Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

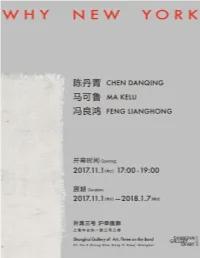

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Innovation Und Wandel Durch Chinas Heimgekehrte Akademiker?

Reverse Brain Drain: Innovation und Wandel durch Chinas heimgekehrte Akademiker? Eine Studie zum Einfluss geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlicher Rückkehrer am Beispiel chinesischer Eliteuniversitäten Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg im Promotionsfach Sinologie vorgelegt von Birte Klemm Hamburg, 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda Datum der Disputation: 14. August 2018 游学, 明时势,长志气,扩见闻,增才智, 非游历外国不为功也. 张之洞 1898 年《劝学篇·序》 Danksagung Ohne die Unterstützung einer Vielzahl von Menschen wäre diese Dissertation nicht zustande ge- kommen. Mein besonderer Dank gilt dem Betreuer dieser Arbeit, Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich, für seine große Hilfe bei den empirischen Untersuchungen und die wertvollen Ratschläge bei der Erstellung der Arbeit. Für die Zweitbegutachtung möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei Frau Prof. Dr. Yvonne Schulz Zinda bedanken. In der Konzeptionsphase des Projekts haben mich meine ehemaligen Kolleginnen und Kollegen am GIGA Institut für Asien-Studien, vor allem Prof. Dr. Thomas Kern, mit fachkundigen Ge- sprächen unterstützt. Ein großes Dankeschön geht überdies an Prof. Dr. Wang Weijiang und seine ganze Familie, an Prof. Dr. Chen Hongjie, Prof. Dr. Zhan Ru und Prof. Dr. Shen Wenzhong, die mir während meiner empirischen Datenerhebungen in Peking und Shanghai mit überwältigender Gastfreundschaft und Expertise tatkräftig zur Seite standen und viele Türen öffneten. An dieser Stelle möchte ich auch die zahlreichen Teilnehmerinnen und Teilnehmern der empiri- schen Umfragen dieser Studie würdigen. Hervorheben möchte ich die Studierenden der Beida und Fudan, die mir sehr bei der Verteilung der Fragebögen halfen und mir vielfältige Einblicke in das chinesische Hochschulwesen sowie studentische und universitäre Leben ermöglichten. -

Artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers Global Chinese Antiques and Art Auction Market B Annual Statistical Report: 2012

GLOBAL CHINESE ANTIQUES AND ART AUCTION MARKET ANNUAL STATISTICAL REPORT 2012 artnet and the China Association of Auctioneers Global Chinese Antiques and Art Auction Market B Annual Statistical Report: 2012 Table of Contents ©2013 Artnet Worldwide Corporation. ©China Association of Auctioneers. All rights reserved. Letter from the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) President ........... i About the China Association of Auctioneers (CAA) ................................. ii Letter from the artnet CEO .................................................................. iii About artnet ...................................................................................... iv 1. Market Overview ............................................................................. v 1.1 Industry Scale ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Market Scale ............................................................................. 3 1.3 Market Share ............................................................................. 5 2. Lot Composition and Price Distribution ........................................ 9 2.1 Lot Composition ....................................................................... 10 2.2 Price Distribution ...................................................................... 21 2.3 Average Auction Prices ............................................................. 24 2.4 High-Priced Lots ....................................................................... 27 3. Regional Analysis -

