The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: an Interview'

An Interview with Zhang Hongtu 281 the roots - Chinese culture - had already become part of my life just as a tail is a part of a dog's body. I'm like a dog: the tail will be with me for 10 ever, no matter where I go. Sure, after nine years away from China, I forget many things, like I forget that when you buy lunch you have to pay Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: ration coupons with the money, and how much political pressure there An Interview' was in my everyday life. But because I still keep reading Chinese books and thinking about Chinese culture, and especially because I have the opportunity to see the differences between Chinese culture and the Western culture which I learned about after I left China, my image of Chinese culture has become more clear. Su Dongpo (the poet, I036- Zhang Hongtu was born in Gansu province, in northwest China, in lIOI) said: Bu shi Lushan zhen mianmu / Zhi yuan shen zai si shan I943, but grew up in Beijing. After studies at the Central Academy of zbong, Which means, one can't see the image of Mt. Lu because one is Arts and Crafts in Beijing, he was later assigned to work as a design inside the mountain. Now that I'm outside of the mountain, I can see supervisor in a jewellery company. In I982, he left China to pursue a what the image of the mountain is, so from this point of view I would say career as a painter in New York. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

Bol Shao Yung 20130225 Combined.Pdf (249.3Kb)

On Shao Yong’s Method for Observing Things The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bol, Peter. 2013. On Shao Yong’s Method for Observing Things. Monumenta Serica 61:287-299. Published Version http://www.monumenta-serica.de/monumenta-serica/publications/ journal/Catolog/Volume-LXI-2013.php Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17935880 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP On Shao Yong’s Method for Observing Things Peter K. Bol Charles H. Carswell Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, 2 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Title: 論邵雍之觀物法 Abstract: Shao Yong’s “Inner Chapters on Observing Things” develops a method for understanding the unity of heaven and man, tracing the decline of civilization from antiquity, and determining how the present can return to the ideal socio-political order of antiquity. Shao’s method is based on dividing any topic into fours aspects (for example, four Classics, four seasons, four kinds of rulers, etc.) and generating the systematic relations between these four member sets. Although Shao’s method was unusual at the time, the questions he was addressing were shared with mid-eleventh statecraft thinkers. 摘要:邵雍在《觀物內篇》中發展出了一種獨特的方法,用來理解天人合一、追溯三代以 後之衰、並確定如何才能復原三代理想的社會政治秩序。邵雍的方法立足於將任意一個主 題劃分為四個種類(例如,四種經典,四種季節,四種統治者,等等),並賦予這四個種 類之間以系統性的聯繫。雖然邵雍的方法在當時並非尋常,可是他所試圖解決的問題卻是 其他十一世紀中葉的政治制度思想家所共同思考的。 Shao’s claim to philosophical importance is based on a single book, the Huangji jingshi shu 皇極 經世書 (Supreme Principles for Governing the World) and the various charts and diagrams associated with it, and to much lesser extent his collection of poems, the Jirang ji 擊壤集. -

Summer 2020 Degrees Conferred

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Australia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Fofanah, Osman Ngunnawal 2913 Bachelor of Science in Education THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 1 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bangladesh Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Helal, Abdullah Al Dhaka 1217 Master of Science Alam, Md Shah Comilla 3510 Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 2 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bolivia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Arrueta Antequera, Lourdes Delta El Alto Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 3 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Brazil Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor dos Santos Marques, Ana Carolina Sao Jose Do Rio Pre 15015 Doctor of Philosophy Marotta Gudme, Erik Rio De Janeiro 22460 Bachelor of Science in Business Administration Magna Cum Laude Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Lucia Porto Alegre 90670 Doctor -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Rethinking Binarism in Translation Studies A Case Study of Translating the Chinese Nobel Laureates of Literature XIAO, DI How to cite: XIAO, DI (2017) Rethinking Binarism in Translation Studies A Case Study of Translating the Chinese Nobel Laureates of Literature, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12393/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 RETHINKING BINARISM IN TRANSLATION STUDIES A CASE STUDY OF TRANSLATING THE CHINESE NOBEL LAUREATES OF LITERATURE Submitted by Di Xiao School of Modern Languages and Cultures In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Durham University 2017 DECLARATION The candidate confirms that the work is her own and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. -

