kollegen am GIGA Institut für Asien-Studien, vor allem Prof. Dr. Thomas Kern, mit fachkundigen Ge- sprächen unterstützt. Ein großes Dankeschön geht überdies an Prof. Dr. Wang Weijiang und seine ganze Familie, an Prof. Dr. Chen Hongjie, Prof. Dr. Zhan Ru und Prof. Dr. Shen Wenzhong, die mir während meiner empirischen Datenerhebungen in Peking und Shanghai mit überwältigender Gastfreundschaft und Expertise tatkräftig zur Seite standen und viele Türen öffneten. An dieser Stelle möchte ich auch die zahlreichen Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmern der empiri- schen Umfragen dieser Studie würdigen. Hervorheben möchte ich die Studierenden der Beida und Fudan, die mir sehr bei der Verteilung der Fragebögen halfen und mir vielfältige Einblicke in das chinesische Hochschulwesen sowie studentische und universitäre Leben ermöglichten. -

Art and China's Revolution

: january / february 9 January/February 2009 | Volume 8, Number 1 Inside Special Feature: The Phenomenon of Asian Biennials and Triennials Artist Features: Yang Shaobin, Li Yifan Art and the Cultural Revolution US$12.00 NT$350.00 6 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2009 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 32 4 Contributors Autumn 2008 Asian Biennials 6 Premature Farewell and Recycled Urbanism: Guangzhou Triennial and Shanghai Biennale in 2008 Hilary Tsiu 16 Post-West: Guangzhou Triennial, Taipei Biennial, and Singapore Biennale Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker Contemporary Asian Art and the Phenomenon of the Biennial 30 Introduction 54 Elsa Hsiang-chun Chen 32 Biennials and the Circulation of Contemporary Asian Art John Clark 41 Periodical Exhibitions in China: Diversity of Motivation and Format Britta Erickson 47 Who’s Speaking? Who’s Listening? The Post-colonial and the Transnational in Contestation and the Strategies of the Taipei Biennial and the Beijing International Art Biennale Kao Chien-hui 54 Contradictions, Violence, and Multiplicity in the Globalization of Culture: The Gwangju Biennale 78 Sohl Lee 61 The Imagined Trans-Asian Community and the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale Elsa Hsiang-chun Chen Artist Features 67 Excerpts fom Yang Shaobin’s Notebook: A Textual Interpretation of X-Blind Spot Long March Writing Group 78 Li Yifan: From Social Archives to Social Project Bao Dong Art During the Cultural Revolution 94 84 Art and China’s Revolution Barbara Pollack 88 Zheng Shengtian and Hank Bull in Conversation about the Exhibition Art and China’s Revolution, Asia Society, New York 94 Red, Smooth, and Ethnically Unified: Ethnic Minorities in Propaganda Posters of the People’s Republic of China Micki McCoy Reviews 101 Chen Jiagang: The Great Third Front Jonathan Goodman 106 AAA Project: Review of A-Z, 26 Locations to Put Everything 101 Melissa Lam 109 Chinese Name Index Yuan Goang-Ming, Floating, 2000, single-channel video, 3 mins. -

James Cox Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JAMES COX Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:10 Nov 2009 Duration: about 1 hr 27 mins Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): I would love for you to talk a little bit about Grand Central Gallery, what it represented, whom it represented, your impressions about the exhibition, and how relationships were developed. You can tell any stories you want to tell. To begin, can you talk a little bit about Grand Central Gallery, how it was positioned and how you came upon these artists? James Cox (JC): I came to New York in 1976, and the reason my wife and I came was that I got a job, which is always a wonderful opportunity. I was 30 years old. I met my wife in Oklahoma City when we were in college together. Her father was an artist who showed in Chicago, New York, and Santa Fe. The New York gallery that represented him was the Grand Central Gallery. He was very familiar with the staff but more importantly he was familiar with the first Director of Grand Central Galley, who founded the gallery in 1922. He had been director for 56 years and was ready to retire. My father-in-law kept saying, ‘You really ought to go to New York and get in touch with the board; let them know that you are available…’, and so on. So I did that. I was very lucky to be hired. In brief, the gallery was set up to showcase American art, and was backed up by prominent American businessman including very major names in business, banking, and law. -

China As an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20Th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni

China as an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni 1 China as an Issue is an ongoing lecture series orga- nized by the Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum since 2018. Chinese scholars are invited to discuss topics related to China or the world, as well as foreign schol- ars to speak about China or international questions in- volving the subject of China. Through rigorous scruti- nization of a specific issue we try to avoid making generalizations as well as the parochial tendency to reject extraterritorial or foreign theories in the study of domestic issues. The attempt made here is not only to see the world from a local Chinese perspective, but also to observe China from a global perspective. By calling into question the underlying typology of the inside and the outside we consider China as an issue requiring discussion, rather than already having an es- tablished premise. By inviting fellow thinkers from a wide range of disciplines to discuss these topics we were able to negotiate and push the parameters of art and stimulate a discourse that intersects the arts with other discursive fields. The idea to publish the first volume of China as An Issue was initiated before the rampage of the coron- avirus pandemic. When the virus was prefixed with “China,” we also had doubts about such self-titling of ours. However, after some struggles and considera- tion, we have increasingly found the importance of 2 discussing specific viewpoints and of clarifying and discerning the specific historical, social, cultural and political situations the narrator is in and how this helps us avoid discussions that lack direction or substance. -