Art and China's Revolution

: january / february 9 January/February 2009 | Volume 8, Number 1 Inside Special Feature: The Phenomenon of Asian Biennials and Triennials Artist Features: Yang Shaobin, Li Yifan Art and the Cultural Revolution US$12.00 NT$350.00 6 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2009 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 32 4 Contributors Autumn 2008 Asian Biennials 6 Premature Farewell and Recycled Urbanism: Guangzhou Triennial and Shanghai Biennale in 2008 Hilary Tsiu 16 Post-West: Guangzhou Triennial, Taipei Biennial, and Singapore Biennale Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker Contemporary Asian Art and the Phenomenon of the Biennial 30 Introduction 54 Elsa Hsiang-chun Chen 32 Biennials and the Circulation of Contemporary Asian Art John Clark 41 Periodical Exhibitions in China: Diversity of Motivation and Format Britta Erickson 47 Who’s Speaking? Who’s Listening? The Post-colonial and the Transnational in Contestation and the Strategies of the Taipei Biennial and the Beijing International Art Biennale Kao Chien-hui 54 Contradictions, Violence, and Multiplicity in the Globalization of Culture: The Gwangju Biennale 78 Sohl Lee 61 The Imagined Trans-Asian Community and the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale Elsa Hsiang-chun Chen Artist Features 67 Excerpts fom Yang Shaobin’s Notebook: A Textual Interpretation of X-Blind Spot Long March Writing Group 78 Li Yifan: From Social Archives to Social Project Bao Dong Art During the Cultural Revolution 94 84 Art and China’s Revolution Barbara Pollack 88 Zheng Shengtian and Hank Bull in Conversation about the Exhibition Art and China’s Revolution, Asia Society, New York 94 Red, Smooth, and Ethnically Unified: Ethnic Minorities in Propaganda Posters of the People’s Republic of China Micki McCoy Reviews 101 Chen Jiagang: The Great Third Front Jonathan Goodman 106 AAA Project: Review of A-Z, 26 Locations to Put Everything 101 Melissa Lam 109 Chinese Name Index Yuan Goang-Ming, Floating, 2000, single-channel video, 3 mins. -

James Cox Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JAMES COX Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:10 Nov 2009 Duration: about 1 hr 27 mins Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): I would love for you to talk a little bit about Grand Central Gallery, what it represented, whom it represented, your impressions about the exhibition, and how relationships were developed. You can tell any stories you want to tell. To begin, can you talk a little bit about Grand Central Gallery, how it was positioned and how you came upon these artists? James Cox (JC): I came to New York in 1976, and the reason my wife and I came was that I got a job, which is always a wonderful opportunity. I was 30 years old. I met my wife in Oklahoma City when we were in college together. Her father was an artist who showed in Chicago, New York, and Santa Fe. The New York gallery that represented him was the Grand Central Gallery. He was very familiar with the staff but more importantly he was familiar with the first Director of Grand Central Galley, who founded the gallery in 1922. He had been director for 56 years and was ready to retire. My father-in-law kept saying, ‘You really ought to go to New York and get in touch with the board; let them know that you are available…’, and so on. So I did that. I was very lucky to be hired. In brief, the gallery was set up to showcase American art, and was backed up by prominent American businessman including very major names in business, banking, and law. -

China As an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20Th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni

China as an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni 1 China as an Issue is an ongoing lecture series orga- nized by the Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum since 2018. Chinese scholars are invited to discuss topics related to China or the world, as well as foreign schol- ars to speak about China or international questions in- volving the subject of China. Through rigorous scruti- nization of a specific issue we try to avoid making generalizations as well as the parochial tendency to reject extraterritorial or foreign theories in the study of domestic issues. The attempt made here is not only to see the world from a local Chinese perspective, but also to observe China from a global perspective. By calling into question the underlying typology of the inside and the outside we consider China as an issue requiring discussion, rather than already having an es- tablished premise. By inviting fellow thinkers from a wide range of disciplines to discuss these topics we were able to negotiate and push the parameters of art and stimulate a discourse that intersects the arts with other discursive fields. The idea to publish the first volume of China as An Issue was initiated before the rampage of the coron- avirus pandemic. When the virus was prefixed with “China,” we also had doubts about such self-titling of ours. However, after some struggles and considera- tion, we have increasingly found the importance of 2 discussing specific viewpoints and of clarifying and discerning the specific historical, social, cultural and political situations the narrator is in and how this helps us avoid discussions that lack direction or substance. -