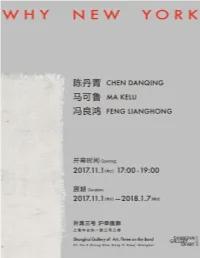

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

Warring States and Harmonized Nations: Tianxia Theory As a World Political Argument Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2020, 205 P

JYU DISSERTATIONS 247 Matti Puranen Warring States and Harmonized Nations Tianxia Theory as a World Political Argument JYU DISSERTATIONS 247 Matti Puranen Warring States and Harmonized Nations Tianxia Theory as a World Political Argument Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi heinäkuun 17. päivänä 2020 kello 9. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, on July 17, 2020 at 9 o’clock a.m.. JYVÄSKYLÄ 2020 Editors Olli-Pekka Moisio Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä Timo Hautala Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä Copyright © 2020, by University of Jyväskylä Permanent link to this publication: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-8218-8 ISBN 978-951-39-8218-8 (PDF) URN:ISBN:978-951-39-8218-8 ISSN 2489-9003 ABSTRACT Puranen, Matti Warring states and harmonized nations: Tianxia theory as a world political argument Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2020, 205 p. (JYU Dissertations ISSN 2489-9003; 247) ISBN 978-951-39-8218-8 The purpose of this study is to examine Chinese foreign policy by analyzing Chinese visions and arguments on the nature of world politics. The study focuses on Chinese academic discussions, which attempt to develop a ’Chinese theory of international politics’, and especially on the so called ’tianxia theory’ (天下论, tianxia lun), which is one of the most influential initiatives within these discussions. Tianxia theorists study imperial China’s traditional system of foreign relations and claim that the current international order, which is based on competing nation states, should be replaced with some kind of world government that would oversee the good of the whole planet. -

Gao Xingjian: Fiction and Forbidden Memory

China Perspectives 2010/2 | 2010 Gao Xingjian and the Role of Chinese Literature Today Gao Xingjian: Fiction and Forbidden Memory Zhang Yinde Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5269 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5269 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2010 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Zhang Yinde, « Gao Xingjian: Fiction and Forbidden Memory », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2010/2 | 2010, mis en ligne le 01 juin 2013, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ chinaperspectives/5269 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5269 © All rights reserved Special Feature s e Gao Xingjian: Fiction and v i a t c (1) n i Forbidden Memory e h p s c r YINDE ZHANG e p From Soul Mountain to One Man’s Bible , Gao Xingjian’s fiction is committed to a labour of transgressive remembering: excavating minority heritages eclipsed by the dominant culture, protecting individual memory from established historiography, and sounding the dark areas of personal memory, less to indulge in “repentance” than to examine identity. The writing of memory, thanks to fictionalisation, thus comes to resemble an exorcism that makes it possible to defy prohibitions by casting out external and internal demons and by imposing the existential prescription against normative judgement. n Gao Xingjian’s novel Soul Mountain , written between starting point for the present discussion. Inscribed as a ges - 1982 and 1989, there is a long description of an ancient ture against oblivion, its revelation denounces the violence of Imask. It is an anthropozoomorphic mask sculpted out of history, while also revealing an ambivalent fictional wood, no doubt dating back to the last Imperial Dynasty, approach. -

ABSTRACT SEARCHING for the CONSCIOUSNESS of THIRDNESS THROUGH GAO XINGJIAN's the OTHER SHORE and SIX WAYS of RUNNING by Jia

ABSTRACT SEARCHING FOR THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF THIRDNESS THROUGH GAO XINGJIAN’S THE OTHER SHORE AND SIX WAYS OF RUNNING by Jia-Yun Zhuang This creative thesis includes an introduction of the “Gao Xingjian Effect,” a review on the major themes in his work, and theoretical research on diasporic consciousness embedded in his work The Other Shore. The thesis also presents a full-length play – Six Ways of Running which was written under the influence and conception of Gao’s work, and a summary on the playwriting process and production reception of Six Ways of Running. The whole creative process focuses on the theme of interaction and confrontation between the individual and the collective and aims at exploring new possibilities beyond binary configuration. SEARCHING FOR THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF THIRDNESS THROUGH GAO XINGJIAN’S THE OTHER SHORE AND SIX WAYS OF RUNNING A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Theatre by Jia-Yun Zhuang Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2004 Advisor ________________________ Dr. Ann Elizabeth Armstrong Reader _________________________ Dr. Howard A. Blanning Reader _________________________ Dr. LuMing R. Mao TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page...................................................................................................... ............. i Table of Contents....................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgments..................................................................................................... -

Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik Versus the So-Called Tributary System

realpolitik versus tributary system armin selbitschka Early Chinese Diplomacy: Realpolitik versus the So-called Tributary System SETTING THE STAGE: THE TRIBUTARY SYSTEM AND EARLY CHINESE DIPLOMACY hen dealing with early-imperial diplomacy in China, it is still next W to impossible to escape the concept of the so-called “tributary system,” a term coined in 1941 by John K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng in their article “On the Ch’ing Tributary System.”1 One year later, John Fairbank elaborated on the subject in the much shorter paper “Tribu- tary Trade and China’s Relations with the West.”2 Although only the second work touches briefly upon China’s early dealings with foreign entities, both studies proved to be highly influential for Yü Ying-shih’s Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations published twenty-six years later.3 In particular the phrasing of the latter two titles suffices to demonstrate the three au- thors’ main points: foreigners were primarily motivated by economic I am grateful to Michael Loewe, Hans van Ess, Maria Khayutina, Kathrin Messing, John Kiesch nick, Howard L. Goodman, and two anonymous Asia Major reviewers for valuable suggestions to improve earlier drafts of this paper. Any remaining mistakes are, of course, my own responsibility. 1 J. K. Fairbank and S. Y. Teng, “On the Ch’ing Tributary System,” H JAS 6.2 (1941), pp. 135–246. 2 J. K. Fairbank in FEQ 1.2 (1942), pp. 129–49. 3 Yü Ying-shih, Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-barbarian Economic Relations (Berkeley and Los Angeles: U. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Innovation Und Wandel Durch Chinas Heimgekehrte Akademiker?

Reverse Brain Drain: Innovation und Wandel durch Chinas heimgekehrte Akademiker? Eine Studie zum Einfluss geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlicher Rückkehrer am Beispiel chinesischer Eliteuniversitäten Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg im Promotionsfach Sinologie vorgelegt von Birte Klemm Hamburg, 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda Datum der Disputation: 14. August 2018 游学, 明时势,长志气,扩见闻,增才智, 非游历外国不为功也. 张之洞 1898 年《劝学篇·序》 Danksagung Ohne die Unterstützung einer Vielzahl von Menschen wäre diese Dissertation nicht zustande ge- kommen. Mein besonderer Dank gilt dem Betreuer dieser Arbeit, Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich, für seine große Hilfe bei den empirischen Untersuchungen und die wertvollen Ratschläge bei der Erstellung der Arbeit. Für die Zweitbegutachtung möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei Frau Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda bedanken. In der Konzeptionsphase des Projekts haben mich meine ehemaligen Kolleginnen und Kollegen am GIGA Institut für Asien-Studien, vor allem Prof. Dr. Thomas Kern, mit fachkundigen Ge- sprächen unterstützt. Ein großes Dankeschön geht überdies an Prof. Dr. Wang Weijiang und seine ganze Familie, an Prof. Dr. Chen Hongjie, Prof. Dr. Zhan Ru und Prof. Dr. Shen Wenzhong, die mir während meiner empirischen Datenerhebungen in Peking und Shanghai mit überwältigender Gastfreundschaft und Expertise tatkräftig zur Seite standen und viele Türen öffneten. An dieser Stelle möchte ich auch die zahlreichen Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmern der empiri- schen Umfragen dieser Studie würdigen. Hervorheben möchte ich die Studierenden der Beida und Fudan, die mir sehr bei der Verteilung der Fragebögen halfen und mir vielfältige Einblicke in das chinesische Hochschulwesen sowie studentische und universitäre Leben ermöglichten.