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins In

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins in Experimental Photography from China Xavier Ortells-Nicolau Directors de tesi: Dr. Carles Prado-Fonts i Dr. Joaquín Beltrán Antolín Doctorat en Traducció i Estudis Interculturals Departament de Traducció, Interpretació i d’Estudis de l’Àsia Oriental Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 ii 工地不知道从哪天起,我们居住的城市 变成了一片名副其实的大工地 这变形记的场京仿佛一场 反复上演的噩梦,时时光顾失眠着 走到睡乡之前的一刻 就好像门面上悬着一快褪色的招牌 “欢迎光临”,太熟识了 以到于她也真的适应了这种的生活 No sé desde cuándo, la ciudad donde vivimos 比起那些在工地中忙碌的人群 se convirtió en un enorme sitio de obras, digno de ese 她就像一只蜂后,在一间屋子里 nombre, 孵化不知道是什么的后代 este paisaJe metamorfoseado se asemeja a una 哦,写作,生育,繁衍,结果,死去 pesadilla presentada una y otra vez, visitando a menudo el insomnio 但是工地还在运转着,这浩大的工程 de un momento antes de llegar hasta el país del sueño, 简直没有停止的一天,今人绝望 como el descolorido letrero que cuelga en la fachada de 她不得不设想,这能是新一轮 una tienda, 通天塔建造工程:设计师躲在 “honrados por su preferencia”, demasiado familiar, 安全的地下室里,就像卡夫卡的鼹鼠, de modo que para ella también resulta cómodo este modo 或锡安城的心脏,谁在乎呢? de vida, 多少人满怀信心,一致于信心成了目标 en contraste con la multitud aJetreada que se afana en la 工程质量,完成日期倒成了次要的 obra, 我们这个时代,也许只有偶然性突发性 ella parece una abeja reina, en su cuarto propio, incubando quién sabe qué descendencia. 能够结束一切,不会是“哗”的一声。 Ah, escribir, procrear, multipicarse, dar fruto, morir, pero el sitio de obras sigue operando, este vasto proyecto 周瓒 parece casi no tener fecha de entrega, desesperante, ella debe imaginar, esto es un nuevo proyecto, construir una torre de Babel: los ingenieros escondidos en el sótano de seguridad, como el topo de Kafka o el corazón de Sión, a quién le importa cuánta gente se llenó de confianza, de modo que esa confianza se volvió el fin, la calidad y la fecha de entrega, cosas de importancia secundaria. -

Download the Allure of Matter Exhibition Guide

EXHIBITION GUIDE WINTER/SPRING 2020 1 FOURTH FLOOR THIRD FLOOR SECOND FLOOR FIRST FLOOR GALLERY ENTRANCE OFFICES (GALLERY STAFF ONLY) EXHIBITIONS LEGEND THE ALLURE OF MATTER RESTROOM WATER FOUNTAIN BHUTAN: A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY ELEVATOR COAT/BAG CHECK CATALOG PICK-UP 1 FOURTH FLOOR THIRD FLOOR SECOND FLOOR Liu Jianhua, Black Flame, 2017, Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA. ON VIEW: FIRST FLOOR GALLERY ENTRANCE OFFICES at Wrightwood 659 (GALLERY STAFF ONLY) February 7–May 2, 2020 and EXHIBITIONS LEGEND at Smart Museum of Art The University of Chicago THE ALLURE OF MATTER RESTROOM 5550 S. Greenwood Avenue | Chicago, IL 60637 WATER FOUNTAIN BHUTAN: February 7–May 3, 2020 A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY ELEVATOR COAT/BAG CHECK CATALOG PICK-UP 2 Everyday Materials, Radically Reinvented. Gu Dexin, Untitled, 1989, Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA. NATIONAL TOUR Los Angeles County Museum of Art June 2, 2019–January 5, 2020 Smart Museum of Art and Wrightwood 659 February 7–May 3, 2020 Seattle Art Museum June 25–September 13, 2020 Peabody Essex Museum November 14, 2020–February 21, 2021 The national tour of this exhibition is supported by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. The Allure of Matter is co-organized by the Smart Museum of Art with Wrightwood 659 and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Seattle Art Museum, and the Peabody Essex Museum. The exhibition is curated by Wu Hung, Smart Museum Adjunct Curator, Harrie A. Vanderstappen Distinguished Service Professor of Art History, and Director of the Center for the Art of East Asia at the University of Chicago, with Orianna Cacchione, Smart Museum Curator of Global Contemporary Art.