China As an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20Th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Pollen Influx Data from Lake Baiyangdian, China

Quaternary Science Reviews 37 (2012) 81e91 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Pollen source areas of lakes with inflowing rivers: modern pollen influx data from Lake Baiyangdian, China Qinghai Xu a,b,*, Fang Tian a, M. Jane Bunting c, Yuecong Li a, Wei Ding a, Xianyong Cao a, Zhiguo He a a College of Resources and Environment Science, and Hebei Key Laboratory of Environmental Change and Ecological Construction, Hebei Normal University, East Road of Southern 2nd Ring, Shijiazhuang 050024, China b National Key Laboratory of Western China’s Environmental System, Ministry of Education, Lanzhou University, Southern Tianshui Road, Lanzhou 730000, China c Department of Geography, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull HU6 7RX, UK article info abstract Article history: Comparing pollen influx recorded in traps above the surface and below the surface of Lake Baiyangdian Received 30 April 2011 in northern China shows that the average pollen influx in the traps above the surface is much lower, at À À À À Received in revised form 1210 grains cm 2 a 1 (varying from 550 to 2770 grains cm 2 a 1), than in the traps below the surface 15 January 2012 À À À À which average 8990 grains cm 2 a 1 (ranging from 430 to 22310 grains cm 2 a 1). This suggests that Accepted 19 January 2012 about 12% of the total pollen influx is transported by air, and 88% via inflowing water. If hydrophyte Available online 17 February 2012 pollen types are not included, the mean pollen influx in the traps above the surface decreases to À À À À À À 470 grains cm 2 a 1 (varying from 170 to 910 grains cm 2 a 1) and to 5470 grains cm 2 a 1 in the traps Keywords: À2 À1 Pollen assemblages below the surface (ranging from 270 to 12820 grains cm a ), suggesting that the contribution of Pollen influx waterborne pollen to the non-hydrophyte pollen assemblages in Lake Baiyangdian is about 92%. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 © Copyright by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The How and Why of Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China by Jonathan Stanhope Bell Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Chair China’s urban landscape has changed rapidly since political and economic reforms were first adopted at the end of the 1970s. Redevelopment of historic city centers that characterized this change has been rampant and resulted in the loss of significant historic resources. Despite these losses, substantial historic neighborhoods survive and even thrive with some degree of integrity. This dissertation identifies the multiple social, political, and economic factors that contribute to the protection and preservation of these neighborhoods by examining neighborhoods in the cities of Beijing and Pingyao as case studies. One focus of the study is capturing the perspective of residential communities on the value of their neighborhoods and their capacity and willingness to become involved in preservation decision-making. The findings indicate the presence of a complex interplay of public and private interests overlaid by changing policy and economic limitations that are creating new opportunities for public involvement. Although the Pingyao case study represents a largely intact historic city that is also a World Heritage Site, the local ii focus on tourism has disenfranchised residents in order to focus on the perceived needs of tourists. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

News China March. 13.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 3 March 2013 Rs. 10.00 The first session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) opens at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China on March 5, 2013. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei meets Indian Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Cheng Guoping , on behalf Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid in New Delhi on of State Councilor Dai Bingguo, attends the dialogue on February 25, 2013. During the meeting the two sides Afghanistan issue held in Moscow,together with Russian exchange views on high-level interactions between the two Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Indian countries, economic and trade cooperation and issues of National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon on February common concern. 20, 2013. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr.Wei Wei and other VIP Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei and Indian guests are having a group picture with actors at the 2013 Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch enjoy Happy Spring Festival organized by the Chinese Embassy “China in the Spring Festival” exhibition at the 2013 Happy and FICCI in New Delhi on February 25,2013. Artists from Spring Festival. The exhibition introduces cultures, Jilin Province, China and Punjab Pradesh, India are warmly customs and traditions of Chinese Spring Festival. welcomed by the audience. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei(third from left) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei visits the participates in the “Happy New Year “ party organized by Chinese Visa Application Service Centre based in the Chinese Language Department of Jawaharlal Nehru Southern Delhi on March 6, 2013. -

Yining Li Influence of Ethical Factors on Economy

China Academic Library Yining Li Beyond Market and Government In uence of Ethical Factors on Economy China Academic Library Academic Advisory Board: Researcher Geng, Yunzhi, Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Professor Han, Zhen, Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Researcher Hao, Shiyuan, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Professor Li, Xueqin, Department of History, Tsinghua University, China Professor Li, Yining, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University, China Researcher Lu, Xueyi, Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Professor Tang, Yijie, Department of Philosophy, Peking University, China Professor Wong, Young-tsu, Department of History, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, USA Professor Yu, Keping, Central Compilation and Translation Bureau, China Professor Yue, Daiyun, Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Peking University, China Zhu, Yinghuang, China Daily Press, China Series Coordinators: Zitong Wu, Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, China Yan Li, Springer More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11562 Yining Li Beyond Market and Government Infl uence of Ethical Factors on Economy Yining Li Guanghua School of Management Peking University Beijing , China Sponsored by Chinese Fund for the Humanities and Social Sciences (ᵜҖ㧧ѝॾ⽮Պ、ᆖส䠁䍴ࣙ) ISSN 2195-1853 ISSN 2195-1861 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-662-44253-1 ISBN 978-3-662-44254-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-44254-8 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014944134 © Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Co., Ltd and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 This work is subject to copyright. -