蔡 佳 葳 Charwei Tsai Born 1980 Bonsai Series III – No

蔡 佳 葳 Charwei Tsai Born 1980 Bonsai Series III – no. VII, 2011 black ink on lithographs, 26 x 31 cm 蔡 佳 葳 DISCUSSION 1 The artist has created lithographic prints of Bonsai trees. Can you see what the artist has Charwei Tsai included on the tree in place of leaves? Born 1980 2. The words are the lyrics of love songs by the sixth Dalai Lama. Why do you think the artist Bonsai Series III – no. VII, 2011 chose to depict the Bonsai trees with these lyrics? CONTEMPORARY ART FROM MAINLAND CHINA, TAIWAN AND HONG KONG black ink on lithographs, 26 x 31 cm 3 Do you think the work has a spiritual, philosophical or religious connotation? Why? ABOUT THE ARTIST 4. How did the artist give the work a sense of time and also of movement? Charwei Tsai explores spiritual and environmental Born in Taiwan, Charwei was educated overseas, and she 5. The colour palette of the work is minimal. Why do you think Charwei decided to do this? themes through a variety of media including videos, currently lives between Taipei, Taiwan and What mood or feeling do you think it gives the work? photographs, installation and performance based works. Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. She is fascinated by Charwei often uses calligraphy to explore Buddhist concepts of impermanence and emptiness, which are texts on a range of natural surfaces such as tofu, tree central to Buddhist belief, and which the artist defines ACTIVITIES trunks, mushrooms and ice. Through a detailed and as an ‘understanding of the interdependence between Thinking repetitive process she reaches a meditative state. -

Chinas Ausbildungs- Und Hochschul- System Unter Reformdruck 11

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. VOLKSREPUBLIK CHINA Masse statt Klasse? DR. PETER HEFELE BERNHARD REIFELD* JANINA STURM* Chinas Ausbildungs- und Hochschul- system unter Reformdruck 11. Dezember 2012 Die konfuzianisch geprägte Wertschätzung Meilenstein war 1999 dann der „Action Plan for www.kas.de/china von Bildung ist auch im modernen China un- Educational Vitalization Facing the 21st Century“. gebrochen. Zugleich fragen sich Eltern, Schü- Dieser sah vor, China durch eine verbesserte Bil- ler und Arbeitgeber, ob das bestehende Aus- dung insbesondere in Naturwissenschaften und bildungs- und Hochschulsystem noch an- Technologie so zu stärken, dass es im 21. Jahr- gemessen ausbildet, um vor dem Hinter- hundert auch im Bildungsbereich international grund eines enormen gesellschaftlichen und wettbewerbsfähig sein würde. wirtschaftlichen Strukturwandels bestehen zu können. Was sind die Ursachen für die Kri- Der politisch forcierte Strukturwandel der chinesi- tik am bestehenden Bildungswesen? Welche schen Volkswirtschaft bildet den entscheidenden Reformansätze gibt es? Welche Rolle spielt Hintergrund der aktuellen bildungspolitischen Dis- China für den internationalen Bildungsmarkt? kussionen2. Soll der Übergang von der „Weltfab- rik“, von „made in China“ zu „designed in China“ Die ersten Ansätze eines modernen Bildungssys- gelingen, so liegt der Engpass hauptsächlich im tems bildeten sich in China erst seit 1978 wieder Bereich ausreichend qualifizierter Humanressour- heraus. Davor war es in der Volksrepublik zu ei- cen. Zwar stehen -

2004 V03 03 Wu H P005.Pdf

: Figure 1. Marc Riboud, A Student in the Central Academy of Fine Arts Making an Image of Mao Zedong, 1957, black-and-white photography. Courtesy of Chambers Fine Art The exhibition Intersection,presented at Chambers Fine Art in New York City in June 2004, deals with a fundamental issue in contemporary Chinese art: the interrelationship between photography and painting. It is fundamental because few oil painters and photographers in post-Cultural Revolution China can escape this interrelationship which has influenced and even controlled their art in different ways and on multiple levels. From the 1960s through the 1980s, photography provided painting with a state sanctioned reality to depict (although the content of this reality changed greatly over time), while most “experimental photographers” (shiyan sheyingjia) that emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s were first trained as painters or graphic artists. How do painting and photography interact with each other in today’s Chinese art? To Chen Danqing, one of the six artists featured in this exhibition, “copying [photographs in oil] is not to imitate other people’s language. Like playing musical compositions, copying is itself a language.”The other five artists each answer the question differently; but all have problematized the painting/photography relationship in their works. By doing so, these artists—three photographers and three oil painters—demonstrate how this relationship has become a shared focus of their artistic experi- mentation. To understand the experimental nature of their works, however, we need to briefly reflect upon the connections between painting and photography in Chinese art since the 1960s. *** “Painting from photographs” became a legitimate artistic practice during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when numerous paintings—portraits of Mao Zedong and his wife Jiang Qing, heroic images of the revolutionary masses, and narrative pictures of the Party’s glorious history—were Figure 2.