Art and China's Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

Art Market Trends Tendances Du Marché De L'art

Art market trends Tendances du marché de l'art THE WORLD LEADER IN ART MARKET INFORMATION Art market trends Tendances du marché de l'art 2005 $ 4.15 billion (€ 3.38 billion) 3.38 (€ billion 4.15 $ worldwide: auctions Art Fine at Turnover offer. on lots 320,000 of volume stable practically billion, vs. 3.6 $ billion the previous year, In despite 2005 the a turnover for record-breaking! Fine are gures Art sales fi The exceeded 4 $ well. so performed never has market art international The a million dollars, compared with compared in only 393 2004 dollars, a and million than more for hammer the under went lots 477 than less into of a rise sales 1 multiplication $ exceeding No million 19% the from translated ation on in recorded infl 2004. price This following already year, last 10.4%* of increase came on the of back a progression price incredible This Tendances du marché de l'art de marché du Tendances Art market trends trends market Art Artprice Global Index: Paris - New York - London (1994 - 2005) Base January 1994 = 100 - Quarterly data Artprice Indices are calculated with the Repeated Sales method (Econometric calculations on sales/resales of similar works) 10 000 $, 10 et 56% en deçà de 000 $.2 Ce segment est en 2005 en publiques ventes ont adjugés été moins de cette cette année, faisant suite aux d’affaires 19% mondial, de une hausse élévation déjà des A prix l’origine de de cette 10,4% incroyable progression du chiffre (3,38 d’euro) dollars de milliards milliards 4,15 : mondiales enchères Artaux Fine de ventes des Produit présentés. -

Rodney Graham CV

Rodney Graham Lives and works in Vancouver, Canada 1979–80 Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada 1968–71 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 1949 Born in Vancouver, Canada Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 ‘Artists and Models', Serlachius Museum Gösta, Mänttä, Finland ‘Painting Problems’, Lisson Gallery 2019 303 Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2018 ‘Central Questions of Philosophy’, Lisson Gallery, London, UK 2017 ‘Lightboxes’, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany 303 Gallery, New York, NY, USA ‘That’s Not Me’, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK; Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland ‘Canadian Impressionist’, Canada House, London, UK ‘Media Studies’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland 2016 ‘You should be an Artist’, Le Consortium, Dijon, France ‘Waterloo Billboard Commissions’, Hayward Gallery, London, UK ‘Jack of All Trades’, Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art, Toronto, Canada ‘Più Arte dello Scovolino!’, Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy Alt Art Space, Istanbul Turkey 2015 Sammlung Goetz, Munich, Germany ‘Kitchen Magic Drawings’, Galerie Rüdinger Schöttle, Munich, Germany 2014 ‘Rodney Graham: Props and Other Paintings’, Charles H. Scott Gallery, Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver, Canada ‘Collected Works’, Rennie Collection, Vancouver, Canada ‘Torqued Chandelier Release and Other Works’, Belkin Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 2013 Lisson Gallery, London, UK 303 Gallery, New York, NY, USA ‘The Four Seasons’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland 2012 ‘Canadian Humourist’, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada Johnen Galerie, Berlin, Germany 2011 Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, IL, USA ‘Vignettes of Life’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland ‘Rollenbilder – Rollenspiele’, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, Austria ‘The Voyage or Three Years at Sea: Part 1. -

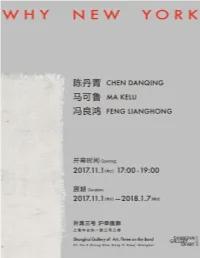

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 Winter 2021

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 winter 2021 Journal of the school of arts and humanities and the edith o'donnell institute of art history at the university of texas at dallas Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 185 11/6/20 1:24 PM 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM 1 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 1 11/6/20 1:23 PM This issue of Athenaeum Review is made possible by a generous gift from Karen and Howard Weiner in memory of Richard R. Brettell. 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM Athenaeum Review Athenaeum Review publishes essays, reviews, Issue 5 and interviews by leading scholars in the arts and Winter 2021 humanities. Devoting serious critical attention to the arts in Dallas and Fort Worth, we also consider books and ideas of national and international significance. Editorial Board Nils Roemer, Interim Dean of the School of Athenaeum Review is a publication of the School of Arts Arts and Humanities, Director of the Ackerman and Humanities and the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Center for Holocaust Studies and Stan and Art History at the University of Texas at Dallas. Barbara Rabin Professor in Holocaust Studies School of Arts and Humanities Dennis M. Kratz, Senior Associate Provost, Founding The University of Texas at Dallas Director of the Center for Asian Studies, and Ignacy 800 West Campbell Rd. JO 31 and Celia Rockover Professor of the Humanities Richardson, TX 75080-3021 Michael Thomas, Director of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History and Edith O’Donnell [email protected] Distinguished University Chair in Art History athenaeumreview.org Richard R. -

Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza

PLACE UNDER THE LINE PLACE UNDER THE LINE : july / august 1 vol.9 no. 4 J U L Y / A U G U S T 2 0 1 0 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4 INSIDE New Art in Guangzhou Reviews from London, Beijing, and San Artist Features: Gu Francisco Wenda, Lin Fengmian, Zhang Huan The Contemporary Art Academy of China Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4, JULY/AUGUST 2010 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 33 4 Contributors 6 The Guangzhou Art Scene: Today and Tomorrow Biljana Ciric 15 On Observation Society Anthony Yung Tsz Kin 20 A Conversation with Hu Xiangqian 46 Biljana Ciric, Li Mu, and Tang Dixin 33 An interview with Gu Wenda Claire Huot 43 China Park Gu Wenda 46 Cubism Revisited: The Late Work of Lin Fengmian Tianyue Jiang 63 63 The Cult of Origin: Identity Politics and Cultural Capital in Contemporary Chinese Art J. P. Park 73 Zhang Huan: Paradise Regained Benjamin Genocchio 84 Contemporary Art Academy of China: An Introduction Christina Yu 87 87 Of Jungle—In Praise of Distance: Reflections on Anonymity and Contemporaneity in Chinese Art Beatrice Leanza 97 Shanghai: Art of the City Micki McCoy 104 Zhang Enli Natasha Degan 97 111 Chinese Name Index Cover: Zhang Huan, Hehe Xiexie (detail), 2010, mirror-finished stainless steel, 600 x 420 x 390 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Vol.9 No.4 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art president Katy Hsiu-chih Chien legal counsel Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C.C. -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

To Care, to Curate. a Relational Ethic of Care

Curare: to care, to curate. A relational ethic of care in curatorial practice Sibyl Annice Fisher Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies November, 2013 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. © 2013 The University of Leeds and Sibyl Annice Fisher The right of Sibyl Annice Fisher to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Readers are respectfully advised that this document contains the names and images of Indigenous persons who are now deceased. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies for the international scholarship that enabled me to undertake this research project, and David Jackson for the initial conversation. For archival assistance, many thanks to Gary Haines at Whitechapel Art Gallery, Jennifer Page at the Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Janet Moore at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, and Gary Dufour at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Thanks also to Aunty Stephanie Gollan at Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute. Thank you to Rayma Johnson for kind permission to use the image of Russell Page, and to Glen Menzies and Hetti Perkins for advice on reproducing work by Emily Kame Kngwarreye. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02450-2 — Art and Artists in China Since 1949 Ying Yi , in Collaboration with Xiaobing Tang Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02450-2 — Art and Artists in China since 1949 Ying Yi , In collaboration with Xiaobing Tang Index More Information Index Note: The artworks illustrated in this book are oil paintings unless otherwise stated. Figures 1–33 will be found in Plate section 1 (between pp. 49 and 72); Figures 34–62 in section 2 (between pp. 113 and 136); Figures 63–103 in section 3 (between pp. 199 and 238); Figures 104–161 in section 4 (between pp. 295 and 350). abstract art (Chinese) 163, 269–274, art market see commercialization of art 279 art publications (new) 86, 165–172 early 1980s 269–271 Artillery of the October Revolution 42 ’85 Movement –“China/Avant-Garde” Arts and Craft Movement 268 269–271 Attacking the Headquarters (Fig. 27) 1989 – present (post-modern) stage 273 avant-garde art (Chinese) 141, 146, 169, conceptual abstraction 273–274, 277–278 176, 181, 239, 245, 258, 264–265 expressive abstraction 273–274, 276 see also “China/Avant-Garde” material abstraction 277 exhibition schematic abstraction 245, 274 avant-garde art (Russian) 3–4 abstract art (Western) 147–148, 195–196, avant-garde art (Western) 100, 101, 267–268 see also Abstract 255–256, 257, 264 see also Modernism Expressionism; Hard-Edge / Structural Abstraction Bacon, Francis 243 Abstract Expressionism 256, 269, 274 Bao Jianfei 172 academic realism 245, 270 New Space No.1 167 academies see art academies Barbizon School 87 Ai Xinzhong 14 Bauhaus School 269 Ai Zhongxin 5 Beckmann, Max 246 amateur art/artists 35, 74–75, 106–108, Bei Dao 140 137–138, 141, -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York.