Research on the Inter-Cultural Communication of Yanzhao Traditional Sports Culture Under the Background of the Winter Olympics

Advances in Physical Education, 2021, 11, 261-267 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ape ISSN Online: 2164-0408 ISSN Print: 2164-0386 Research on the Inter-Cultural Communication of Yanzhao Traditional Sports Culture under the Background of the Winter Olympics Huijian Wang1, Ying Huang1, Yi Yang1, Yalong Li2* 1College of Foreign Language Education and International Business, Baoding University, Baoding, China 2College of Physical Education, Baoding University, Baoding, China How to cite this paper: Wang, H. J., Abstract Huang, Y., Yang, Y., & Li, Y. L. (2021). Research on the Inter-Cultural Communi- Yanzhao Traditional Sports is an intangible cultural heritage with distinctive cation of Yanzhao Traditional Sports Cul- national characteristics. Taking advantage of the opportunity of the 2022 Bei- ture under the Background of the Winter jing-Zhangjiakou Winter Olympics, researching the inter-cultural communi- Olympics. Advances in Physical Education, 11, 261-267. cation of Yanzhao traditional sports and constructing an effective communi- https://doi.org/10.4236/ape.2021.112021 cation model will help grasp the initiative of the inter-cultural communica- tion of Yanzhao traditional sports culture and shape the image of Hebei. In Received: April 13, 2021 order to promote inter-cultural communication of Yanzhao traditional sports Accepted: May 16, 2021 Published: May 19, 2021 culture, it is advised to construct from improving the awareness of inter-cultural communication, selection of intercultural communication con- Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and tent, and broaden the channels of inter-cultural communication. Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Keywords License (CC BY 4.0). -

The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature : a Case Study of Howard Goldblatt's Translations of Mo Yan's Works

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Translation 3-9-2016 The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature : a case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works Yau Wun YIM Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Yim, Y. W. (2016). The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature: A case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd/16/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Translation at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS YIM YAU WUN MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS by YIM Yau Wun 嚴柔媛 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Translation LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 ABSTRACT The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature: A Case Study of Howard Goldblatt’s Translations of Mo Yan’s Works by YIM Yau Wun Master of Philosophy The purpose of this thesis is to explore the role of the translator and translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature through an illustration of the case of Howard Goldblatt’s translations of Mo Yan’s works. -

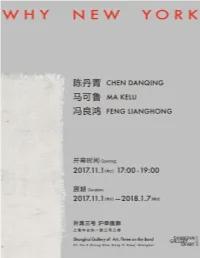

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

International Seminar on Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue

INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON SILK ROADS: ROADS OF DIALOGUE MALACCA, MALAYSIA 4th January 1991 Organized by: Ministry of Culture, Arts and Tourism, Malaysia National University of Malaysia Ministry of Education, Malaysia Chief Minister Department. Malacca With the Cooperation of: 1 Recent Studies in China on Admiral Zheng He's Navigation Liu Yingsheng Nanjing University, China At the end of 15th century great Portuguese sailor Vasco Da Gama returned to Europe from India. In the history of navigation, the Portuguese discovery is the very beginning of the new era. But before the Portuguese came to the east the Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean had already been a busy commercial region for a long time. Ships of China, Southeast Asia, Sub- continent, West Asia and East Africa had kept on coming and going from east to west and from west to east. Admiral Zheng He and his fleets’ navigation in the West Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean in the early 15th century is one of greatest achievements in the history of Chinese navigation activities. In the period from the 3rd year of Yong Le 永乐 (1405) to the 8th year of Xuan De 宣 德 (1433) Zheng He sailed 7 times to Southeast Asia and in the Indian Ocean. His fleet was the biggest in the world at that time. It consisted of more than 200 ships and more than 27,800 sailors and soldiers. The study on Zheng He's navigation activity was begun at the beginning of the Qing Dynasty when Zhang Tingyu 张廷玉 and his colleagues compiled the biography of Zheng He of the Ming Shi in the 17th century. -

Strategies for Sustainable Tourism at the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang, China

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN ARCHAEOLOGY ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT Martha Demas Neville Agnew Fan Jinshi Strategies for Sustainable Tourism at the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang, China 123 SpringerBriefs in Archaeology Archaeological Heritage Management Series Editors Douglas Comer Helaine Silverman Willem Willems More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10186 Martha Demas • Neville Agnew • Fan Jinshi Strategies for Sustainable Tourism at the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang, China With contributions by Shin Maekawa, Lorinda Wong, Wang Xudong, Su Bomin, Chen Ganquan, Wang Xiaowei, and Li Ping Martha Demas Neville Agnew Getty Conservation Institute Getty Conservation Institute Los Angeles , CA , USA Los Angeles , CA , USA Fan Jinshi Dunhuang Academy Dunhuang , China ISSN 1861-6623 ISSN 2192-4910 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-319-08999-7 ISBN 978-3-319-09000-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-09000-9 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014945549 © The J. Paul Getty Trust 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.